Braving Time: Contemporary Art in Queer Australia

Jade Muratore

Braving Time: Contemporary Art in Queer Australia is, as curator Richard Perram asserts, a show “about contemporary art in queer Australia” and not “an exhibition of queer art in contemporary Australia.” As I attempt to unpick the subtle sematic differences between these two frameworks, I wonder if they aren’t really one in the same. Is the curatorial objective of foregrounding queer subjectivity and worlds in Australia and Australian art not also an exercise in queering contemporary art and Australia? I’ve barely made it past the introductory wall text and my mind is already whirring with unanswered questions.

The works in Braving Time centre on one unifying feature: all artists “identify as part of the Australian LGBTQIA+ community.” While curatorial frameworks focussed on identity are neither new nor departing anytime soon—think of the NGV’s Queer (2022), the NGA’s Know My Name (2020–22), and ACCA’s Unfinished Business (2017–2018)—such approaches raise a number of questions around criticality, nuance, and cultural relevance. Shows that thematise or privilege identity may seem like the most egalitarian answer to the enduring lack of diverse representation in our public art institutions—see Rex Butler’s review of Who Are You: Australian Portraiture, 2022. But their resulting exhibitions often lack the conceptual scaffolding required to adequately platform the artworks on show. Identities are broad, slippery, and idiosyncratic. These idiosyncrasies demand conceptual structures with enough specificity to guide the audience’s critical engagement with the artworks on display (examples of recent shows that have offered such a rigorous and generative structure are Fulgora (2023) and Screwball (2022), both curated by EO Gill, and Friendship as a Way of Life (2020), curated by José Da Silva and Kelly Doley). Without strong conceptual structures, the discursive potential that can exist between distinct works of art and their relationship to the stakes of queer living and histories are lost.

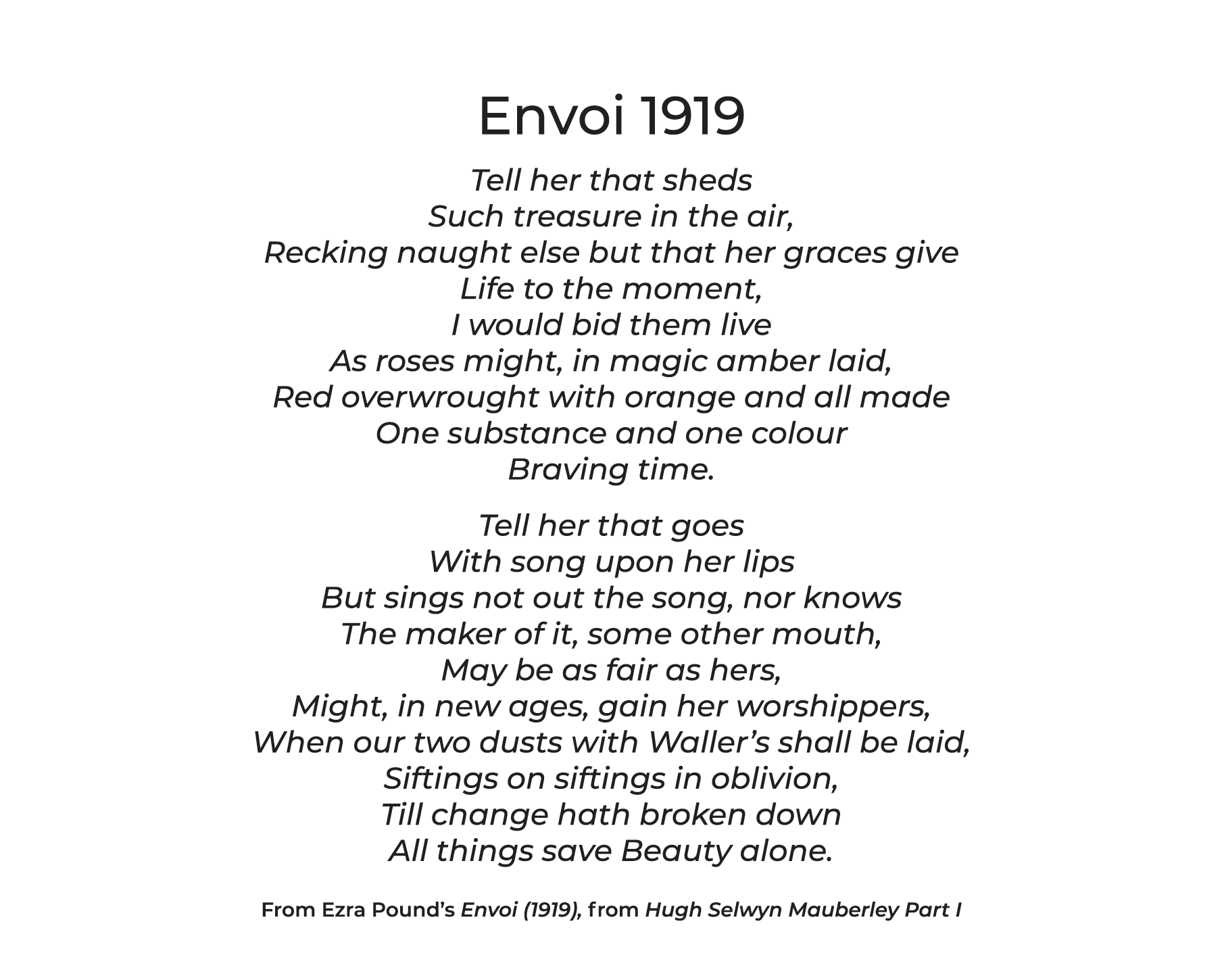

In Braving Time, Perran eschews specificity for a particularly wide berth and presents us with a long list of exhibition themes: “Our Queer Ancestors, Queer Worthies, Death and History, Feminist Expression, Family and Community, Maleness and Power, Humour, Gender and Sexuality.” That’s a lot of ground to cover. And while it’s broadly possible to see how each thematic might finds its kin among the works on display, I find the scope disorientating. Not disorientating in the way that Sara Ahmed means when she advocates for a queer politics of disorientation that undoes the seemingly compulsory orientation toward heteronormative horizons. Rather, the show was disorientating because it’s dizzying array of themes led me nowhere. Searching for something to help me critically engage with the works, I latch onto the exhibition’s title, taken from the Ezra Pound poem Envoi (1919), in which Pound muses on beauty’s potential to eternally “brave time” through art.

But what does it mean to “brave time”? Furthermore, what does it mean for beauty to endure through time, and what does this enduring beauty have to do with queer subjectivity? Perram’s curatorial statement does little to shed light on such questions, so again, I turn elsewhere: this time to Saidiya Hartman. In Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), Hartman states: “Beauty is not a luxury; rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical art of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.” This is beauty as it resides within the quotidian, as well as on the margins. It is beauty as potentiality, as survival, and as a force that “propels the experiments in living otherwise.” It is art’s ability to render the beauty in everyday life as well as its ability to infinitely reproduce that beauty across time, like a song passed down through generations.

The tendency toward adornment, baroque, and excess is typical of queer aesthetics. We find it in the ornate tableaus in the films of Derek Jarman, and in the opulence of Black and Latinx Ballroom culture (“O-P-U-L-E-N-C-E. Opulence! You own everything. Everything is yours,” proclaims Junior LaBeija in Paris is Burning of 1991). It is present in Cassil’s durational performance practice that excessively pushes to the limits of the body, and Lil Nas X in Marie Antoinette-style coiffure and drag for the MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name) music video of 2021. The signs and gestures proliferate where queer politics and visual culture intersect, not only as a salve against the harsh realities of minoritarian existence but also as a method for mapping future social relations. Susan Sontag said it best: “rules of taste enforce structures of power.” Several of the artists in Braving Time engage with beauty to complicate and/or critique hegemonic power structures. It is these artworks that manage to cut through the conceptual ambiguity of the exhibition as a whole, beginning with the first group of works gathered under the leitmotif of the flower.

In the opening room, Troye Sivan’s sugary synth-pop track “Bloom” (2018) resonates over this discrete cluster of works, which includes Christian Thompson’s photographic self-portrait Ellipse (2014), Fergus Greer’s portrait of Leigh Bowery (Leigh Bowery, Session IV, Look 23, 1991), and Deborah Kelly’s cock-shaped floral collage aptly titled Floral C(l)ock (2004/2023). In Kelly’s work, a rich mass of luxuriant blooms is printed onto black velvet and embellished with diamantes, emphasising the fecundity that such flora represent. Like the rose in Pound’s poem that braves time in its amber tomb, the flowers are frozen in their ripeness. This flourishing is set against the grim conceptual undertone of the work, as a commemoration of ACT UP’s 1991 D-Day action protesting governmental negligence in addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis. The tension of beauty and grief, survival and ruination in Kelly’s work speaks directly to Hartman’s conception of beauty as a “radical art of subsistence.” In the face of systemic cruelty enacted against queer people, we push back with grace, luxuriance, and good humour.

Unfortunately, the conceptual cohesion of the first room isn’t repeated throughout the rest of the exhibition. Vivienne Binns’s infamous vagina dentata Repro Vag Dens 3 (1976), and sombre oil portrait Seated Woman (1958–62) sandwich together two of her darkly abject pen and ink series on the psychosexual development of adolescents. These are positioned adjacent to William Yang’s heart-rending photographic series Allan (from the monologue Sadness, 1988–1990 of 1994)—nineteen profoundly intimate portraits of Yang’s friend, and former lover, Allan overlayed with Yang’s hand-written commentary sharing personal insights and memories on a life lived and lost to complications from HIV/AIDS. NELL’s parliament of smiling ghosts rendered in earthenware, concrete, glass and even traffic cones sit patiently in the centre of the ground floor gallery but compete with a cacophony of form and colour in Christine Dean’s vibrant abstract paintings overlaid with busy textile/text.

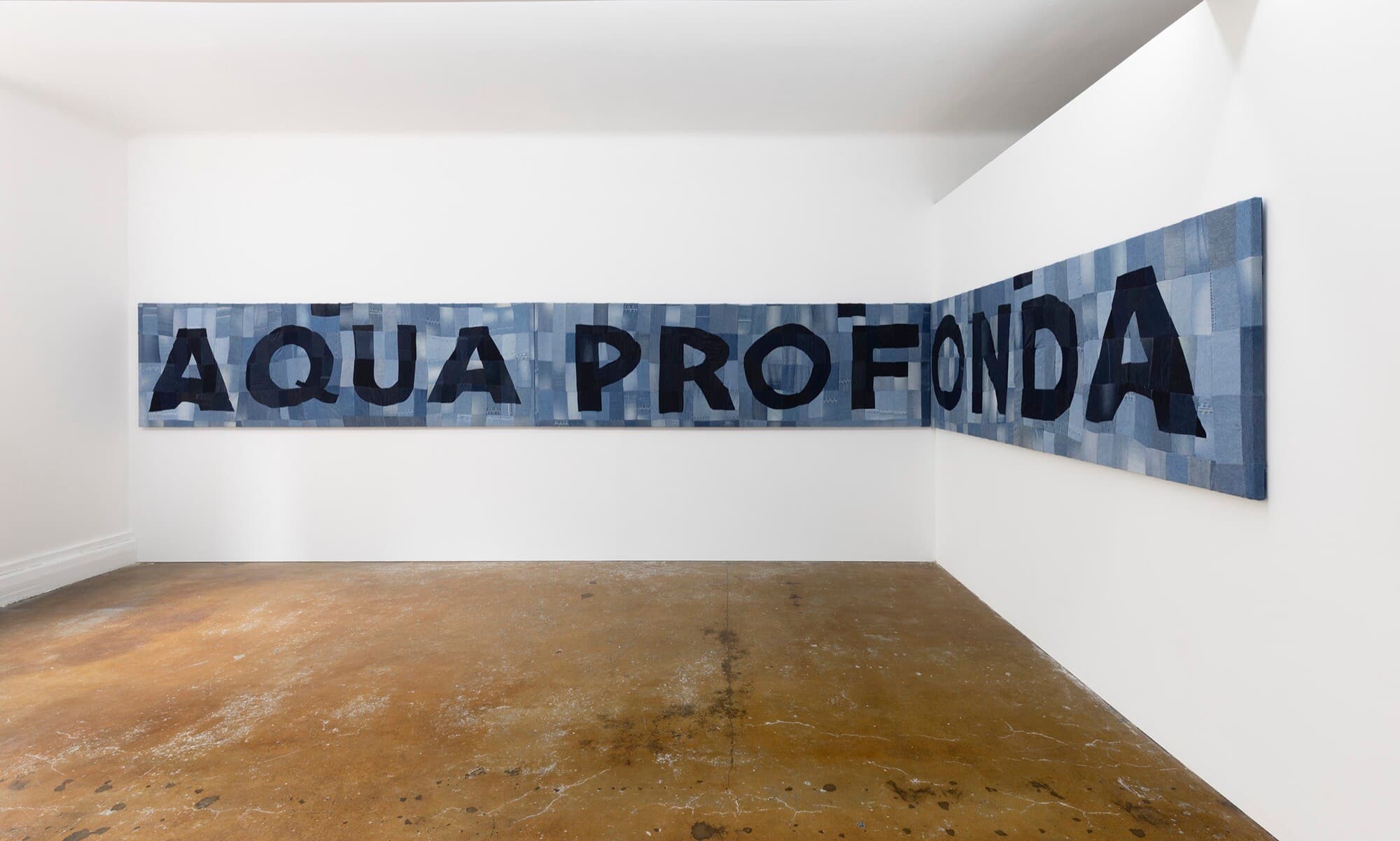

Upstairs, Tim Silver’s can I, just wait here with you (2022) presents two, life-sized naked men standing in an intimate embrace. Cast in a copper infused gypsum, the milky green patina gives them a ghostly complexion. These spectral figures are surrounded by Salote Tawale’s formidable sculptural self-portraiture, Todd Fuller’s reimagining of gay eroticism in early colonial Australia, Kate Just’s snappy knitted protest banners, and Emily Parsons-Lord’s elegiac renderings of the colour signatures of stars.

Curatorial approaches centred on identity risk collapsing what are distinct subjectivities, histories, and worlds into “all inclusive” assemblages. When you collapse all the unique subjectivities of LGBTQIA+ into one signifying whole, the chance to work at critically unravelling the myriad ways in which queers endure, hold, or brave time is wasted. We have long made worlds out of, and with, the queer communities we cultivate and cherish (and World Pride is apparently one of those worlds). These worlds are multiple, compete with, aid, supplement and/or undo each other, and cannot be reduced to a flat and all inclusive “queer contemporary” aesthetic. Specificity is needed (á la Screwball et al.): braving time is not a universal experience. In Perran’s show “LGBTQIA+ identity,” as a conceptual framework, paints “us” with the same homogenising and over-simplifying broad strokes as those pesky master narratives. Everyone in the rainbow acronym has long been trying to dismantle the burden and false seduction of master narratives as a matter of survival, so why subsume us into yet another one (even if it is rainbow coloured)?

If the world of contemporary art is going to continue its courtship of queer artists, its curatorial frameworks need more critical rigour than simply a desire for greater inclusivity. Inclusion alone is little more than the act of opening a door. We need greater clarity around what happens on the other side of that door, what specific questions are being addressed, and what “conversations about queer experience” (to quote Perran’s curatorial statement) do we want addressed?

Jade Muratore is an artist and researcher based in Sydney/ Eora.