HIBALL, installation view: Composition for Mnemosyne, 2024. Two-channel 2k video, stereo sound, 7:24 min. Photo: Ben Adams. Courtesy the artists.

Data Minds

Hilary Thurlow

Over the last decade or so there’s been a not-so-subtle uptick in exhibitions detailing our online infrastructure. Leading the pack was Electronic Superhighway (2016–1966) at Whitechapel Gallery in London, curated by Omar Kholeif and eponymously named after a term coined by proto-media artist, Naim June Paik in 1974. From documentation alone, the exhibition seems groundbreaking, capturing the teleological development of computers and the internet through practice. Although everyone I’ve met who saw the show has emphatically relayed how it was “terrible” and “ghastly” for framing technology as yet another -ism and for how little reference there was to exhibitions that had come before, namely Software in 1970. At the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Kholeif had another go with I Was Raised on the Internet in 2018, albeit with a slightly different framework—zoning in on how the internet has shaped our world.

Closer to home, machine learning and artificial intelligence have come to the exhibition-making fore. UQ Art Museum ran two exhibitions under the autological title of Conflict in My Outlook, curated by Anna Briers—one online (We Met Online, 2020–2022) and one IRL (Don’t Be Evil, 2021–2022). Then in 2022, ACCA devised their own take on tech’s impact on our relations interpersonal and otherwise with Data Relations. The following year, Artlink’s After AI issue was published. Fast-forwarding to this year, Artspace and MCA have both scheduled exhibitions geared toward the topic. I know there’s a myriad of shows and editorials missing from my list, but you get the gist. Even W.J.T. Mitchell is slated to publish a book on AI in the near future. His work aims to trace a genealogy of the technology beginning with psychiatry and the 1956 Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence and going all the way to LLMs like ChatGPT. It’s buzzy, it transforms STEM into STEAM, and it meets funding bodies at the “intersection of art and technology.”

Yet, when these kinds of exhibitions are placed next to the more tactile work of engineers or developers and product owners, who work in the coal mines of Appen and Palantir, the art begins to look less like piercing cultural commentary and more art-y. Working as an artificial intelligence engineer wasn’t even cool until OpenAI released ChatGPT in late 2022. Although glib of me to generalise—because of course, there are exceptions to every rule—these exhibitions, especially those I’ve listed, up and down the east coast, only argue in polemics. Big data is bad. AI is worse. Will it replace artists, or won’t it? It’s all so apocalypse now. And, of course, with Silicon Valley infiltrating the oval office ,it’s easier than ever to lean into whatever tech-inflected polemic we’re handed. Perhaps the antidote to this polemic isn’t resistance or antithesis, but a kind of ambiguity.

Enter Data Minds, curated by Wednesday Sutherland with Alexandra Kirwood at the Lock-Up in Newcastle. The exhibition offers up a suite of works that detail how “in the post-industrial era, our increasing reliance on the Internet, and new developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI), continue to reshape our perception.” Or alternatively how burgeoning technologies have altered our social worlds. Here you won’t find anecdotal facts about how ChatGPT takes 519 millilitres of water (slightly more than a standard water bottle) to write a single 100-word email (although I’m telling you now). Or how in late 2024 a Democratic political consultant was fined six million US dollars by the United States’ Federal Communications Commission for commissioning one of the more notorious Biden deepfakes.

HIBALL, installation view: Composition for Mnemosyne, 2024. Two-channel 2k video, stereo sound, 7:24 min. Photo: Ben Adams. Courtesy the artists.

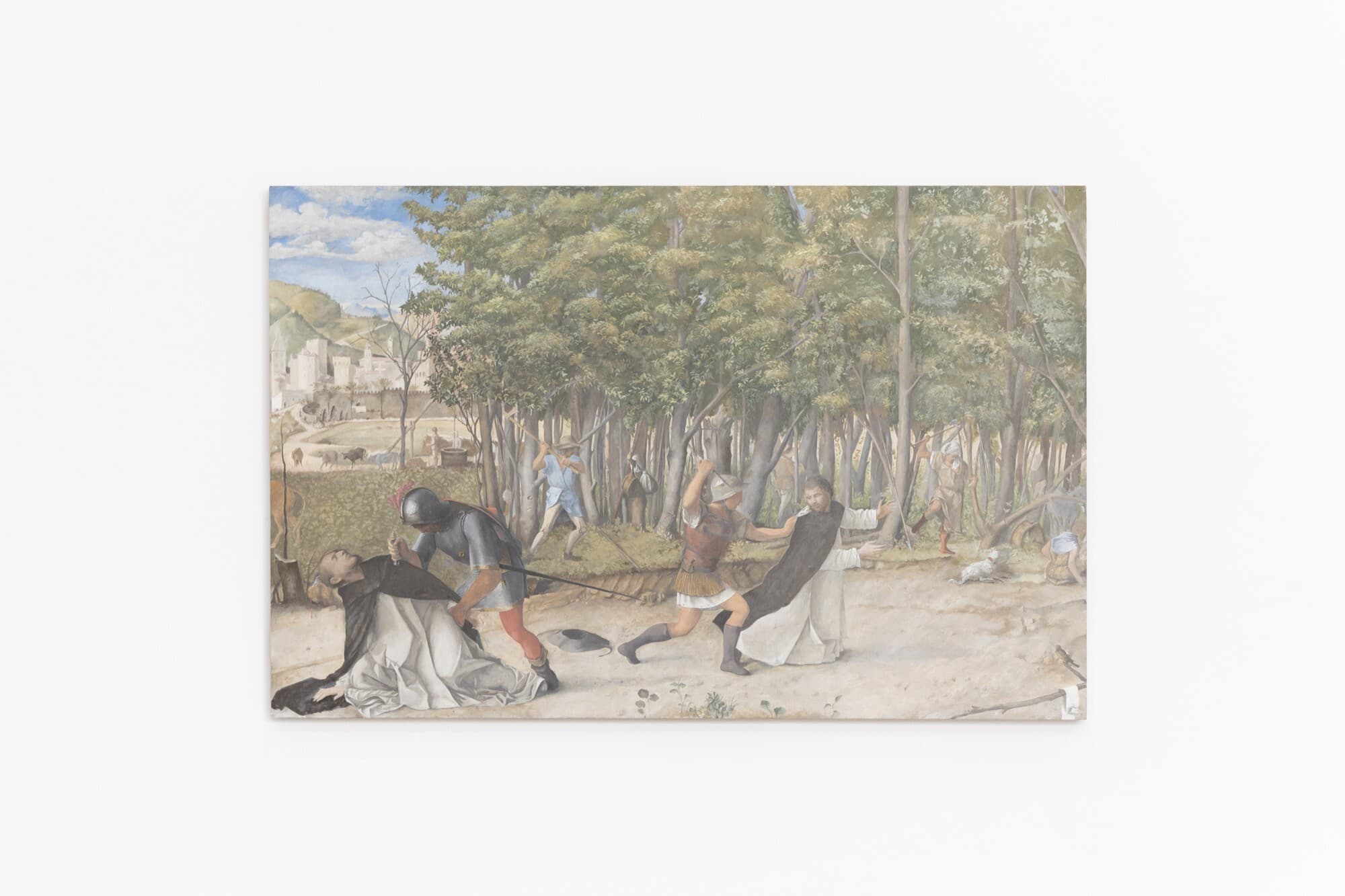

Collaborative practice HIBALL—comprised of Stanton Cornish-Ward and Alexandra Kirwood—developed their two-channel video work titled Composition for Mnemosyne and five accompanying wall works during a prior residency at the Lock-Up in 2024. Commissioned for Data Minds, their two-channel video is easily the focal point and linchpin of the entire show. Mnemosyne oscillates between the quaint technologies and infrastructure that have spurred the steel city’s economy forward and the immaterial (yet tangible) impact of burgeoning AI-driven systems.

One channel captures The Hunter Singers, a Newcastle youth choir directed by Kim Sutherland OAM and conducted by Charissa Ferguson. The choir perform a score generated from various AI fragments that long-time collaborator of the artists, Mitchell Mackintosh, has turned into sheet music for the choir to perform. The other channel juxtaposes a group of teenagers moving through Newcastle’s outskirts: remnants of WWII encampments and barracks; a fighter jet museum; the omnipresence of Australia’s main F-35 training base—one of Australia’s most AI advanced artillery that passes through Newcastle’s sky daily. Funnily enough, the opening was filled with members of the community who were all enthralled with seeing Newcastle’s outskirts on the big screen. Although easy to do so, HIBALL never offer a judgement call on whether these advances are good or bad as that would be too didactic. Instead, the narrative if left open.

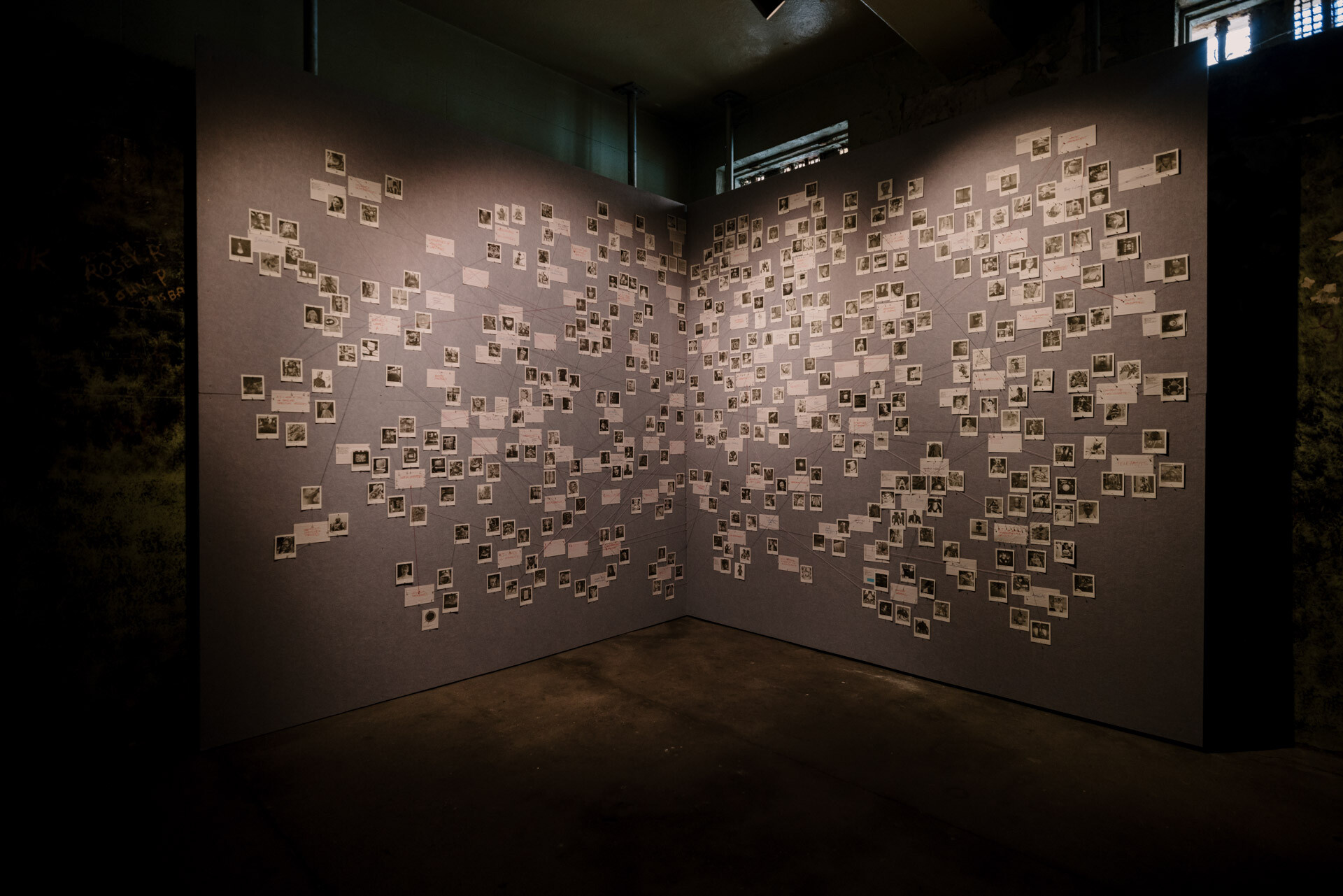

Roy Ananda, Evidence wall, 2023. Digital prints and ink on paper, thread, pins, acoustic pinboard, dimensions variable. Photo: Ben Adams. Courtesy the artist and Artlink

In another area of the Lock-Up, Roy Ananda’s Evidence wall (2023) offered a more materially informed, analogue take. Originally commissioned for Artlink’s AI issue, the wall is akin to an evidence board in a TV crime show. Across two pinboards, Ananda has connected over four hundred “fictional automatons, robots, and artificial intelligences (AIs).” Think the Marvel character H.E.R.B.I.E, R2-D2 and Red Dwarf’s Kryten, each printed to mimic a polaroid with their name written in pencil below their image. The AIs are grouped (strun together) by an array of pathologies, whether megalomania or sadism, as well as, in some cases, their Myers-Briggs. Ananda shows us that the fear (or excitement) toward our near-robotic future isn’t alien or new, but has haunted pop-culture since its dawn.

Jon Rafman, Punctured Sky, 2021. 4K video, stereo sound, 21:09 min. © Jon Rafman. Courtesy the artist, Neon Parc and Sprueth Magers

Also led with humour is Jon Rafman’s post-internet-y video Punctured Sky (2021). Although Rafman has the highest profile of the artists in the show(AM1) , the star power of his work is minimised when placed in dialogue with his co-stars. Nonetheless his video in search for a false memory of a childhood video game played after school reminds us how the internet isn’t forever. Taking notes from “hardboiled” crime fiction, the video’s gamer protagonist retraces his cyber past and in turn reveals how the humble home PC can mediate our inner and public lives. Two of Rafman’s paintings from his debut show at Naarm’s Neon Parc are on display too, Panic on the Beach (2023) and Riot in the Mall Parking Lot (2023). Taking their cues from the image diffusion model Midjourney, these paintings are weird. You could think of them as holding the same aura as early DALL-E images with figures that appear normal at first glance becoming disfigured with a longer gaze.

Brie Trenerry, Trip Code V.A.L.I.S, 2024. HD AI Generated Video, colour, sound, polystyrene, paint, 11:22 mins. Runway ML Gen 3 Alpha/Turbo. Photo: Ben Adams. Courtesy the artist and MARS Gallery.

The Lock-Up’s former life as a police station and holding cell for short-term prisoners is integrated into Brie Trenerry’s—who taught both members of HIBALL at RMIT—work, which is spread across three of the remaining cells and is in the former exercise yard. Titled Trip Code, the body of work mediates “history, technology and psychological control.” Most memorable was V.A.L.I.S. (Vast Active Living Intelligence System) (2024), a work that utilises AI to render thousands of hallucinogenic videos largely drawn from cinema that were then trawled through and then stitched together by Trenerry. The video’s content digitally rebuilds the Lock-Up’s cells and loosely follows “Stacey,” a sexualised muscle mummy who mutates from a goat (a Severance spoiler?) and is modelled on a character in Ana Lily Amirpour’s The Bad Batch (2016). V.A.L.I.S. is everything far/alt-right all at once. References to WWG1WGA or QAnon snake across the screen as do tropes from Piero Pasolini’s Salò (1975) and red-pill culture. We’re imprisoned by a panopticon of our own making, our screens.

Girl On Road, dirtstyle: cipher, 2024. Dirt, Apple Mac Mini, python script, petrichor, sound, dimensions variable. Photo: Ben Adams. Courtesy the artist

In the cells over from Trenerry’s Trip Code is Girl On Road’s (Matilda Sutherland) dirtstyle: cipher (2024) and dirtstyle: bit plane 5 (2024). Cipher speculates what would happen if we were only able to communicate through image encryption and rendering the algorithm a critical tool for communication. Coded in the programming language Python, the work takes shape as ever evolving bit planes, which draw from a media library (films, iPhone images, web content, etc). This content concurrently atrophies and reassembles, producing a greyscale of distorted pixels before our eyes. Sitting below the monitor is a pile of dirt smelling of petrichor, reminding us of where and how the material world touches that of the digital.

dirtstyle alsoreminds us that new-fangled technologies in our everyday lives tend to follow a peak-to-trough ratio of short-lived excitement, followed by a flatlining of banality. We could perhaps think of a more practical application—away from art—the start-up app Doji. Still in beta, the app uses five photos to build an uncanny valley AI avatar (albeit thinner and hotter) for you to try on clothing from high-end retail sites like SSENSE and Farfetch.

The diatribe pushed onto AI, machine learning, etc. too often evades nuance. These new(ish) applications of technology are either an existential threat to our very humanity or an opportunity of boundless potential. These binaries have not led to much good. The nature of big tech isn’t necessarily something we should (or need) to run to and catastrophise but instead is something we should live with in spaces of ambiguity. Embracing ambiguity shouldn’t be confused for indifference or apathy, but instead allows us to move through the grey space without levelling our curiosities. At the beginning of this review, I flippantly mentioned Software, an exhibition at the Jewish Museum, Brooklyn, in 1970. The show, radical for its time (and likely still to this day), was curious as to how technology would shift human communication, and ambiguous in levelling any kind of judgement too. Data Minds picks up this same sort of ambiguous curiosity.

Hilary Thurlow is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.