Cressida Campbell, The path with rocks, 1989. Woodblock, painted in watercolour. Private collection. © Cressida Campbell. Image courtesy of Cressida Campbell and Warren Macris.

Cutting Through Time—Cressida Campbell, Margaret Preston, and the Japanese Print

Scott Robinson

A branch of wattle is nothing in itself…

— M. Barnard Eldershaw, Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, 1947

All the Portuguese merchants coming from Japan tell me that if I go there I shall do great service for God our Lord… for they are a very reasonable people.

— Francis Xavier, To His Companions Residing in Rome, 20 January 1548

Cressida Campbell and Margaret Preston’s relationship to the ukiyo-e tradition of Japanese print-making inhabit different artistic registers. Campbell’s complacent adoption of woodblocks and wholesale depiction of ukiyo-e prints affects the quality and significance of her work only indirectly. By contrast, Preston’s voracious cannibalisation of disparate materials serves, through force of will and artistic ingenuity, the coherence of her project. Cutting Through Time at Geelong Gallery suggests an attempt to locate Campbell in both a national and an international context, yet Campbell has persistently expressed ambivalence about the traditions imputed to her. The intention to use Japanese prints to connect Campbell and Preston disguises basic differences. Campbell retreats to interior spaces and art-market values, reflected by her retrograde uptake of woodblock techniques. Preston’s irrepressible aesthetic and technical liveliness internalise extraneous matter, like the ukiyo-e tradition as part of a historically vital public declaration.

Cutting Through Time—Cressida Campbell, Margaret Preston, and the Japanese Print, installation view, Geelong Gallery, 2024, Photographer: Andrew Curtis

Preston’s fulsome appropriation of print-making techniques and compositional principles is incorporated by what Bernard Smith called “her great independence of mind, volatile in temperament, ardently patriotic and consumed by a passion for experimenting in painting media and all kinds of graphic techniques.” Preston makes assertive use of her source material in ways that have productively challenged Australian artists since, whereas Campbell has received eerily little critical attention. Cutting Through Time can summon only superficial similarities. The conceit of cutting through time—with its evocation of gouging wood to make lasting images of ephemeral subjects—makes for a thin bridge connecting early modern print-making in Japan with Preston and Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Poppies 2005. Woodcut, printed in watercolour. Collection of Elizabeth Morton © Cressida Campbell. Image courtesy of Cressida Campbell and Warren Macris.

Cutting Through Time exhibits a selection of three distinct bodies of work by Campbell and Preston. The first room is reserved for Campbell with works drawn from the 1980s to 2022. A second, circular room displays several Japanese prints by masters of the genre such as Kitagawa Utamaro, Utagawa Hiroshige, and Katsushika Hokusai. These works span over a hundred years, from the late 17th century to the mid-nineteenth-century, though the aesthetic and cultural development of the practice is not emphasised in the display. This gives the impression of a unified tradition, despite the wide variation in style and subject between the prints. It implies a stable series of source materials for what would become Japonisme, although the European predilection for Japanese culture dates as far back as sixteenth-century Jesuit missionaries like Francis Xavier.

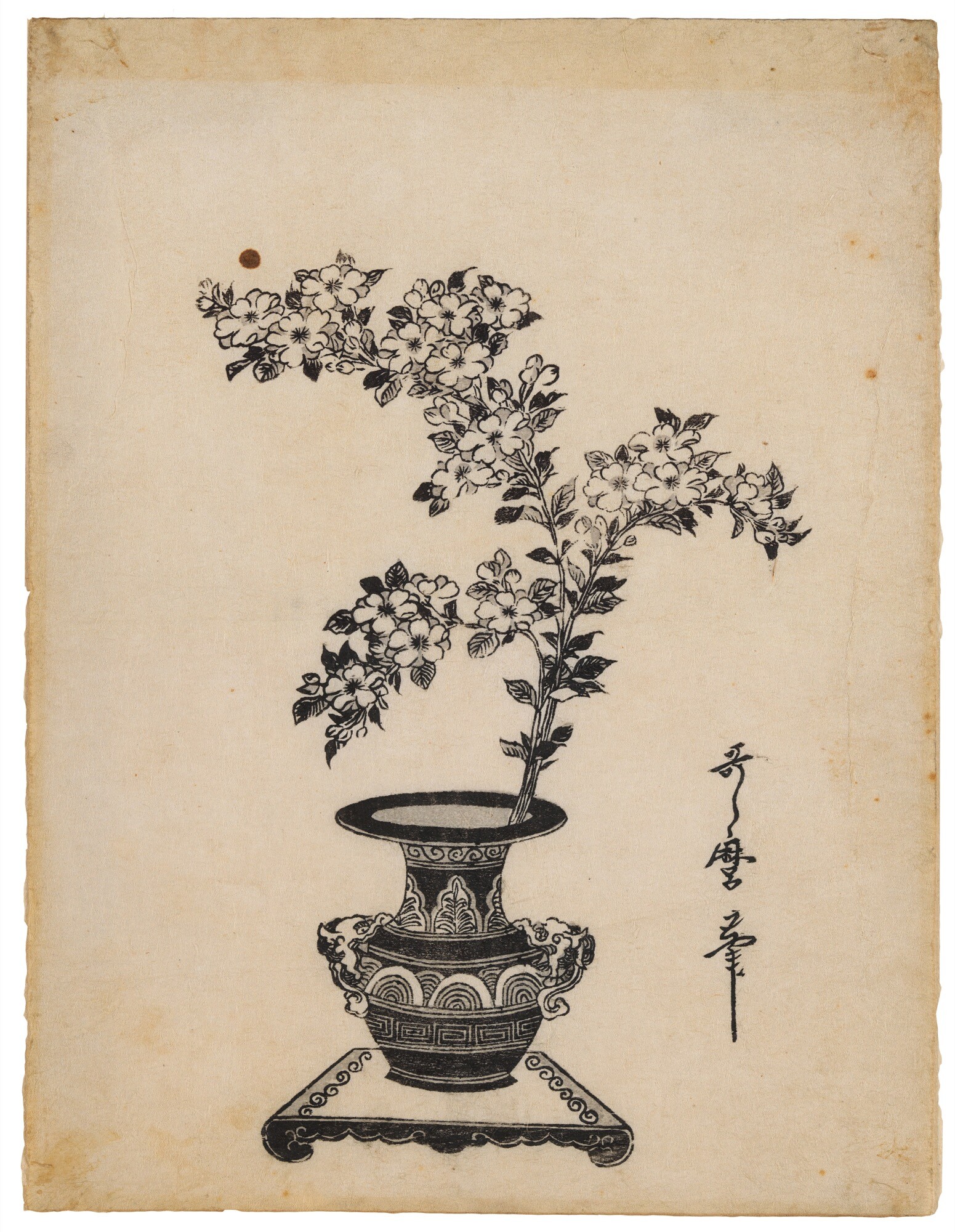

Kitagawa Utamaro, Cherry blossom in a two-handled bronze vase c. 1800–05. Woodblock print on paper. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Gift of Edmund Vardy 2001.

The final room expands laterally in a rough chronological order, Preston’s print works dating from her return to Australia around 1916 to 1957, near the end of her life. Preston returned from Europe with a project to adapt modernism for a national art. Having encountered Japanese prints throughout Europe, along with everything from Giotto to post-impressionism, Preston appropriated what she affirmed as “another quality to (my) realism—that of decoration.” Preston applied design and compositional devices stringently with what she calls “aesthetic feeling.” Her consistent experimentation baffled critics and peers (“Queer people,” she called them), though for Robert Hughes it was “owing to the popularity of her decorative flower pieces of 1921–6, which… never quite took on the solemnity of her vision, (that) Preston’s new work was swiftly accepted.”

The exhibition is designed to force the viewer to consider Campbell’s work of their own accord before moving to the contextual material of the prints and the far more luminous work of Preston. For its part, Campbell’s work likens some of Preston’s floral work to stained-glass. By contrast, Campbell’s own works have a papery quality, despite being thickly painted woodblocks, and her palate is muted and restrained. It is as if what Hughes surmised as the “umbrous gloom” of Preston’s early works transferred to Campbell. The dominant impression is of the ubiquitous “greige” of early twent-first-century suburban interior design—blandness dressed as calm neutrality. In her interview with Geelong Gallery’s Senior Curator, Lisa Sullivan, Campbell describes her pictures in the same terms paint companies like Dulux and Wattyl use to describe their undistinctive greige products: “calm” and “balance.” The colour appears designed to suggest nothing, not the blank unfinished quality of white but the absorbed stupor of affluent homeowners and real estate agents. It is a colour that proudly declares its lack of colour, vitality drained to an industrial norm. As Preston wrote in 1925, “the home is always a reflex of the people who live in it.”

Cressida Campbell, Journey around my room, 2019. Woodblock, painted in watercolour. Private collection. © Cressida Campbell. Image courtesy of Cressida Campbell and Warren Macris.

Preston’s decorative works are clearly intended to project an image outward, despite their “domestic” subject. They are intended to give interior spaces and magazines like The Home exuberance and beauty, conscripting them into the development of a collective national art. By contrast, Sullivan writes in her catalogue essay that Campbell’s paintings “invite viewers into the artist’s materially and aesthetically diverse domestic interior and private realm.” If Preston controversially appropriates design, aesthetic form and technique for a public project, Campbell placidly domesticates what she calls the “intriguing world of the Japanese people.” Journey around my room (2019) boasts Campbell’s personal collection of prints, ceramics, and furniture to the envy of many gallery viewers. Her works suggest homeliness in the same way an advertising image of a home suggests homeliness. The works flatter the cosmopolitan viewer with a safely aestheticised inflection of “other” cultures. They are decorated with bright vegetation while comfortably reposing in a scene that can be viewed, as Campbell avows, “almost like you’re walking past something.” This insubstantiality may be the “ineffable” identified by Miriam Cosic. The pictures are untaxing, and unlike Preston make very little overt claim on the viewer or the culture. Perhaps it is for this reason Campbell’s work has received very little critical attention prior to (and even following) her 2022 National Gallery of Australia retrospective.

Cressida Campbell, Gore Bay, Sydney, 1992. Woodblock, painted in watercolour. Private collection. © Cressida Campbell. Image courtesy of Cressida Campbell and Warren Macris.

The exterior landscapes in Campbell’s works are framed from within an interior space, like looking outward of a comfortably appointed Glebe or Pyrmont balcony. For instance, Through the windscreen (1986) cannily recuperates a semi-industrial landscape view to the comforts of the interior with the rear-view mirror reassuringly sealing the space off. Campbell interprets Japanese prints as investing “the outside world with an interesting and different sense of intimacy.” The trajectory of Campbell’s work presented in the exhibition demonstrates her work’s progressive retreat into controlled interior space. The interior spaces she depicts are not lived-in, but themselves pristinely decorative.

Katsushika Hokusai, Poem by Tenchi Tennō (c. 1835–36). Colour woodblock. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1909.

Preston, by contrast, extolled decoration as a way “to fill a certain space” rather than as a principle of life itself. Her work and biography suggest an artist constantly pushing outward, disseminating, encountering the cornucopia of the world and metabolising its vitality. Many of her floral works presented in Cutting Through Time are not a typical still life, nor depicted in the context of an interior setting. Preston writes in a letter of trying to “reduce my still-life to decorations,” finding it “fearfully difficult.” Instead, they are bold, heavy, and decorative in a manner that—like the ukiyo-e style—acknowledges their flatness. Works like Waratahs (1925) and Illawarra lilies and waratahs (1929) present flowers in their fulsome, voluble fleshiness. The thick red inflorescence of flowers that forms the distinctive waratah head are muscular and swollen in Preston’s thickly painted prints. In Fuchsia and balsam (1928), bright petals serve a compositional design clearly demarcated with thick black lines. Preston’s flowers are taken from the world and returned via the print, demanding the viewer to appreciate the particular beauty of Australian fauna.

Margaret Preston, Fuchsia and balsam, 1928. Hand-coloured woodcut. Geelong Gallery. Purchased 1982, © Margaret Preston/Copyright Agency.

The difference between Preston and Campbell is not a matter of topic, since both locate themselves within a “domestic” setting. It is a superficial link that, as Campbell suggests, “Preston influenced me when I was young… in her choice of subject matter.” It is in the style and approach to this topic that their divergences show. Campbell’s work terminates in its meticulous detail, whereas Preston argues and commands the viewer. Campbell finds her sources “All around her in the simple domestic life.” By contrast, Preston finds herself in “a mechanical age—a scientific one—highly civilised and unaesthetic.” For Campbell, the technology of printing itself is quietly negated in favour of bespoke editions, which Sullivan hails as of “equal significance” to Preston. This abrogation to the inherent reproducibility of the medium reflects a reactionary approach to the medium of woodblock printing.

Ukiyo-e woodblock printing developed as part of a burgeoning print culture in Japan, as Mae Anna Pang details in her essay for the catalogue. Prints of the “floating” or “fleeting” world (ukiyo) served an increasingly commercial, urban milieu, both commenting upon and reflecting the transience of fashionable pleasures and life itself. The vitality of the tradition was directly linked with the technological developments. “The woodblock prints of the Edo period emerged as a new kind of art that appealed to everyday people and were thus mass-produced for commercial consumption,” Pang writes. Preston’s appropriation of woodblock techniques embraces the possibilities of reproduction and commercial distribution as well as exploring the aesthetic possibilities of different methods and materials.

FJ Halmarick, Margaret Preston woodblock printing in Berowra, c1937. Copy print of a gelatin silver photograph. Margaret Preston archive, gift of William Preston 1963. National Art Archive, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Image © Art Gallery of New South Wales.

In “Woodblocking as a Craft,” a 1930 essay reprinted in the catalogue, Preston even promotes the accessibility of the technique, providing instructions while noting that

Australia is flooded with press-printed wood blocks. They are, from the craftsman’s point of view, almost valueless, having the same position that a hand-woven piece of tapestry has to a factory-made one. A craft is absolutely a matter of the hand and brain, and as soon as these partners are separated the result is incompleteness.

Preston recognises the specific economic conditions of artistic value and her work demonstrates the importance of “artistic feeling that the hand-done work retains,” while insisting that a print is iterative. Campbell’s adoption of woodblock, by comparison, regressively attempts to shore up aesthetic value artificially by producing only a single print with a woodblock painted in thick layers of watercolour that constitutes an original work alongside it. The scarcity of Campbell’s work is a decision she makes for two apparent reasons. The first is stated by Campbell herself in response to the question “why I don’t make more than one single print. The answer is simple: I would have to paint the entire block again to make another print… which would be very boring.”

The other reason, stated by most explicitly by Miriam Cosic in The Monthly, is the market. Campbell’s work may not have received major institutional attention, but “she is, quietly, a favourite with art collectors and commands prices to match.” Campbell’s use of woodblocks is indexed to the commercial value of scarcity, rather than aesthetic or cultural imperatives. Commenting on the battle over Australian modernism in the early twentieth-century, Richard Haese distinguishes between those who treated it as a “vital and growing thing,” such as Preston, and those who used it “as a fashionable convention to conceal essentially unoriginal thought and expression.” Similarly, technologies of representation can be appropriated as specific media that make aesthetic demands, or simply vehicles for vapid market-oriented works.

The sharp divergence between Preston and Campbell is not only in their respective approaches to the technical affordances of woodblock printing. It is in their approach to the way influences are incorporated in their work. Sullivan proposes that both Preston and Campbell “adopted and adapted technical and compositional aspects of ukiyo-e.” Penny Bailey, describing Preston’s use of Japanese woodblock printing, distinguishes between Preston’s disdain for “hackneyed artistic appropriations of Europeans traditions” and the way she “adopted Japanese pictorial conventions in her repertoire as part of her own quest to forge a distinctively Australian modern artistic style.” Bailey also notes that Preston’s interests “shifted heavily towards the adaption of Aboriginal patterns and motifs,” albeit inflected “though a synthesis of Eastern and Western idioms.” For both Sullivan and Bailey, “adopt” and “adapt” have a positive, softer valence than forthright “appropriation.”

Margaret Preston, Wheel Flower, c. 1929. Woodcut, black ink hand coloured with gouache on buff laid, Japanese paper, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Bequest of WG Preston, the artist’s widower 1977.

Using “adopt” for both Preston and Campbell obscures the extent to which Preston was a proud, inveterate appropriator. Strident and declarative, Preston makes an argument with technique and aesthetic intention. She takes (steals, purloins) what works, and abandons (even disavows, as Gordon Bennett complains) what does not suit her project. This must be admired for its paradoxical unity, created by forging together materials with opposing forces, composing coherence from what is dissimilar. The fact that Preston is able to pull it off is an aesthetic achievement deserving of Hughes’ praise that no painter “emphasised design with more grace than she.” The least convincing works are ones in which she has retained too much of the original, as in Aboriginal design with Sturt’s pea (1943).

Cressida Campbell, Still life with Ukiyo-e print, 2008. Unique woodblock print. Private collection © Cressida Campbell. Image courtesy of Cressida Campbell and Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane.

Yet this is Campbell’s method, shedding the strenuous demands of aesthetic influence and instead depicting what are meant to be “influences” in what amounts to a jumbled continuation of Japonisme. These unassimilated chunks spoon-feed the viewer a reference and bolster the work’s appearance of sophisticated cosmopolitanism without tearing it out of its amalgamation within bourgeois suburban surroundings. What stands out in works like Interior with Chinese lantern (2018) are other works: the arrangement of prints on the background wall, matched and softened in the plush cushions, the sequence of ceramics, vase and lantern primly framed in the tondo. Campbell, too, incorporates Indigenous people’s works, such as in Black room with yellow chrysanthemums (2022), slyly positioned in the depth of the image, half obscured by a doorway. But this direct appropriation is suspiciously unprovocative. While Preston’s appropriations have earned her responses and rebukes from artists such as Gordon Bennett, Christian Thompson, and Tony Albert (arguably with diminishing returns), Campbell’s work rouses little reaction beyond the philistine cooing, “That would look lovely on the wall at home.” You may slather your walls with Campbell, changing nothing, but you must digest Preston. She tests your constitution.

Scott Robinson is a writer, academic and unionist, published in Overland, Memo Review, Index Journal, Arena, Monthly Review, Artlink, ArtsHub, demos journal and elsewhere. He is currently associate editor at Philosophy, Politics, Critique.