documenta fifteen

Paris Lettau

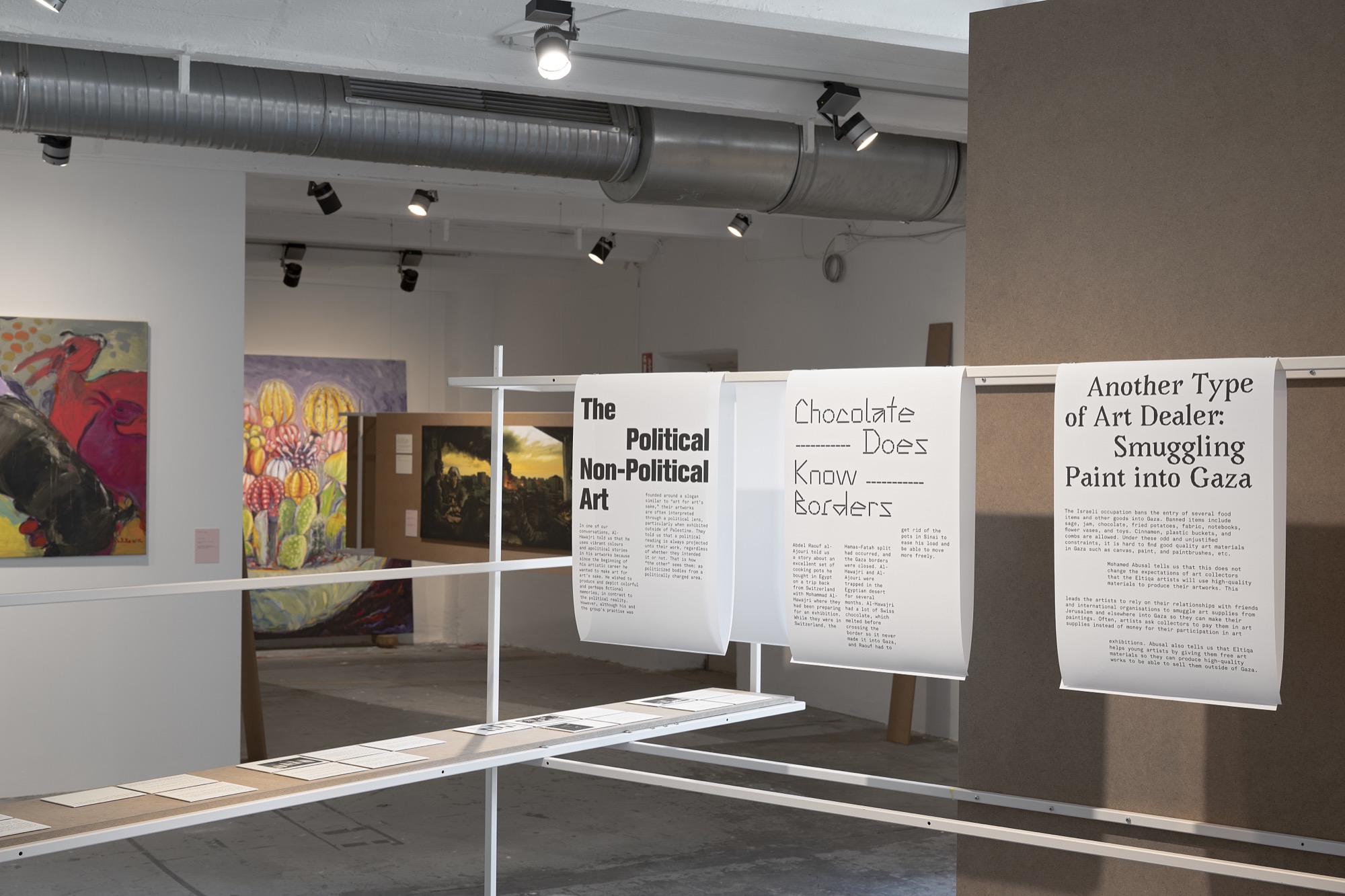

Between the majestic Kassel Kongress Palais Stadthalle and two charming little classical-style buildings that once housed Joseph Beuys’s University of the Trees, there is an inconspicuous tram-stop advertisement for documenta fifteen. Under a photograph of ruruHouse (the “living room” of the exhibition) is written “Kunst gehört nicht nur an die Wand. Sondern in die Mitte der Gesellschaft” (Art doesn’t only belong on the wall. But in the middle of society). As advertised, the latest instalment of the most important international exhibition of contemporary art has flung an artistic community of communities into the middle of contemporary German society. How do they fare?

The original motivations seem noble enough. For sixty years, documenta has appointed a European (with the exception of Okwui Enwezor in 2002) superstar curator to showcase to the world the cutting edge of contemporary art and discourse. This year, documenta gGmbh (a limited liability non-profit organisation owned by the City of Kassel and the State of Hesse, and whose director is Sabine Schormann) has commissioned ruangrupa as artistic director, a ten-member Jakarta-based artists’ collective founded in 2000. “Make friends, not art” is their motto. It has resulted in a documenta that, at least when I was there, was one of the most uplifting, energising and hopeful exhibitions I have seen in a long time (once I got used to the absence of the “curated art” one usually expects from a biennale).

ruangrupa has based documenta fifteen on the idea of “lumbung”, which directly translates as “rice barn”, and refers to a communal building where a community’s harvest is gathered and distributed as a collective resource. Fourteen collectives and a handful of individual artists were initially invited by ruangrupa. In the spirit of lumbung, the production budget was then gathered into a shared “pot” and distributed according to a collective decision-making system based on ten assemblies called majelis. Larger majelis akbar were also held, in which further artistic decisions were made collectively. The lumbung members were empowered to invite additional artists and collectives, resulting in a transnational network of around fifty collectives and 1,500 artists (no one seems to know the exact figure).

But the very concept of documenta fifteen makes it impossible to capture the sheer magnitude of collectives, artists and programs across this constantly transforming 100-day exhibition. Included are archivally-focussed collectives like The Black Archives, Asia Art Archive and the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie. There are collectives supporting specific communities such as the Party Office b2b, which hosts queer night clubs, and Trampoline House, which supports refugees in Copenhagen. There are community arts organisations like Trinidad and Tobago–formed Alice Yard, Thailand-based Bann Noorg, and Boloho from Guangzhou, China. There are art education collectives such as Another Roadmap Africa Cluster from Uganda; activist collectives like the international Arts Collaboratory; and artists collectives like Aotearoa’s Indigenous queer collective FAFSWAG, Pari from Sydney’s western suburbs, or the Syrian-based film collective Komîna Fîlm a Rojava (The Rojava Film Commune).

Behind the collectivist positivity is an agenda of critique and healing. In 2019, ruangrupa declared that “if documenta was launched in 1955 to heal war wounds, why shouldn’t we focus documenta 15 on today’s injuries, especially ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, or patriarchal structures, and contrast them with partnership-based models that enable people to have a different view of the world”.

Richard Bell sets the tone. He’s pitched his now iconic Tent Embassy (2013–) right in the middle of Kassel’s central civil square, Friederick Platz, and out the front of documenta’s main venue, Fridericianum. While one of the few solo artists invited by ruangrupa, Bell brings with him two collective spirits: the spirit of ProppaNow, the Brisbane-based art collective founded in 2003, and the spirit of the original Aboriginal Tent Embassy that began in 1972 at the Old Parliament House in Canberra, now a symbol in Australia of the principle that sovereignty was never ceded to the British colonisers. Adorning the Fridericianum is Bell’s giant Pay the Rent (2022), which looks like a ticking time bomb except it counts up—displaying a quickly-growing debt owed to Aboriginal people by the Australian Government from 1901 to now.

Bell’s work somehow ties together the Fridericianum too, beginning with Tent Embassy on the front lawn. In the basement next to the toilets is his upturned Duchampian urinal, which, adorned with sad Koonsian helium balloons, characteristically takes the piss. His iconic protest paintings command the entrance and exit vestibule, and his recent White Lies Matters painting is pitched high-up in the stairwell, which is passed as one is angelically elevated up each level of the building, until reaching the apotheosis on the third floor where there are yet more of Bell’s paintings. When I arrive, I find Bell himself there as if walking on clouds; his contagious, performative energy is on full display for a film crew shooting a forthcoming documentary about him, entitled You Can Go Now. I go.

That night, Bell was once again a star singing karaoke at ruangrupa’s welcoming dinner at the opening celebration hosted at the Gud Kitchen, with food catered for by the artists. They served up an infectious energy of optimism.

The public opening night kicked off with as much of a bang. Thousands of Kassel locals jubilantly sang along to a concert-like, artist-led karaoke in Friedreich Platz, to hits including Bon Jovi’s ‘It’s My Life’ and Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. It was more popular than populism.

In fact, parts of documenta fifteen would not be out of place at a populist exhibition in a big city’s major art institution. The playful and humorous Gudskul has turned Fridericianum into a kind of education-centre called Fridskul (this cute, playschool language is used frequently). Gudskul has a Steiner-style critique of traditional art education institutions, and their Nongkrong Curricula is based on the activities of “Friend-Making, Learning from Friends, and Self-Organising”. Got kids? No problem. RURU KIDS provides day-care on the ground floor too. And artist and educator, Graziela Kunsch, facilitates parent and baby groups where babies can “move freely, and do their research”, without the parents directing the play. There’s skateboarding, too, with a halfpipe supplied by Thailand-based Baan Noorg’s Churning Milk: the Rituals of Things (2022).

Aside from the participatory-based installations, there are also more curated displays. The Cuban collective Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt, founded by artist Tania Bruguera, presents a powerful and moving exhibit of art and artists excluded, censored or disappeared under the Cuban regime. A standout was also the various DIY assemblages and political works by Haitian collective Atis Rezistans at the desacralised St. Kunigundis Church, which had an edge reminding me of the Tennant Creek Brio—a collective, equally concerned with trauma and healing, who would have served this documenta well.

The apparent victory of community at documenta doesn’t go uncontested—but when it is challenged it comes with an edge of critique. Anwar Al Attrash’s Red Carpet (2022) installation, running from floor to wall to ceiling, suggests a dream of becoming a topsy turvy celebrity. This longing for individuality sets the tone of *fondationClass* Collective, which is based out of the Weißensee Art Academy in Berlin and supports people who have been refugees or migrants. The group’s colourful textiles hang through the Fridericianum’s three-storey atrium, at times declaiming against the strictures of institutionalised collectivist categories. One reads:

We want to challenge the narrative that we are seen through in our physical realitie(s). The narrative that makes us always appear as groups. The narrative of every German cultural institution that only acknowledge us collectively and never as individuals worthy of self expression.

There has therefore been plenty of the usual cynicism in the critical responses to documenta fifteen, including unexciting calls for a return to the “strong curator” from the likes of Fluxus artist Bazon Brock, who has been rolling in his grave even if he’s still alive. Klaus Biesenbach and Hans Ulrich Obrist are rumoured to have boycotted the exhibition. So what.

Altogether one is reminded of the more interesting critical debates of the 1980s, when the grassroots collectivist enthusiasm of artists who came of age in the 1970s reached full maturity. The Australian conceptual artist and former Art & Language member Ian Burn, for example, dedicated a good part of his life to union community art, but came out the other end a bit disillusioned. “There is a problem of the quality of the visual arts projects”, he said, which is “highly positivistic and one dimensional” and “can’t be passed over by simply saying it is a ‘different quality’”. There are certainly comparable soft targets at documenta fifteen, but that goes for any other biennale. (A funny story: Art historian and close friend of the late Burn, Terry Smith, who in his review of documenta fifteen sees a reflection of the good old days of artist collectives, is said to have once had a practice of dressing in a Mao suit and, instead of going to bourgeois art galleries, took his students to local community farmers markets to see the fruit arrangements. Those students retaliated by becoming post-modernists.)

Perhaps predictably, then, responses to the artistic premise of documenta fifteen have included a suspicion of its glowing collectivist rhetoric. They have also included an ethical or political solidarity with ruangrupa’s underlining critical agenda. But don’t be mistaken, the two go hand in hand. One need only compare documenta fifteen with the more cerebral, critical and predictable approach to decolonialism in Kader Attia’s Berlin Biennale. Its problems-based approach contrasts sharply with ruangrupa’s ethos of solutions. The collective takes seriously documenta’s original raison d’être as a post-war institution of soft power and come to the European table with a populist “hearts and minds” campaign. Documenta gGmbh’s Finding Committee was looking for just this: “We have appointed ruangrupa because they have demonstrated the ability to appeal to various communities, including groups that go beyond pure art audiences, and to promote local commitment and participation”. Has broader German society opened their hearts and minds to ruangrupa’s Pax Indonesia?

Antisemitism

It seems not. It started with a pre-emptive strike in early 2022. A blog some have said to be associated with antideutsche (a left-wing anti-nationalist and sharply pro-Israel political faction) made unfounded accusations of antisemitism against ruangrupa. The mainstream German media uncritically propagated the allegation, which hinged primarily on the inclusion of the Palestinian collective The Question of Funding and various associations with Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS), a Palestinian-led movement that promotes, well—boycotts, divestments and sanctions against Israel. Since 2019, BDS has been designated antisemitic by the German Parliament, for whom the air of an Israeli boycott smells of the Nazi-era boycott of Jewish businesses under slogans such as “Don’t buy from Jews”, making it a highly charged association in Germany capable of triggering the most frenzied media carnage.

Then a panel entitled “We need to Talk! Art — Freedom — Solidarity” was cancelled after criticism by the Central Council of Jews in Germany, which led one participant, the sociologist Natan Sznaider, to withdraw in solidarity. Two weeks later, the WH22 documenta venue was broken into and graffitied with effective death threats: “187”, the California Penal Code for murder, and “Peralta”, the name of a well-known Gen-Z fascist, were scrawled across the exhibition space.

So, when the documenta fifteen media preview opened, which ran from Wednesday 15 to Friday 17 June, the press was busy running around documenta’s sprawling 30,000 square metre geography with magnifying glasses in hand, scouring everything, determined to find the smoking antisemitic gun. Nothing.

Until opening day, Saturday 18 June. The German President Frank-Walter Steinmeir made an unprecedented political intervention into documenta, arguing that it had to respect the local German sensibilities. He waved his finger at documenta gGmbh and drew a line in the sand: artistic freedom allows for the questioning of Israel’s policies, he said, but not the questioning of Israel’s existence. The Federal Government was speaking out both sides of its mouth. As Steinmeier cautioned documenta gGmbh to above all ensure open and complex discussion continued, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who is a “big fan” and has not missed a documenta in thirty years, announced he would boycott it this year. No ifs, no buts. No discussion.

As Steinmeier lectured at Documenta Halle, his police drones buzzing around outside menacing peaceful visitors, a new banner foisted up the night before (unseen during the press preview, as it required urgent repairs) was beginning to cause a stir. Antisemitic caricatures were found hidden in plain sight: in the most prominent work of the exhibition at Friedreich Platz. It is by now well-known that the offending work was the giant, 100 square-meter agitprop banner People’s Justice (2002) by Indonesian artist collective Taring Padi. One figure is an orthodox Jew with side-locks, blood-sucking fangs, and burning red eyes, wearing a black bowler hat emblazoned with the Nazi insignia SS. Another figure wears a scarf with a Star of David on it and a helmet with the words “Mossad”. A soldier with a pig’s face could also be seen on the large banner.

Taring Padi have explained in a public apology the origins of the work. It was produced in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2002 for public exhibit in genteel Adelaide in response to the rule of Suharto’s military dictatorship and the Western-supported Indonesian genocide of 1965. Likewise, ruangrupa have explained the colonial-context of the antisemitic figures, which were inherited from the Dutch colonisers of Indonesia who used their armoury of antisemitic tropes against Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese people. Talk about a return of Europe’s repressed.

Some readers may be puzzled. Why had all this political tinder of antisemitic suspicion been laid in the first place, prior to it being set alight by Taring Padi’s banner in a wildfire that threatens to consume all of documenta fifteen? Richard Bell is right to point out that it is explained by a widespread and underappreciated Islamophobia in elements of German society. But this is only part of the story. The reality is documenta fifteen has landed in the middle of an intense culture war in Germany, in which a battle over the nation’s political memory is being waged in the most unforgiving terms.

It took decades for the view to prevail in Germany that the Holocaust was the central atrocity of the Nazis. In the 1990s so-called Historikerstreit (historians’ dispute), Jürgen Habermas won (to put things in grossly simple terms) the debate against the right-wing historian Ernst Nolte, whose antisemitic arguments sought to relativise the Holocaust under the cover of other war-time atrocities. It has been since then an unwritten basic law of Germany’s political memory not to question the singularity of the Holocaust.

More recently, the rise of populism and contemporary forms of antisemitism that it instrumentalises has led both government and civil society in Germany to sharpen its weapons, including by adopting a new definition of antisemitism. In 2017, the German government adopted a definition drafted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) which states that “manifestations of antisemitism can also be directed against the State of Israel, which is thereby understood as a Jewish collective”—but the German government removed a qualifying second clause in the IHRA definition: “However, criticism of Israel, which is comparable to that of other countries, cannot be considered antisemitic”.

Then there was a scandal comparable to documenta fifteen, raised even by the AfD in the Bundestag last week: the Cameroonian scholar Achille Mbembe was accused in 2019 of antisemitism for comparing Israel to apartheid South Africa—former New South Wales Premier Bob Carr also did so last weekend—and for relativising the singularity of the Holocaust by placing it in a globalist perspective, within the history of colonialism (hardly ground-breaking—Hannah Arendt already did this in her 1951 The Origins of Totalitarianism, as did Aimé Césaire).

Thus, two main trigger points have emerged on the battlefield of a new culture war: criticism of Israel (whose protection Angela Merkel has stated is Germany’s raison d’état) and perceived relativisation of the Holocaust.

Within this culture war, Mbembe is associated with a new transnational memory culture that is interrupting Germany’s long-stable politics of memory centred on the singularity of the Holocaust. This transnational memory culture not only tries to tell different stories of violence (the Herero and Namaqua genocide, people fleeing war, Europe’s own political and familial stories of violence, colonial cultural dispossession, the list goes on) but also to understand the Holocaust from a globalist, non-provincial perspective. The buzzword is “multidirectional memory”, which a new generation of cultural leaders use to describe a more inclusive memory culture in Germany, rejecting what they consider to be a zero-sum-game, winner-takes-all memory culture, where victims fight for victim supremacy in a battle for the soul of national remembrance.

It is easy to point to documenta gGmbh’s embeddedness in these controversies. Finding Committee member Charles Esche, for instance, asks in an influential 2019 scholarly article with Cristina Buta about the apparent imbalance in Germany between monuments addressing the Holocaust and those addressing genocidal crimes of colonial occupation. He says that he looks forward to a coming monumentalising process in the public spaces of European cities.

This second Historikerstreit, sometimes called “the German Catechism”, is the cultural war documenta fifteen lands in. The exhibition was from the beginning a hazardous territory on which would be conducted a complex array of proxy wars. Indeed, it is likely that a motivating factor for selecting ruangrupa as artistic directors of documenta fifteen was precisely to intervene in this uniquely German conflict that echoes across Europe. One wonders if ruangrupa was properly appraised of this.

Whatever the case, since the display of the Taring Padi banner, they have found few allies willing to risk defending the view that the banner should not be removed. Even the weirdly-named Initiative GG 5.3 Weltoffenheit (Initiative GG 5.3 Cosmopolitanism), formed after the Mbembe affair and BDS resolution by the giants of German culture to protest against interference in freedom of artistic expression, have publicly declared it “unequivocally necessary” to remove the Taring Padi banner.

Michael Rothberg, who popularised the term “multidirectional memory”, has come to documenta fifteen’s defence. He casts the exhibition as an opportunity for Germany to unlearn its prejudices, but he is not overly optimistic. In the centre-left Berliner Zeitung, he writes that:

So far, Germany’s “anti-Semitism” guardians have used a disturbing image in a 20-year-old political artwork, created in a radically different context, to exploit the charge and to confirm their own prejudices about the so-called Global South and “post-colonialism”—arguably one of the vaguest and most distorted epithets in Germany today.

It is thus evident to many that antisemitism has been used as a cover (under which are hidden all sorts of motives, including the Islamaphobia Bell points to) to fight proxy wars against this vaguely defined “post-colonialism”.

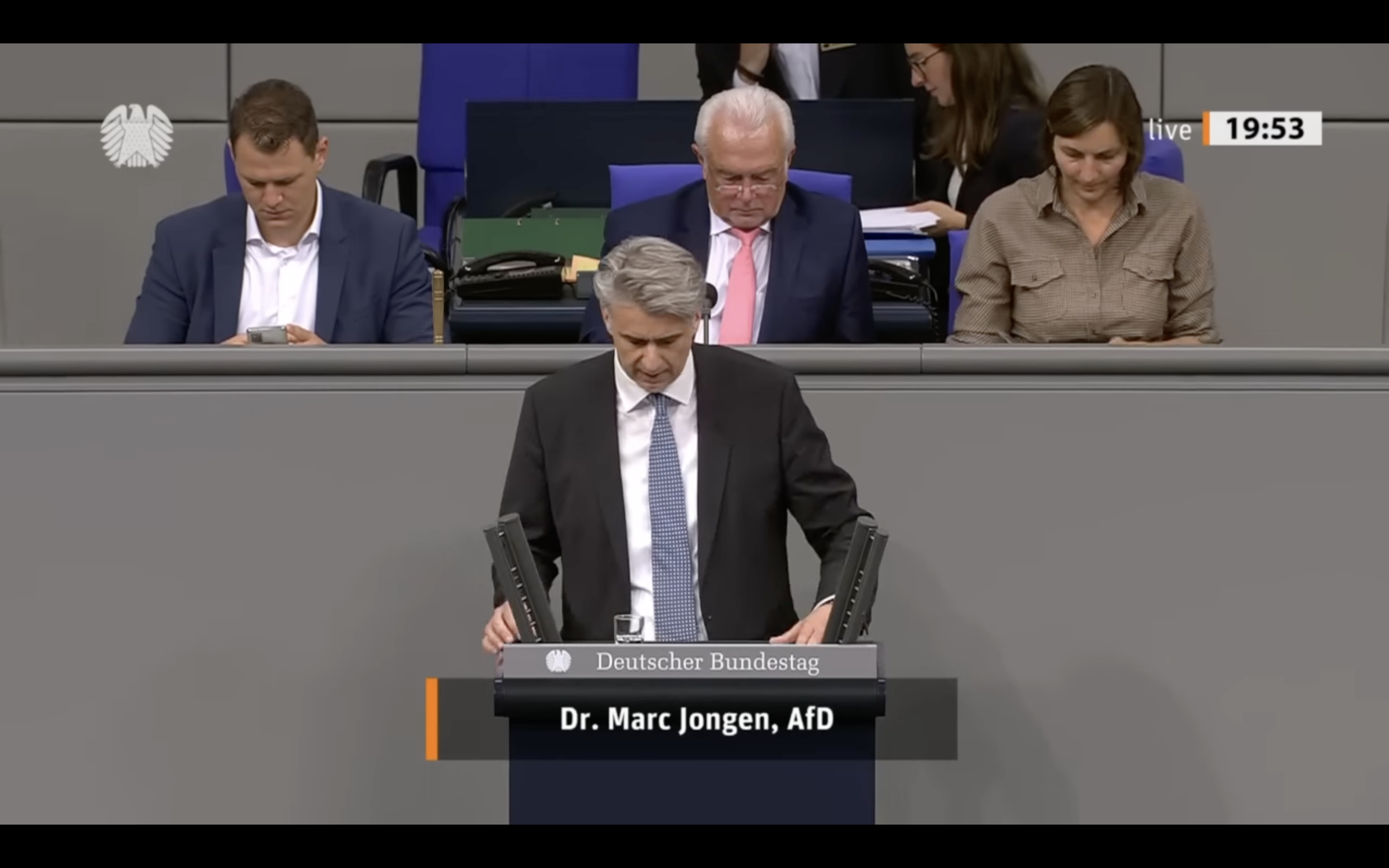

The most extreme case of duplicity was the far-right member of the Hesse State Parliament and AfD Hesse (a party known for its own brand of antisemitism and Islamaphobia) Frank Grobe, who gave a speech in Parliament declaring the New York-based online publication platform e-flux, which published an early statement by ruangrupa, also to be antisemitic, adding that “antisemitism seems to be en vogue in the artistic milieu”. He called on the Parliament to “cancel documenta immediately”. The AfD also sought in the Bundestag last week to issue a decree against post-colonialism.

Sensing a fundamental shift in the balance of cultural power in Europe, a generation of cultural elites have experienced the post-colonial and decolonial ideas that motivate documenta fifteen as a kind of reverse colonisation of Europe by the so-called Global South. Conservative philosopher Peter Sloterdijk spoke with a critical tone of the “mobilisation of a post-colonial culture”, in which “intellectuals from the periphery” were getting ready “to take power in the centre”. The sociologist Natan Sznadier likewise interprets ruangrupa as being part of a “cultural-political milieu who are becoming the new hegemony”. Scary stuff, for these guys.

But even participating artist and German Professor of Art, Hito Steyerl, weighs in. Before documenta opened, she made accusations of a badly corrupted post-colonial and decolonial discourse. She uncompellingly cites Vladmir Putin’s decolonial discourse (vis-à-vis Russia invading Ukraine) as one example of such corruption. She worries about a return to an “alternate version” of the first historians’ dispute, in which “Nolte might have won this time”. But she also questions the popularity of Mbembe in Germany, claiming that by speaking lyrically of an “abstract ‘colony’ that seems to have no real location” he seems to have appealed to German intellectuals “since everyone could think that this abstract colony was reassuringly far away—and the Humboldt Forum did not own any looted art from there”. And she warns, as if having made her mind up about documenta fifteen, that “criticism of colonialism often regresses into a glorification of the old, innocent days populated by imaginary, Disneyfied versions of indigenous peoples”.

Documenta gGmbh could hold off most of these attacks until the Taring Padi incident, which breached their defences on the battle lines of the public media relations. That incident effectively granted a duplicitous “I told you so” victory to the far-right.

It is of course possible that Taring Padi—understanding their work to have no antisemitic intent and expecting the permissive cosmopolitanism of global contemporary art—understood the problematic configuration of antisemitic figures in the People’s Justice. Sophisticated public statements by Taring Padi, ruangrupa, and art historians Wulan Dirgantoro and Elly Kent suggest that the antisemitic motif and its complex history was well understood. Perhaps they believed that freedom of artistic expression would triumph. They wouldn’t be the first. Anselm Kiefer’s 1969 Sieg Heil performance in Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) rings a bell. Perhaps it was Taring Padi’s misunderstanding of European universal freedom of expression, not of antisemitism, that was exposed.

Whatever the case, far from bringing a “particularism” of the Global South that conflicted with European universalism, Taring Padi has laid bare a universalism more universal than German society is able to accommodate. Now it is German society that calls on one of the tenets of so-called post-colonial discourse to its defence. As Steyerl writes, and as Meron Mendel (Director of the Educational Institution Anne Frank) has repeated: “everything must be locally situated and historically contextualized”—by which they mean, in the German context. Representing a kind of secession from the cosmopolitan worldview, documenta fifteen has thus become perhaps the first documenta to truly take place “in” Germany, as opposed to in the universal, contextless tabula rasa typical of global contemporary art exhibitions.

But the debate about censorship misses the point. To keep the banner on public display risked offending the hearts-and-minds spirit of ruangrupa’s documenta, which explains why both ruangrupa and Taring Padi willingly removed it. Such internalised self-censorship, a common practice in institutions today, is evident as well in The Black Archives at the Fridericianum, where words and figures are censored (in the manner I am about to do) in racist representations of so-called H*******ot.

On the weekend, Mendel withdrew his offer of support to documenta gGmbh. He had been approached by director Sabine Schormann at the outset of the scandal to assist auditing works. Then she appeared to backdown. Mendel claimed neo-colonialism and accused documenta gGmbh of treating ruangrupa like children: “When I organised the (Antisemitism in the Arts) panel discussion, I really wanted to invite ruangrupa. But Schormann said: No! We cannot do that to them, they will be overwhelmed”. Steyerl, who has had a line of communication with Mendel, quickly followed suit, withdrawing her work from the exhibition.

Both Mendel and Steyerl ignore the possibility that the artists in documenta fifteen do not wish to engage in a process that would grant Mendel—no matter the terms of his involvement—an incontestable mandate down a slippery slope of further interference. Perhaps they are more concerned about physical safety, especially those artists living in the Fridericianum and especially following the likes of Party Office whose members have been subject to anti-trans vilification, and some of whom have now fled Kassel. For some participants, the environment that has encroached upon documenta fifteen is one thing: unsafe.

The possibility of dialogue

“I have no faith in the organisation’s ability to mediate and translate complexity”, said Steyerl when she demanded her work be removed from documenta fifteen. Unfortunately, she did not say what complexity requires to take place.

It is hard to ignore the undeniable parallel (and undeniable differences) between the offensive display of antisemitic caricatures at documenta fifteen and the proposed exhibition of Santiago Sierra’s offensive Union Flag work at Dark Mofo at MoNA in 2021. A public outcry and a powerful media campaign shut down that work. But despite public support from figures as senior as Michael Mansell, who asked the organisers “to ensure that the free flow of ideas prevails over short-sighted censorship”, and private support from several high-profile Indigenous artists and activists, MoNA was unable to formulate in compelling terms a complex public discussion on the subject. All they could shout over radio-waves was “freedom of expression!”

Is documenta gGmbh’s apparent inability to formulate complexity in the public debate about documenta fifteen a fault of the individual occupants of the offices of the organisation, or an effect of the institutional form itself—as if complexity cannot be articulated in this way? At the opening media conference of documenta fifteen, Schormann in gleeful affirmation shouted “You all rock!”

The position of ruangrupa is no easier. While defenders of community (that organic formation of people outside the strictures of societal institutions), they too are de facto occupants of an impersonal office of German civil society as the “curator” appointed by documenta gGmbh. That much was confirmed when one of ruangrupa’s founding members, Ade Darmawan, appeared last week before a committee of the Bundestag. ruangrupa have also been reduced to the position of defending documenta fifteen mediated by the institutional form of the documenta organisation.

Too bad. Anyone who visits documenta fifteen to see for themselves will discover that it stands in stark contrast to its reflection across the forums of civil society (mainstream and social media, press releases, parliament, etc.), as if it exists in a parallel reality. Does art not belong in the middle of society after all?

It’s a shame Steyerl pulled out. It wasn’t only a slap in the face of the other artists but her work about a “quantum shepherd”, stinky bacteria-based “cheesecoin”, and the decelerationism of capital also made good fun of crypto and NFT bros. It brought a healthy sense of self-deprecation and humour to the exhibition.

But focussing on individual works of art in this way misses the point. Documenta fifteen is supposed to be about a process of doing, making, sharing, living, healing, surviving (choose your own doing word) that will last 100 days for the public and no doubt longer than that for the artists who are building new possibilities of creating together right now.

Ultimately, like Enwezor’s documenta11, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. This documenta will be judged on its idea, which with the smallest prick created a huge controversy revealing the bad conscience of Germany: both its failure to be free of its Eurocentrism and its failure to be free in its guilt.

Special thanks to my mum, Karin Lettau, for the many valuable discussions when we visited documenta together and for correcting my German.

Paris Lettau is a contributing editor at Memo.