Edwin Tanner: A Selection of Paintings and Prints from the Estate

Victoria Perin

Edwin Tanner was the most insider of outsider artists. Which is to say that the art world immediately saw that he was more interesting than them—guided by more powerful passions—and they welcomed him into the fold, hoping to glean some vitality from his presence. Trained at evening classes in Hobart from the age of thirty and working as a full-time artist by the age of forty-five, Tanner was an outsider artist only in that, when other artists spoke about him, they found it necessary to refer to him as “an engineer.”

There are some artists whose profession you need to know before you understand them, and art history has decided that you need to know that Tanner was an engineer. Not to refute, but rather to intensify this, Charles Nodrum Gallery also wants you to know that he occupied himself not only with “engineering (his dual profession),” but also,

“mathematics (it’s said that, at sixteen, he completed a four-year London University course in higher mathematics in four months), philosophy (which he read and studied extensively), poetry (he was a published poet and also wrote short stories), cycling (as a teenager, he was a competitive cyclist and designed and built his own bicycle), flying (he was involved with aircraft design during the Second World War and was later an amateur pilot)—and more.”

You need to know, in other words, that he was an interesting guy, whose activity demonstrates that, somehow, he managed to access all parts of his human soul.

Tanner was “discovered” in Melbourne after submitting work for the newly revived Contemporary Art Society Exhibition in 1954. He’d never had a solo exhibition, and had only been in three other society group hangs, but the National Gallery of Victoria bought his major painting The Public Servant (1953), of which there is a study in the present exhibition. As Barrett Reid effused, he appeared, at age thirty-four, to be “fully formed, austere and, original,” his audience suffering “no lacunae, half-formed fledglings, (or) juvenilia.”

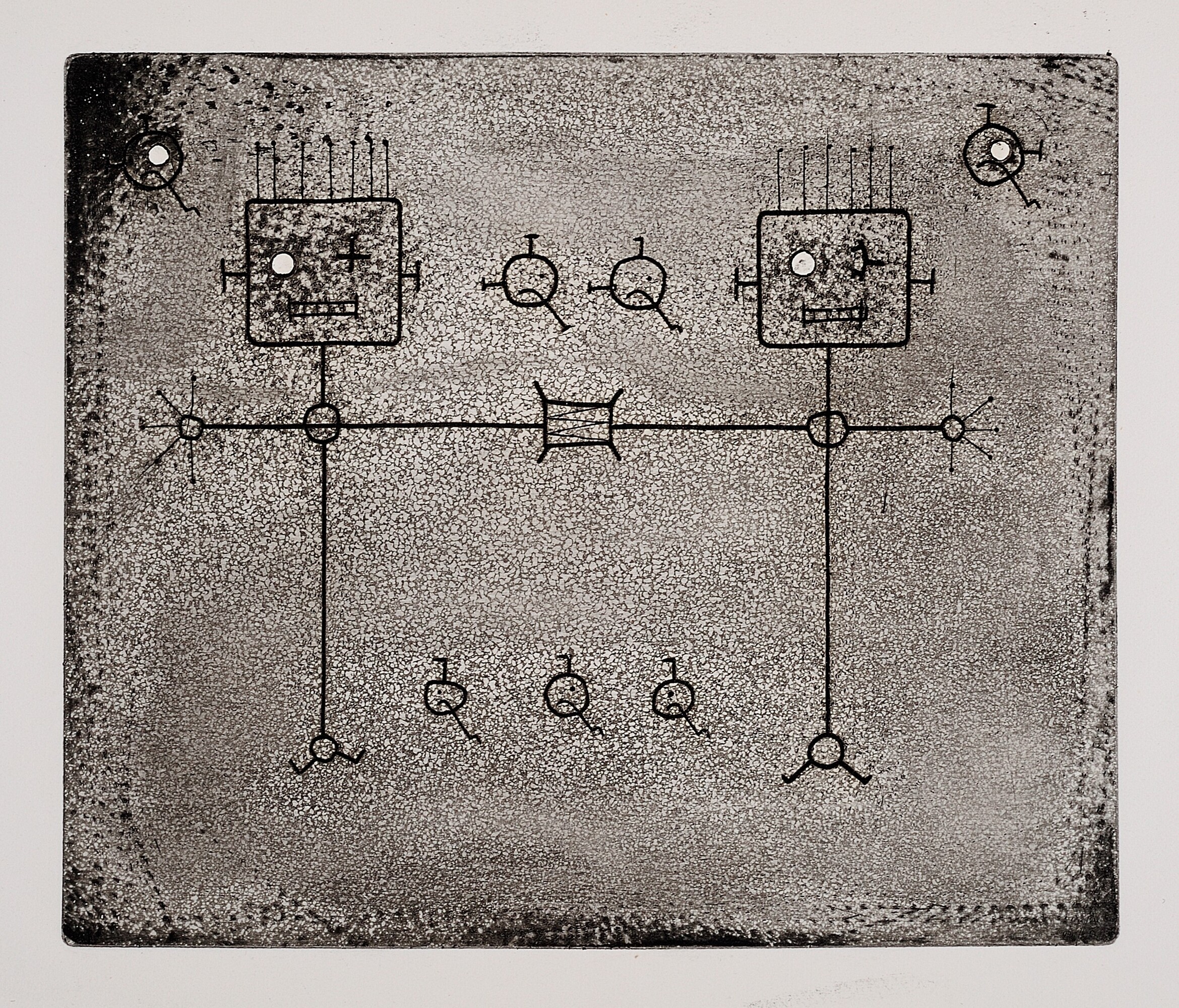

In fact, it was a few years before Tanner would actually mature into his signature style, but the elements are all present in ‘Study for The Public Servant’ (1953). Tanner’s classic style has an airless humour, a vacuum-packed comical abstraction. His early work is dressed lightly in social commentary. (Undoubtedly the reason the NGV bought a work by an untested talent was for the clean cut it made into middleclass self-esteem. “I am a public servant,” defended the Director of the NGV at the time “and I don’t object to it.”) Through the rest of the 1950s and into the 1960s, as a precursor to computer art, Tanner developed a memorable style I think of as “circuit-board abstraction,” which expanded elegant observations about electronic elements into a universalism that suggests the connection, order and, balance of existence.

While his disappearing, electrified line caused reviewers to constantly mention Paul Klee, there are more obvious and local relatives for Tanner’s near mystic lawfulness. As Kevin Murray writes, “passing through this door also would be Melbourne figures such as Gerald Murnane, people who prefer, as Borges wrote of Valery, ‘the lucid pleasures of thought and the secret adventures of order.’”

In one painting on display his appreciation of Elwyn Lynn is clear; his version of colour-field painting suggests that he was affected by The Field exhibition in 1968; and his best work demonstrates that he was a bedfellow of Robert Klippel and John Brack (as many people have said). This last reference is due for an update, as we might now say his sensibility is overall more in-line with Helen Maudsley’s. Sitting somewhere between this formidable artist couple, Tanner appears a platonic third.

Charles Nodrum Gallery has promoted Tanner’s spindly abstraction since 1988. I was interested in reviewing this exhibition and not, say, his 2018 retrospective at the TarraWarra Museum of Art, because of their claim that this exhibition offers “two facets of the artist’s work that we’ve not yet exhibited at the gallery.” Why the hold out? I sensed that the two facets would somewhat muddy the vision of the artist that a gallerist might otherwise want to keep straight. But it’s been thirty-five years! Let’s get weird, right? Nodrum promises “two works from the horoscope series––a suite of paintings of the signs of the Zodiac … and a group of etchings which the artist made at RMIT in the early 1960s.”

This RMIT print room was a social space, with at least a dozen other artists allowed to print out of school hours. Tanner had moved from Hobart to Melbourne in 1957, and (as quoted by Murray) to his “terrible disappointment” found “in the arts of all things, everything sewn up,” with other painters appearing to be “Neanderthals living in caves.” (In the digitised collection of the State Library of Victoria, I zoom in on a photograph of Tanner at an art opening. He is wearing a Welsh-Celtic conversation-piece tie and protectively gripping a paperback of War and Peace). A list of his artist friends is almost exclusively made up of artists connected to the print room. I imagine that the RMIT was one place that Tanner was able to connect with his Melbourne peers, if elsewhere he found networking difficult.

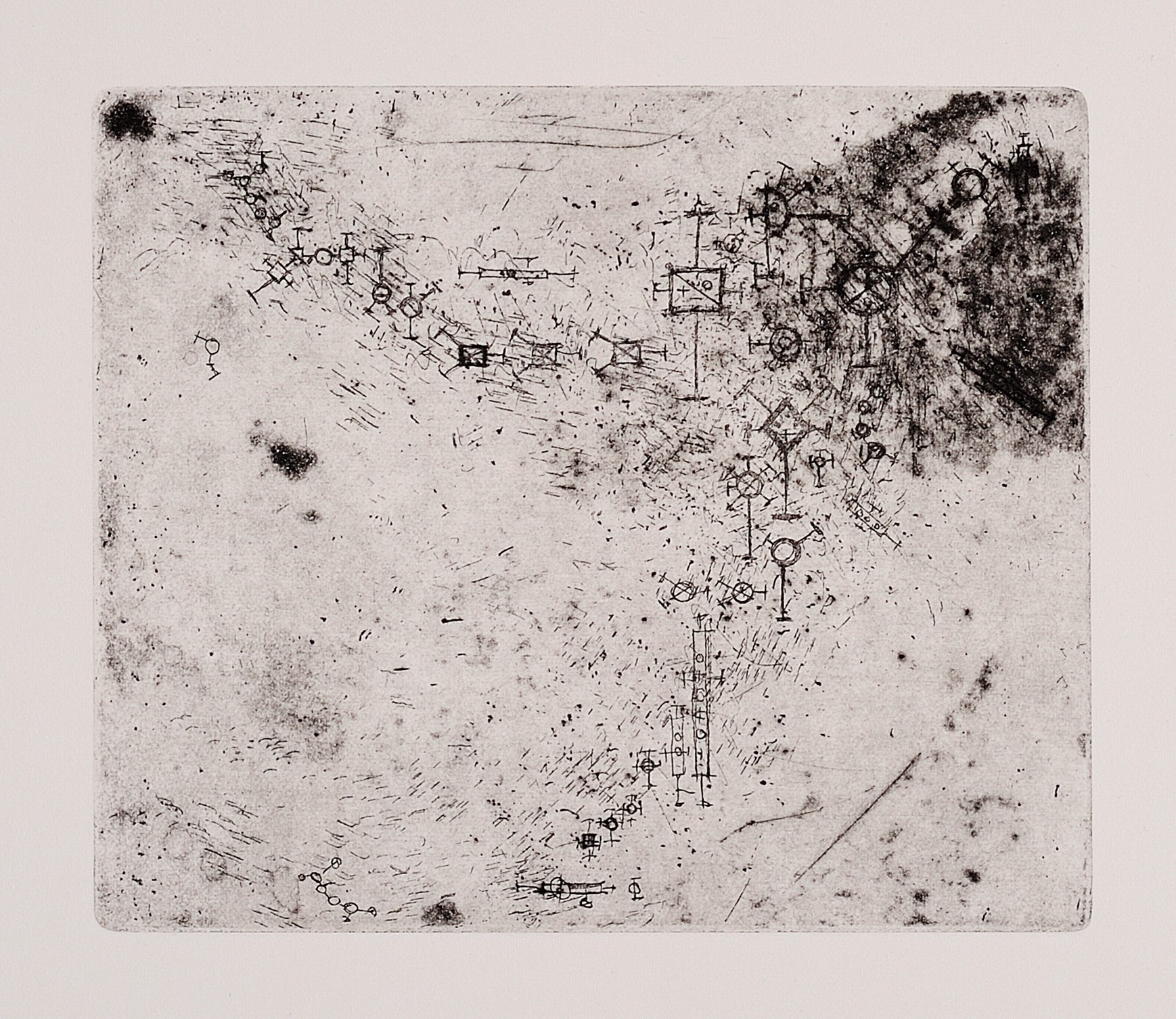

The etchings themselves I make short work of. I like them well enough, but then I like messy prints. I can picture Tanner at RMIT, experimenting with acid and leaving the workshop with a handful of incidentally corroded images. I wonder if the artist was pleased that his signature light line was over-written with the accidental hallmarks of amateur printing. I wonder if he was excited or confronted by the challenges of printmaking. I do have to add that I dislike whenever Tanner’s circuit elements grow faces, which appear to cavort together like Play School presenters. On close inspection, the prints from this period all have cute little winky faces somewhere.

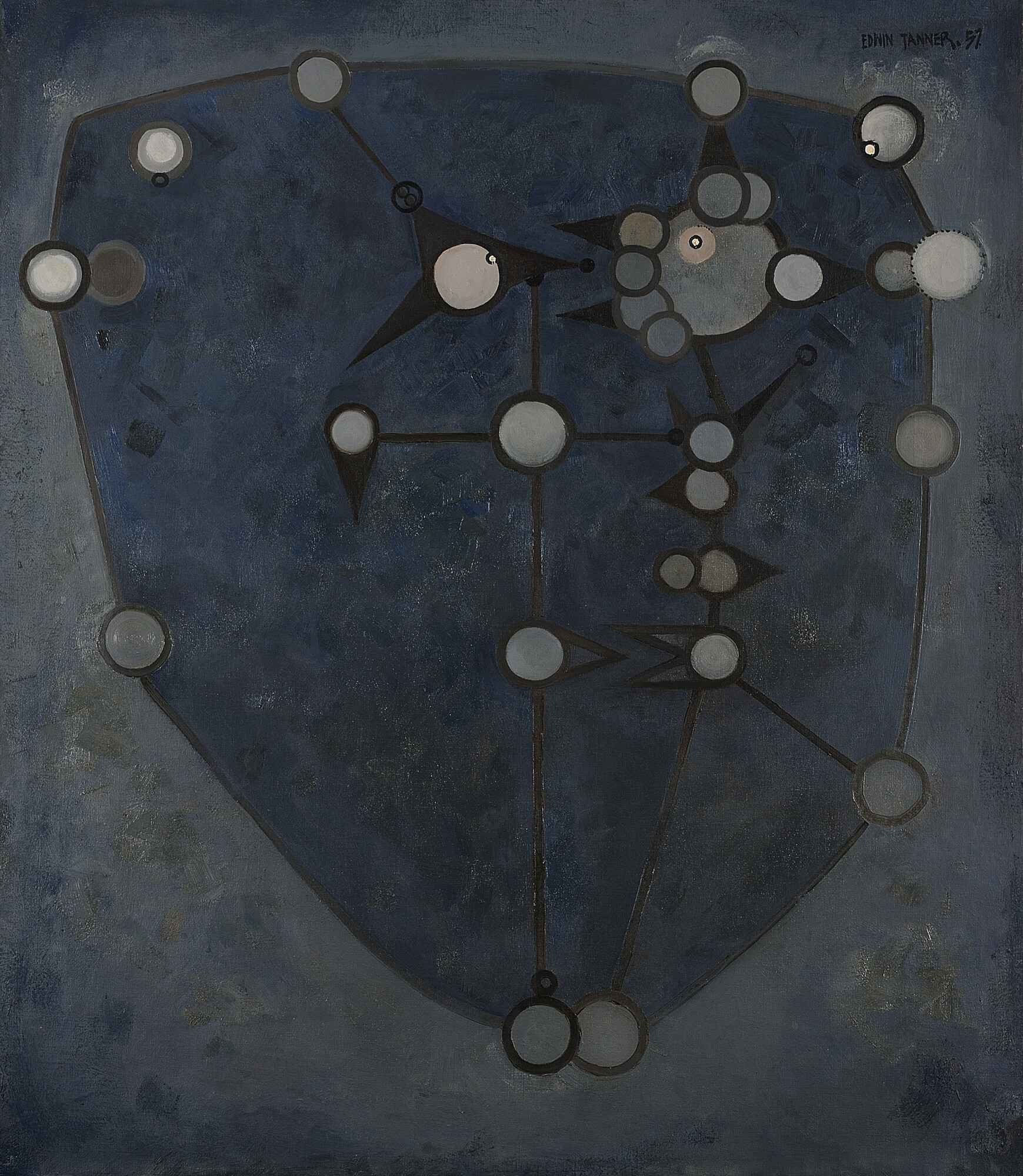

The promised horoscope series is more enticing. The moment I learnt that Tanner did horoscope paintings, I was keen. When I found out they were loose, gestural paintings, I was sold. How can the 1950s Tanner, who perceives the universe in a dun-coloured circuit board, be the same artist making sky-blue totems out of the zodiac symbols in 1971? A thrilling contradiction. I do not buy the suggestion (originally from Tanner’s biographer Jenepher Duncan) that the horoscope paintings were inspired by Pierre Soulages. Tanner did meet the French master of gestural abstraction in 1967, but was this chance meeting enough to forge a compelling influence? Nodrum’s uncatalogued inclusion of a work by Australian painter Peter Upward demonstrates the difference between a committed gestural abstractionist and a painter who is trying to loosen up for a change.

While the Horoscope series is from 1971, the inclusion in this exhibition of a wonderful 1957 painting Space Station Zebra, shows that Tanner was from the space-race generation. Nodrum notes that he “got pleasure from identifying satellites in the sky at night and distinguishing them from stars.” Space Station Zebra is more about this kind of forensic observation of space than it is about the celestial. But over a decade later Tanner would drop all reference to mapping, points of data and empirical charts, and turn his hand to the hidden influence of the zodiac.

The two horoscope paintings aren’t evenly matched. The painting Aquarius (c.1971) presents a horrible little illustration of the wiggly waves of that sign. In contrast, the painting Aries (1958-1971) is a mysterious delight. A ram’s head with curly horns and a perfect little halo. Barrett Reid was completely convinced, writing in the year of their creation that they might be Tanner’s “most beautiful works to date.” Reid saw no contradiction between old and new style, arguing that this was a full maturation, when “all precise linearity” was not abandoned, but rather present “in its absence.” Nodrum seems more hesitant, perhaps worried about the complexity of explaining how this “student of scientific method and Ludwig Wittgenstein” took a hard left into the Age of Aquarius.

There is some biographical information that may ease the paradox. Tanner died in 1980, and before he passed away his last decade seemed beset by existential crisis, accompanied by the continuation of acute and chronic pain. A separation from his wife in 1978 occurred in tandem with a return to religion. His great friend, the great poet Gwen Harwood, quotes him saying “I was born inside the front cover of the Old Testament,” and his late experience with born-again Christianity should be seen in light of his parents being deserters of the Exclusive Brethren. In the midst of this turbulence, a diagnosis of brain cancer, and then lung cancer, arrests Tanner’s journey. He remarries his wife a month before dying.

Most of Tanner’s best circuit board abstractions have been placed in collections already, but I would love to hang the Aries painting next to a really good example of this earlier style. I imagine the contrast illuminating the difference between number maths and star maths, and that difference illuminating the whole of something. I am grateful to see this example of one man’s unpredictability, if only for the briefest reminder that within a single soul a person can abruptly change directions.

Victoria Perin is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne.