Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium; wHole

Kate Butler

Barbara Hepworth: In Equilibrium seems to repel criticism. Putting aside the fanfare of it being the artist’s first major survey exhibition in Australia, the sculptures are above all affirmative rather than critical: harmonious, organic forms of stone, wood, plaster, and bronze. While the concurrent contemporary exhibition wHole, at Heide Modern, offers a few glimpses of the influence of Hepworth’s formal vocabulary, the selection of works reflects a contemporary view of art-as-critique that stands in contrast to Hepworth’s modernism.

So, are we to appreciate Hepworth’s sculptures as relics of a moment in Western art history that’s long since run its course? Having made my way through both exhibitions I was left wondering what place, if any, the artist’s craft-based formalism and affirmative ethos might have in art practice today. While her figure-inspired works reflect an idealism typical of many mid-century sculptors, her more voluminous, “closed” and “pierced” forms bring to light what made her work radical to begin with. The best of them compel us not just to look at visual compositions of shape but into tensile interplays of surface and depth, mass and emptiness, here and now.

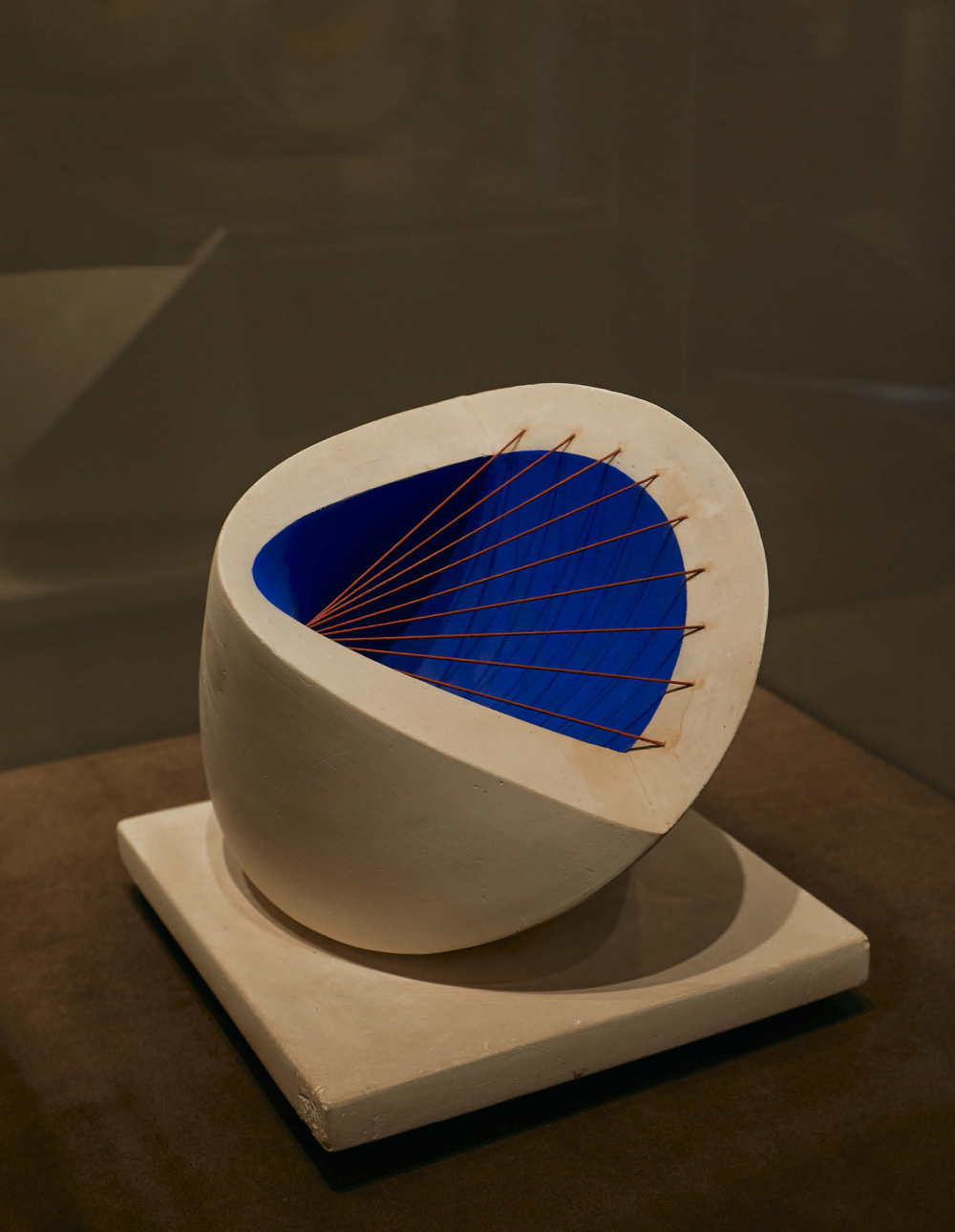

One of three form-types that occupied Hepworth through her career, the “closed form,” uniquely signified not a feelingtoward a natural or human motif outside but an inhabiting of a phenomenon from within, expressed in the embrace of material around a central hollow. Among the many iterations of this motif on view in the exhibition, I found her stringed forms—a cluster of them are situated to the left of the front gallery room—revelatory in their expressions of being in the world. Dating from the 1940s, 50s and 60s, the works see the grammar of landscape drawing integrated into voluminous, bodily, wholes. Orpheus (Maquette 2) Version II (1956–59), for instance, is composed of a sheath of copper evocative of a ground plane that, twisted and torn, stands upon a wooden plinth like a dancer poised on one leg. The work transcends any one signification: it is sort of a figure, but also invites viewers to look into a space in the way one might look into a landscape. The planes of string, splayed out, taut, receding toward a point, resemble the orthogonal lines of a perspective drawing. And yet they do not so much direct the vision as engulf the gaze, twisting and overlapping with each other or else receding to a point at which the surface continues to lead the eye along. This ambient, tactile space Hepworth takes a step further in Sculpture with Colour (Deep Blue and Red) (1940) by painting the interior an ultramarine blue. Red strings, flaring out along a top edge of the plaster form, recede into the well of colour, their warmth deepening our sense of the interior’s depths.

Hepworth understood a central aim of sculpture to be the evocation of “primitive feeling,” encompassing tactile sensations and emotions fundamental to human embodiment. These are feelings that many of her closed forms approach, whether by way of the tension and recessions in the stringed works, as in the faceted coloured surface of the carved stone Eidos (1947) or the texture and dynamic overlays of Maquette (Variation on a Theme) (1958) and Oval Form (Trezion) (1964). The sense of touch was broadly understood to include all manner of physical sensations Hepworth understood to be part and parcel of an authentic relationship to reality, which was all the more essential in the face of the disaster of the Second World War. When Hepworth was in her fifties, personal tragedy gave new urgency to this purpose. The largest carved work in the exhibition, Corinthos (1954–5), was created following a trip by the artist to Greece a year after her son Paul’s death in a plane crash. In the following year, she created more literal commemorations, among them a monolithic abstract figure as an ode to Paul and his navigator, followed by a more representational stone carving depicting a Madonna and Child. In Corinthos, it is the embrace of the sea that is evoked through an internal centrifugal passage, carved out from a single piece of Guarea hardwood. White paint coats the interior, reflecting light like the surface of the sea, as if arching around a central void of a wave.

One could be absorbed by the subtleties of this interior, the heart of the work’s harmony, before stepping to the side and looking at its polished exterior with something between puzzlement and longing. The outer surface of Corinthos sees the movements of the wood’s grain and rings sealed as if a fly in amber. Aware that disclosing the character of her specific material was very much not Hepworth’s modus operandi, I couldn’t help but wish that she had embraced something of the wood’s rugged reality—some expression of its texture, its history, freed from the artist’s hand. One is confronted with the fact that Hepworth has opted for an ideal organic harmony to the exclusion of the perhaps more complicated unity of the thing she was carving from.

Such idealism, coupled with material aloofness, characterises many of Hepworth’s upright, figure-inspired sculptures, inspired in part by the ancient stone monuments that decorate the Cornish hills. Take Two Figures (Menhirs) (1964), which consists of a pair of polished stone monoliths. Composed of simple interplays of abstract shape—one plinth, two monoliths, cut with two different shapes—the piece is archetypal of human figures, patiently co-existent, their forms stoic and self-contained. This composition is not entirely to blame for the generic nature of the piece. Rather, it’s the absence of any evocation of time’s passing, epitomized in its polished stone surface. There is scant disclosure of the material’s particularities, no reference to a specific, temporal experience, and little dimensionality to invite an experience of the work in time. It is, after all, evidence of decay that makes the continued existence of ancient stone works so remarkable; it lends weight to their “timeless” expressions of human ingenuity.

Two Figures, and similar works on view like her three maquettes for The Unknown Political Prisoner(1952), entitled Truth, *Prisoner*, and Knowledge (abstract concepts rendered in correspondingly abstracted forms), brought to mind John Berger’s critique of Hepworth’s sculptures. Berger, a Marxist, accused the artist of failing to “face up to the real consequences of the times in which we live” by abstracting reality, “inventing a substitute ‘ideal’ world” instead of investigating “actual structure.” It wasn’t necessarily material structure to which Berger was referring but some particular aspect of the concrete existence by which to approach the universal. Within a faithless society, vague symbolism is of little consolation; what was needed, Berger believed, was “the most faithful insight into what it means to be a particular person in a particular situation.”

Heide Modern’s wHole, curated by Melissa Keys, could have been an answer to Berger’s charge. Whereas Hepworth’s sculptures aspire to universally intelligible expressions of essentially human experiences, wHole encompasses a multiplicity of different viewpoints by seventeen living and deceased artists, their positions explained by wall labels, paragraphs long. Besides providing necessary context, the accompanying wall labels often point to formal constructions already communicated in the works themselves, as with Rushdi Anwar’s installation Reframe ‘Home’ with Patterns of Displacement (2019), a patchwork of Middle Eastern carpet swatches incongruously placed and riddled with openings, situated beneath video footage that situates this composition in a place in time. As many of these works are meditations on absence, the wall labels also function to name what the artist has purposefully omitted. James Tylor’s (Vanished Scenes) and (Removed Scenes) from the 2018 Untouched Landscape series include holes spliced from black and white photographs of Australian landscapes, attesting, as the label clarifies, to the absences of First Nations people within them.

These works, like a large number of the works in wHole, deal with the hole as motif and metaphor. But, despite appearances, many share little in common with Hepworth’s sculptures, whose voids and hollows are not true absences but balancing presences in spatial expressions of genuine, idealised wholeness. Yet (puns aside) the hole, not the whole, remains the show’s primary focus, a motif that the wall labels themselves reinforce. Sometimes, as I’ve said, they name what the artist has purposefully omitted, and at other times the text pokes holes in works that would appear to be—precariously, poetically—already complete. I think of the label for Mira Gojak’s Attachments of Colour (2022), an abstract composition of metal rods, one tall and positioned on the bench, its top arching over at ninety degrees, five cymbals affixed through with lines of coloured thread that run into their holes and angle out along their faces. On the floor below, another metal rod is bent down, one arm holding a single cymbal, attached as if to secure it from rolling off. Much in this work resonates with what Hepworth regarded to be athe purpose of sculpture: to speak directly to physical being by way of certain materials and colours composed in space. But the accompanying three-paragraph label suggests the inadequacy of this experience, speaking of some things that are readily apparent and others that are nigh-impossible to glean (for example, that the cymbals act as “tremulous harbingers of the coming climate crisis”). The sculpture is where the artist and the viewer meet: while context and concepts give us our bearings, elaborate explanations risk opening voids in one’s encounter with the thing itself.

It was curious to see such a heady Hepworth-inspired show when, today, some version of her biomorphic language of voids and masses lives on in the art of craft sculptors working in wood, clay, and limestone (including Noriko Nakamura, one of the artists featured in wHole). Likewise born of a direct engagement with material, work in this vein might take the form of carvings with sinuous curves, totemic abstract objects, or ceramic sculptures with voluminous central openings, some plainly commercial, some refreshing in their wholeness and mysterious in their materiality. The sensuality of organic, biomorphic, and/or craft-based sculptures doesn’t preclude them from being critical or challenging, but such works do lend themselves to the sort of affirmative ethos that defined Hepworth’s practice. Artists need not imitate modernist motifs to make work that affirms and awakens experiences of embodiment, as Hepworth did — we need only attend to the particularities of our materials, to lean into our most idiosyncratic perceptions of form and space.

Departing wHole for the rolling hills outside, it was the invitation of Hepworth’s sculptures to enter and explore that my thoughts returned to. “I wanted to make forms to stand on hillsides through which to look at the sea, forms to lie down in, or forms to climb through,” the artist once said. The works in the Heide show may have been indoors on pedestals yet somehow, at best, this is what they allow you to do.

Kate Butler is a ceramic sculptor/teacher, arts writer and arts worker based on Wurundjeri land in Melbourne.