Anne Wallace: Strange Ways

Tara Heffernan

Over the decades, progressive politics has believed in continuing social improvement and change without end. Its neglect of the human need for belonging … has created a bourgeois left that is deracinated … (and) poorly equipped to address the questions now confronting its own children about the nature of adulthood, and the meaning and purpose of life …

—Jonathan Rutherford, “How the decline of the working class made Labour a party of the bourgeois left”, New Statesman (2018).

And when you want to live, how do you start? Where do you go? Who do you need to know?

—The Smiths, “The Boy with the Thorn in His Side”, The Queen is Dead (1986).

Currently on display at the Art Gallery of Ballarat, Strange Ways is a retrospective of Australian artist Anne Wallace’s three-decade painting practice curated by Vanessa Van Ooyen. Though incredibly diverse in style and subject matter, Wallace’s figurative paintings are united by a slick, advertisement-like aesthetic and preoccupation with post-war iconography. Wallace’s work was recognised early in her career. Many paintings exhibited in this retrospective are from the 1990s when the artist was in her 20s. Echoes of Giorgio de Chirico’s eerie architecture and elongated figures (which also bear similarities to Australian modernist Russell Drysdale’s work) populate these early paintings. These are also the most transparently embedded in adolescent anxiety, as epitomised by Exemplar (1993) which depicts three young women forming a neat half-circle around a towering matriarch. Each clutches behind her back an object of entertainment—a toy airplane, a slingshot and a bundle of books. In another painting of the same era, we see a similarly rigid representation of schoolyard discipline: Untitled (1993) shows a group of male figures, wiry with adolescence, pacing in a circle, heads bent toward open books. Though Wallace has refined her painting technique in the decades since these works were produced, an adolescent tone carries throughout her oeuvre, portentous because it is not entirely nostalgic or reflective. Rather, it conveys a sense of arrested development—a perpetual investment in the emotions, fantasies and cultural preoccupations of youth—that is increasingly ubiquitous today, spurred by a society in which the promises and expectations of traditional adult life are becoming less attainable.

Strange Ways takes its name from Strangeways, Here We Come, the fourth studio album of English post-punk band The Smiths. Wallace has expressed a particular affinity with lead singer Morrissey. Her senior by just over a decade, Steven Patrick Morrissey was born in Manchester in 1959 to working class Irish immigrants. His adolescent experiences—from the humiliation he suffered at the hands of authoritarian headmasters and the nights spent idolising pop musicians and poets alike from the dreary bedroom of his family’s council house—informed the lyrics he later sang in the 1980s with The Smiths, a name the band chose for its utter ordinariness. Like Wallace, his work is deeply embedded in the fantasies and anxieties of adolescence. For both, the family home is a site of significance: simultaneously a stifling, repressive environment and the sanctuary in which creativity and hope blossom in the adolescent mind, sheltered from the damages of the real world. This dualism is conveyed by paintings like High Windows (2010) and In My Room (2007)—likely a reference to the 1963 Beach Boys song of the same name—which are cleverly installed side by side. High Windows depicts a rope crafted of knotted bed sheets extended from a partially open window (a fantasy of adolescent escape). In My Room represents the interior—a rather bland scene comprising a bed, a lamp affixed to the wall above it and a framed picture of a dinosaur (quaintly, the bed sits just slightly off-centre). The mundanity of the space reveals nothing of the fantasies of its occupants. To quote the Beach Boys, “There’s a world where I can go and tell my secrets to, in my room, in my room ( … ) Do my dreaming and my scheming.”

Though Wallace is a member of Generation X (those born roughly between the early 1960s and late 1970s), her work doesn’t feel defined by a particular generational aesthetic nor does it appear dated (at least, not in a negative way). Her more mature works (those produced from the late 1990s onwards) recall, in iconography as well as style, the American photorealist painters of the 1960s and 70s. However, they also evoke the contemporary idealisation of the “retro”, partly driven by the eclectic aesthetic sensibilities of image-based social media platforms like Tumblr and Instagram. These connections are, however, inadvertent—or perhaps prophetic—as much of her oeuvre predates these websites. Similarly, while the presence of houseplants in her domestic interiors (Sansevieria trifasciatas, or, mother-in-laws-tongue, are common) might have seemed dated fifteen years ago, a staple feature of the 1970s homes of the artist’s childhood, today there’s a resurgence in their popularity due to green-thumbed millennials confined to apartments or sharehouse bedrooms.

As noted by writers like Jonathan Rutherford and Angela Nagle, adolescent preoccupations have in the past decade gained greater meaning for a generation whose transition to adulthood has been stunted. For those who have come of age in the twenty-first century, the traditional expectations of adult life are becoming more and more unrealistic. Rising unemployment, increased casualisation of work and job precarity mean dreams of home ownership, exiting the rental market and starting a family are often delayed. Even maintaining a long-term relationship, easily compromised by the growing instability of contemporary life and its attendant technologies, has its challenges. As a result, adolescence is prolonged. Hobbies traditionally entertained by children—video games, Cosplay, Lego and obsessive fandom around bands, film and book franchises—now occupy many long into adulthood and provide great meaning and structure to their lives in lieu of familial responsibilities and fulfilment. These communities even engage in serious discourse regarding their politics and internal hierarchies—the darker side of which was demonstrated by the Gamergate controversy in the mid-2010s.

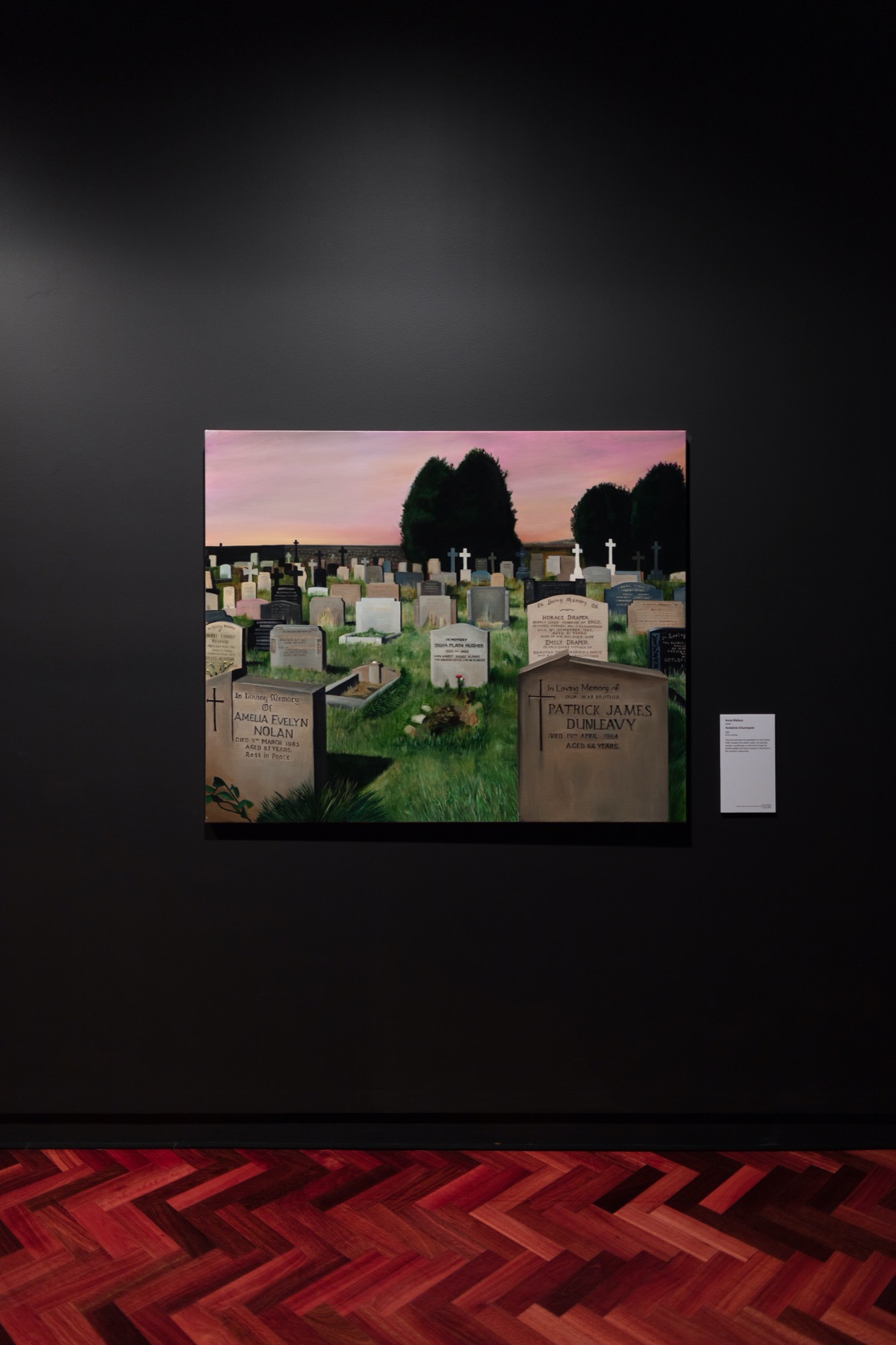

Prefiguring this state of perpetual adolescence, many of Wallace’s paintings reference song lyrics, musicians, artists or poets. Often, even the act of consuming culture—or the particular ways we interact with cultural products—is deemed worthy of representation. Resembling a travel shot on a “sad girl” Tumblr from the 2010s, Yorkshire Churchyard (2001) depicts the grave of American poet Sylvia Plath, a writer who has a particular appeal to young female introverts. Returning to the domestic environment, Dreaming of a Song (2005) shows the exterior of a house. A curtain pushed to the side reveals a partially obscured figure clutching a vinyl record—an auratic object that appears in many of Wallace’s works, including Vinyl (2004) which shows a couple intertwined on a couch in the background, their figures blocked out in the shadows. The focus of the painting is not the couple but a record player with the sleeve of Roxy Music’s Avalon resting beside it. Even when musicians are represented, as in the portrait Grant McLennan and Robert Forster: The Go-Betweens (2001), there is a nod to the lineage from which they are drawn. A book in McLennan’s hand is titled ‘An Italian Poet From The Thirteenth Century’, referencing lyrics of Bob Dylan that speak of the intimate relevance of a collection of old poems. How we understand ourselves, filter or describe our emotions through music, art and literature is a consistent preoccupation of Wallace’s practice.

It’s important to note that, while the objects Wallace represents (books, vinyl records and record players) are still produced and in use, cultural consumption no longer requires them. The presence of streaming services, eBooks and YouTube have rendered the objects themselves inessential. Certainly, people still buy books and records, often claiming to prefer them. However, these items are also purchased as a prize or token for display or novelty. Echoing Wallace’s retro iconography, the past fifteen years has seen an increased interest in nostalgia-heavy entertainment media. Examples include series like Mad Men (2007–2015), Stranger Things (2016–) and Dark (2017–2020) and films such as The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012), It Follows (2014) and It (2017). Importantly, the rise in popularity of these nostalgic projects is roughly concurrent with that of high-speed internet access. (For context, between the years 2000 and 2020, the percentage of adults with internet access in America jumped from 52% to 90%). Though it’s tedious to lament a “simpler time” before the internet, there is a “slowness” to previous practices of cultural consumption, and romance to the materiality of cultural objects, that seems to be celebrated in these examples (and in Wallace’s paintings). In a tender scene from sci-fi series Stranger Things, set in the 1980s, teenager Jonathan Byers introduces his kid brother to The Clash after he happens to hear “Should I Stay or Should I Go?” playing on the car radio. They sit together on the bed watching the record spin while bopping their heads to the beat. In a similar scene from the film The Perks of Being A Wallflower, set in the early 1990s, the main characters are awestruck when they happen to hear David Bowie’s “Heroes” on the car radio, a song which none of them recognise. There’s no Shazam or Google to help them out, so the teenagers have to relish the moment, diverting their drive home so they can cruise a favourite scenic route while the song plays out. For the rest of the film (the artist and song title aren’t discovered until the end) they refer to it as merely “the tunnel song”. These scenes convey a sense of adventure and discovery. They emphasise the ritual of cultivating cultural taste which, in the past, might have taken a great deal of time and energy. Conversely, today, a whole world of music, film and literature is just a click away.

In a 1985 interview, while speaking of his childhood, Morrissey describes himself as a “back bedroom casualty”. He explains:

I spent a great deal of time sitting in the bedroom writing furiously and feeling that I was terribly important and that everything that I wrote would go down in the annals of history, or whatever.

He adds with an infuriating smirk, “And, um, it’s proved to be quite true.” A similar presentiment is expressed by Wallace in a filmed interview playing on a loop in the gallery. Recounting her early exposure to a collection of Dylan Thomas’s stories found on her parent’s bookshelf, Wallace explains:

When I read that, I thought, this was absolutely amazing—I wanted to be like Dylan Thomas (… ) I put a lot of pressure on myself to become an artist and make a lot of work by the time that I was twenty.

Though lacking the grating arrogance of Morrissey’s aforementioned comment, this statement also proved to be quite true. These pronouncements, imbued with the belief in the importance of one’s own words (or cultural output), may have been synonymous with an artistic disposition in the twentieth century. The artist sufficed as a cosmopolitan character deeply appealing to a young person from a sheltered suburban environment. Today, however, with the ubiquity of social media, professional networking sites and dating apps, there’s an insidious pressure on all young people to maintain an online presence and public image—to see themselves as important and their opinions and hobbies worthy of documentation, attention or even adoration. These social pressures and hierarchies are, moreover, not tied to phases of adolescent uncertainty, but propel professional and social life. Boris Groys has described this condition in his essay ‘Self-design and Aesthetic Responsibility’ as a mass cultural practice of neo-liberal society. No longer is it just artists and celebrities who need to cultivate an image and persona—today “everyone is expected to be his or her own author”, presenting themselves as a product subject to external evaluation. This is not solely driven by narcissism, as is often claimed, but by the need to maintain an online presence in the increasingly competitive job (and dating) market. Though we might wonder whether everyone truly has to abide by these rules, they are certainly becoming more ubiquitous for younger generations.

Both Morrissey and Wallace are, however, artists in the traditional sense of the word, not human products shaped by self-design. But the perpetual adolescence of their work, and the attendant investment in ideas of greatness, prefigures the normalisation and legitimisation of such behaviours and illusions in the world of adults. The obsession with entrepreneurial figures might be one of the most grotesque and unromantic contemporary mutations of this. (Elon Musk is case in point!) Today, the pitiful self-loathing of Morrissey, and the misogynistic undertones of his tales of romantic rejection and longing, seem at home with incels (involuntary celibates). These are men who might spend a comparable amount of time in their bedrooms, but are not alone. Instead, they are united online by a shared distrust of women—the toxic by-product of an increasingly atomised, but nonetheless networked society. Lonely girls of the digital age might still be reading Sylvia Plath, but the abundance of fierce Instagram poets and cut-throat feminist Twitter personalities may take precedence. For both Morrissey and Wallace, their early artistic development was cocooned by the home. They were not a viral tweet away from total annihilation, but largely disconnected from the outside world aside from their books, television, radio and home phone (all likely monitored, to some extent, by a parental authority). In other words, for better or for worse, they were alone in a way that is no longer possible.

In one of Wallace’s more disturbing paintings, Writer’s Block (2000), the comforting monotony of an interior scene is disturbed by the presence of a vulture (perhaps taxidermied?) emerging from behind a houseplant. Who is the vulture? What does it mean? At first glance, it might seem to be a bad omen, perhaps a reference to the artist’s fear of becoming washed up or obsolete. However, while the bird of prey is known as a scavenger that feeds on decay and preys on weakness, it also possesses many positive connotations related to resourcefulness and renewal, a pertinent dualism at this point in history. Perhaps the artist is the vulture, able to perpetually reinvent and revamp strange scenes of bygone domesticity and adolescent projection, transforming the mundane into the profound?

Strange Ways is a touring exhibition first held at the Queensland University of Technology’s Art Museum in Brisbane. It’s scheduled to travel to the Samstag Museum of Art in Adelaide after completing its run in Ballarat (where its opening, initially scheduled for March, was postponed to 1 July due to the COVID-19 lockdown). I saw Strange Ways two days after the gallery reopened, one day after my neighbouring postcode returned to lockdown and less than a week before all of metropolitan Melbourne followed suit. You might not get to see it, but you can easily look at pictures online.

Tara Heffernan is a PhD candidate (Art History) in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. Her thesis concerns the work of post-war Italian artist Piero Manzoni—specifically, the political and cultural dimensions of his employment of humour and transgression in relation to capitalist aesthetics. Heffernan’s broader research interests include politics, feminism and the lineages of modernism and the avant-gardes in contemporaneity. She has published in Third Text Online and regularly contributes to Australasian art publications such as Eyeline and Artlink.

In the interests of full transparency, Rex Butler, one of Memo Review’s founding fathers, is married to Anne Wallace. Rex had no knowledge or involvement in the commissioning, writing or editing of this review!