Angelica Mesiti: ASSEMBLY

Amelia Winata

Angelica Mesiti’s sumptuous three-channel video ASSEMBLY takes democracy as its central concept. Curated by Juliana Engberg, the work slickly weaves together the artist’s trademark vehicles of music and non-verbal language.

This is the third time that Denton Corker Marshall’s black box pavilion has housed the Australian exhibition in the Giardini. 2017’s offering, My Horizon, from Tracey Moffatt and curator Natalie King, was an exhibition of photographs and videos that bore little relationship to the architecture of the pavilion. Mesiti and Engberg present Moffatt and King’s antithesis, working with and augmenting the architecture of the pavilion to produce a magnificently slick, site-specific installation.

To achieve this, a floating floor was installed over a pre-existing architectural focal point: a central, sunken ‘amphitheatre’—designed to mimic the architecture shown in the video—that audience members are encouraged to sit around to view the video work that is distributed across three enormous projections that surround the amphitheatre. The installation is flawless. Even if the mechanics behind it are quite complex. French architect Simon de Dreuille was commissioned to design the floor, while a specialised team headed up by Gotaro Uematsu and Simone Tops were on site months in advance to overlook the installation of the videos. Little was left to chance. And it shows. The exhibition is unmistakably a product of Mesiti and Engberg; it is a display of Mesiti’s ethereal and poetic beauty mediated through a restrained display of emotion that Engberg often displayed in exhibitions curated during her time as artistic director of ACCA.

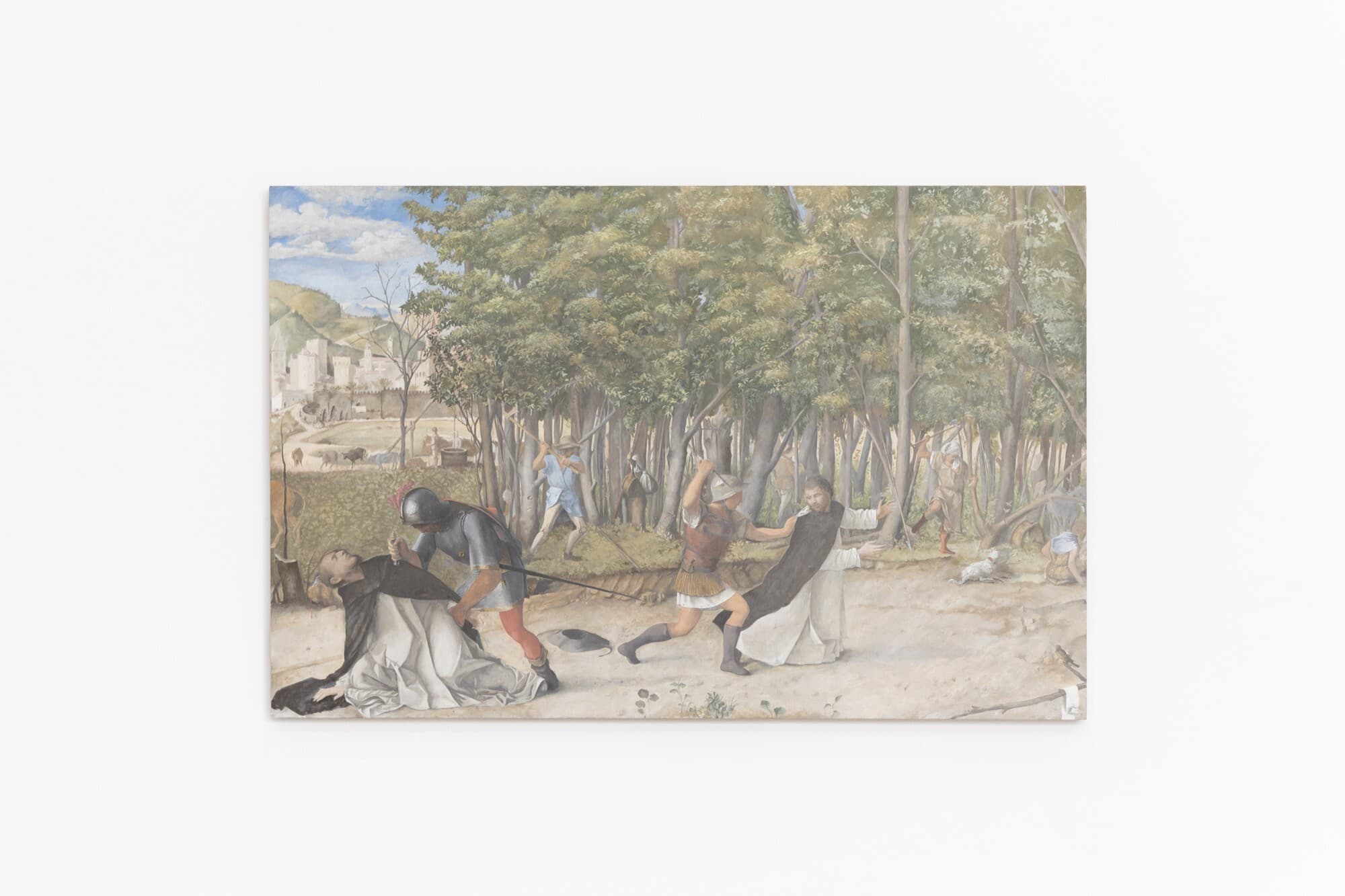

The video component of ASSEMBLY is set across two locations: Parliament House in Canberra and the modern-day Senate in Rome. A very loose narrative is developed around David Malouf’s poem “To Be Written in Another Tongue” which, at the beginning of the film (video throughout), is coded by a Michela machine, a 19th century stenographic device based on a piano keyboard that is used to record proceedings in the Italian senate. Malouf’s poem is written from the perspective of a well cultivated worldly individual: “Giotto’s tear-stained kamikaze angels”, “some grey Jardin des Plantes”. The video, too, features performers from various cultural backgrounds, all acting in harmony, a reflection of the cosmopolitan image that biennales promote and indulge themselves in. The text is then coded a second time: as a composition written by Max Lyandvert that we see performed in these parliamentary settings by various musicians. A violinist, a clarinettist and a pianist are introduced one by one, each on separate screens. The music builds up to a restrained crescendo. In subsequent scenes, split across the three channels, we see beautiful long shots of a Lebanese drumming group, a youth choir, a choreographer signing protest language, stills of the deserted parliaments and extreme close ups of murals depicting ancient Roman parliaments on the walls of the architecture.

Despite the multitude of actors and the variety of scenes, the film is extremely slow-paced. Many scenes are so unhurried that they might be mistaken for stills, an ambitious undertaking given the limited patience of audiences particularly in the oversaturated Biennale setting. Add to this the fact that the film is 25 minutes long and it becomes apparent that Mesiti and Engberg were unwilling to compromise. The first time I viewed ASSEMBLY was in a preview with just a handful of others. In this context, we were able to sit with the work from start to finish completely uninterrupted. My second viewing was during the vernissage week when endless rabbles of people were constantly moving in and out of the pavilion. As if democracy is disruption, the experience after my very privileged first viewing was admittedly challenging, particularly given the fact that the audience sits in the circle of the artificial amphitheatre. I was unavoidably facing other audience members who rarely sat still and who rarely paid attention for more than a couple of minutes. ASSEMBLY would therefore benefit from order, with staggered viewing sessions to allow people to see the work uninterrupted by each other.

While ASSEMBLY explores the concept of music as a uniting feature of humankind, critical visual cues also emerge. Mesiti, who is infamously meticulous, has used a controlled colour palette on a large scale to produce an extremely opulent outcome. The same red carpet seen in the on-screen senates covers the entire artificial floor, creating a continuity between the images on the screen and the exhibition space. By extending the red carpet out into the exhibition space, Mesiti places her audience in extreme proximity to the ceremony that red carpet has long signified. But why does Mesiti want her audience so close to this ceremony?

Other scenes are warm, almost glowing. For example, a choreographer dressed in warm shades of brown moves around a room with similarly toned furniture—a chestnut brown velvet sofa and golden drapes become the sensuous backdrop for the dancer’s hand gestures originally developed by protestors during the 2017 Nuit Debout demonstrations in Paris. The silence and gaps offer the most gravitas, suggesting that negation sits at the heart of the work. Acting within the architectural tropes of traditional democracy, the dancer recodes the site by way of a nascent language derived from but in opposition to these ancient systems. The combination of warm imagery and silence has a somewhat perverse Zen quality; we feel cocooned by representations of a system that has increasingly disappointed us. Are we to be seduced by these interventions, drawn into the houses of democracy?

These questions provoked both a bodily response—warmth and security—and an intellectual response that told me that democracy is totally at odds with itself today.

In a short text written to accompany the work, curator Engberg states that the “exuberant energy (Mesiti) unleashes demonstrates the creativity and strength of community and communality at a time when ‘Democracy’ is under strain—fragmenting and failing.” Of course, the work is just that: a wistful, decadent image of unity as a metaphor for a democracy that feels impossible. There are certainly hints that Mesiti understands the pitfalls of a democracy that has high regard for the aspirational myths at its historical origins, which she depicts through murals of ancient parliaments: a subtle compare and contrast, if you will.

Implicit in this discussion is the symbolic nature of the architecture. Invariably, this extends to a consideration of the “democratic processes” that bring the Australian pavilion into being. In an article written by Ann Stephen in Third Text about Richard Bell’s shortlisted entry, Stephen outlines how the process for selecting the participating artist for the Australia pavilion has recently changed from a closed invitation system to an open proposal system. Stephen calls it a “more democratic order” that has nonetheless been critiqued for favouring particular artists and gallerists based upon prior relationships with existing members of the board and selection panel. She observes that Bell desired to undermine the nominally “democratic” nature of the selection process by chaining up the Australian pavilion and presenting it—as Australia presents itself to refugees travelling by boat—as a space that is inaccessible. Bell then exhibited his ongoing work EMBASSY outside of the official confines of the Biennale, off-shore at the nearby Certosa island. Locating the pavilion as the symbolic site that presents a skewed vision of democracy, Bell had hoped to completely block access, highlighting the imbalance of power that architecture can embody. Bell was present during the vernissage, erecting EMBASSY in the Giardino della Marinaressa and having a dwarfed and chained version of the Australia Pavilion driven up and down the canals. Even in this form, the pavilion was instantly recognisable, a fact that underscored the symbolic position that it wields as the representative of particular national interests at, according to Bell, the exclusion of others.

My aim here is to highlight the way in which architecture, as the sight par excellence of contested democracy, folds in on itself. Mesiti’s work explores this thematic by literally inhabiting the sight of democratic contention. If Bell’s architectural intervention was to bar access to the Pavilion altogether, then Mesiti’s intervention masked the Pavilion as site of contested access. ASSEMBLY therefore presents an exacerbated illusion of democracy that seeps from screen to exhibition space, leaving the viewer to inhabit the artificial amphitheatre in a dream-like manner. For Mesiti, the Pavilion is a stage set for democracy to romance us with the symbols of its architectural power. Mesiti remains elusive on her position in relationship to democracy, saying she is more interested in creating provocations than presenting opinions. But ASSEMBLY, at minimum, joins an ongoing discussion in the international art circuit about what alternatives to the pre-ordained and admittedly ancient forms of democracy might look like in a contemporary context. While constructing a form of idealised democracy on-screen, it might be said that Mesiti simultaneously deconstructs the supposed “democracy” that representative governments embody in 2019.

Amelia is a Melbourne-based arts writer and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne.