Andy Warhol and Photography: A Social Media

Caitlyn Lesiuk

It’s hard to get excited by another Andy Warhol retrospective. Since the artist’s death in 1987, there have been seemingly endless attempts to frame his place in twentieth-century art and aesthetics, mostly taking place in the US, and culminating in the Whitney Museum’s 2018 to 2019 retrospective. What could an antipodean showing possibly add?

Warhol and Photography: A Social Media, currently on view at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), shows there is still more to be said. It does so despite—and, I believe, precisely because—it draws mostly on Australian collections. Centring on forty-five Warhol photographs recently acquired by the AGSA, it features loans from the NGV, the Queensland Art Gallery and the National Gallery of Australia. This survey of works, cannily selected by curator Julie Robinson, manages to provide a representative sample of Warhol’s oeuvre. Its particular photographic focus, however, also opens up a set of less familiar questions about the status of the artist’s work in today’s artistic and technological economies.

The exhibition’s opening gambit is to draw the obvious, but ultimately unconvincing, parallel between Warhol’s art making practice and social media. As you enter the exhibition, the wall reads: “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” In this offhand quip, Warhol the prophet predicts the state of media to come. The director of AGSA attributes the “enduring relevance” of Warhol to this link, asking, “Was Warhol the original influencer?” Warhol’s friend and collaborator Christopher Makos, whose photographs also feature in the exhibition, would agree. In a room further into the exhibition, an interview with Makos rings out on a short loop: “Andy was the original Kim Kardashian.”

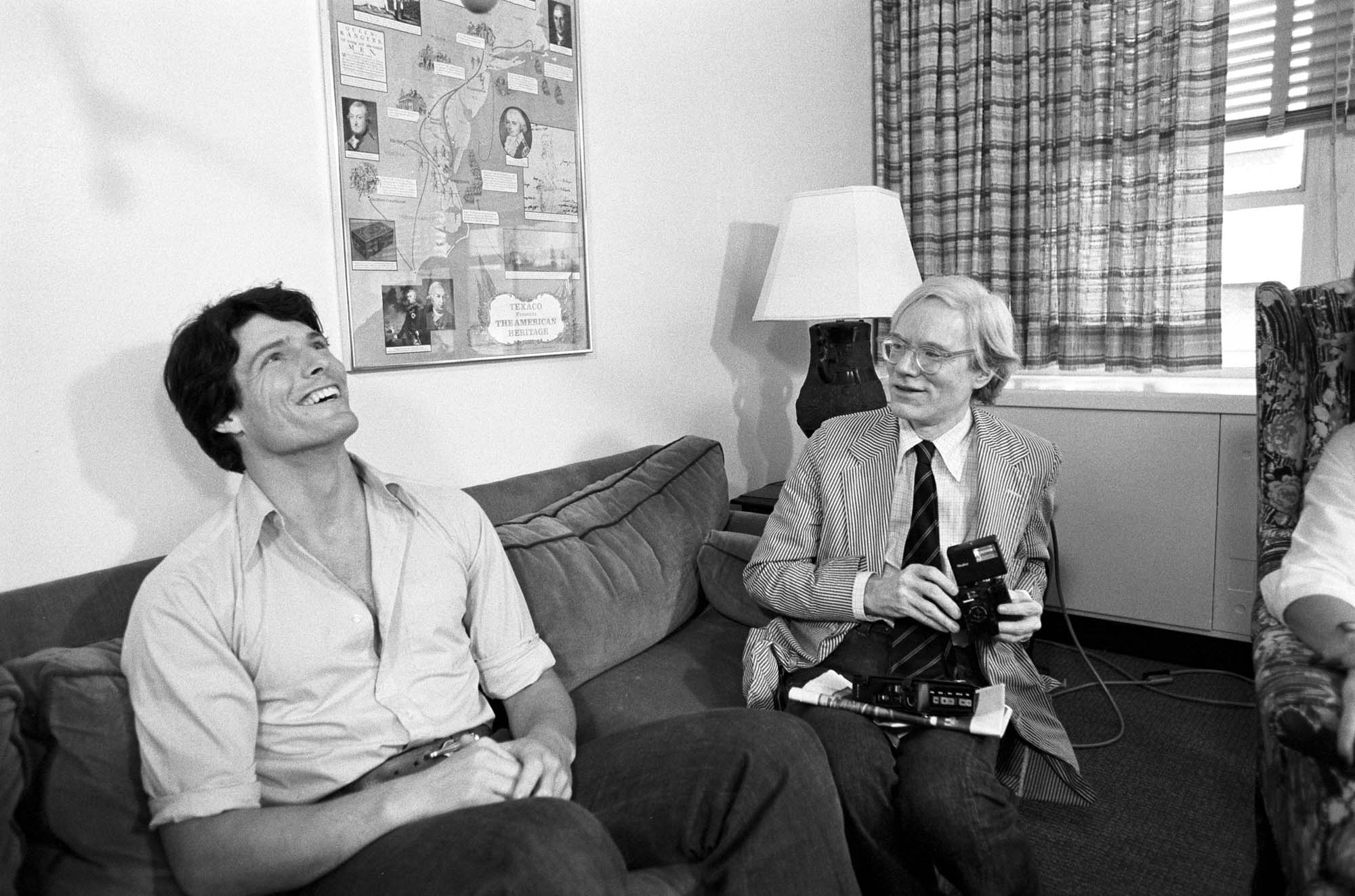

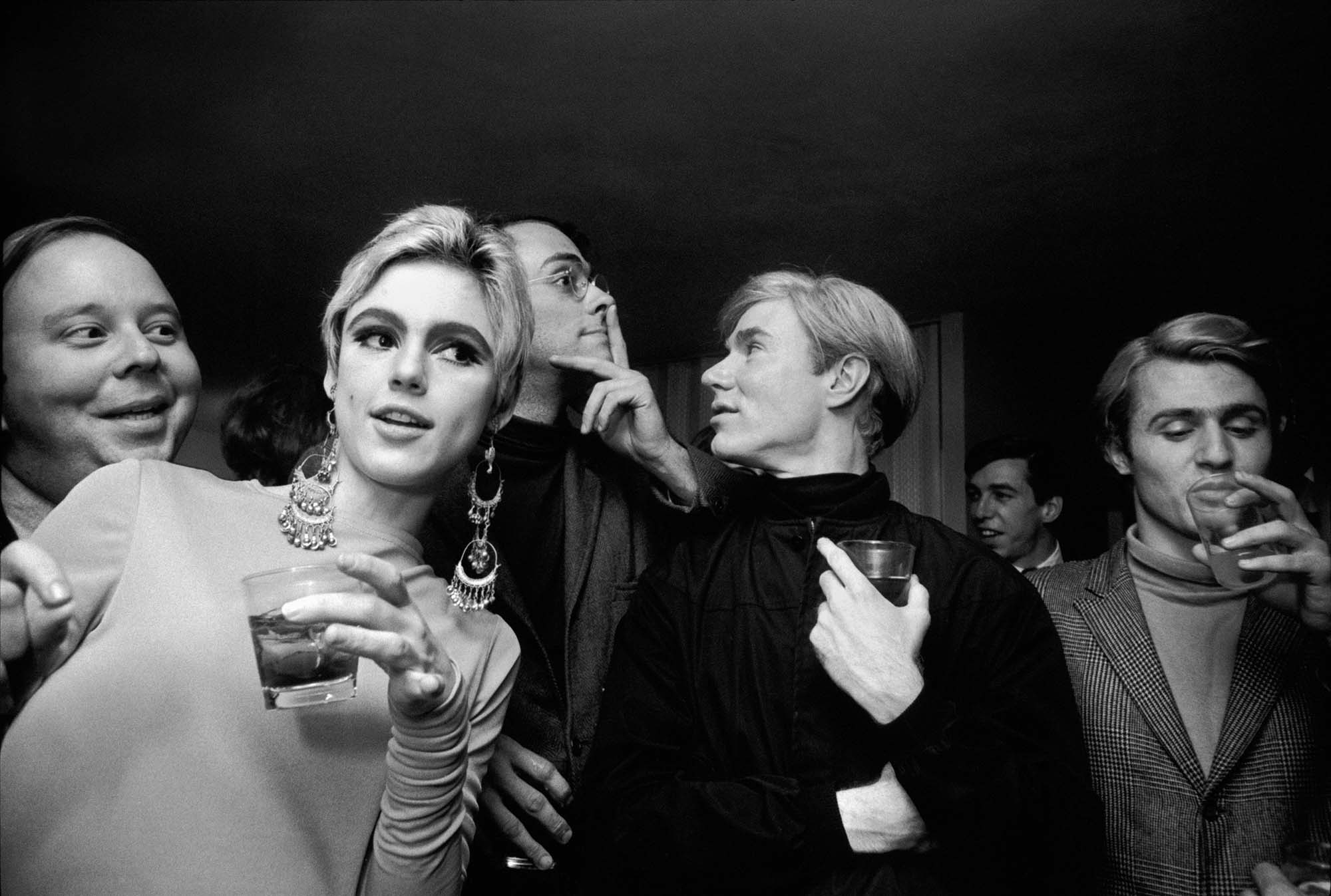

In some ways, Warhol did indeed use photography as “a social media.” Near Self-Portrait No. 9 (1986), footage from a 1986 interview for ITN News at an exhibition opening shows Warhol taking photos of the press while they film and photograph him. This is just one instance of his compulsion to document social interactions. He also recorded most of his conversations with a tape recorder that he and other Factory insiders jokingly referred to as “his wife Sony.” This not only formed part of Warhol’s art practice, which often bordered on performance art in public situations, but alleviated his social anxieties, providing a barrier between himself and others. As Bob Colacello, long-time editor of Warhol’s magazine Interview puts it, the “constant” photographing and taping “gave Andy a role to play” at parties and events.

But one of the reasons that the comparison between Warhol and social media feels insubstantial is because his impulse to chronicle was part of a private practice of collating, rather than a public one of exhibiting. Curator Robinson remarks on how Warhol “took some 60,000 photographs in his lifetime.” However, of this astounding number, few were exhibited. Warhol and Photography includes some exceptions, like Warhol’s late “stitched” photographs—sets of identical images sewn together. It brings to Australia for the first time the only two “editioned” catalogues of Warhol photographs published by gallerist Bruno Bischofberger. There are also images from Warhol’s book of photography, Andy Warhol’s Exposures, and lay-outs of candid shots from his magazine Interview.

Admittedly, Warhol made many aspects of his private life public—we need only consider the lengthy posthumous publication The Andy Warhol Diaries. But without the seal of deliberate public display, Warhol’s photographs have little in common with social media as we understand the term today. Perhaps Warhol’s sixty thousand photographs are something more like the photographer August Sander’s project to photograph six hundred portraits for a series called People of the Twentieth Century on a grander scale. Sander wanted to document every socio-economic and vocational type in Cologne, but his efforts were cut short when his son was arrested for his anti-Nazi sentiment and subsequently died in jail. What remains of his archive is an unlikely social record of everyday people, not dissimilar to the intimate shots in Warhol’s taxonomy of stars and socialites.

There is a sense in which the more eye-catching Warhol works in the exhibition and the curatorial emphasis on Warhol’s relevance to the digital age distracts from what is most unique about AGSA’s collection. One wall of the exhibition presents several of Warhol’s screen tests laid out like an Instagram grid. In this arrangement, the viewer is able to escape the discomfort of lingering on any one of the subjects for too long. It’s easy to miss the moment Ann Buchanan breaks into gentle tears amidst Salvador Dali’s antics with a silver purse and the irritated fidgeting of Bob Dylan. Unlike the more intimate viewing booths showing Haircut (1963) and Camp (1965), we’re encouraged to scan over each frame, avoiding the confronting closeness of the sitter’s stare.

It is the question of reproducibility and authenticity, rather than social media, that makes the AGSA exhibition worth looking at closely. Warhol notoriously reproduced the same works many times, often against the advice of his friends and business partners. When selling a portrait, he would paint a few extra in case the sitter could be convinced to purchase more. He also turned various series of paintings into prints, such as the iconic Campbell’s soup cans. In turn, prints were sometimes traced over to make drawings that formed the foundation for new works. This process of regurgitation and multiplication is partly what made Warhol’s work interesting, and allowed him to redefine the relationship between art and the market. It also had the potential to jeopardise the value of his works. As Warhol fretted in a dispute with film producer Peter Brant, “he can just dump all the paintings he owns in auction and ruin my prices.” The Andy Warhol Authentication Board, established not long after the artist’s death, was dissolved shortly afterwards over costly philosophical disputes about what counted as a Warhol and what didn’t.

This crisis of reproducibility that Warhol’s work elicits replicates the larger crisis precipitated by the invention of photography. As Walter Benjamin most famously argued, photographic works can be duplicated easily and unrestrictedly, which problematises the idea of an “original” or “authentic” version of a work. Photography also made painters reassess their function. It was no longer the purview of the painter to capture something exactly—for instance a realistic portrait—because photography could do this more accurately, cheaply, and speedily. Warhol played with this legacy, incorporating Polaroid photographs into his method for screen printing portraits. However, Warhol remained most interested in the reproducibility of photographs transposed onto artworks, rather than in photographs themselves.

From the perspective of a collector, however, Warholian photography revives the possibility of owning a singular and “authentic” Warhol. Compare the Ladies and Gentlemen (1975)screenprints with the polaroid of Colacello in drag, which are hanging on the same wall in the exhibition. Colacello recalls there being many sets of prints made, and that they were hard to sell. But there’s only one of these particular Polaroids (which Warhol didn’t in fact end up using as inspiration for the series).

It’s true that a Polaroid doesn’t have the same latent potential for reproducibility as a gelatin silver photograph. And it’s not only photographs taken by Warhol, but photographs taken of or in the vicinity of Warhol that are included under the ambit of “Warholian photography”. This means the number of photographs attributed to Warhol might still expand without limit. But as far as things go economically in terms of owning, acquiring, and selling works, the photo can now be had in the sense that an original painting could be, before the double crisis of reproducibility brought about by photography, and accelerated by Pop Art. Consider the facsimile of a photobooth strip of Warhol Self-Portrait (Being Punched) (1963–64), which is framed and displayed next to photographs considered the “real thing”. The former is an example of reproducibility, but without the co-signature of Warhol, it’s moot.

Even if there are multiple photographic prints in a series, these are not allowed to be sold and printed repeatedly. This isn’t the case with the Marilyn Monroe screenprints hanging in the exhibit. After failing to dissolve a partnership with a print shop in Belgium after providing them with his techniques and images, Warhol couldn’t stop them from producing “unauthorised” print sets, which they continue to print and sell today. However unlikely it may seem, in Warhol’s oeuvre, artworks have usurped photographs in their reproducibility.

Reflecting on the exhibition, professor of Art History and Curatorship at the University of Adelaide Catherine Speck laments the “lack of an exhibition catalogue, from a gallery with a reputation for producing prize-winning catalogues.” This does seem remarkable, especially given the cultural tendency to print Warhol images on any number of commodities, from actual Campbell’s Soup Cans to condoms. However accidental on AGSA’s part, this omission points to what is most notable in the exhibition: what is not reproduced or reproducible ad infinitum. The different series of photographs presented are not frequently associated with Warhol in retrospective exhibitions or publications summarising his artistic output. They may be unrecognisable as “Warholian,” even to someone reasonably familiar with his work. What’s more, by virtue of being photographs in a limited series, their potential for reproduction and circulation in the art market is curtailed.

Hanging at AGSA, the single Elvis screenprint has little of the impact we can imagine it had in its initial exhibition at Ferus gallery, flanked by double and triple-figure repetitions on the surrounding walls. Such dissipation of the work’s original aura is unavoidable in any exhibition with retrospective components. In this exhibition, however, a number of other less commanding works stand out. Take the photo Shadow on Sidewalk (1983). The frame is filled entirely by the sidewalk. Cutting across the tilted grid of large pavement stones, a long black shadow—a street sign perhaps?—divides the image in two. In the very top right-hand corner two feet cast a parallel shadow as they walk toward the horizon line out of frame. The composition of the photograph is striking, and reminiscent of the eeriness of Warhol’s abstract series of paintings Shadows (1978–79). This photograph is just one of many curios collected under the banner of Adelaidean Warholianism, which manages to shed new light on Warhol’s oversaturated oeuvre by way of a renewed auratic glow.

Caitlyn Lesiuk is the Convenor of the Melbourne School of Continental Philosophy and a PhD candidate at Deakin University, where she teaches philosophy.