Dale Harding: Through a lens of visitation

Hilary Thurlow

Dale Harding: Through a lens of visitation at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA) draws out the strength of matriarchal lines within Dale Harding’s artistic and cultural practices, giving space for knowledge-sharing and making to his mother and other significant matriarchs, established and emerging. Curated by Hannah Mathews, Through a lens of visitation incorporates works by Dale and Kate Harding, Dale’s mother and an artist in her own right. By way of his matrilineal line, Dale is of the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples of central Queensland and his work centres on the culturally and artistically significant Carnarvon Gorge and surrounding Country. More than just the clichéd connections drawn between textiles, women and feminism, intergenerational feminisms echo throughout. Dale shares gallery space and collaborates with his mother Kate, as well as educator Jan Oliver and his cousin Hayley Matthews. Many themes are articulated across the body of work shown in Through a lens of visitation, but the main focus is upon the intersections between the history of Australian art, minimalism and matrilineal lines.

Through a lens of visitation has wriggled out from between two distinct categories in art history in Australia—that of Australian art on one hand and Aboriginal art on the other. It crosses dialogues and points us to where paths of modernism and late modernism intersect with the sacred and sublime site that is Carnarvon Gorge. Dale is not providing a critique of these intersecting moments in history but, instead, points toward them as a shared and warranted happening: moments pregnant with opportunities for dialogue. Mike Parr’s time in Central Queensland and search for The Gorge is documented in Dale’s To appropriation, solidarity & dialogues (2017), a framed work comprising six images. The title alone underscores Dale’s ambitious and powerful framework, where interactions such as Parr’s—however naïve or possibly uncomfortable—are not burnt on the pile of history but are instead allowed to sit within the cultural history of The Gorge.

To strike-out such attempts from the record under the guise of rejecting cultural appropriation would have a silencing effect on this cultural history, echoing the suppressions brought about by colonial power. The image of Parr is from his work Identification no. 1 (Rib markings in the Carnarvon Ranges, North-West Queensland) (1975/1999) and appears alongside Dale’s photographs of early “tourist art” works by Richard Bell that were made for punters on the Gold Coast wanting a slice of Aboriginal art. Also placed in the frame is a sheet of photographic paper brushed with Reckitt’s Blue and an image of red ochre extracted from Dale’s grandmother’s Country. This is a complex work and in a way acts as an index of a theme in Dale’s practice and this exhibition. The titular “appropriation” is not an accusation but is, rather, an avenue to acknowledge shared histories between white Australia and its Traditional Owners that are too often told separately. As Ian Burn stated in 1983 when writing about the display of Aboriginal art at the National Gallery of Australia, one history cannot exist without the other. And it is messy, but potent.

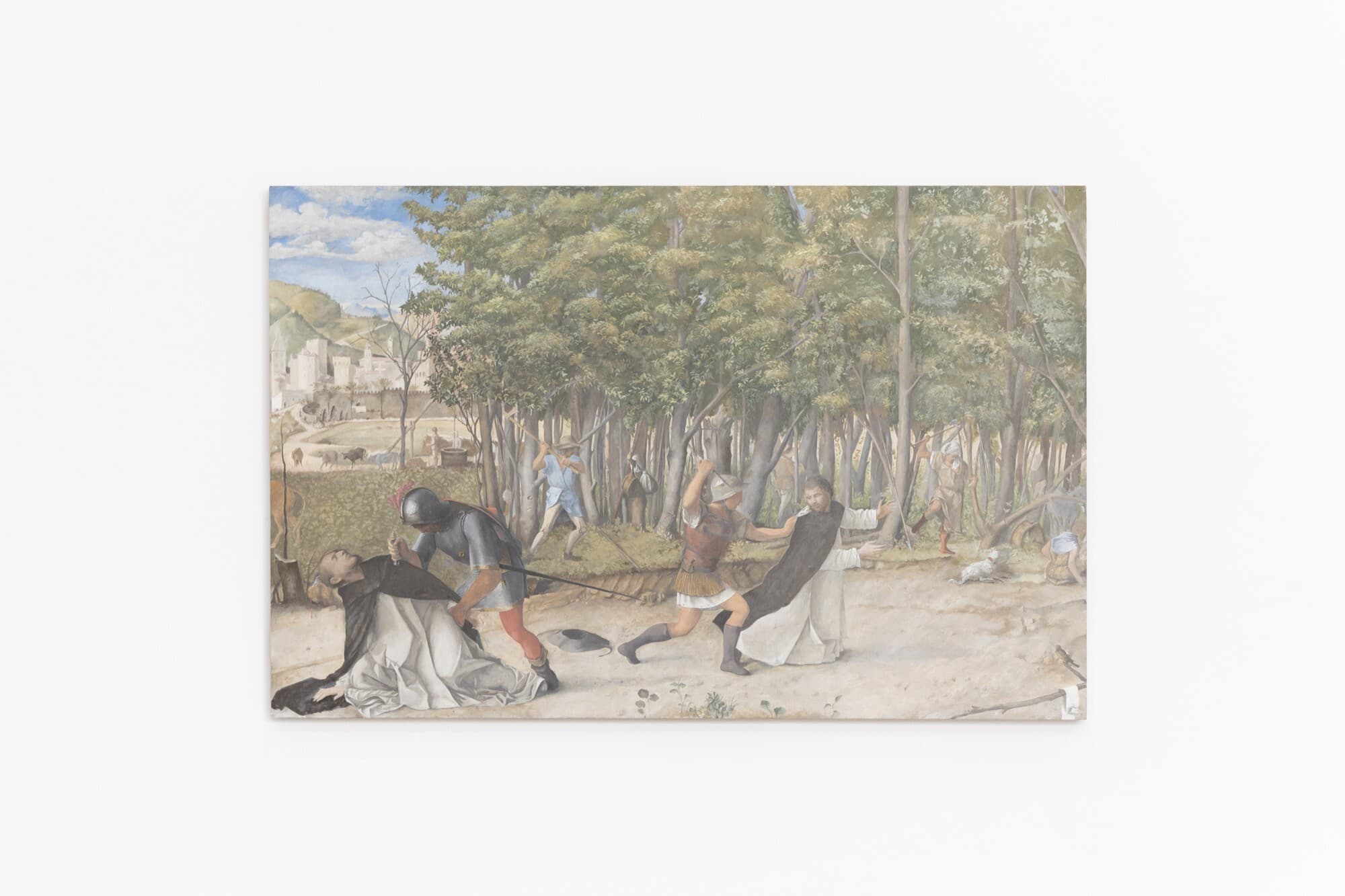

Rather improbably, Sidney Nolan and Margaret Preston also visited The Gorge, seeking to untap its “primordial” feeling. Preston, as recognised by Gordon Bennett, had begun to think through the gesture of a singular “national art” as one that would inherently need to be cross-cultural. Nolan’s photographs from his trip to The Gorge, following Preston’s exact itinerary, are referenced in Extractive Painting 2 (2021). A powerful manoeuvre by Dale—in this work and many others—is that of concealing. In particular, Extractive Painting 2 is turned face-first against the wall, exposing only the back of the stretched canvas. Beside it, however, are sheets of photographic paper (referencing Nolan’s photographs) which are painted with ochre scraped from the surface of the adjacent painting. At once we are seeing both sides: closure and disclosure. This technique is very important in its relation to cultural safety—of defined epistemic boundaries that govern cultural knowledge and protocols that surround who is and who is not permitted to see and to know. I am reminded of a tongue-in-cheek yet telling piece of museology put forward by Dale at his 2019 IMA exhibition: on a floor-line cordoning off a sculpture were the words “You are welcome to not enter”. In the present work and other concealed works this gesture reappears: we are not ignored and turned away, but recognised and invited not to enter as active participants in a process of cultural ignorance.

Layered into such weighty gestures is a phenomenological inclination, which plays out in particular with Dale and his cousin Hayley Matthew’s Untitled (private painting H1) (2019), a work developed over seven days and commissioned for the Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates. Hayley’s story is told across each panel and has been deliberately concealed beneath diaphanous layers of white paint. Covering provides an element of cultural safety. Yet, as more time is spent in front of the panels, motifs and language become visible. Patience is key. It is also key to being participant in a dialogue such as the one that Hayley and Dale have created: the more time you spend listening and looking the more you will appreciate the potential beauty of engaging without extractive expectations. New expectations around viewership are apparent here, thereby tempering existing lines in the sand. A parallel is easily drawn to the employment of Aṉangu language in the work of Kunmanara Mumu Mike Williams: many viewers might not understand, but perhaps direct extractive cognisance is not the point—something more interesting is going on in these works. For Untitled (private painting H1), too much focus on finding the hidden meaning in Hayley’s story will mean you ignore the painting in its own right as a painting and ignore the new questions being asked of you.

Acacia gum on glass (2021) shares a phenomenological resonance with the painter Robert Hunter’s wall paintings, which Dale installed alongside Hunter at Milani Gallery in 2011. For Acacia gum on glass Dale has painted one of the gallery windows with a milky brown acacia gum (gum arabic) and hematite, clouding the view beyond the gallery. This proposes the space as a sacred site, similar to how stained-glass windows denote Christian architecture. At the same time, Dale’s queer body is indexed onto a separate panel of glass leant up against the window—an extension of his wall paintings and those on the rockface at The Gorge. Each contributor’s body is registered to the rock face by way of the size of their hands or the tools they’re stencilling with corresponding to the size of their body. Here, the sheet of glass is cut to Dale’s height, 201cm, providing a similar body index. Again, Dale indexes his body in Moonda and the Shame Fella (2018). Here, two lengths of glass—one wrapped in toxic yet protective lead, and the other glowing as light hits its sheen of orange xanthorrhoea (grass tree) resin—sit on a plinth just too small to hold them.

Again, connections can be easily drawn to post-minimalist art: Roni Horn, Eva Hesse. The deliberate employment of this minimalist aesthetic is a powerful connection between Western art history and the way that rock art is experienced at The Gorge. The phenomenological registers are similar: seeing the indexed stencils of human bodies from other times causes you to imagine the rest of their body, who the painters were, standing in this same spot at this exact wall. Both in minimalism and rock art there is a deeper awareness of materiality, objecthood and our own physicality. With Dale’s works, convergence of these histories is a remarkable achievement conceptually, culturally and artistically.

Dale’s work with Reckitt’s Blue—an ultramarine pigment likened to that made famous by Yves Klein and used to brighten and whiten laundry by domestic servants—takes on a lesser role in this exhibition than it has previously in his practice, though it is highlighted by two works made with the last of the artists’ Reckitt’s supply: What is theirs is ours now (I do not claim to own) (2018) and Blue ground/dissociative (2017). The works mark a resuscitation of the past and an exploration and telling of forgotten and hidden histories of the artist’s matrilineal line. In doing so they reposition the misogynies of male colonial-settler anthropologists who sought to record the voices of patriarchs. Dale’s grandmother and great-grandmother all worked in forms of domestic servitude under the coloniser’s squattocracy.

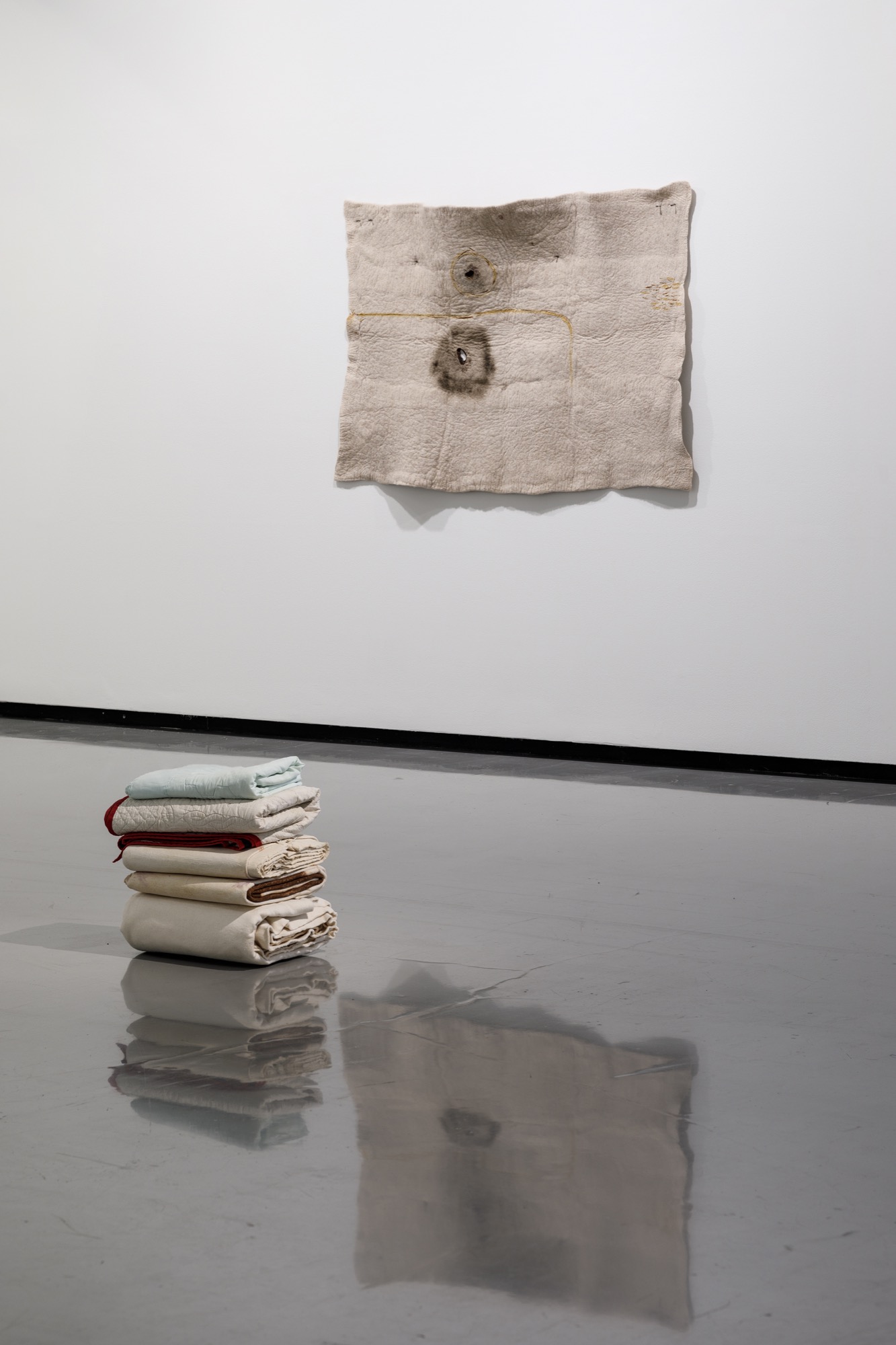

Kate’s quilts articulate how intergenerational knowledge is passed down from mother to child. This knowledge is seen most clearly in the stack of blankets Birth and ten-year-old-quilts (2021) by Kate, as well as Dale’s Cloaks (mortua and mortuus) (2018), Repression cloak (ceremony for a gay wedding) (2018) and Untitled cloak (2018)—one of the more pointedly queer works in the exhibition. Analogous to the work of Félix González-Torres, there is a poetic sensibility and a degree of what cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz has identified in queer and racial minorities as “disidentification” as Dale “tactically and simultaneously works on, with, and against, a cultural form”—in this case, less “against” as an opposition and more as a productive friction.

The strata of blankets is like the rings of a tree, marking Dale’s growth while couched solidly in the warmth and security of the mother. Again, however, we are invited not to enter: the quilts and blankets are folded neatly and their designs are tucked away. Kate’s quilts also demonstrate a preoccupation with materiality evident in Dale’s work: Carnarvon (2020) includes fabrics dyed in ochre washes, bringing Country with it. Hanging delicately from the surface of this work is an array of tiny, intricately woven pityuri bags, highlighting Kate’s mastery of these cultural forms. The form of the quilt is a potent symbol, emphasising the work Aboriginal women were required to do as domestic servants: sewing, repairing clothes, doing laundry. Kate’s reclamation of this symbol offers a reclamation of these very histories, much like Dale’s reclamation of the histories of artist visitations to The Gorge.

A different kind of maternal kinship is realised through Dale’s work with former Queensland College of Art tutor, Jan Oliver: a matriarch in her own right within the art school. As a gesture of utilitarianism and sharing knowledge in artistic practice Oliver has guided Dale on how to felt wool. In the works F2 (Mt Hetty fire viewed from Bandanna) 2020 and F1 (Saddler’s contract) (2020) the wool has become a surface and evidences a matrilineal connection to knowledge. This, alongside Dale’s work with his mother Kate, marks a turn back to working with textile and “craft”—an early trope in Dale’s practice and where he first found career momentum with bright eyed little dormitory girls (2013), featured in Glenn Barkley’s string theory: Focus on Australian contemporary art (2013) at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

Through a lens of visitation marks a shift over a four-year period of making. It explores, in depth, the pervasive and weighty role that matriarchal knowledge plays for Dale, both culturally and in his approach to art-making. Significant collaborations between family, friends and history have been made here, and these give way to a more nuanced politics and aesthetic. Through a lens of visitation is underscored by a feminist method and genuine interrogation of Australian art history and its unlikely connection to The Gorge—a sacred site for Dale and his matrilineal line.

Hilary Thurlow is an emerging curator and writer based in Narrm.