Exhibition view, Dhuluny: the war that never ended, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 6 July – 8 September 2024. Photo: Silversalt Photography

Dhuluny: The War That Never Ended

Anastasia Murney

Inside the gallery, there is a desk mounted to the wall. It is made from polished red cedar, fitted with short, ornate legs. The desk is chipped in a few places but is otherwise in good condition. On the promotional material for Dhuluny: The War that Never Ended, the desk is bathed in red light, creating a sinister effect. In the exhibition, it’s installed in conjunction with a series of photographs. Each one stages the desk against a different backdrop in Bathurst—outside the wrought iron gates and stone pillars of the Bathurst Court House, on a manicured lawn in front of a grand Victorian-style mansion, under the patio of the local bowling club, and on the ceremonial grounds of the Wahluu, otherwise known as Mount Panorama. In this last photograph, the desk sits atop the entire township of Bathurst; it’s a striking nighttime scene with a ribbon of orange tinging the horizon. The figure of Wirribee Aunty Leanna Carr is woven through the photographs, moving between the foreground and the background, wearing a possum skin cloak. She designed these photographs in collaboration with Henry Simmons, capturing scenes where colonial violence was enacted in the past, and is still being enacted in the present. In doing so, she reveals Bathurst as one big massacre site.

The desk is understood to be Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s transportable writing desk, moving with him from Sydney to Bathurst. He wrote innumerable deeds and legal documents from this desk, producing devastating and far-reaching ramifications for First Nations people across what is now known as New South Wales and Tasmania. It is a potent symbol for the translation of words into actions, and the extent to which those actions are protected under the rule of law. Curated by Carr and Wiradyuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones, Dhuluny: The War that Never Ended is a significant, multi-layered exhibition at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery commemorating the two hundredth anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in Bathurst on 14 August 1824. This laid the groundwork for the indiscriminate killing of Wiradyuri people with little to no legal repercussions. The title of the exhibition comes from local Elder and traditional owner Dinawan Uncle Bill Allen. Dhuluny (pronounced “dhu-loin”) is the Wiradyuri word for “truth,” “rightness,” and “gospel.”

Dhuluny: the war that never ended, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 6 July – 8 September 2024, featuring Wirribee Leanna Carr, Bangayadilinya, 2024, digital prints on Ilford paper, Red cedar clerk’s desk from the Museum Collection of Bathurst District Historical Society. Photo: Silversalt Photography.

In Stephen Gapp’s Gudyarra, a book on the Frontier Wars in Bathurst, he shatters the idea that Wiradyuri people were “wandering bands who attacked Europeans as opportunities arose,” detailing how warriors such as Windradyne led a fierce and co-ordinated campaign against the colonists. According to Uncle Bill Allen, this part of Wiradyuri land was a well-known warrior training ground. In the exhibition, colonial artist John William Lewin’s colour engraving is believed to be a portrait of Windradyne, a man with curling, silver hair and a short beard, wrapped in a fur-lined possum skin cloak. However, Carr and Jones are cognisant of the masculine bias framing these events on both sides, eclipsing the stories of women. In the photographs surrounding Macquarie’s desk, Carr is a figure that shifts in and out of focus; sometimes she is visible, other times she is hidden in the landscape. In Gapp’s book, he describes how women were present in battles, they would tend to the wounded, send smoke signals and gather information. And yet we don’t know their names.

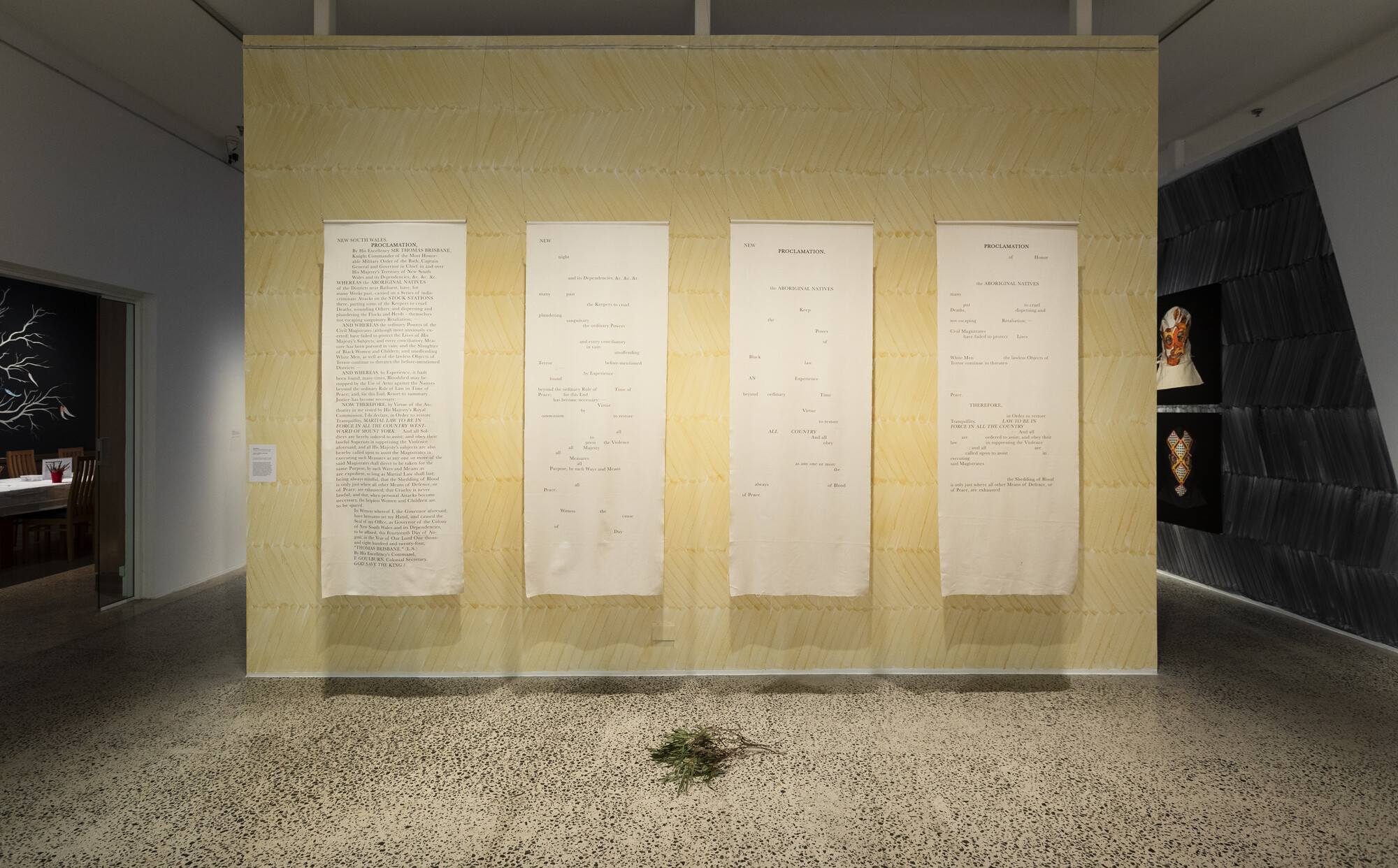

In Dhuluny: The War that Never Ended, Carr and Jones place contemporary Wiradyuri women artists in the centre. Among them are the charismatic sculptures of Karla Dickens and Lorraine Connelly-Northey, both of whom rework colonial detritus in their practice. Dickens uses carnivalesque kitsch and popular culture while Connelly-Northey draws on farming materials, such as barbed wire and corrugated iron. Jazz Money contributes a poetic response to the original declaration of Martial Law. She translates the text into three large calico columns, erasing certain words and phrases to unwrap the euphemistic language of state-sanctioned violence. Across from this artwork, Aunty Lucy Williams-Connelly (Connelly-Northey’s mother) exhibits a series of dillybags, clustered together in a row of bright red, yellow, and black yarn. The white walls of the gallery are textured with ochre and charcoal patterns, signifying healing, sorry business and protection; this creates a rippling effect from room to room.

Installation view, Dhuluny: the war that never ended, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 6 July – 8 September 2024, featuring Jazz Money, remains of context, 2024, inkjet on calico. Courtesy the artist and The Commercial Gallery. Commission by Bathurst Regional Art Gallery. Photo: Silversalt Photography

In the foyer, Jamie-Lea Trindall’s budhangbu gidharrabu (blak gold) (2024) offers another set of vessels: lustrous black ceramic objects, gilded with linear and diamond patterns. The vessels are made from the blackest clay available. Each one is about the size and shape of an item belonging to a tea set, exhibited in individual glass cases. Trindall’s work expresses a tension between different methods of engaging with the land. On the one hand, the technique of gold lustring speaks to the onset of the Gold Rush in the 1850s, a few decades after the declaration of Martial Law, where hopeful diggers travelled deeper into rural areas in order to extract a new resource from the ground. Ceramics, on the other hand, is closer to Wiradyuri practice of heating the earth to cook with, meaning the women who have used clay ovens to make bread for thousands of years. The recurrence of coolamons—shallow vessels for holding things—in the exhibition reminds me of Ursula Le Guin’s 1986 essay subscribing to Elizabeth Fisher’s Carrier Bag Theory of human evolution, suggesting the first cultural device was a recipient of some kind, not a bone or a weapon. Le Guin uses this to subvert the narrative model that places the hero (and his weapon) on a pedestal. What happens if we tell stories through bags, nets, and vessels instead of muskets and spears?

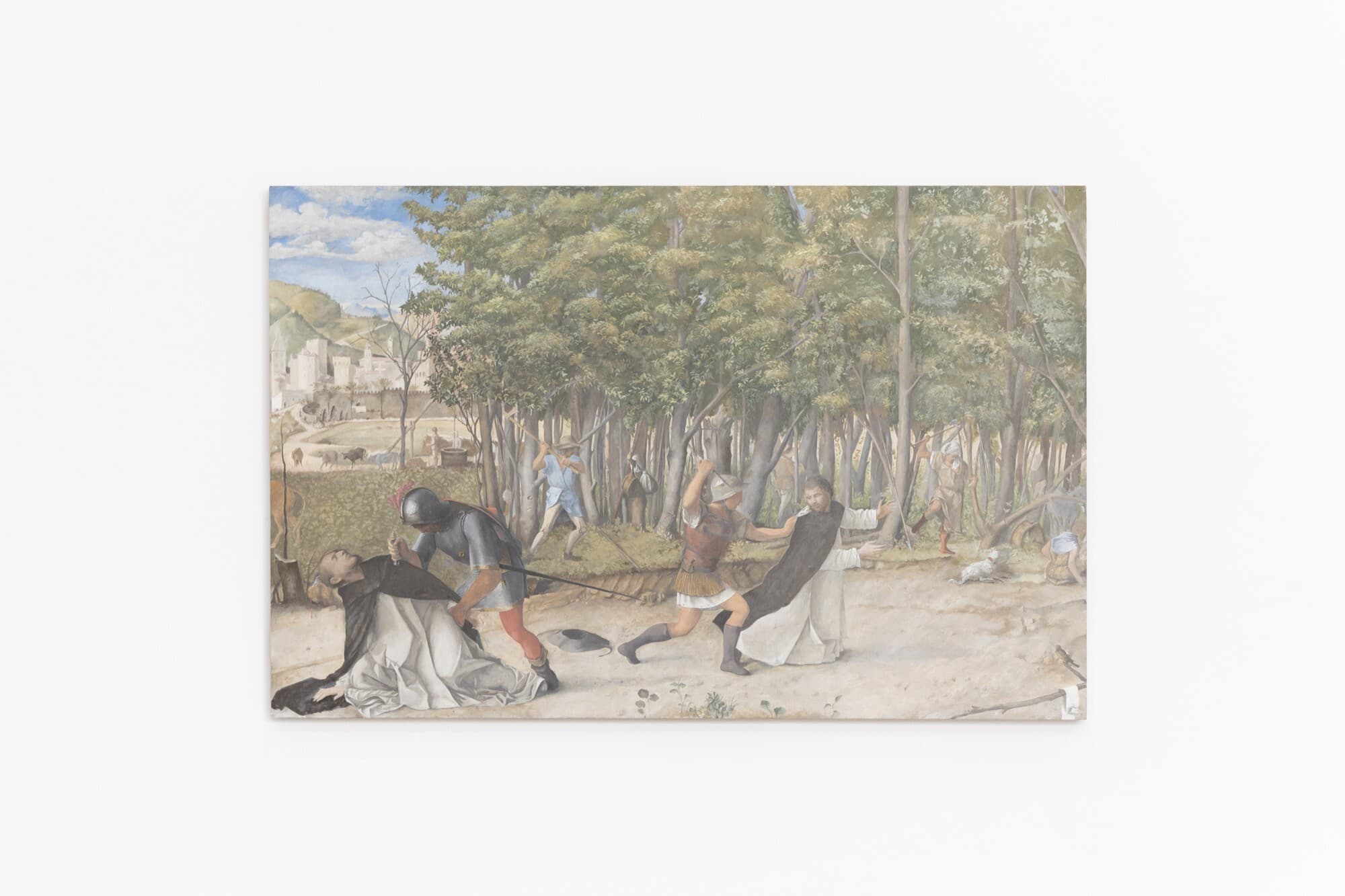

Another layer of the exhibition includes a selection of artworks from an earlier generation of Wiradyuri artists active from the 60s through to the 90s. Michael Riley’s Flyblown (1998) comprises large-scale conceptual photographs, a companion series to his film, Empire (1997). Storm clouds, ethereal and menacing crucifixes, and dead galahs on cracked earth reflects the rapacious violence of settler-colonialism. In the colourful acrylic paintings of HJ Wedge, he mourns the loss of native birds and wildlife as a direct consequence of the genocide extending west. All of these Wiradyuri artists are juxtaposed with the work of two colonial artists, John William Lewin and Augustus Earle, whose paintings and engravings record the expansion of settler presence in Bathurst. Lewin was the first official artist of the colony of New South Wales, accompanying Macquarie on his 1815 expedition, while Earle was a leading watercolourist at the time.

Installation view, Dhuluny: the war that never ended, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 6 July – 8 September 2024, featuring Lorraine Connelly-Northey, Possum-skin cloaks: Waradgerie Winnowers, 2024, rusted iron and tin, barbed wire, and wire. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Silversalt Photography

In the middle of the gallery, Earle’s painting Bathurst Plains and Settlement. New South Wales, ca 1825–1828 sits adjacent to Connelly-Northey’s Possum-skin cloaks: Waradgerie Winnowers (2024), six large sculptural pieces, arranging torn, aged, and rusted tin with coils of wire. Loaned from the State Library of NSW, the painting is an idyllic scene, depicting a land of gentle, rolling hills, fertile soil and open space. In the background, there is a smattering of houses and an emerging row of fences demarcating the seizure of land. Connelly-Northey’s work speaks back to the smooth surface of Earle’s painting, drawing attention to the violence of turning land into an exclusive (white) possession and expressing the rough edges of settler-colonial placemaking.

There are spaces for settler contributions to truth-telling in Dhuluny: The War that Never Ended. These are some of the more eclectic inclusions. In one of the first rooms, Something Happened Here (2023) is a collaborative pedagogical project between artists, teachers, and students. A compilation of videos features local children from different schools in Bathurst re-enacting episodes from the Frontier Wars. One such episode is referred to as ‘the Potato field incident’, where a settler offered potatoes to a group of Wiradyuri people, who later returned to help themselves to the crop. The settler fired on them, resulting in a massacre. Watching the videos, I remember being a child of about ten and being tasked with making an advertisement for my hometown. I and a few classmates put our heads together and came up with some ‘facts’ about the place where we grew up. The short video, recorded on a 90s VHS camcorder, was mostly centred around Ben Hall the bushranger, a figure who looms large over the town. As Carr remarked at a panel discussion after opening night, this is the first generation who will know the truth about what happened here.

Exhibition view, Dhuluny: the war that never ended, Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 6 July – 8 September 2024, featuring Unknown Ancestors, Stone tools, pre-invasion, stone. Collection of the Bathurst District Historical Society. Photo: Silversalt Photography.

In another part of the gallery, there is a collection of stone tools from unknown Wiradyuri ancestors, loaned from the Bathurst District Society. Percy Gresser, a retired shearer and amateur archaeologist, collected over 6000 tools in his lifetime. The tools in the exhibition are carefully framed and annotated in his neat, looping handwriting. And echoing across multiple rooms is the voice of David Suttor, reading the diaries of his ancestor William Suttor, who was an ally of the Wiradyuri people. These contributions speak to the responsibilities settlers have in relearning, preserving, and upholding a true account of what happened in Bathurst. On this note, an important part of the exhibition is a comprehensive public program that will take place in August: conferences, workshops, performances, and film screenings that will centre truth-telling and celebrate the survival of Wiradyuri people.

As I sit on the XPT, slowly winding through the Blue Mountains, it strikes me that I am retracing the route taken by colonists in the early 1800s. Perhaps the militarised outposts dotted through the mountains are the same as the train stations we stop at. Forbes, the town I grew up in, was a product of the Gold Rush, inseparable from the extractivist impulse to mine and create wealth to be distributed amongst settlers. My father was raised in Cowra, where he crossed paths with HJ ‘Harry’ Wedge at Cadet training. I look up the site of the old Erambie mission and realise I have passed this location in a car countless times. I remember, with a jolt, what Wattle Flats looked like when I passed through it a few years ago. There is a place near here that was known as ‘murdering hut’, where poisoned dampers were left out for Wiradyuri people to eat. In a few weeks’ time, I will drive out to Mudgee, and wonder about the location of the Suttor’s farm, where William Suttor first met Windradyne. And of course, I grew up going to Bathurst for eisteddfods, concerts, sports, and shopping, not knowing this is a land soaked in blood. This is part of the work of truth-telling, moving beyond ignorance and denial, into a fuller account of what happened here.

Anastasia Murney is a writer and teacher living on Gadigal land. She holds a PhD from the University of New South Wales