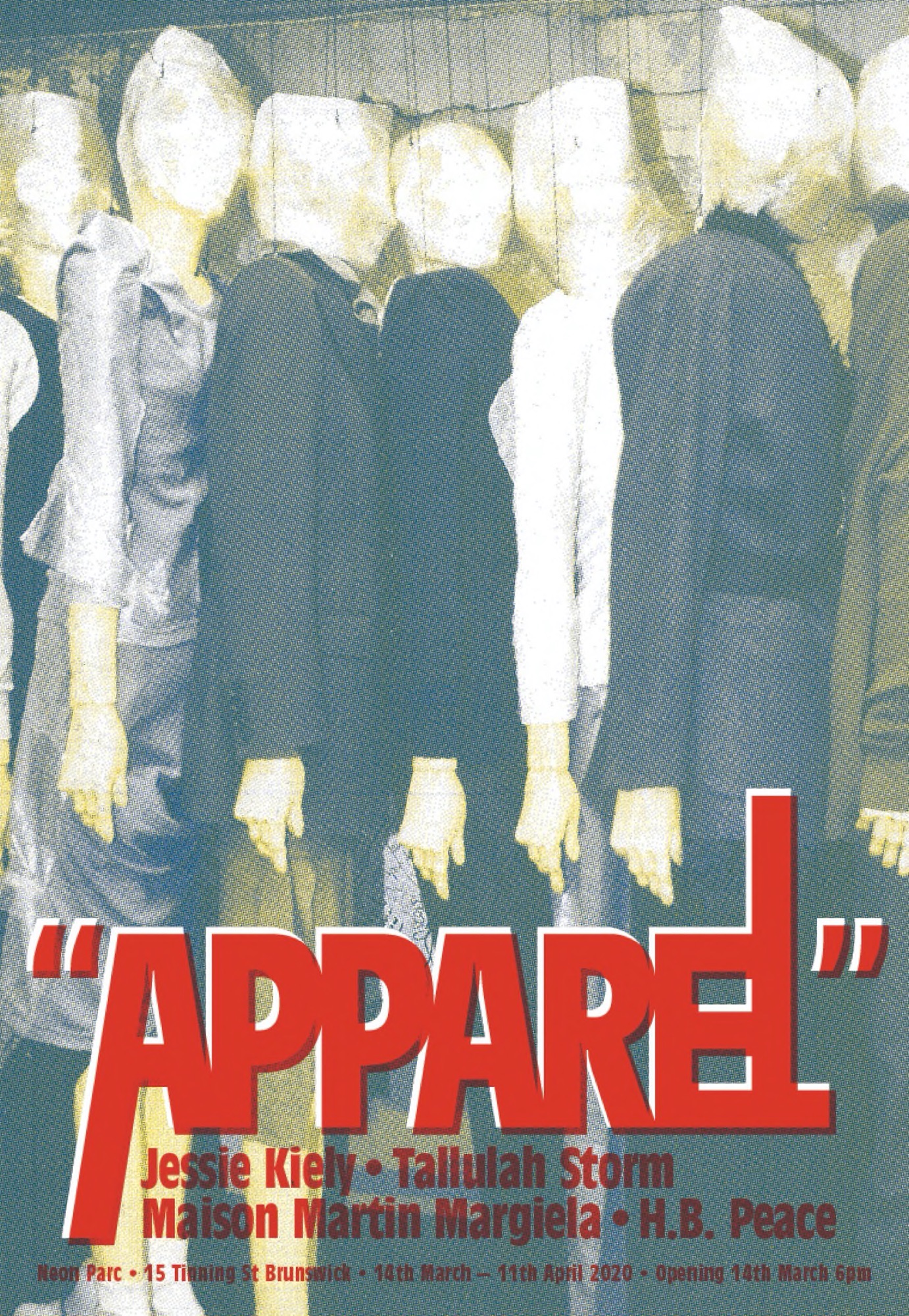

“Apparel”

Kate Meakin

The flyer for “Apparel” was thrilling in the vein of a vintage film poster like Jaws or Psycho—the title emblazoned in bold red letters against a grainy image. In this case, it is a photo by Anders Edstrom featuring Margiela-clad mannequins closely posed in line formation with heads muted by plastic wrappings. They appear like artefacts coming out of storage or a police line-up of de-identified women. They are in fact the models queuing backstage at the FW 98-99 runway presentation in which mannequins were suspended by string and paraded as lo-fi marionettes across a stage at Paris Fashion Week. The original photograph has a casual but atmospheric snapshot feel to it that seems to document the garments in backstage limbo, a means of advertising them in a state of zoned liminality—clothes, finally unfinished, suspended somewhere between elegance and formlessness, waiting to be reanimated on a real, live, chic body. Edstrom’s deliberately informal aesthetic was a fresh and vital voice in the glitzy arena of 90s fashion photography. Alas, the lo-fi fashion image is as familiar to the industry now as the high production studio shoot, so update the branding we must.

“Apparel” ’s poster choice re-calibrates the signature Margiela-masked subjects as disarticulated in the anatomical sense. Unambiguously gory girls, they are rendered closer to abject horror pastiche than they are aligned with the deconstructive fashion icon. In the exhibition text, curator Matthew Linde writes, “Reaffirming the acumen of Maison Martin Margiela in 2020 is almost gauche. The fodder for bad memes and museums, PR Deconstructor has instantiated itself at the very heart of corporate culture … ”. How to resuscitate the irreverent spirit of the Belgian designer’s creative legacy from the deathly carousel of ironic capitalism that rose from its ashes?Linde invites us to contemplate the aftermath of this distinctive oeuvre—haute garments derived from rag picking and reproductions—alongside the work of three young local designers: HB Peace (of Blake Barns & Hugh Egan Westland), Jessie Kiely and Tallulah Storm.

Entering Neon Parc’s long Brunswick gallery space, one is drawn towards a distant mise-en-scène of mannequins and plinths arranged in the farthest third of the room. The installation seems to resemble something between a theatrical dress rehearsal and a half-put-up museum show—the lights are off in the negative space of the gallery and the main event is lit by two spotlights whose tall black stands also demarcate the beginning of Liam Osborne’s pallid carpentry-cum-stage metamorphosis. Next to the lights, before the panorama of models, a black & white film of Margiela’s FW 97-98 presentation is displayed on an old TV monitor placed atop a chair and turned up on its side to allow a portrait display mode. The video depicts women casually walking through an audience of spectators on a Parisian street, dressed in clothes resembling toiles, accessorised with wigs made from fur coats (one of which appears in the show). A Belgian Brass Band plays a sombre tune that works to score the room with its echoing music and the nonchalant affect of the model’s anti-performance. In the gallery, we have twenty-seven outfits modelled by an eclectic cast of mannequins who vary in age, colour and texture. The casting could almost be a show within the show—a retrospective of figures.Some wear gracefully distressed wigs (made by stylist Penelope Burke), some are masked with paper or plastic à la mode MMM. Most are classically poised in a neutral standing position while others sit, flex, strike a pose or seem to be caught in the process of putting their dress on.

“All of Martin’s clothing put everything else out of fashion”, quips Carine Roitfeld in the 2019 documentary Margiela: In His Own Words. This compliment reveals the cruel logic of how the fashion system consumes style, where innovation is quickly wed to commercialism.In this logic, to put himself in fashion as an “outsider”, Margiela supposedly put other “insiders” out. Being “in” grew weary for Martin; after twenty years he got “out”, putting his clothes back where they came from—out of the market and on to the vintage rack. This exhausting rhythm of innings and outings is embedded in the construction of his artisanal garments. An assortment of red pleated vintage skirts reassembled into one, and a corset made from fused together black leather gloves (both Artisanal SS, 2001), open “Apparel” as the most literal examples of Margiela’s Midas touch. The verbal description of this look could easily summon the image of a tragic Etsy creation, but in Margiela’s skilled hands (or the many hands of his studio) a sophisticated silhouette is drawn that feels both highly finished and permanently undone. Bringing the “out” back “in” is an old trick in the fashion book, but literally using old things still remains rare in high fashion. Moving through the space we see variations of this touch—the polyester lining of a vintage dress becomes the outer shell, couture garment labels are re-worked into a top, vintage slips and dresses are cut up and spliced together to form new gowns. The garments built from scratch carry the effects of these material studies—the knitwear is distressed or dyed to look desirably faded, a stylish winter coat is designed to look like a duvet. These garments are beautiful because they are charged with an erotics of irony, rather than a cynical smile. A skirt sewn from recycled silk scarves (Artisanal SS, 1992) still has its care instructions attached, reading: “This creative process ensures the uniqueness of each piece and intentionally encompasses the characteristics of passage of time and use normal for source materials of this nature”. The inevitable demise of the materials is built into the garments—by acknowledging their transient place in the system of consumption, they are timeless.

So how can we pull the spectral thread of MMM through the works of the others? Most explicitly, it is channelled via the only garments present that were created specifically for this show—the ghost dress ensembles by HB Peace. Three silk jersey gowns, in beige, cream and fluoro yellow, completely engulf the figures they adorn in homage to the signature Margiela mask and the most expedient of Halloween costumes—the bed sheet turned ghost. The masked face was originally introduced by Margiela for runway presentations as a means for pulling the viewer’s focus towards the movement of garments on the body erasing the distraction of the model’s possible subjecthood. While the ghost dresses seem to revive a “body as canvas” effect, the white cotton organdie suit jackets worn over them (which were replicated from found jackets in HB Peace’s 2016 collection “Col Gunavatta Kupfer”) seem to invert the clothes to instead be a canvas for the body. Organdie is a white papery cotton traditionally used as lining to stiffen sculptural garments. Fixed on the exteriors of these jackets, it is incredibly prone to creasing and staining, meaning it is impressed on by its owner from the moment it is worn. The jackets are markedly soiled with human wear at their cuffs and collars—one in particular has a series of brown markings across the back as if wine had been spilled across it several times. The inclusion of their owner’s names on the materials list—Chantal, Laura and Ricarda—further personifies them. Here, the concept of “wear” as a means of design is furthered.

The conditions of marginality that Margiela’s garments explore are in some ways inherent to the format of the graduate collection, which exists in the liminal zone between proposition and product—a collection devised for an imaginary market. “Apparel” presents us with works from two recent RMIT graduates who consider the slippages of “ready to wear” garments.

All the silhouettes in Jessie Kiely’s 2017 master’s collection were built from an original 1970s workwear dress she found, redrafted and extorted into a new series of looks. The resulting garments present exaggerated interpretations of feminine tropes of office-wear and the evening dress. The repetitive reworking of the “tube” form in this series works to articulate the cyclical nature of the fashion system. The tops of these long-sleeved shirt-dresses alternate between buckling-up or down in accordance with the styling of their identical boxy black tube skirts. The fixed poise of these stark, weighty bands of maxi skirting conceal the figure beneath. The effect is one of frivolous modesty, except in the mini-dress iteration, which seems like it could have been a longer garment that was decidedly pushed up at the last minute to be more revealing. There is a demure absurdism to this dress that celebrates the moment where formal restraint slips into unconscious release through the performance of wearing.

Tallulah Storm’s 2018 honours collection presents reconstructed silhouettes of archetypal garments such as jeans, the woollen coat and the slip dress. In the context of this show they almost appear as diffusions of Margiela’s designs, but with a more girlish, abject accent that shifts them to a different, more delinquent register. One dress, for example, presents as an elegant loose hanging velvet mustard slip from the front, but when turned to the side a jarring hot pink children’s duvet printed with a playful pattern protrudes from the scooping back line. These garish duvets annotate most of Storm’s garments, sometimes accompanied by a naive illustration-cum-label that seems to irritate more than embellish the garments. The most poignant accessories in this collection are the jewellery pieces that adorn these looks. Bracelets and necklaces deriving from stolen stashes of eclectic op shop chains that have been fused and tangled together to look like accidental assemblages. These fine, glimmering ornaments emphasise their construction process as the key design feature, striking a perfect balance between nonchalance and ingenuity.

While there are twenty-seven looks in the gallery, there are actually twenty-nine mannequins in the room—an additional two remain off the list of works because they are undressed, but their presence, like the best accessories, feels essential to underpinning the overall ambiance of the scene. One barely registers as a model. It is the only headless figure in the room and resembles an aged bird cage constructed in the hourglass shape of a woman’s figure in a floor-length wire gown. The wires are bent open at the base of her skirt as if a small creature has forcibly escaped. The other, who appears to be the oldest, plumpest mannequin (by comparative standards to the other girls), is placed alone, facing the wall. With unkempt hair, pitiful pantyhose, strangely articulate hands and a face that might once have projected a tranquil doll-like beauty, she now fades into broken anguish. Like Marlene, the tormented, submissive assistant in Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, she bears silent witness to the wigged protagonists that surround her—their parade of unhinged glamour and neurosis ever apparent. There is a gimmicky pathos to the presence of these naked figures, which reverberates in the horrific melodrama of the exhibition’s flyer. “Apparel” here nods to the poignant use of mannequins in the sparse, tableau vivant installations of Irish artist Cathy Wilkes. Where Wilkes might dramatise the hollowness of the mannequin as a sincere instrument for exploring the empathic potential of art, Linde casts these figures as a team of uncanny workers aware of their use value or diminishing potential.

Collectively, these elements form an exhibition that implicates not only the garments, but all the elements that support them as part of a self-reflexive design process. It is the material gestures of revival rather than the cynical declarations of exhaustion that resonate from this show. These garments desire to go beyond themselves in want of a second life, not a second death.

Kate Meakin is an artist based in Melbourne.