Douglas Lance Gibson: What Was Once Yesterday Today & Tomorrow

Francis Plagne

As I was about to leave Tolarno Galleries after spending some time with Douglas Lance Gibson’s What Was Once Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow, his first show with the gallery, I was stopped by two men. One, who I assume was some sort of building manager, informed me that a theft in the gallery had just been reported and politely requested that I remain on the premises while we waited for the police to arrive; the other, who I later guessed belonged to the Victorian office of the Liberal Party housed one floor down from Tolarno (maybe the thief got lost on the way up the stairs?), stood silently by with a solemn expression. Having half an hour on my hands to kill, I happily complied with my somewhat arbitrary detention and waited for the police to arrive. Being the only visitor to the gallery at the time when the theft was noticed, I was of course the number one suspect, though when the police eventually showed up, they didn’t seem too hopeful as they casually searched my bag before declaring me free to go. Before the arrival of the police, I took the opportunity to spend a little longer with the works in the show, and the oddly dragging temporality of waiting provided the perfect attunement with which to appreciate Gibson’s photographs; works that are concerned above all with complexities and paradoxes of time.

Archival pigment print, coconut timber frame, 70 x 56 cm.

As many commentators on the medium have noted, photography generates a powerful experience of temporality. Opening and closing the shutter inscribes the light of a particular moment of time onto the photographic medium, yet our temporal experience of the final image (even one intended to perform a purely documentary function) is far from simple. Every photograph exists at the intersection of a manifold of distinct yet overlapping temporal orders: the measurable time of the instant captured, the subjective time of memory, the time of the world from which the instant was captured. Much of Gibson’s work takes the temporality specific to his medium as its explicit concern. In a series from 2013, After the Birds Have Flown, Gibson presents a sequence of near-identical images of a birdhouse immediately after it has been abandoned by birds, meticulously documenting location, date, time, and species of departed bird in the title of each work. Here the awareness, intrinsic to our perception of documentary photography, that the image we see was preceded and followed by moments now inaccessible to our gaze becomes the very subject of the work: it is the documented event itself that, paradoxically, we cannot see. Gibson dramatises what Belgian art critic Thierry de Duve has called documentary photography’s ‘sudden vanishing of the present tense’, its ‘splitting into the contradiction of being simultaneously too late and too early’.

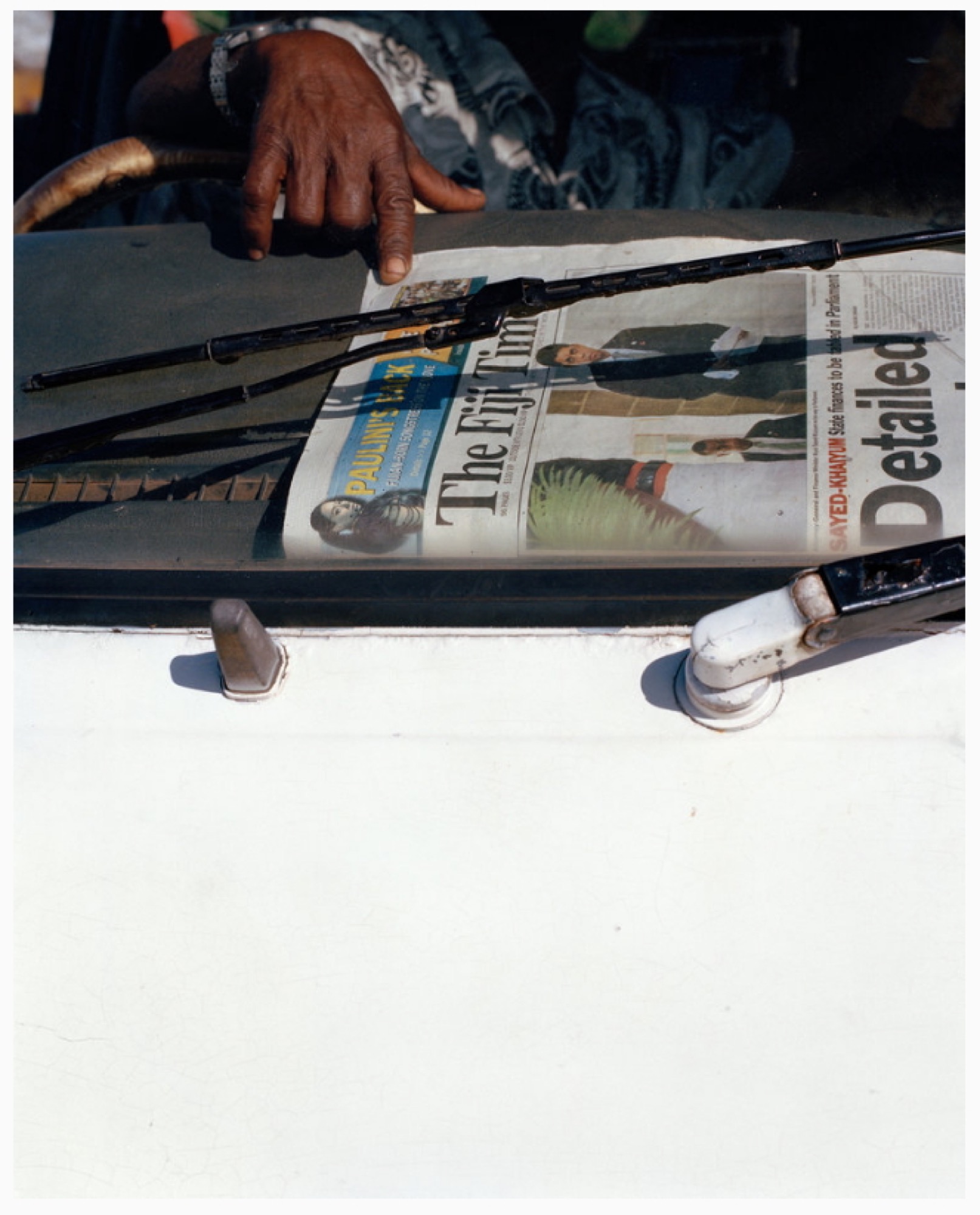

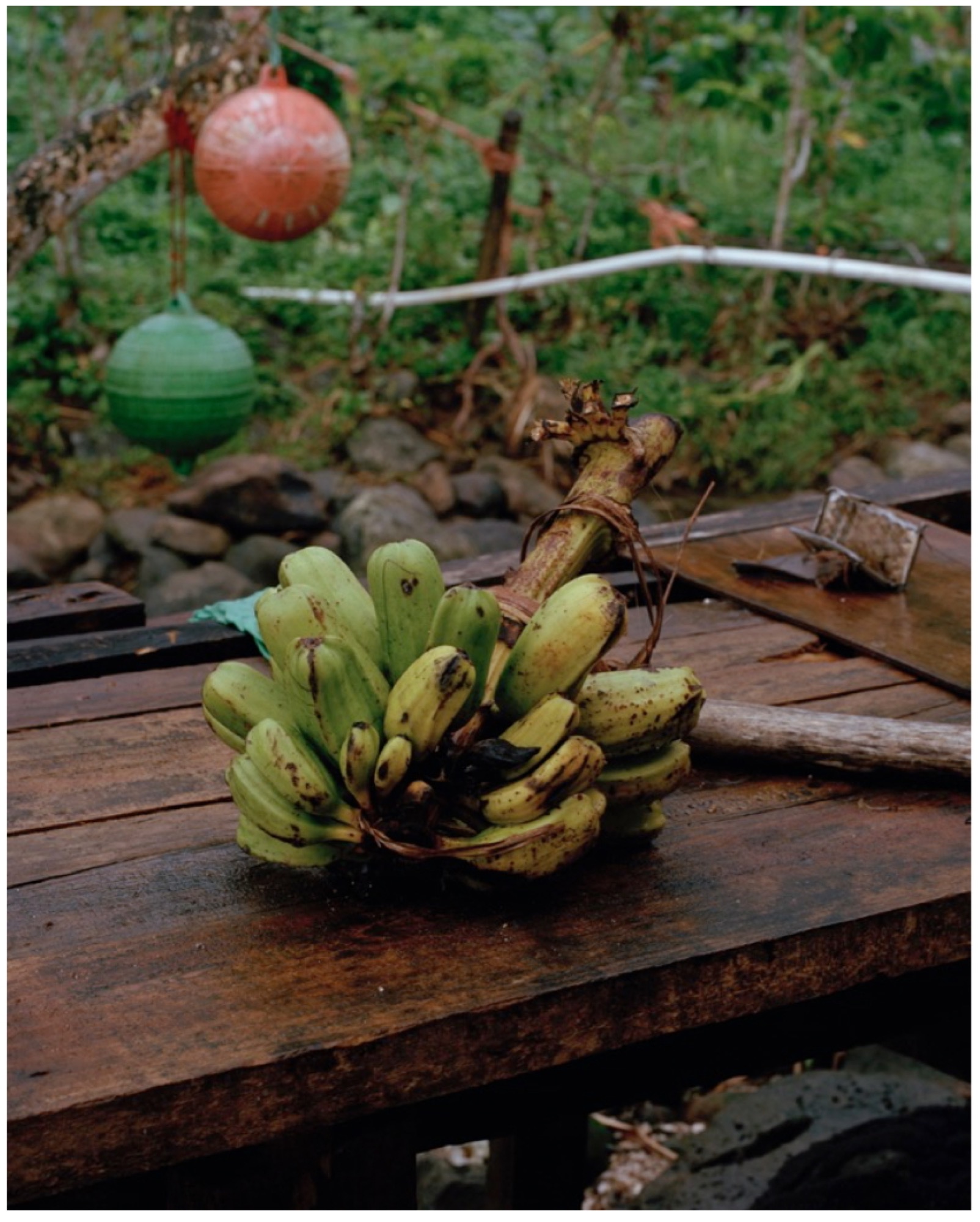

The series on display at Tolarno, What Was Once Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow (2014-2017), expands this concern with temporality in a cultural direction through a series of photographs taken on the Fijian island of Taveuni. The title of the series poetically alludes to the fact that the 180th meridian, used to determine the International Date Line, runs through the island, allowing, as the artist writes in an articulate text that accompanies the show, ‘the local Fijians to, in theory, travel forwards and backwards in time’. Some photographs in the show refer directly to the geographical-temporal anomaly of Taveuni; one, for example, captures the beautifully faded rose façade of the Meridian Cinema (2014). More broadly, the arbitrary nature of the International Date Line as a construct becomes the impetus for a series of images that reflect on the coexistence of the quantified, chronometric time often associated with the West and another order of temporality found in the rhythms of nature. Images of The Fiji Times (Fiji Time I, 2014), clocks (Fiji Time II, 2014), and a weathered film projection booth (Meridian CinemaII, 2014) become figures of the construction and measurement of time through minutes and seconds, publication schedules, and frame rates, against which images of plants (including one of my favorites, Vudi (Plantains), 2014, a bunch of the titular fruit that sits outdoors on a wooden table, resonating with the abandoned mystery of de Chirico’s bananas) and a series of images of darkly gleaming water gesture toward the simultaneous existence of another, fundamentally different, order of time.

While the series as a whole has a conceptual underpinning, the individual photos are closer to snapshots, quotidian moments captured in a rich, sensuous colour that gives a powerful sense of the dampness of the location’s tropical atmosphere. Some of the strongest works in the show depict banal scenes of commercial life (shelves of tinned fish, a shop counter stocked with eggs, the cyan façade of a general store glowing under lights at night) emptied of human presence in a way that recalls Stephen Shore’s images of eerily depopulated American suburbia. Less successful are some of Gibson’s depictions of human figures, such as Siga Tabu (Sunday, 2014), a tightly cropped image of a young man in his Sunday best, which hovers somewhat uncomfortably between a portrait and an oddly depersonalised exemplar of Gibson’s concern with temporal rhythms. Far better are those images where Gibson fills the frame with flat surfaces, such as Vale Ni Lotu II (Church), 2014, which casts a painterly eye at the weathered texture of a church ceiling.

Archival pigment print, coconut timber frame, 40 x 50 cm.

Handsomely presented in coconut timber frames, the works occupy the space of the gallery more boldly than the average exhibition of photographs, partly because of an unorthodox hang in which frames abut the edges of walls and are sometimes grouped together to form irregularly shaped triptychs of differently sized photographs. This engaging physical presence makes Gibson’s choice to accompany the photographs with a line of river rocks from Taveuni along one wall of the gallery feel like an unnecessary addition, as if the artist is second-guessing the photographs’ ability to stand on their own. He certainly has no need to worry: the photographs are both physically commanding and communicate a sense of locality that transcends the vaguely touristic atmosphere imparted by the rocks. Similarly, the most recent piece in the exhibition, a video work shown in the small back gallery (Yaboca NaIsema (Feeling for the Seam), 2017) made up of long, mainly stationary shots of cooking, fishing, children playing and so on, while attractive enough in its own right, feels almost jarringly linear in comparison to the experience of viewing the photographic works in the main gallery. Unlike the literal, linear temporality of the video work, in Gibson’s photographs the differing temporal orders of everyday life, measurement, and the natural cycle of birth and decay intertwine to create a dream-like, suspended sensation, punctuated by the meditative interludes provided by the three large, brooding images of rippling water (Waibula I, II, and III, all 2014) spread across the show’s main room.

In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant remarks that we can only represent time as a spatial figure: specifically, a straight line. In Gibson’s series, the most unlikely and diverse images become representations of the passing of time. Even the bloody line created by the movement of a knife through a fish in the process of being filleted (Sila Sila (Barracuda), 2014) appears as a temporal marker, representing the time taken to perform the action. As this image demonstrates, although Gibson’s work articulates complex concerns, it is far from dry. Rather, his images inhabit a poetic register where details from the surface of our sensual world are quietly monumentalised and allowed to embody, rather than merely illustrate, rich ideas about time, history, and culture.

Francis Plagne is a writer and musician from Melbourne.

Title image: Douglas Lance Gibson, Sila Sila (Barracuda), 2014

Archival pigment print, coconut timber frame, 40 x 50 cm.)