Andrea Grützner: Tanztee and Erbgericht

Kate Warren

Writing in Artforum in 2004, Abigail Solomon-Godeau described the ‘miniature guillotine’ of the camera’s shutter. The camera slices a moment in time from the world, removing it from its original context, but also potentially relaunching it as a new, transformed event. In Andrea Grützner’s current exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, the German artist has focused her photographic attention on a historic guesthouse in Saxony, in the old East Germany. She expertly uses and exploits the click of the shutter to create two series of works that transform the building’s spaces and activities into striking abstract compositions. Yet in doing so, Grützner also reflects and adds to the complex layers of memory, history and ongoing lived experience that permeate this building.

The ‘Erbgericht’ guesthouse, built in the late nineteenth century, has held a longstanding fascination for Grützner. An important cultural centre for the rural community, it also embodies broader historical narratives that persist in contemporary Germany. Cultural theorist Andreas Huyssen influentially wrote about the palimpsestic-like nature of contemporary Berlin (and post-War, post-unification Germany more broadly), which is defined by complex layers of absences and presences, voids and remains. The guesthouse in Saxony reflects such complex relations, particularly its history during the period of the German Democratic Republic. While the guesthouse did not come under direct control of the state, as many buildings did, the GDR did enforce certain aesthetic impositions. This included overpainting certain architectural elements of the building – producing quite literal layers of history, memory and forgetting.

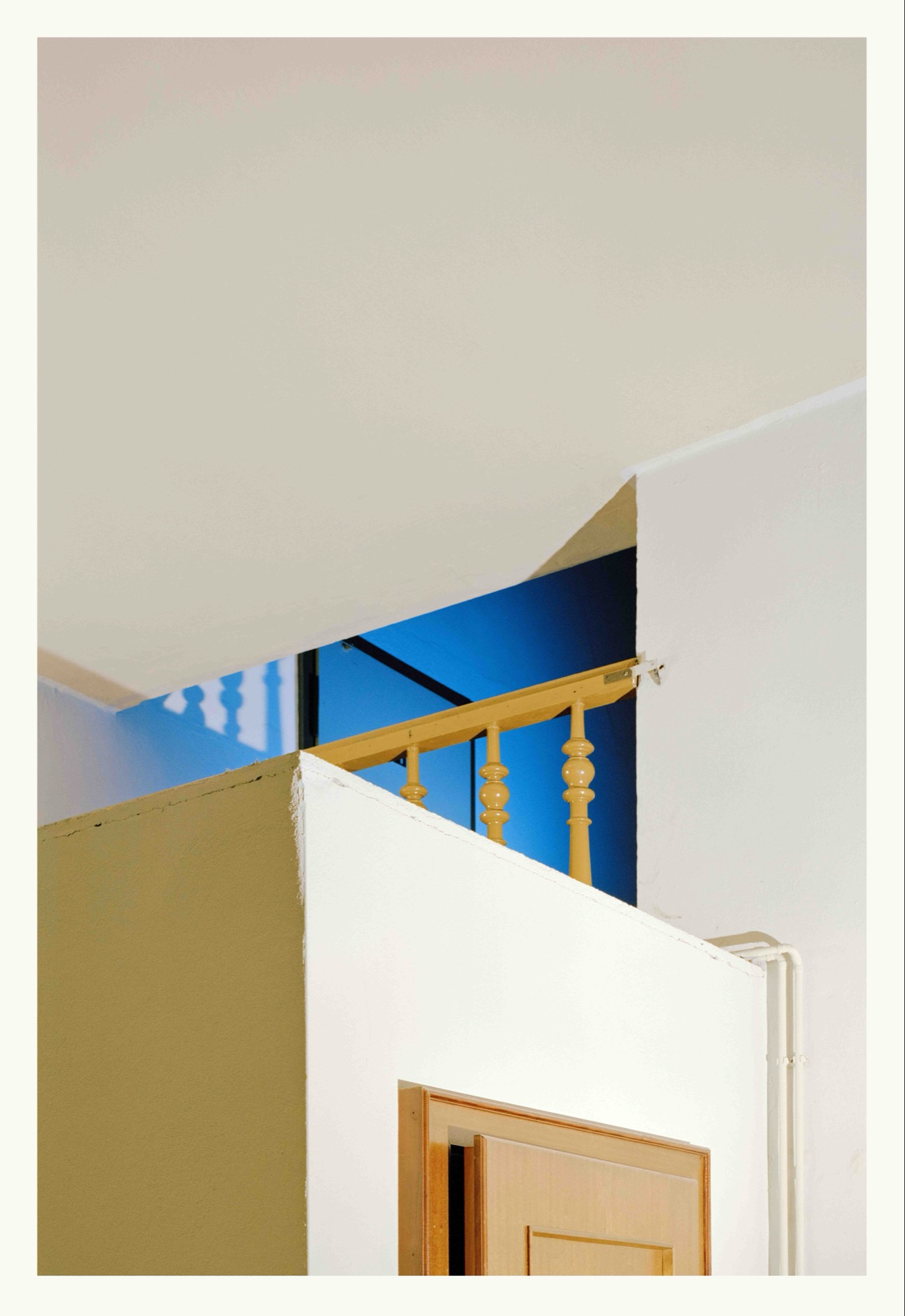

Grützner employs photography’s unique qualities to unsettle and amplify these legacies, exploring the complex connections to space and history that swirl around the guesthouse. For the series Erbgericht she spent a number of years photographing the various rooms and nooks of the house. Yet the photographs on display at CCP are far from simple documentary images. Grützner uses precisely placed lighting and coloured flashes when taking her images. These introduce choreographed washes of colour that flood and saturate certain areas and rooms. All of this is pre-planned and measured. Grützner shoots on analogue film, and with the click of the shutter she both triggers her own ephemeral layers of colour in the space, and captures them in her final images.

Flash-photography can be a harsh tool, and Grützner knowingly uses this to flatten the picture plane. Yet by inserting her splashes of colour, Grützner paradoxically reinserts new levels of depth into her final photographs. Shadows are transformed into fields of colour, layered onto the building’s architecture. While this lends an overall abstract quality to many of the images, her technique is remarkably generative; it produces a suite of photographs that are exceptionally cohesive aesthetically, and yet also very visually distinct and diverse. Some images could pass for pure digital constructions, so crisp and stark are their architectural lines and coloured voids. Other images resemble almost pure abstractions as the cropped viewpoints, indistinct objects and coloured interventions combine to create images resembling collaged (or, more currently, Photoshopped) arrangements. Grützner uses no digital or post-production alterations however; these effects are generated in camera. Her processes create complex, multiple illusions of materiality. In some of the images the slashes of colour are so dense and vivid that they almost appear to have been painted into the frame – alluding subtly to the aforementioned legacy of overpainting.

There is a coolness to Grützner’s works in Erbgericht, but this sits in tension with the subtly expressive elements of the images. These tensions are crystallised in these compelling and complex plays with colour and shadow. While some of the shadows are sharp and hard-edged, in other images the architecture intervenes to create wobbly, undulating silhouettes. In this way, Grützner unexpectedly synthesises diverse legacies of Expressionism. The bold, unexpected and abstract use of colour was one key feature of many European Expressionist painters – from Kokoschka to Kandinsky – with colour becoming a tool for symbolic and inner expression. Yet by linking her coloured interventions directly to the light and shadows generated by the camera, Grützner also references the legacies of German expressionist filmmaking of the 1920s. Long, deep shadows are particularly evocative of these films, such as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920) or Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922). The black and white stocks that these films were shot on accentuated the aesthetic, thematic and psychological plays between ‘the light’ and ‘the dark’. Yet it is often forgotten that colour tints were also used in these films, to heighten particularly emotional or significant scenes. One of Grützner’s images is particularly reminiscent of this legacy. The silhouette of a circular light fitting is projected on a wood-panelled wall, its black shadowiness replaced by a soft pinkish hue that also washes over the adjacent curtains. It could easily be a hand-coloured or hand-tinted image, another intelligent play with photographic materiality.

Grützner’s highly stylised and choreographed images, almost theatrical in their construction and execution, connect to these multiple legacies of Expressionism. Other, more personal expressionistic touches creep in through the accompanying series on display at CCP. While the photographs in Erbgericht are devoid of people, Tanztee reaffirms the ongoing lived experiences of the guesthouse, as Grützner has photographed the Sunday afternoon ‘tea dances’ that it hosts. The dancers, mainly women, wear brightly, almost garishly coloured outfits and Grützner tightly crops her images, focusing on the dancers’ shirts and arms as the grip their partners. Arranging these tightly framed photographs in a horizontal grid, Tanztee is a bold splash of disorderly colour that, despite its frozen motion, manages to capture the rhythms and rapid movements of the dance.

This tight framing also reaffirms how Grützner’s overarching approach is not characterised by particularly nostalgic or melancholic sensibilities. Likewise in Erbgericht her coloured interventions invite her viewers to approach the spaces with playfulness, intrigue and imagination – much like the dancers’ ongoing use of this layered building. Grützner’s photographs combine visual abstraction with lived experiences and historical traces. Her camera cannot, nor does it try to hide the cracks and blemishes that inevitably disrupt the visual planes of her images. Some of the most compelling photographs in Erbgericht are the ones where the precisely measured blocks of shadow-colours are butted up against the physical wear-and-tear of the guesthouse. In one image, a chipped black piano stands in the foreground of a canary yellow door opening, while underneath it the peeling white paint of a staircase is overlaid with candy-cane red stripes. These are the physical traces of time past that cannot be concealed, but they are also the evidence of this building’s ongoing, dynamic relations to its histories and its community. Through her own miniature guillotine, Grützner both preserves and transforms these relations, launching them into new aesthetic and social orbits.

My thanks to Professor Melissa Miles for providing some vital feedback on this text.

Kate is a writer, curator and researcher based in Melbourne, with a particular interest in cross-overs between contemporary art, film, photography and moving image practices. She received her PhD in Art History from Monash University in 2016.

Title image: Andrea Grützner, Untitled 5, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Julie Saul Gallery, New York; Robert Morat Gallery, Berlin.)