Confined 11

Helen Hughes

Art is commonly described as possessing and enacting a kind of liberatory force. And when it comes under attack, art is often defended with reference to the principle of freedom of expression. This ontological quality of art is tested, if not exemplified, under conditions of incarceration—as a range of high-profile exhibitions in the northern hemisphere have recently shown. One such exhibition, the historical survey The Pencil is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists at New York’s The Drawing Center (2019), explicitly made this point: that for humans in captivity, drawing is a “vehicle through which they proclaim their individuality, express their hope, and imagine their freedom”. The soon-to-open Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA’s PS1 (2020, delayed due to the pandemic) also recognises prison art’s symbolic liberatory force, but not—importantly—at the expense of its abolitionist agenda.

Confined 11 is an exhibition of 300 artworks made by 286 Indigenous artists who are currently inmates of, or recently released from, Victorian prisons. The exhibition is the annual signature event of The Torch—an art gallery and organisation in St Kilda established in 2011, which runs its Indigenous Arts in Prison and Community Program across all Victorian prisons. All the artworks in Confined 11 are for sale, with 100 per cent of the sale price going to the artists—immediately distinguishing art-making from other forms of prison labour in Victoria, which are typically awarded at rates significantly below minimum wage.

The Torch was, in part, established in recognition of the fact that Indigenous people are massively overrepresented in the Australian criminal justice system. Despite constituting around 2.7 per cent of the nation’s population, Indigenous people make up over a quarter of the entire prison population. As The Torch explains: “Today Indigenous men are fifteen times more likely to go to prison than non-Indigenous men and Indigenous women are twenty-one times more likely to go to prison than non-Indigenous women.”

Led by CEO Kent Morris, a Barkindji man, the goals of The Torch’s program are to connect Indigenous inmates to their culture, learn to express that culture through art, and share that culture with their family, friends and the broader public—through gift-giving, exhibitions like Confined, and the sale of their art online and through the St Kilda gallery. The first step of connecting with culture is crucial. Many of the earliest participants in the program, when asked what they would most like to achieve from participation, answered that they wanted to learn about their totems, their Ancestors and creation stories.

Connecting with culture and identity, however, is not always easy or practicable for the artists in the program: that link to heritage has often been actively severed by violent colonial processes of dispossession—for instance, the cruelties meted out to the families of the Stolen Generations—or it is hidden away, as a result of shame or internalised racism. This systemic violence, only notionally “historical”, is also one of the environmental factors that has led to the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in Australian jails in the first place.

The second steps of connecting with family and public are equally vital. As African-American art historian Nicole Fleetwood has pointed out in her recent, landmark study Marking Time: Art in the Era of Mass Incarceration (both an exhibition at PS1 and a book published by MIT, which examines contemporary art produced by inmates of the American prison industrial complex), the use of prison art as a means of connecting with family, friends and the public performs the important work of “resist(ing) the isolation, exploitation, and dehumanization of carceral facilities.” When people are incarcerated, they disappear—overnight, the state renders them invisible to vast swathes of the public. Indeed, Fleetwood’s art-historical project began with a personal photographic installation in her living room: despite the emotional pain it caused, she stuck up pictures of all the members of her family and friends who were then incarcerated to make them visible again—at least to her. The Gunai Kurnai painter Alfred Carter, who first became an artist through The Torch’s Program and now paints two to three pictures a day, notes that he often makes works for family. He paints “so they don’t forget us.”

When prisoners like Carter make artworks for family, friends and public display, and through this act claw back some lost visibility, they do so largely on their own terms. That is to say, art made in prison is, to the extent possible, self-determined, and in this way acts as a powerful counterbalance to the mug shots, cell video footage and racist/classist cartoons that are circulated by an ignorant news media and the state, all of which function to cement negative stereotypes and reinforce cycles of shame. Artworks made in prison also counteract the abstracting language of numbers and statistics, which governments use to describe and dehumanise their incarcerated populations.

Due to the pandemic, this year’s Confined exhibition was installed in a virtual gallery online with the support of German company Kunstmatrix. The 300 artworks are rendered to scale and shown on virtual white walls and plinths. All of the works are hyperlinked to details of the artist, the artwork, artist statements and purchasing details. Visitors to the exhibition are also enabled to leave comments that are passed onto the artists, providing valuable feedback and recognition from the public.

The exhibition is spatially subdivided into three thematic clusters: Animals and Kinship; Belonging and Waterways; and Birds, Bushfires and Country. Each of the walls is covered with a dense salon hang of paintings, and the artists’ words resound in large-format didactic panels. Artist statements accompany most of the artworks, and more general quotes—which explain how art has helped the artists get back on track and learn how to look forward to their futures—are overlaid on the walls and floors. In addition, three-minute-long video portraits of five Torch artists are available to view on the website, giving insight into the role of art in each artist’s transition from prison to community in their own words.

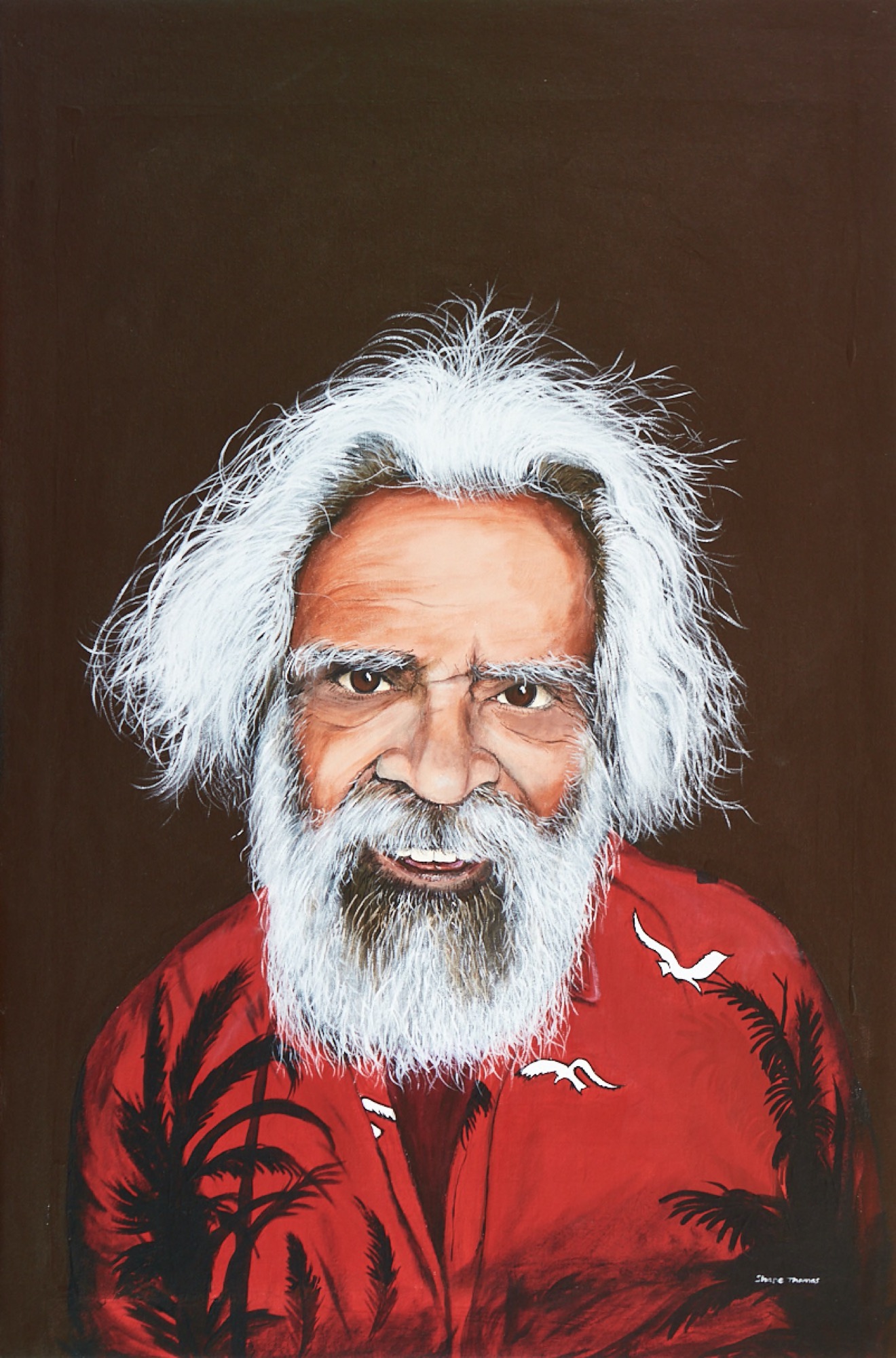

Kinship is referenced with totem animals as well as cultural and political icons. Truganini’s face is the first icon we encounter, with portraits by both the Palawa/Gunaikurnai Peter T and Palawa man, Dale A. Around the corner, we encounter the iconic profile of Eddie Mabo, along with the unmistakable gaze and grin of Uncle Jack Charles—his silver hair and beard captured with the finest of lines in an exquisite portrait by Macca of the Gureng Gureng people (Jack Charles: Where Life Leads Us, 2019). The large-scale Kangaroo Dreaming: Brewarinna by Ralph Rogers (Barrinbinya people) combines x-ray style cross hatching commonly associated with top-end painters and stencil practices many tens of thousands of years old. These images hover over skeins of colourful paint spatters, creating a sense of cosmic space, and are bordered by intricately painted plant tendrils bearing seeds, reminding us of new life.

The galleries dedicated to Belongings and Waterways feature one wall awash with paintings united by a common colour theme: cerulean blue hues, reminiscent of pristine waters. Here, dolphins frolic, a school of turtles floats by, seahorses proudly puff out their chests, platypus swim in the shallow of a stream, yabbies bear their claws, octopi their tentacles, stingrays glide, eels slide and crabs scuttle. The mesmerising Oppression of our Waterways by Angela Hood (Gunditjmara/Gunaikurnai people), by contrast, is a non-figurative treatment of this theme; its maze-like paths created in the negative space of interlocking shapes address “the Murray River losing its water to the cotton farmers through irrigation and the effect that has on our spiritual ways of connecting to Mother Nature”.

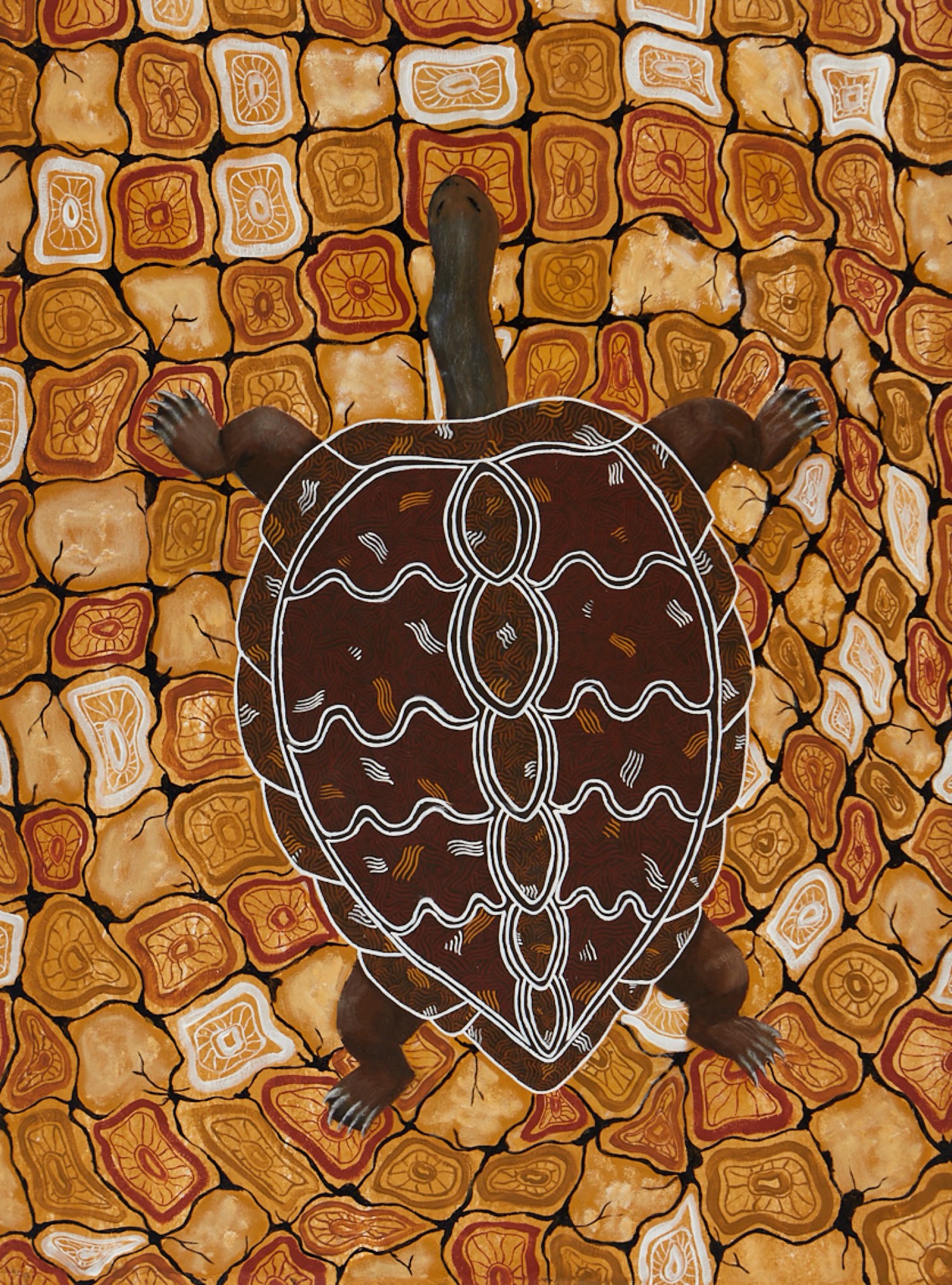

Another wall is hung with paintings grouped around earthy orange-brown tones. Here, Christopher Austin (Gunditjmara Keerraaywoorrong people) presents Our Changing Climate (2020)—an aerial view of a turtle walking up a dry river bed. The river bed is so parched that it’s riven with cracks that emulate the scutes of the turtle’s shell, creating a fractal-like continuity between animal and land. The artist explains: “This is the sad result of human greed and pollution changing our climate”, highlighting the profound damage wrought by centuries of non-Indigenous governments and corporations neglecting obligations to care for Country. Just last week, on the Western flank of the Australian mainland, Rio Tinto blew up a 46,000-year-old Aboriginal heritage site at Juukan Gorge in the Hammersley Ranges in order to expand its iron ore mine, then offered a limp apology to its original custodians, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura People. In March, while the Victorian population was overwhelmed with the coronavirus crisis, the Andrews government passed a law allowing onshore gas exploration from July 2021.

In addition to paintings, we find in the Belongings and Waterways gallery a range of other media too: kangaroo skins embellished with poker designs by Barkindji man Trevor and Gundijtmara man Christopher Pillgram; painted or poker-worked boomerangs, shields and yidaki; a suite of plinths displaying finely woven baskets, including Torres Strait Islander Sonia’s raffia basket titled Near the End of My Journey (2019), created as the end of her sentence approaches; and a series of four finely patterned silk scarves made by Gundijtmara woman Lodi Lovett, which have been created using natural dyes extracted from locally sourced eucalyptus leaves amongst other plant materials, such as onion skins.

It is, however, the Birds, Bushfires and Country gallery that holds some of the most resonant contemporary artworks. Gary Reid’s (Pitjantjatjara/Yankuntjatjara) Waru Pulka/Bush Fire (2020) is a swirling haze of bright yellow, orange and ochre-coloured lines and dots that describe snakes, leaves, lizards and footprints—shot through with the tiniest glimmers of sky-blue pigment. Veronica Mungaloon Hudson’s (Pitjantjatjara) Burning of the Land #30 (2020) references Indigenous land management practices of burning to make way for new growth. As Hudson explains in her statement, she used grasses and branches to create the rising flickers of colour, leaving some of the seed heads and grasses embedded in the pigment itself—a symbolic and literal promise of new life after the flames.

Perhaps the most striking image is Littledoo’s (Wangkumara people) Bushfire (2020). A long, frieze-like vista, Bushfire appropriately takes on the proportions of a history painting as it depicts burning Country throughout East Gippsland in the January 2020 bushfires. In Littledoo’s painting, everything that can burn is alight: the grass is rimmed with yellow flame halos, kangaroos hop helplessly into the inferno, quiet koalas perch resignedly in trees on fire, a tin shed in the background is ablaze—even the rickety legs of an old water tank are going up in smoke. In the upper left corner of the canvas, fire seems to be raining down from a heavy cloud. And the sky, if we can call it that, is that thick grey poisonous smoke—that suffocating blanket which descended on metropolitan cities, just in case urban dwellers would have preferred to ignore what was going on in the bush. This forceful work by Littledoo belongs next to the pairing of William Strutt’s Black Thursday, February 6th, 1851 (1864) and Juan Davila’s Churchill National Park (2009), painted en plein air after the February 2009 bushfires, which hang as a pair in the Cowen Gallery of the State Library of Victoria, to add to this rolling chronology of devastating and ever worsening fires.

While each artwork in Confined 11 is distinctively the product of an individual maker, certain broad commonalities emerge looking across the 300 artworks as a whole—and especially across the paintings, which easily constitute the dominant medium in the show. The paintings, for instance, are principally executed in acrylic (fast-drying, easy to clean, compatible with non-toxic mediums, more vivid in colour and cheaper than oils) and many are unstretched (storage space is at a premium, though The Torch stretches all paintings for free upon purchase). Curiously, in terms of content, there are no scenes of cell interiors, no realistic portraits of other inmates or family (though family is symbolically represented frequently in other ways), nor any erotica—the genres so common amongst artworks made in prisons elsewhere in the world. In terms of technique, clear, sharp brushwork and repetitive patterning is widespread, evidencing acute levels of concentration if not meditation. In the perfectly rendered accumulation of dots and lines, seen for instance in Mick D’s My Totem Long Neck, the lost time of doing time is transformed into the production of something highly ordered and beautiful, and in which the artist effects a level of control and agency otherwise not afforded them within the institution.

Art programs in prisons, as in other institutions like psychiatric wards, hospitals, schools and rehabilitation centres, are often aimed at achieving therapeutic outcomes. And it would be ignorant to deny the immense therapeutic impact of these works, especially as the artists themselves—like Ashley Thomas in his video portrait—specifically cite healing as a strong motivating factor behind their practice. That said, it is important to acknowledge simultaneously the powerful personal transformations effected through the art and the limitations of an art therapeutic interpretive framework—especially amidst the larger issue of racial injustice. As Nicole Fleetwood has cautioned, the problem with understanding prison art through “a rehabilitative framework is that in its primary focus on changing the individual, it does not offer an analysis or critique of (…) the carceral state” itself. This double-bind is one of the methodological hurdles associated with the study of prison art. A reading too closely focused on the individual inmate artist risks reinforcing the way carceral institutions can responsibilise the prisoner with the task of their own rehabilitation, whilst ignoring environmental factors like racial inequality. However, a method that veers too far in the opposite direction—a properly structural analysis—risks ignoring the vital life-force of the individual and their artwork, made in spite of the dehumanising conditions of prison.

While the carceral states of America (Fleetwood’s area of study) and Australia are decidedly different—in the first instance, the percentage of incarcerated to free subjects in the US is a staggering 655 per 100,000 of the national population, whereas in Australia it is 169 per 100,000 (though this figure does not include Australia’s off- and onshore detention centres for refugees and asylum seekers, which are technically distinct from prisons, but are, for their inmates, effectively the same)—they are by no means unrelated, especially in their treatment of black and brown bodies, and the poor and working classes. As the Australian Bicentennial approached in the 1980s, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were dying in custody in such great numbers that, by 1987, the overwhelming evidence of a lethal and racist criminal justice system necessitated a Royal Commission. Yet in the three decades since, little has changed. Few of the Royal Commission’s recommendations have been adopted, with the ACT and Northern Territory implementing the most, and Victoria the least. More than 400 Indigenous Australians have died in custody since the Commission delivered its findings in 1991. No convictions for any of the correctional or police officers responsible for the deaths have been made.

I write this review in the context of the events unfolding across America over the last week: the murder of African-American man George Floyd by white police officers in Minneapolis, and the days and nights of relentless protest that have ensued in cities across the country. Protesters’ placards and chants of “I CAN’T BREATHE”—the phrase repeated by Floyd in the last minutes of his life as an officer kneeled on his neck—sparked new terror and solidarity in the family of Dunghutti man David Dungay, who was killed in 2015 when guards at Long Bay jail hospital stormed his cell because he refused to stop eating a packet of biscuits, then held him face down while a Justice Health nurse injected him with a sedative. As numerous commentators have noted, Dungay, like Floyd, tried to make his voice heard. “I can’t breathe”, he too repeated, twelve times, before he fell unconscious then died. Indeed, this afternoon (Saturday June 6, 2020), Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance will lead a protest in Melbourne under the banner of “Stop Black Deaths in Custody—Justice for George Floyd #BLM.” Confined 11, then, is not just a “strong visual metaphor for the over-representation of Indigenous Australians in the criminal justice system”, as the media release suggests, but a damning indictment of the bond between patterns of incarceration and criminalisation and systemic inequality and political disenfranchisement—a grim handshake that resonates in all corners of the world and throughout all periods of history.

Confined 11 does not critique the carceral complex, per se, or at least not directly. One of The Torch’s taglines is: “By embracing participants as artists rather than ex-offenders The Torch provides an avenue for change.” In downplaying the “prisoner” to make way for the “artist”, the framing of the exhibition in some ways trades off a structural critique of the criminal justice system to, very practically and understandably, foreground themes of positivity, courage, hope and future, as well as make immediate pathways for Torch artists into better lives. The exhibition’s lost opportunity, however, is the possibility of collectively articulating justice from an incarcerated perspective—an understanding of which, to again quote Fleetwood, is deeply troubled by “aesthetic practices that emerge from, not despite, systems of punishment”. An artwork that has recently come up for sale on The Torch website by Flick Chafer-Smith (Ngarrindjeri people) articulates this complexity with commanding economy. The new work is very different in colour palate and subject matter to the artist’s painting New Life, included in Confined 11, which depicts a silhouetted koala in a tree against a brightly coloured, Op Art–like backdrop of zigzags. Her new painting Black Bodies Behind Bars (2020) comprises a black monochrome backdrop against which four pairs of black, disembodied hands grip vertical grey bars, evocative of a prison lock up. The bars, however, are embellished with concentric diamond patterns, and may thus also be read as spears—instruments of war, hunting, justice and culture. The work documents Indigenous dispossession of, then imprisonment on, Indigenous land. In the artist’s words, it depicts ”the over-representation of our people in jails”. And in so doing, this painting carries within it (not unlike the seed heads in Veronica Mungaloon Hudson’s bushfire painting) both a glaring assessment of the system and the tools with which to fight it.

Confined 11 can be viewed here.

Helen Hughes is a Lecturer in Art History, Theory and Curatorial Practice in the Faculty of Art, Design & Architecture at Monash University.