Data Relations

Audrey Pfister

Facing the usual difficulty of how to begin writing, I ask ChatGPT for advice on reviewing ACCA’s exhibition Data Relations. I ask: what would you write? ChatGPT suggests this:

As we navigate an increasingly digital world, where does humanity end and technology begin? The exhibition Data Relations at the Museum of Contemporary Art (sic) explores this question through the work of several cutting-edge artists who use data as a medium to question our relationship with technology … Data Relations offers a thought-provoking look at the blurred lines between the digital and the physical. This show is not to be missed for anyone interested in the intersection of art and technology.

It’s cliché. Chances are if you’ve been online in any kind of subcultural or youthful space you would have noticed that “the intersection of art and technology” (not to mention “liminal space”) has become a bit of a meme. Since ChatGPT is trained, in part, on an enormous amount of data scraped from the internet, what ChatGPT tells us is indicative of a popular discourse. “The intersection of art and technology” and the “blurred lines between digital and physical” are repeated dichotomies, buzzword refrains and vaguery now devoid of meaning. I was eager to see Data Relations—its line-up features artists I’ve long admired—but I was concerned that the curatorial framing would slip into the buzzy territory ChatGPT demonstrates.

Curated by Miriam Kelly with assistance from Shelley McSpedden, the exhibition includes expansive works by Zach Blas, Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, Lauren Lee McCarthy, Machine Listening (Sean Dockray, James Parker, and Joel Stern), Mimi Ọnụọha, and Winnie Soon.

To accompany the exhibition room sheet, Kelly asked each artist to answer the question “What is Data”? Machine Listening provides a key proposition: “Data isn’t mined, it’s made.” This position pushes against the Big Tech rhetoric that data is the “new oil.” Importantly, Machine Listening is reminding us that data isn’t a raw resource plucked from nowhere. Instead, data is always partial and always conditioned. If we take seriously what ChatGPT wrote, that data is the medium these artists use, then perhaps we can better think beyond just what data is, and ask questions around what data is doing materially, ideologically, structurally, relationally.

Tucked away in a small room in the middle of ACCA is Machine Listening’s installation After Words (2022). The work is an eight-channel, fifteen-minute audio work consisting of a dimly lit room, a procession of chairs where the audience can sit and listen, and an accompanying transcript outside the room, pinned to the wall. In the arts we often talk about artworks that invert the (male, colonial, western) gaze, but curiously, After Words inverts the ear. Instead of algorithmic “smart” devices such as Amazon Echo or Google Home listening to us, After Words compels us to listen to the computational. Machine Listening probe us to consider the epistemic and linguistic shift towards what writer Kate Crawford has called “Big Data fundamentalism.” How do rapidly expanding language model machine learning tools (such as ChatGPT, which fortuitously premiered the same month Data Relations opened) change the way we see and know the world?

To visualise this question, the artwork plays with theatrical conventions. After Words is a semi-fictional restaging of the development of an Emotional Speech Dataset at a research centre in Toronto. We’re confronted with the uncanny speech of various actors trying to capture emotions in words for the purpose of building the dataset. In audio samples we hear actors “emotionally” reading the words “wake,” “word,” “sarcastically,” and “voice.” Listeners are ushered into the convoluted web of actors, and classification processes involved in dataset production. Early in the audio, a voiceover asks us to imagine a computational dataset “of a million voices. Imagine that a hundred thousand of these have been tagged “unhappy.” Imagine the Amazon Turk worker paid a few cents an hour to do this tagging. Imagine Jeff Bezos on a yacht. Imagine the neural net running twenty-four hours a day. Imagine its energy consumption. Imagine a computer made of humans.” After Words broadens our scope and reminds us that data is made not a neutral or natural resource to be mined from nowhere and everywhere. Machine Listening reminds us that algorithmic technologies rely on much the same thing as theatre: code, actors, and performance. Datasets aren’t raw, neutral, naturally occurring resources but rich, elaborate productions.

Next to After words is Blas’s installation Tales from a Stony Troll and the Shady Mystics of Silicon Valley (2022). The work is in another dimly lit room, but this time the space is illuminated with an ultraviolet light, and the floor is marked with a fluorescent green vinyl circular sigil and a scrying plinth. There are three large video projections on the wall. The central projection is orb-shaped and displays an animated troll’s face—if the aesthetics of mysticism feel both cryptic and comical that is precisely the point. Playing with the Silicon Valley ideologies of magical thinking, Tales from a Stony Troll attempts to make obvious how Big Tech rhetoric often purposefully obscures notions of power, wealth, and control.

The figure of the troll not only references internet trolling and the practice’s links to the alt-right. Importantly, the troll and the orb also reference The Lord of the Rings, a point of inspiration for the big data company Palantir co-founded by conservative, libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel. A palantíri is a crystal stone used in The Lord of the Rings for god-like surveillance or wisdom. It isn’t the first example of a Tech Giant founder being inspired by sci-fi or fantasy literature. Tales from a Stony Troll nods not just to the present but also the history of Silicon Valley birthed from 1960s counterculture and libertarian ideologies and economics—see Ayn Rand. It’s an important historical line for Blas to trace. Mainstream commentators tend to treat Big Tech figures as Thiel, Elon Musk, and Mark Zuckerberg as mere oddballs, failing to address the ideological lineages that foster and reproduce these power formations in the first place.

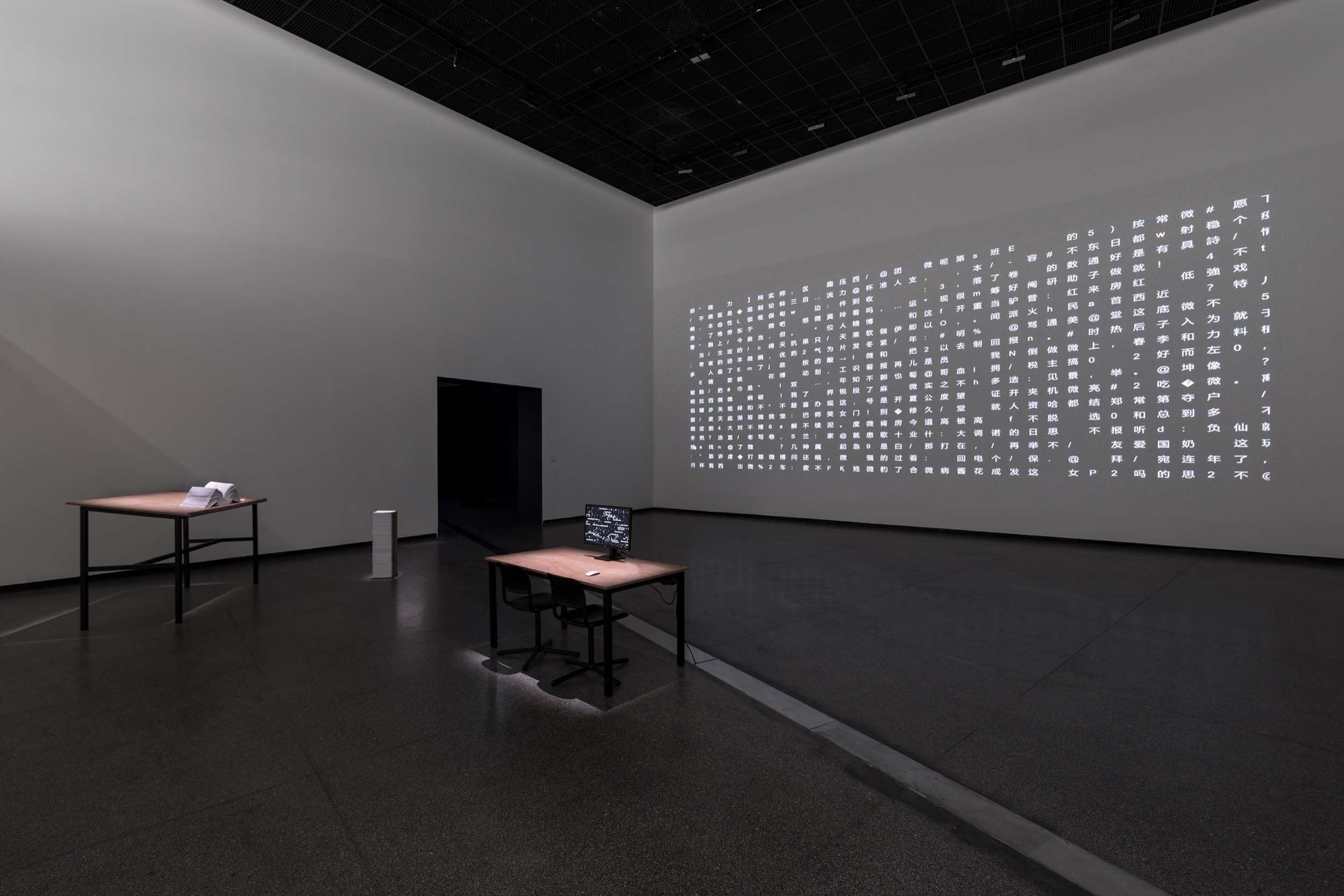

Less academic and more comical, camp, colourful, and intriguing, Tales from a Stony Troll comes as a relief midway through Data Relations, after viewing Machine Listening, Soon, and McCarthy’s more cerebral and dense contributions. Soon gives us Unerasable Characters II (2022), a ridiculously oversized 2,652-page book and large black and white text projection spawned from her custom software built to visualise tweets erased from Chinese Weibo. The main takeaway? The sheer glut of data and censorship and the absurdity of content moderation bots. McCarthy’s eclectic installation Surrogate (2022) considers how rapidly developing reproductive technologies shape our outlook on human life. While the adjacent videos, LAUREN (2017–ongoing), show the artist acting as Alexa, the smart assistant, by remotely observing real-life participants and regulating conditions in their homes.

The next installation I encounter is Synthetic Messenger (2021) by Tega Brain and Sam Lavigne, a pair known for their collaborative projects involving data scraping, language processing, and digital high jinks. Synthetic Messenger consists of twenty TV screens clustered in the centre of a room, screening videos of an animated hand scrolling news articles related to climate change. The index finger on the screen would click on the various online ads that ran alongside the articles. Yet this wasn’t just an animation but also screen recordings from actual bots that the duo created with the intention of increasing the value of climate change–related media.

Synthetic Messenger reveals the logics of contemporary news cycle media as advertising revenue driven and broadens the Overton window for how we can think about online activism. That said, Synthetic Messenger felt underwhelming in comparison to something Brain and Lavigne describe as a “digital guerrilla intervention” and an attempt to “geo-engineer” the news. Not to be the “Yet you participate in society. Curious!” meme guy, but referring to Synthetic Messenger as a form of climate activist geo-engineering feels dissonant when we consider the sheer amount of energy required to power the bots in the first place, or the TV screens for the months the exhibition runs.

This is not meant to discredit Brain and Lavigne’s work. Rather, it explains how my understanding of their practice shifted once I started to consider it in terms of the phenomenon of “astroturfing” (the political or corporate technique of creating a false impression of “grassroots” support). Reading Synthetic Messenger as a form of astroturfing not only yokes nicely with the crowded materiality of the screen display in the gallery but also helps us recognise how an individual’s data, for example, isn’t in itself useful to Big Tech companies. Only when data becomes collected en masse as a crowd of behavioural patterns does it become a useful resource to capitalise on.

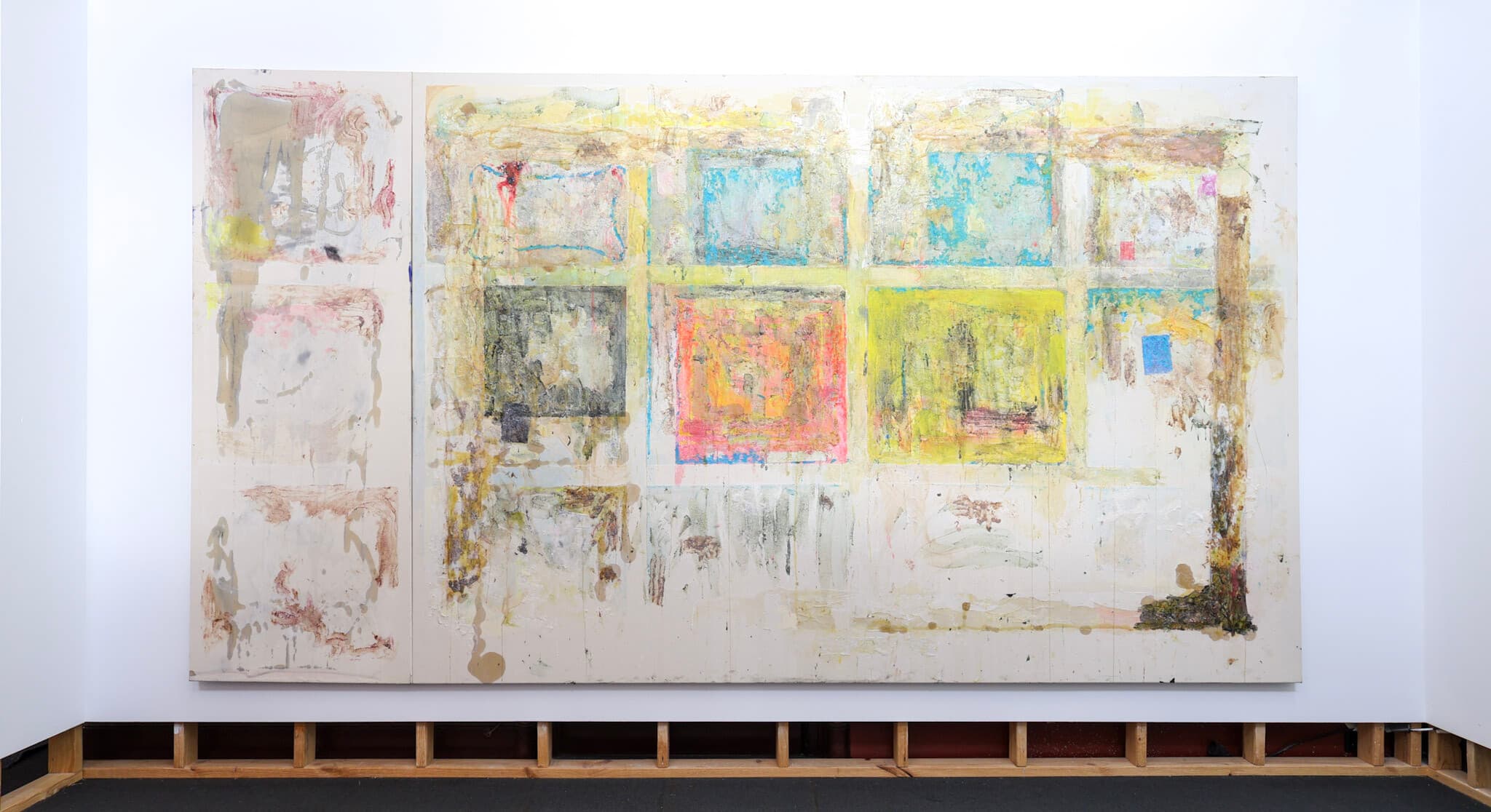

An installation that has grown on me since leaving the exhibition is Ọnụọha’s These Networks in Our Skin (2021) and The Cloth in the Cable (2022), situated in the final room at ACCA. Stretching across the length of the wall, These Networks in our Skin is a single-channel video where close-up shots of hands cutting, weaving, tying, and lacing hair, fabric, and computer cables—fashioning these materials into new open-ended objects and infusing them with soil and spices. The Cloth in the Cable is one example of what these embellished woven computer cable textile objects can look like and was created in collaboration with British-Nigerian-Australian designer Dinzi Amobi. The work sweeps from the floor and up the length of the gallery wall. Ọnụọha unpicks the notion that there can be neutral, unbiased technologies. She impresses us with an understanding that we shape, co-evolve with, and are defined through techno-social infrastructures, and that we might refashion these infrastructures to better reflect and service everyone.

While the exhibition is overtly didactic, critical data discourse really shone in the more pedagogical Data Relations Summer School. The distinction is subtle but significant. Joel Stern and James Parker of Machine Listening collaborated with ACCA to curate a four-day long program of discussions, experimental workshops, talks by academics and artists, and performances related to critical data studies, data scraping, machine vision, language automation, what could be called Net and Post-Internet related art, and more. Participants ranged from PhD candidates, casualised lecturers, indie game developers, digital artists, sound artists, art theory grads, and curators. Through participant-led discussions, experimental exercises on listening and reading, and rigorous artist/academic Q&As, the program expanded and shifted the curatorial focus of Data Relations away from a narrow focus simply on the what of data. But maybe I’m just always going to be someone who gets off on lectures, set readings, and discussions more than I do on capital-A Art.

To me, some of the most compelling work and crucial conversations of Data Relations were presented on the final day of Summer School by a collective of artists and researchers from Capture All. The collective emerged from a collaboration between Naarm’s experimental sound organisation, Liquid Architecture, and the Delhi-based platform for information, urbanism, media, and infrastructure studies, the Sarai Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. Joel Sherwood Spring, a Wiradjuri artist based on Gadigal and Wangal lands in the Eora Nation and member of Capture All, spoke about his work DIGGERMODE, which I had viewed earlier down the road at ACMI’s exhibition How I See It: Blak Art and Film where it was screening. It was a work that actually hits; the kind of work I wanted to see in Data Relations.

DIGGERMODE pans across the shots of land, sand dunes, data visualised hills, open pit mines, film archives, state police dancing to TikToks and proposes that “attempts to measure this immeasurable landscape/ Are the origins of property.” The film urges us to ask key questions: What digital and material sites are we extracting from? Who is doing the extracting? What are we capturing? Categorising? Archiving? Governing? And what are we placing value in? Spring asks us how minerals, spaces, and materials contain memories of Country. Consider sand; consider how it is used to make silicon microchips. Consider lithium; consider how it is extracted to make batteries; consider the labour relations to make batteries, consider the material flows of data storage, consider the communities being dispossessed and land torn apart by (data-) mining operations locally and globally.

Spring’s presentation and the questions it posed at the Summer School immediately grounded us in the material, locational, and geo-social—something quietly missing from Data Relations. But summer has finally come to an end. The clouds are back today, and I think of all our data circulating up there, in the other “cloud.” It’s cloudy trying to picture all these relations refracting everywhere, massive networks of information, minerals, and labour. When looking up, we have to remember to look and ground down too.

Audrey Pfister (sometimes-) writes, edits, and works in the arts and is currently based in Naarm. They have a Bachelor of Art Theory and First Class Honours in Arts (Media, Culture, Technology). You can usually find Audrey in the library.