Eavesdropping

Sophie Knezic

Double Issue

This week Memo Review publishes two reviews of two major exhibitions currently open at the Ian Potter Museum of Art: State of the Union and Eavesdropping.

Below Sophie Knezic considers the social and political stakes of the question of sound, surveillance and listening in Eavesdropping.

Eavesdropping

Ian Potter Museum of Art

24 July – 28 October

By Sophie Knezic

The most iconic disciplinary schema brought to late 20th century philosophical attention would, without doubt, be the Panopticon; a model of surveillant architecture devised for the redesign of prisons at the end of the 18th century by the British reformist Jeremy Bentham. Almost 200 years later, Bentham's brutally efficient structure was positioned by Foucault in his study of the prison system as the reigning emblem of biopower; not just a landmark in the transformation of Western penal architecture but a diagram of the new economy of internalised self-disciplinary and self-surveillant rule.

Lesser known is the antecedent model of patrolling architecture proposed by the 17th-century German Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher. In his musicological two-volume text, Musurgia Universalis (1650), Kircher provided a sketch for a system of regal surveillance: three huge shell-like horns embedded into the walls of a piazza and curling into an upper storey palace room, enabling eavesdropping through amplifying the activities taking place below.

An antiquarian copy of Kircher's tome showing the illustration flanks the entrance to the exhibition Eavesdropping, adjacent to William Blackstone's similarly hefty volume on English jurisprudence published in 1769, open at the page on the legal definition of eavesdropping. Eavesdropping, now understood as listening without consent, originally referred to listening under the eaves of a house 'to frame slanderous and mischievous tales', and was one of the most reported common law offenses in the local courts of 15th-century England.

These entwined architectural, legal and biopolitical precepts ground Joel Stern and James Parker's politically conscientious and astutely curated exhibition. While the ubiquity of surveillance is a reality of which we are implicitly aware, we mostly think of it in visual terms: public and corporate premises installed with CCTV cameras or GPS-tracking of our every digital move. Eavesdropping builds a case for the more ominous reality of unauthorised listening as a form of sonic surveillance; more sinister because its mechanisms operate beneath the level of conscious awareness and are mired in politico-legal complexity.

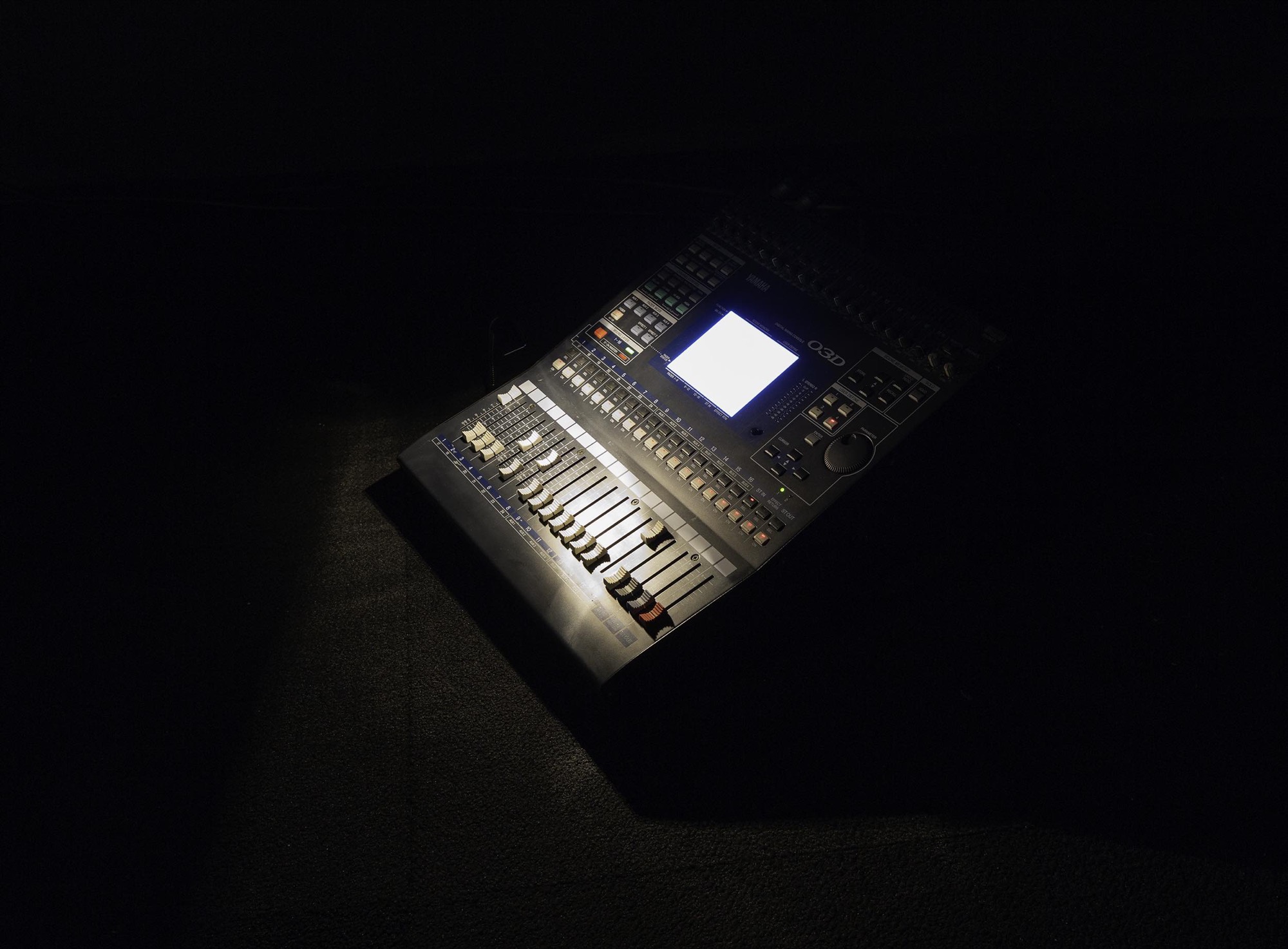

The implication of eavesdropping as motivated by pernicious intent is apparent in Sean Dockray's short video Learning from YouTube (2018) and Susan Schuppli's sound installation The Missing 18 ½ Minutes (2018). Schuppli in particular has focused her practice over the last 20 years on the subject of eavesdropping and this exhibition presents a suite of archival photographs relating to the political scandal of the White House tapes: the Nixon Administration's illicit audio-tape recordings in the Oval Office taken between 1971-73, in particular Tape 342 and its infamously erased 18 ½ minutes. This section of the tape—along with a facsimile of the original technical investigative report—forms the crux of Schuppli's installation; and donning headphones one is able to listen to the crackling recording shot through with buzzes and the occasional beep—an opaque sonic experience of constitutional silence.

In parallel, Learning from YouTube uncovers a more contemporary scenario of constantly occurring sonic digital surveillance. While data mining immediately brings to mind the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica and the March 2018 exposé of its harvesting of personal data of millions of Facebook accounts deployed for political campaigning, Dockray's video reveals the systematised practice of audio capture undertaken by giants such as Google in its 'audio ontology' program—a digital archive of 200 million sounds ordered into a taxonomy of 632 types—as well as private audio analytics companies capturing and interpreting troves of sounds through advanced algorithmic processes that trigger the dispatch of police personnel to scenes of potential crimes before they actually occur. Learning from YouTube exemplifies the new modalities of social control diagnosed by Gilles Deleuze in his assertion that the disciplinary societies theorised by Foucault have transposed into 'societies of control'—where earlier regulatory institutions such as the factory are supplanted by the more protean and dispersed mechanisms of power exerted by multi-national corporations. In this regime, humans are reduced from individuals to 'dividuals'—to the status of codes, markets and data.

The disciplinary measures of incarceration, nonetheless, still prevail, made achingly apparent in the brutalising conditions of places such as the Saydnaya Military Prison in Syria. Lawrence Abu Hamdan (like Schuppli) is associated with the London-based interdisciplinary research agency Forensic Architecture, known for its development of highly sophisticated evidentiary methods and partnering with human rights bodies in the investigation of international human rights violations. To produce Saydnaya (the missing 19dB), (2017), Abu Hamdan collaborated with Amnesty International in an investigation of this military prison located north of Damascus. The resulting 12-minute sound installation exposes the violence inside the penitentiary and provides an extraordinary insight into the potentially lethal consequences of silence and speech in such an environment.

The prison, still in operation, has been kept inaccessible from human rights organisations, journalists and independent monitors so that enquiry into the estimated 15,00-17,000 deaths and disappearances occurring since 2011 has had to rely heavily on the testimonies of former detainees. Saydnaya (the missing 19dB) focuses on the testimony of a survivor who narrates the ways in which sound came to operate as a hinge between life and death. The guards frequently assaulted the prisoners, but to scream while attacked was prohibited; those who did so could be beaten to death. Private conversation between the inmates was only possible surreptitiously, through whispering, and the former detainee describes how whispering for the length of her incarceration resulted in a deformation of her tongue and the incapacity to properly speak after her release. Pre-dawn round-ups of inmates into departing trucks portended disappearances and the 15 minutes of silence before the trucks' return connoted summary executions. 'Silence', she notes, 'is what allows you to hear everything', giving a devastating twist to the experimental composer Alvin Lucier's assertion that 'careful listening is more important than making sounds happen.' In the words of this survivor, 'Silence is a form of torture in and of itself.'

Another work by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Rubber Coated Steel (2016), extended the contention that sound can kill. This time working with the human rights organisation, Defence for Children International, Abu Hamdan investigated the murder of two unarmed Palestinian teenagers in the occupied West Bank territories, Nadeem Nawara and Mohamed Abu Daher, shot to death by an Israeli bodyguard. Rubber Coated Steel restages the investigative report as a video tribunal, pivoting on audio-ballistic evidence. In a meticulously argued account, the prosecution probed the different acoustic properties of real bullets and rubber-coated ones. Accustomed to the frequent sound of gunfire, it was revealed, the teenage Palestinians had developed expertise in differentiating the sounds emitted by rubber bullets opposed to live ammunition. Upon realising this, the Israeli soldiers took measures to alter the sonic properties of gunfire; by fitting the barrel of a M16 rifle with a rubber bullet adaptor to suppress the sound of lethal bullets, allowing them, in the words of the prosecution, 'to kill with impunity'.

Conversely, for others, the very capacity to hear can be impeded through pernicious medical neglect. Joel Sherwood-Spring's Hearing Loss (2018) presents a recorded conversation between the Wiradjuri artist and his mother, the activist and health worker Juanita Sherwood, on the subject of Otitis Media—a disease of the middle ear—from which both Spring and Sherwood suffer. Sherwood's recollections of working in Redfern, Sydney in the early 1990s with indigenous children disclosed the high rate of cases of this condition, which left untreated can develop into tumours and permanent hearing loss. Sherwood's brief accounts of severe cases—one where the untreated disease had eaten away the bones of the inner ear beyond the possibility of surgical treatment—were on a number of levels hard to hear: the volatile volume of the conversation replicating the inconstancy of sound experienced by those afflicted with this condition.

The national shame of Australian federal policy on refugees presses home in perhaps the subtlest work in the exhibition, How Are You Today? (2018), produced by the Manus Recording Project Collective. Commissioned especially for Eavesdropping, the work is a collaboration between six men incarcerated on Manus Island and three resident in Melbourne, and comprises a series of 10-minute sound files recorded daily by the men on Manus, transmitted and uploaded to the Ian Potter Museum for looped playback on the same day, producing an ongoing archive of sound files for the duration of the exhibition. The recordings bristle with immediacy and gravitas.

As I write, the medical agency Médecins Sans Frontières has urged the Australian Government to immediately evacuate the asylum seekers imprisoned on Nauru, joining a litany of international human rights organisations that have previously advocated for this. The prevalence of human rights violations cuts across many of the works in Eavesdropping, and the exhibition is suffused with an awareness of how this urgent and disconsolate reality is instrumentalised by sound. As the French musicologist Jacques Attali reminds us, eavesdropping, recording and surveillance are weapons of power—but not beyond contestation. The world is audible and sound itself is a political economy; as its denizens we must prick up and ears and listen.

Sophie Knezic is a writer, academic and visual artist who lectures at VCA, the University of Melbourne and at the School of Art, RMIT University.