Ari Tampubolon, Symposia: This show is dedicated to K-pop girl group, TWICE. I love you.

Amelia Winata

Is it possible for institutional critique to be joyous? If we cast our minds back to some of art history’s seminal works of this “genre”—Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, Andrea Fraser’s Museum Highlights—we recognise a humorous aspect in them; but the humour acts as a foil for an underlying pessimism. For many artists, the institution is treated as black and white; it is either good or bad. But the reality is that our relationships with institutions is far more complex. Roxane Gay, the American feminist writer, summed it up beautifully when she said that, despite the misogynistic content of the large majority of rap music, she could not help but love it. Ari Tampubolon, a queer artist of Indonesian descent, loves K-pop (South Korean Pop) and minimalism, despite both having some serious problems.

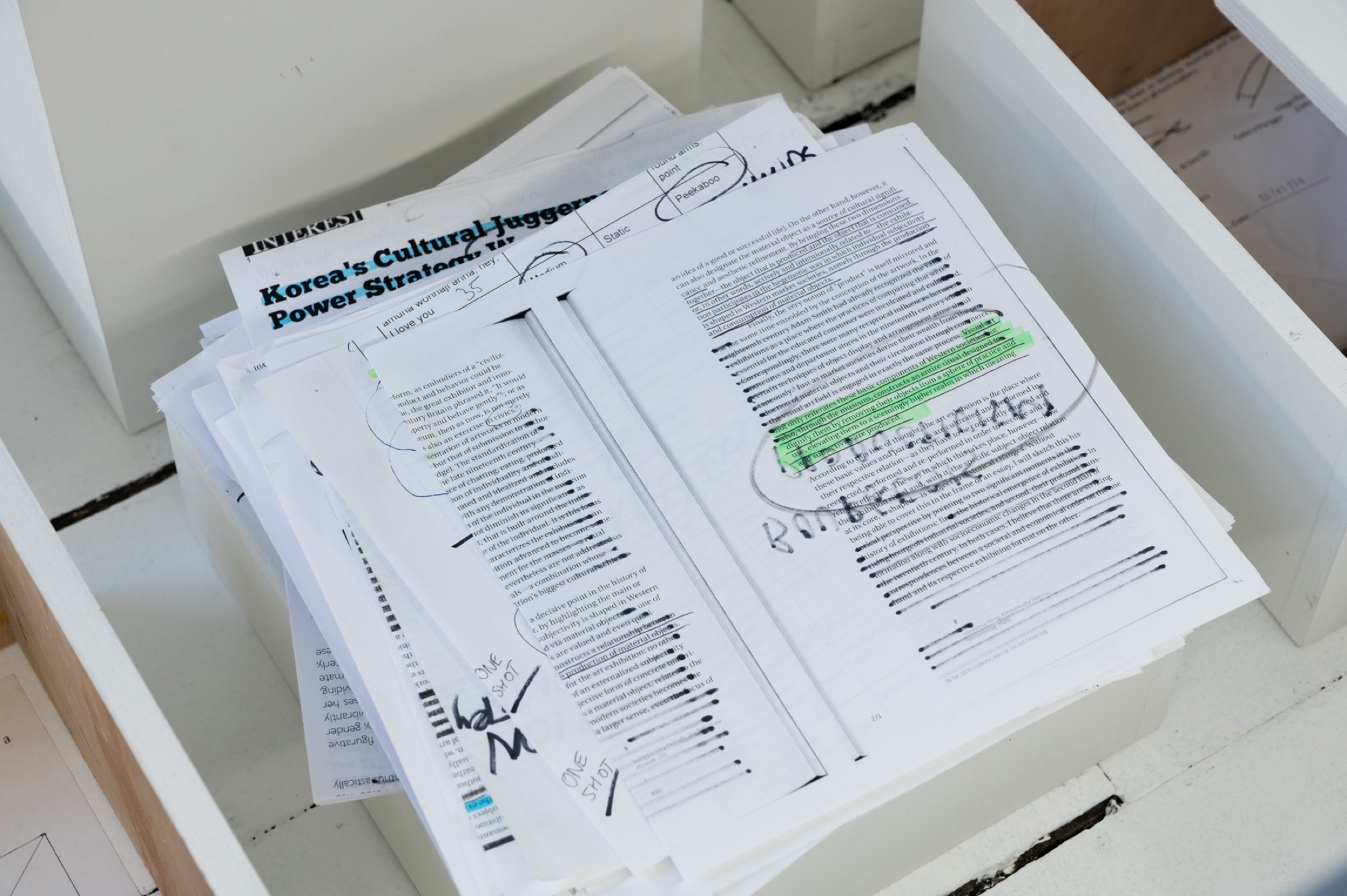

Symposia: This show is dedicated to K-pop girl group, TWICE. I love you is an installation in the small upstairs gallery of SEVENTH. The installation is a deliberately obvious reference to American minimalism. Nine white wooden boxes have been placed on the floor in a grid formation. They vary in height but are all quite low to the ground. The tallest box is about 30 cm high. Suspended from the ceiling, slightly higher than this grid formation is a square frame of white neon lights that illuminate the installation. It reminds me of Felix Gonzales-Torres’ light globe edged Go-Go Dancing Platform (1991); indeed, Gonzales-Torres was the quintessential post-minimalist identity politics artist. Many of the boxes contain documents related to the exhibition process. But the most compelling aspect of Symposia, is a 3:33 minute video titled Exegesis: You make me feel … special. In the video – which is presented on an iPad that sits atop one of the white boxes—Tampubolon lip syncs and dances to K-pop girl group TWICE’s 2019 hit Feel Special. I recognise the gallery I am standing in as one of the video’s backdrops. And as I continue to watch, I realise that the entire video was shot in SEVENTH. A pang of nostalgia hits me when I see the gallery courtyard where I spent many opening evenings at the gallery—one of the longest running ARIs in Melbourne and the only one in Fitzroy to have survived.

The three central themes in Symposia—institutional critique, minimalism and K-pop—are seemingly odd bed fellows. But if we consider that both K-pop and minimalism are institutionalised cultural phenomena, then the connection becomes easier. Tampubolon cleverly acknowledges that these are two institutions with very problematic histories that nonetheless appeal to their viewer/consumer. In the process, the viewer/consumer’s ethics are muddied. The general white, heteronormative structure of minimalism is the movement’s obvious flaw. In its purest form, American minimalism (Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre) recorded the experience of art “viewing”, taking it from the purely visual to the corporeal. That the viewer’s body became an intrinsic part of the experience of art was ground-breaking. But the question of who this viewer was remained a sticking point. Indeed, as the argument goes, minimalism presupposes a single viewer “outside history, language, sexuality, and power”, in the words of Hal Foster. A more contemporary understanding of this reading would be that minimalism ignores the nuanced world-views held by marginalised identities – LGBTQI+, diaspora, disabled – and presumes, instead, a very heteronormative, patriarchally predetermined viewer.

Meanwhile, K-pop’s problems are innumerable. The industry is notoriously gruelling for its stars. The fandom surrounding K-pop—known as K-pop idol culture—verges on the psychotic. Popstars are required to do just about anything to live up to fans’ expectations. Most stars are banned from dating to maintain a sense of availability to their fanbase. They are also largely restricted from speaking out on pressing issues such as feminism, human rights or mental health. In recent years, several high-profile stars have committed suicide due largely to the massive strain caused by extreme public exposé; the lack of privacy and pressure to perform. In 2017, Sulli, a member of the girl group f(x), took her life after internet trolling became unbearable—especially so after she joined a feminist campaign that supported not wearing bras. The process of training a K-pop star largely involves years of intense bootcamp-like living where the stars co-habit and work together before being launched to the public. Stars are also routinely expected to undergo cosmetic surgery and submit to a rigorous fitness regime. Finally, by the time most K-pop stars reach their thirties they are discarded by the industry that has been training the next big thing to replace them. In almost every aspect of its being, K-pop is completely unparalleled by Western celebrity culture.

And despite all of this, I still profess a love of K-pop. This is a guilty love given the industry’s near moral bankruptcy. Tampubolon, meanwhile, is obsessed with K-pop. Symposia is a joyful complication of the cultural structures of control. And, as such, it is a refreshing take on institutional critique that, so often, presents as a one-dimensional criticism. The institution is the institution, largely because we subscribe to it.

If American minimalism refused the monumental through a creation of a relationship between the body and the sculpture, then Tampubolon’s plinths produce a sense of humility. Watching the video on the short plinth forces the viewer to bend towards the ground, arching their neck past the LED frame towards the small screen. It is not a group experience. Headphones are available to one person at a time. The effect of watching the tiny screen, close to the floor and being the only one to hear the music is intimate. If K-pop offers a (false) sense of connection between fans and popstars, then Tampubolon mimics this in the cocoon that they have created with the small screen and headphones.

TWICE, who Tampubolon pays homage to in Exegesis, is a nine-piece group formed by the 2015 reality TV show Sixteen (the Korean version of Australia’s dearly departed Popstars). In a few scenes of Exegesis, Tampubolon performs the choreography for Feel Special with friends of Asian descent. In Western countries, the extreme fandom that TWICE has encountered stems from a large Asian diaspora fanbase that sees K-pop as a genuine leveller of cultural representation. The video is a homage. When, in the show’s title, Tampubolon professes “This show is dedicated to K-pop girl group, TWICE. I love you”, they are sincere. This adoration is palpable in the video. Filmed shot-for-shot with the original film clip, Tampubolon’s mastery of the group’s dance moves is impressive. What is crucial is that Tampubolon has managed to mimic the sense of absolute euphoria that K-pop videos embody, the effect of which is that the viewer is momentarily invited into a fantasy world of indulgence and joy.

While in Korea K-pop has been a huge cultural phenomenon for decades, its popularity has recently spread with great speed to Western countries. TWICE’s “boy-band” counterpart BTS, for example, recently went on a press tour of the USA, appearing on popular television shows such as Jimmy Fallon’s The Tonight Show and Saturday Night Live to extreme American fanfare. That Asian music suddenly has such a tight grip on Western culture is exciting. For many people of the Asian diaspora, K-pop offers significant representation; representation that is not only acknowledged by Western culture, but which eclipses it. Now instead of Asian celebrities supporting Western main players, the tables have turned. This was demonstrated recently on the BTS song Boy with Luv where the American pop singer Halsey was the support for the band. This comes after many years of Asian celebrities such as Jackie Chan cast as stereotypes, let alone almost zero non-English language music in Western music charts. Tampubolon’s excitement is wholly reasonable.

Symposia’s minimalist framing mechanism acts as the critical undercurrent that points to larger institutional problems. This is a difficulty that stems from a Western hegemonic framework, but that seems to have pervaded even Asian cultural phenomena as evinced by the topic of K-pop. Tampubolon has inserted various documents from the exhibition planning process into the installation, thereby demarcating the conditions of the institution within the institution itself. The artist’s exhibition agreement, plinth building specifications and the frame-for-frame plan for shooting the video lay bare the language that supports the gallery structure. Other plinths house research on soft K-pop and soft power, including a paper from the seminal political scientist Joseph Nye that Tampubolon has stuffed into a crack in the floor. These documents feel a lot more rote than the sculptural and video components of the work. But while they are the more flawed elements of Symposia, the concept of framing the institution within the work feels like a necessary critical counterpoint. I just wonder if they might have been executed in a subtler way.

That SEVENTH is the setting for the video adds another form of institutional framing to Symposia. It is also the work’s source of parody. Some of my favourite scenes in Exegesis are the motion blur shots of banal gallery markers, including the pasted-up paper signage that signals the upstairs location of the exhibition. It has always remained a mystery to me why K-pop videos use slow motion and cheesy 80s camera techniques when the rest of their styling is so up to date and cutting edge. But they do. And this is the formal technique that brings an innocent parody into Tampubolon’s homage. In fact, the slick choreography and accurate lip syncing seems hilariously out of place in the scenes where the gallery is obviously identifiable. But this satire does not negate the delight of the video; rather, it adds a layer of complexity.

If it feels like I have been going back and forth between descriptions of critical institutional analyses and descriptions of pleasure, it is because that is exactly the paradox that Symposia embodies. But this is precisely what makes the work, as a piece of institutional critique, so unique. Particularly for early career artists such as Tampubolon, the urge is to slam the institution without admitting that there are also appealing aspects of it that continue to reel us in. For those who were not able to see Symposia before SEVENTH’S temporary closure due to COVID-19 (the exhibition can still be viewed by appointment, if you are that organised), I highly encourage you to visit the YouTube video for TWICE’S Feel Special and experience the almost perverse sense of enjoyment that Tampubolon translates to Symposia.

Amelia Winata is a Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.