Assembled: The Art of Robert Klippel

Victoria Perin

Robert Klippel isn’t my genius. Despite knowing that his insights don’t move me, I enjoy being in his world, in which the logic of the hand is trusted tenfold more than the logic of the head.

Klippel was not a thinking artist. He consistently (including in the video accompanying Assembled: The Art of Robert Klippel) spoke about how much he did not understand and did not get along with the majority of people who spoke about art. He is painfully explicit when emphasising his youthful interest in model-ship building, a hobby that he had wholeheartedly imagined would be his life-long passion. It was surprising to Klippel when, at the age of 20 years, art literally replaced model-making. Three years later in 1947, after attending art school in Sydney and London, Klippel was in the grips of a drawing mania, but could make no sculptures. He wrote in his notebook: “Feel very stimulated to build model ship / Royal yacht. / Base carving or Ship Form Which I know well (his emphasis)”. In a time of creative struggle, the still-young artist just wanted something he could mindlessly copy. A nostalgic impulse from a time of great uncertainty.

Klippel had left Sydney in March 1947, and he lived in London for an intense year and a half, before moving to Paris from December 1948 to July 1950. In Paris, Klippel wrote a note in one of the little sketchbooks that he kept in his pocket, with original spelling intact, it reads: “Types of sculpture / Religious / Decorative / Outdoor / Monument / Doors / gates / Romantic / Classical / Non Objective / Surrealist / abstract / Constructavisim / academic / primative”. I find this list unspeakably charming (“doors” distinguished from “gates”!). The implications of the young artist gingerly sorting through his medium, trying to locate his own practice, are so tenderly felt.

His principal theory, which he came up with before these years in London and Paris, was called the “language of forms”, and TarraWarra’s guest curator Kirsty Grant makes ample use of this phrase in the wall-text and exhibition catalogue. All writers on Klippel must reckon with this theory, and some have waxed lyrical about it. Perhaps the waxing isn’t necessary; when you see him developing this idea in his 1947—50 sketchbooks, what becomes clear is how practically literal this theory was. Klippel meant the “language of forms” so literally that he went so far as to illustrate a few chunky alphabets out of thick, stony-looking typography.

Gleeson writes how, for Klippel, practising art was like increasing your vocabulary in a language in which you are not native. Forms were like letters in an alphabet that you combine to create words, and string together to speak in sentences—at first haltingly, then eloquently. What Klippel’s idea lacks in poetry (these are not Ezra Pound’s ideograms), he made up with genuinely staggering quantity. If the “language of forms” was anything more than an idea of base shapes with which you could assemble, it was perhaps also a work-ethic. To know forms, one had to practise them over and over again until composing became akin to a spontaneous act. Quick, focused and repetitious: studying forms in sketchbooks, Klippel attempted what was essentially an artistic training regime. Take this self-instruction from the late 40s: “Warm Shapes / Cold … Use every possible form / Round, pointed, square, … Convex, Concave / Great variety Necessary —- / Dont worry about repeatition(sic) / in carving”.

From London onwards, after abandoning stuffy life-study classes, Klippel began drawing sculpture, drawing what he saw in the British Museum, in the Natural History Museum and at contemporary art dealers. However, rather than sketching complete sculptures, Klippel began routinely disassembling each piece. He’d work up a page of shapes favoured by one or another artist. One page is inscribed “Gaudier-Brzeska forms” after Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, one of his favourite artists. He drew a similar page for Pablo Picasso, which is on display in this exhibition. But far from an idealistic modernist, by and large Klippel had difficultly relating to the contemporary schools of sculpture that he saw in Europe—particularly surrealism, a movement he is often lumped with, but that he associated with figuration.

Klippel came across surrealism and tachismeat roughly the same time, mediated by his great friend, Australia’s gentleman surrealist James Gleeson, and French-Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle. Again, by his own admission, Klippel didn’t really get surrealism; however, he did grab hold of the idea of automatic or unconscious mark-making. By the same turn he adored tachisme’s intuitive, free-form expression. In addition to these aesthetic movements, Klippel continued to pursue the “deeper reality” of Zen philosophy. Moreover, in the literature on Klippel, Buddhist meditation and the concept of “absent thought” is presented as roughly equivalent to surrealist and tachist thought.

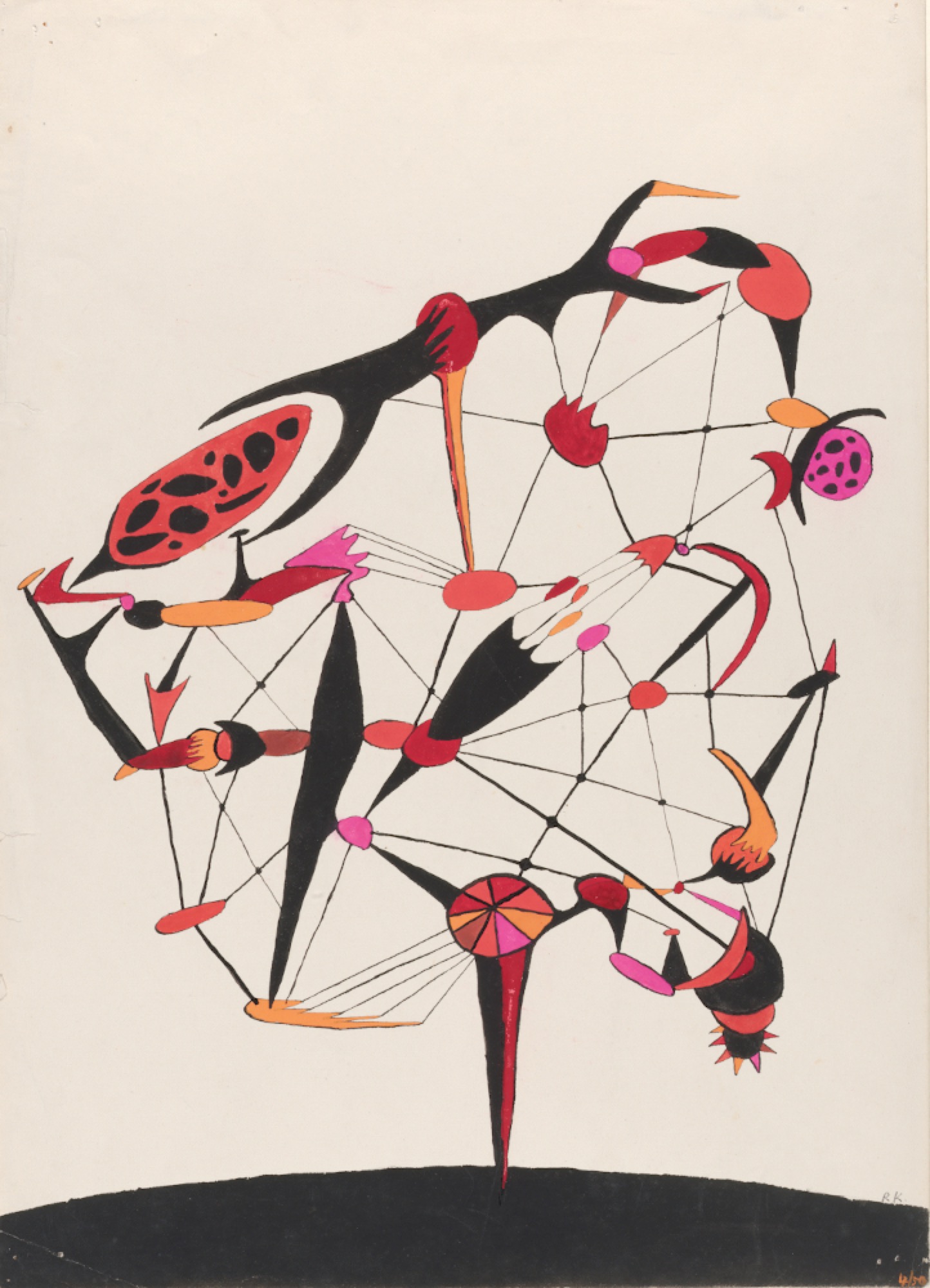

Klippel did not need surrealism, or abstract expressionism, or Zen philosophy to make his art—although, his sketchbooks record how he did find it supremely gratifying that these big theories could support his practise. In fact, Klippel saw justification for his intuitive practice in all sorts of disciplines. Take another quote from his sketchbook that reads: “After seeing models of atoms—crystals, etc, (…) (I) feel more convinced than ever that my abstract idea of volume forms (has) a complete relativity with Nature generally”. It was about this time that he began using wooden dowels to suspend and connect different elements. Atomic particle models confirmed to Klippel that at the heart of the universe there were unseen internal forms, which combine into rational wholes. TarraWarra only have one of these sculptures, Fever Chart (1948), but they have many more wonderful drawings illustrating this home-spun mishmash of science-y, semi-philosophical, and fashionable aesthetic theories.

Materials, rather than theories, were one of young Klippel’s key anxieties, precisely because he seemed to have so few solutions. He was, by training, a carver of stone and wood. How was he supposed to construct these wild sculptures he was drawing? One of his most famous drawings (not in this exhibition) aspired to make parts of his sculpture hover with the use of super-strong electro-magnets. Various notes from this period suggest a sort of agitated search for acceptable parts with which to configure his “language”:

“Shapes suspended—with string, wire or dowels”; “wood coloured + > wire”; “simple shape with various small shapes drilled in—Various > woods”; “shapes resting on springs, coloured springs”; “Coloured > discs”; “Concave / flat coloured steel”; “plaster and wire”; “coarse > rough wire…”.

Klippel’s experiments on paper eventually evolved his sculpture beyond the solid and the round. Before he even conceived practicing assemblage, Klippel drew himself out of carving. He seems to have found this enormously exciting, but also frustrating.

Throughout his life, in times when Klippel did many drawings, he completed few sculptures and vice-versa. As if the two mediums could not share his attention; his own very pressing dialectic. In July 1949, energised, Klippel wrote: “Have done a great many drawings. Very diverse in range and scope”, then, deflated, he adds, “—but the problem of doing sculpture is great. How to get started again?” Collage and assemblage became his answer. But it took a decade before he traded generic metal bits for the recycled metal junk material that became famous for. From this point on creating was easier for Klippel, as he no longer had to invent the basic bits of his sculptures. His creative task became selecting, rather than materialising, forms.

TarraWarra’s exhibition narrative, which kicks off after the first room laden with the London-Paris drawings, is a graceful progression of Klippel’s assemblage techniques. As he aged, when his work threw up problems Klippel seems to have solved them through play. This feeling only grows as his later miniatures appear more and more toy-like. Klippel’s decades-long devotion to sculpture gives you the feeling that he was always making and never bored. His best work imparts that exhilarating possibility.

As we see Klippel’s frustration with method and materials being alleviated by his caches of junk, you sense his process becoming increasingly intuitive. Of his hefty late wood pieces, which legendary gallerist Geoffrey Legge insists on capitalising as the “Great Wood Sculptures”, Klippel noted that the found pieces he used were driven by “an incredible magnetism” and that “things would just gravitate”. This exhibition displays his profound visual and spatial intelligence, but when I write that Klippel isn’t a thinking artist, this is what I mean. Klippel is a member of the international, mystical, a-political division of modernism. Less a revolutionary, more an anointed conduit of gravity and mass.

Victoria is a PhD student at the University of Melbourne. Her research concerns printmaking in Melbourne during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. In 2013, she was the Gordon Darling Intern in the Australian Prints and Drawings Department at the National Gallery of Australia.