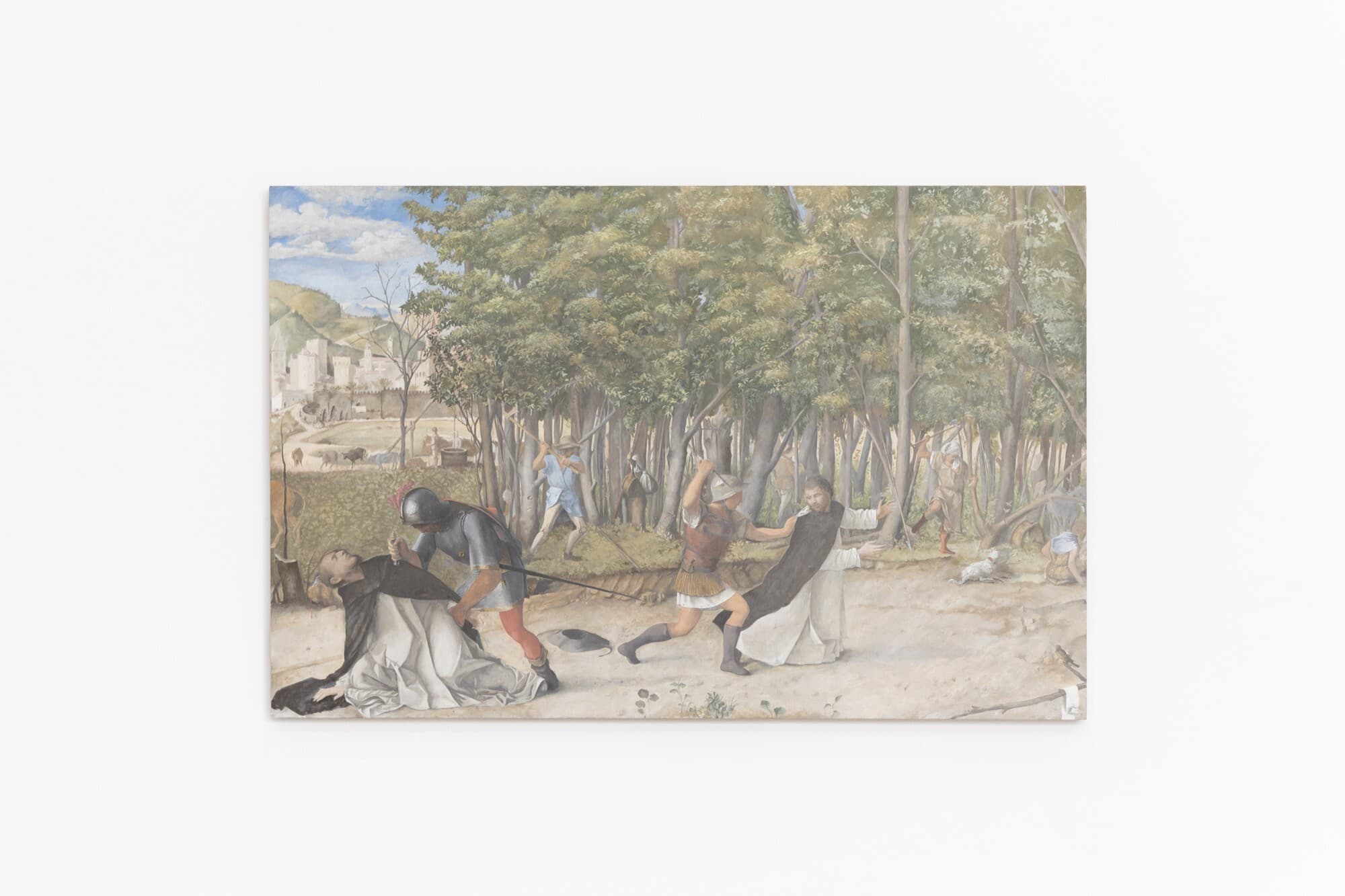

Still from Dale Frank—Nobody’s Sweetie, dir. Jenny Hicks, 2024. Courtesy of MIFF.

Dale Frank: Nobody’s Sweetie

Rex Butler

I think I’ve seen Geoff Newton sell a Dale Frank. It was at the recent Melbourne Art Fair. Neon Parc had three long walls of Frank paintings, made from putting various coloured pigments in resin and mixing them together, all extravagantly different yet somehow the same. A wealthy-looking middle-aged couple walked towards me—I was leaning down at the front of the booth carefully turning the pages of the massive newly-released Frank catalogue, some four-hundred pages long and a bargain at $220. They weren’t dressed particularly expensively or ostentatiously. The people who actually buy art rarely are. But you could just tell that they were wealthy and well-to-do.

The usually nonchalant and, let’s be frank, art-world indifferent Newton immediately stood up, suddenly erect and energised. He strode purposefully towards them with his thin new laptop under his arm. The woman soon disengaged and came over to look at the catalogue. But the man and Newton engaged in an animated discussion, with Newton periodically looking down at the computer screen and pointing. I presume they were discussing which one to buy and maybe even what price to pay for it.

Installation view of Dale Frank, Melbourne Art Fair, 2024. Image: Neon Parc.

I think the deal got done. Newton looked pleased. The man wandered over to join the woman, perhaps to figure out which room to hang the new Frank in. Meanwhile she had asked me who the artist was in the catalogue and I told her the same one who was on the walls. She didn’t appear to be as interested as the man. I can’t say I blame her. You’re either into art or not. It’d be pretty hard to convince somebody who wasn’t already interested that those shiny rebarbative surfaces, which distorted your appearance when you looked at them, were beautiful or significant or somehow made a difference to the world, although I spend my life trying to do so to rooms of young people. I guess once you’re in you’re in, as I realised when I caught a reflection of myself smiling at the whole scene in one of the paintings and felt no better or wiser than anyone else I saw reproduced there: Newton, his collectors, all the people walking past looking for a bargain or something to amuse them at the Melbourne Art Fair.

Last week at the Melbourne International Film Festival I saw Jenny Hicks’s 107-minute-long documentary on Frank, Nobody’s Sweetie. (The film’s title comes from a 2013 exhibition Frank held at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.) The film is mostly set on Frank’s extensive property just outside of Singleton in country New South Wales. It shows Frank roaming around the vast, mostly empty rooms with his only companion his dog, making work with a team of assistants, his extensive collection of taxidermied animals and his extraordinary garden project, for which he apparently can’t stop buying enormous palm trees from far-away places, transporting them on a truck and then hiring a bulldozer to plant them. We see him at his computer late at night poring over an intricate spreadsheet of works made and where they are to go, endlessly getting others to re-arrange the works on the wall for a show at Roslyn Oxley9, the opening night of the show, in which he has to mingle with the crowd, and his speaking of his recent diagnosis of autism, which he says explains his long-term difficulty interacting with people and retrospectively makes sense of much of his life.

Still from Dale Frank—Nobody’s Sweetie, dir. Jenny Hicks, 2024. Courtesy of MIFF.

We have interviews with his three principal art dealers: Geoff Newton of Neon Parc, Roslyn Oxley of Roslyn Oxley9, and his New Zealand dealer, Gary Langsford of Gow Langsford in Auckland. We have an interview with his chief studio and, we would suggest, life assistant, the recently returned soldier James Smith. And, of course, as with any documentary on an artist, there are the curators who have put Frank in shows and the critics who have written on him: Sue Cramer, who staged the exhibition Dale Frank: Twenty Years of Painting at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney in 2000; Edward Colless, who wrote “Dale Frank: A New Sorcery” for Art Collector in 2017; Memo’s own Amelia Winata, who wrote “Through a Glass Darkly: Dale Frank at Neon Parc” for Art Monthly in 2016; and the extraordinary Jane Rankin-Reid, threatening to steal the show, who wrote “Ticket to Ride: Dale Frank’s Conceptual Abstraction” for Art & Australia in 2004. I hope I haven’t forgotten anyone. I’ve only seen the film once.

But there’s one interesting thing about what they all say, or rather don’t say. They all speak in various ways about Frank the person: Colless calls him at once a “punk” and a “dandy” and Winata, perhaps most memorably, calls him a “likeable asshole.” However, as far as I can remember, no one speaks in any detail about the work. Of course, it’s shown throughout the film. We see Frank squirting gouts of coloured resin onto Perspex backing boards and his assistants then smearing them across the surface using blocks of wood following Frank’s brief instructions. We see the latest batch of paintings standing on the floor in Frank’s studio, then on the walls of Oxley’s gallery. We are given a brief survey of Frank’s back catalogue, from the performance pieces of the late ’70s to the pen and ink drawings of the ’80s to the first large-scale abstracts of the ’90s. But no one at any point attempts to tell us what this current batch of work—and there is an upcoming exhibition of it at Neon Parc on 30 August—actually says or means.

Still from Dale Frank—Nobody’s Sweetie, dir. Jenny Hicks, 2024. Courtesy of MIFF.

And it is at this point that Nobody’s Sweetie, which absolutely is quite enjoyable and successful as a film, gets interesting and perhaps revealing. For what can we say, or what indeed is left to say, about Frank’s recent work? One looks in the film at the speed, almost indifference, and the industrial scale with which it is made. But it is not in any way about this, as so much contemporary art is. One looks at Frank getting his assistants to re-arrange it, both in his studio and at Oxley’s, attempting to match up colours and patterns, and make the whole show “hang together,” but there’s not quite enough formal variety in the individual works for them to engage us in this way. (There’s a very revealing scene in the film where, just before the exhibition opens at Oxley’s, Oxley herself wants to take a painting out of the final hang and Frank wants it to remain and, indeed, I seem to remember, wants to include even more.)

The real enigma and interest of Frank’s work is why it is so successful, why so many people want to write about it, buy it, curate it into shows. I can’t for the life of me think why he, above so many other artists, has been chosen by critics, collectors, and curators to be the one. Or, to put it another way, his work functions as the test case for the arbitrariness of one particular artist being selected ahead of all the others. (It is this that each successive Frank show, which occur increasingly frequently nowadays, is about: it appears to take the place of all of the other artists who might be having one.) And all the terms critics use to describe his work in the absence of any proper art-historical contextualisation and evaluation—Frank is a “great” artist, his work is “avant-garde,” he breaks the “rules”—are just stand-ins for this success. What we now realise, and what Frank’s prominence tells us, is that all the usual criteria—aesthetic quality, critical self-reflexivity, even the artist’s identity and social representativeness—have been eaten up, have no real validity, at least in art, anymore.

Frank’s work—and his life in the film, characterised by constant back pain, eased by regular doses of alcohol and medicine—feels like the exhaustion of everything. Or maybe not exhaustion—because, as we see in the film, the artworld is never exhausted, even during COVID—but its opposite: a relentless, exhausting continuity with no real aim or purpose except to keep going. To keep on making, to keep on selling, to keep on living. But with no real purpose or explanation outside of itself. Maybe it’s what you’d call, in perhaps the real metaphor of the film, the autism of capitalism (but we might as well say the artworld): its blocking or doing away with anything outside of itself. It doesn’t know why it’s doing it anymore; it just keeps on doing it. (And for all of the potential provocation of saying this, we have to remember that Frank himself uses his neurodivergence as an explanation of his behaviour and the film itself, insofar as it is a work of art, necessarily makes of it something wider and more universal.)

But the fascinating thing, the empowering thing, the reason why we walk out of the film feeling somehow invigorated, is that Frank himself does not feel exhausted. He is relentless, unstoppable, ultimately unself-questioning. The beautiful final lines of the film are given in response to Hicks asking what Frank has learned as a result of his diagnosis, what lesson he might be said to have drawn from it. To which he replies: “To have the courage not to be hard on myself.” And Colless in maybe the most intelligent insight in the film says of Frank’s work that “it doesn’t take you into other worlds. It undoes this world.” However, we might suggest that it does not undo this world but precisely makes it, is the very emblem in its incessant production and appearance on gallery walls that there is only this world.

Still from Dale Frank—Nobody’s Sweetie, dir. Jenny Hicks, 2024. Courtesy of MIFF.

In a way, the odd thing about Frank is that he has made it so big as an artist without belonging to or being part of any artistic movement. Critics have tried, and even desultorily do so in the film—post-modernism, neo-expressionism, grunge, punk, expanded painting—but none really fit and certainly none of them even vaguely account for what he has been up to for the past twenty years. Nor can we convincingly suggest what time he belongs to or what moment is truly his own or that he embodies: ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, 2000s? But, in a way, after watching the film, we realise that he stands in for all artists in our current system, and indeed for all of us.

To repeat: Frank’s work is not about its selling, not about its commodification, not about the emptiness of the artworld and the exhaustion of its styles and meanings. It is too self-involved, too internally driven, too other-unaware for that. It is not ironic–and this lack of the typical get-out-of-jail-free card of much contemporary art is undoubtedly one of its strengths. It just is all of those things it appears to be. (And does anyone really believe for a moment that this irony in culture—which is what something like the Frankfurt School pinned its hopes on—is not totally commodified today?) It just keeps its head down while it drives over the cliff, like all of us.

And let us not be seen to be taking some higher moral ground here. There is none. We continue to file our reviews, publish our articles, stare at our computers filled with lists of things to do. We pour our earnings into something like Frank’s garden, hoping that it will outlive us, and even humanity, but knowing that it won’t. That’s why Frank in all of his weirdness, self-involvement, and lack of awareness of others is exactly like us and why we can identify with him so readily (and I realise I have just contradicted myself here). It’s why the film succeeds: not because it offers any explanation or justification of his art—there isn’t one to be had—but because we can see ourselves in it or at least its maker.

Still from Dale Frank—Nobody’s Sweetie, dir. Jenny Hicks, 2024. Courtesy of MIFF.

Hicks, who was an editor and sub-editor on a number of prominent fiction films before making this documentary, has invented a compelling new character in Nobody’s Sweetie. The film is all about Frank, not his art. And that’s undoubtedly why people are interested in his work, despite its mass production, the apparent indifference with which he makes it, and the inability of critics and commentators to offer any convincing explanation of it. It is because it is absolutely “autobiographical,” like buying a bit of Frank himself. The loneliness, isolation, and painfulness of his life, his drive to fulfil a goal that serves no purpose but will not stop, is like all of us. He needs to make art to survive, to eat, to pay his bills. It’s like any other job. That’s the finally moving thing about Nobody’s Sweetie: that we see ourselves in Frank. We too are nobody’s sweetie, just as Frank is everybody’s.

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.