Agent Bodies

Tara Heffernan

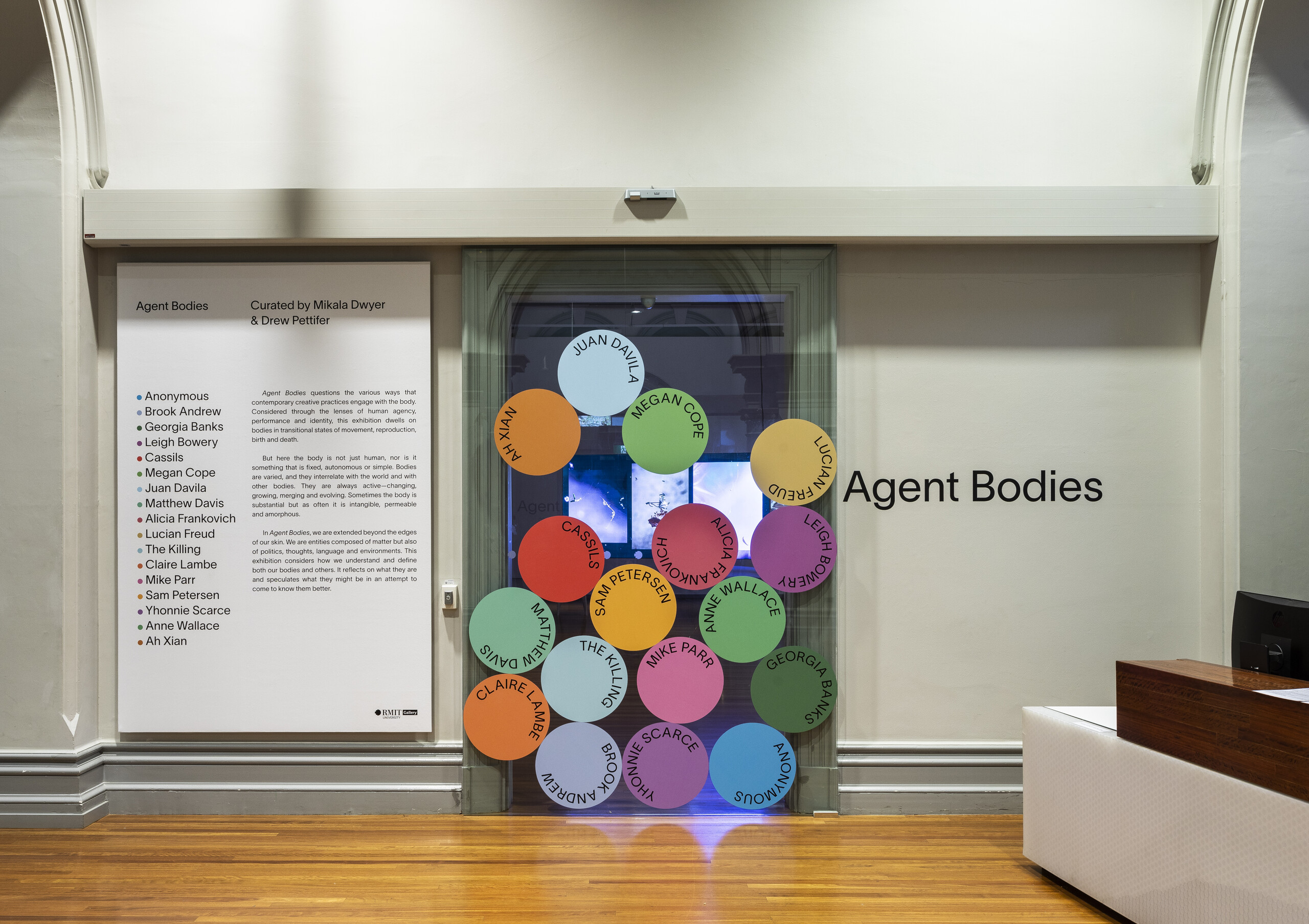

Curated by Mikala Dwyer and Drew Pettifer, Agent Bodies at RMIT Gallery seeks “to enable a better understanding of what a body is”. We “live inside our bodies every day”, the catalogue says, but “how often do we stop to consider how entwined they are with our identity and our world?” Considering the breadth of the practices represented, the answer it seems is very often. However, something far more subtle and pertinent emerges in the meeting of works in Agent Bodies—a revelation of the ambivalence of discourse regarding illness and otherness and its symbolic life.

Scattered around the exhibition spaces are large plush toys by artist collective The Killing. With their malformed limbs, elongated appendages and exaggerated expressions, the plushies are cutsey but chaotic. They resemble 3D realisations of the menacing humanoid figures of Jean Dubuffet or cartoon characters from Adventure Time (2010). On my visit, a giant plushie resembling a humanoid bull, donning a torn checked apron, is lying supine on the gallery floor. The plushie resembles a child, with its stubby limbs, large head and cartoon eyes. A lone wooden chair sits by its side. To my mind, these cues conjure ominous associations with the childhood bedroom and abuse. The chair is, however, part of a separate artwork by Sam Petersen. As an artist who uses a wheelchair, Petersen is interested in the everyday spaces we occupy and the way we share them. In Just Sit (2022) Petersen invites gallery visitors to sit on a chair fitted with a plasticine seat. Sitters leave their individual butt print, contributing to a changing form as a collaborative act of sitting and shaping.

Like Petersen, The Killing encourage gallery visitors to move their work around the gallery: a relational art gesture that carries the association of play. But the plush toy and the suggestion of parental care, and its link with authority and control, carries other associations in the journey to adulthood. Think of the heterosexual trope of the too-big teddy bear won in the carnival game—a gift from a teenaged boy to his girlfriend exchanged for the unspoken promise of sexual compensation. As emphasised by the incidental juxtaposition of the chair and toddler plushie, these toys might reflect the potential tyranny of generosity echoed in the adult world of charity and philanthropy: structures that paper over inequality and control with the pretence of benevolence.

Almost parallel, adjacent to the entryway to the main gallery space, are two sombre works by Yhonnie Scarce and Brook Andrew confront colonial violence and the objectification of Indigenous bodies in the name of medicine and science. Scarce’s In the dead house (2020) displays flayed bush bananas made of glass atop vintage mortuary tables. The work references the Dead House, a stone mortuary located in Adelaide that was frequented by physician William Ramsey Smith, known as a prolific collector of Aboriginal remains. Though you’ll miss this without consulting the wall text, it’s easy to recognise the mortuary tables for what they are. With the suggestion of post-mortem practices, the delicate glass forms begin to resemble burst wombs or perforated skulls. Andrew similarly confronts the history of anthropology and phrenology in The Language of Skulls (2018), a screen print merging archival ethnographic material with pop iconography.

Within the main gallery space, a video work by Megan Cope occupies a large portion of the back wall. In THE BLAKTISM (2014), Cope is the centre of a ritual dubbed “blaktism”, a mock baptism to affirm her Indigenous identity conducted by a priest. The work was made in response to the legal process of obtaining a “Certificate of Aboriginality”. In this ritual, Cope inserts contact lenses in to hide her blue eyes and has her skin darkened with pigment to appear more “authentically” blak. It is a tongue-in-cheek comment on authenticity and stereotyping in Australian culture. Confirming your identity and status in a community through bureaucratic processes might indeed be bothersome and destabilising. However, the flip side is that people do cynically claim the status of disadvantaged groups for government benefits or job opportunities. Though Rachel Dolezal is perhaps the most famous example, in 2020 it was revealed that Jessica Krug, a white American historian of African American studies, had posed as black for the duration of her academic career. Graduate student CV Vitolo-Haddad was exposed for the same transgression.

THE BLAKTISM features a host of Australian stereotypes including a beach babe, a tradie and a raver, among others. As in many art videos, these characters are not portrayed by actors or “real people” but by the artist’s friends. While they cosplay as, or embody to some degree, Aussie stereotypes, they are united by their belonging to the creative class, an identity category significant in forging opinions and ideological beliefs, despite disparities in economic wealth or socio-cultural background. Interestingly, the priest—the most senior of the cast—is played by Kevin Wilson, a Brisbane-based curator. If we consider this background, THE BLAKTISM might serve as an inadvertent allegory for the identarian politics of the creative class where curators seek out and emphasis difference as a high form cultural tourism and catharsis.

Body paint and rites of passage appear in another work in Agent Bodies. A grainy video documenting a performance by Melbourne-born drag icon Leigh Bowery plays on a TV in one corner of the main gallery space. Filmed at drag festival Wigstock in 1993, Bowery sings The Beatles ‘All You Need Is Love’ (1967), ending the song by leaning back and birthing his wife, who has been concealed in a fat-suit clinging to his torso. She bursts forth, head-first, naked and slick with paint from between his splayed, kicking legs as he repeatedly wails “she loves you, yeah yeah yeah”. As Susan Best highlights in the exhibition catalogue, the video is still striking three decades later. Indeed, today it’s difficult to remember that drag is more than exaggerated makeup, quaffed wigs and cattiness. It can also foster genuinely interesting, bawdy and absurd performance work. A cursory viewing of a “best of” compilation of RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009-) reveals pointed conservativism and stifling homogeneity: ecstatic screeching over exposed buttocks or other trivial spectacles, a medley of celebrity guest judges and elaborate makeup paired with ornate gowns indistinguishable from MET gala media-bait ensembles of the past decade.

Over two decades later, LA-based artist Cassils has continued to embrace body shock in endurance pieces that don’t entirely eschew theatricality and humour. Projected on the wall of a smaller gallery space, Agent Bodies features two video works played in succession by Cassils: Monumental Push (2017) and Hard Times (2011–2013). The former documents an event occurring in Nebraska, 2017, in which members of the LGBTQI+ community pushed an 860kg bronze sculpture—a cast of a mottled pile of clay produced by Cassils in an earlier endurance performance—to significant sites for the queer community: places of trauma, celebration and togetherness.

Influenced by body building culture and its campy aesthetics, Hard Times is a contemporary reimagining of the myth of Tiresias. The short film depicts Cassils performing a slow-motion exercise routine in a shiny bikini, frosted wig and horror show theatrical makeup that resembles a barbie face with burned out eye sockets. Their body trembles as the routine becomes fatiguing. The idealisation of the body and its limits is theatricalised. Ecstatic cheers celebrate a seemingly perfect, toned transmasculine body in a shiny bathing suit, chiselled contours exaggerated by probing spotlights. With its tongue-in-cheek nod to horror, the film also recalls the Rocky reveal scene in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) when Dr. Frank N. Furter unveils his creation, the oiled up, muscular blonde monster portrayed by model Peter Hinwood. Although RHPS is celebrated for its representation of gender diverse characters and remains a landmark in queer cinema, the moral tale still punishes excess. A campy take on B-movies and sci-fi cliches released during the final peak years of the sexual revolution, the plot is loosely lifted from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). Shelley’s fable warns of the failing and expendability of the human body in the face of progress as embodied by Dr. Frankenstein’s immortal, murderous creation. RHPS updates this to the emergent age of image production and hypersexualisation. Despite the hedonistic promises of the sexual freedom, there are still boundaries. Desire is messy and bodies are fallible. None of us are machines or monsters, but we can become images.

Cassils’ performance practice is comprised of many similar endurance pieces that test the limits of the body. In an Australian context, Mike Parr has similarly dedicated his career to confrontational body art. Screened in a room adjacent to Cassils’s work is La Triviata/Bad Son (2010-2013). The footage depicts Parr grimacing as a thread is sewn through his flesh. His aging body suffers in slow agony. Like Bowery’s documentation, it looks raw and shaky—a contingent feature of the live event—not carefully crafted with aesthetic sharpness and clarity like Cassils toned body. For Cassils, like the physical body, documentation is a perfectible medium, even if the body reveals its struggle. There’s a to-be-looked-at-ness shaping the body and the image. Very contemporary.

For an exhibition about bodies and the experience of having them, the logo and design used to promote Agent Bodies is strikingly rigid and inorganic. It comprises a series of perfectly uniform dots, distinguished by subdued colours and the names of the artists/collectives in bold, utilitarian text. There’s a corporate sterility to it: it resembles a simple computer-generated power-point title slide. This struck me as significant …

In a recent essay, Theodor Kerr has suggested that polka dots are a subtle symbol of the HIV/AIDs crisis. Echoing their presence in contact tracing maps published in medical journals in the early days of the virus, each circular cell represents a patient. Kerr identifies the polka dot motif in artworks and cultural moments, including the fabric swaddling the recently deceased in AA Bronson’s photograph Felix Partz June 5 1994 (1994), the tiles in Leslie Kaliades’s Self Portrait (1989) and the costumes worn by Madonna’s HIV positive back up dancers in the 1980s. Bowery also gets a mention. The decorative, balaclava-like face coverings worn by Bowery—which were synonymous with his image—often featured dot-like motifs, rumoured to aestheticise the facial lesions suffered in the later-stages of AIDS infection. Indeed, illness and mortality haunt the exhibition.

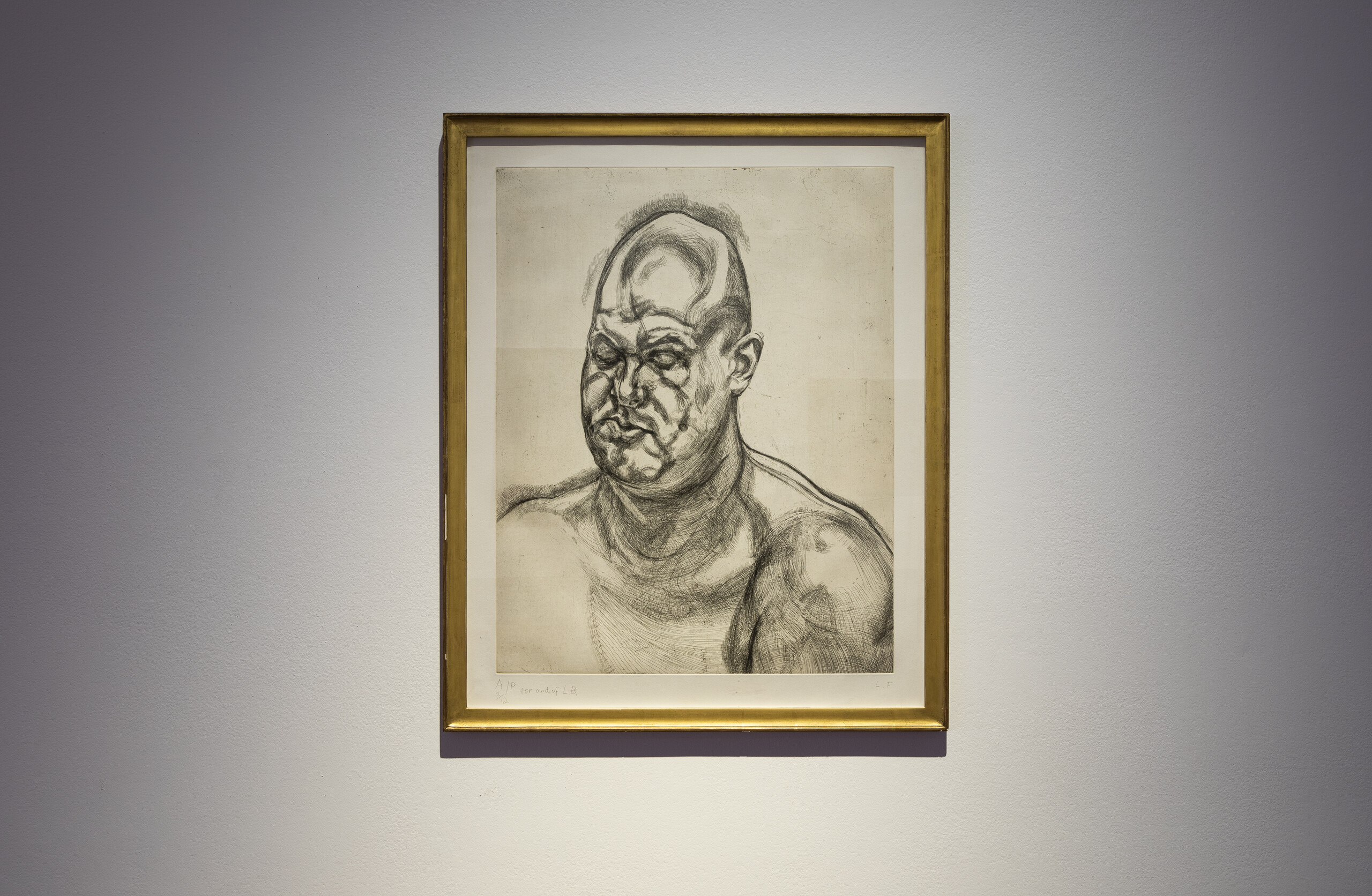

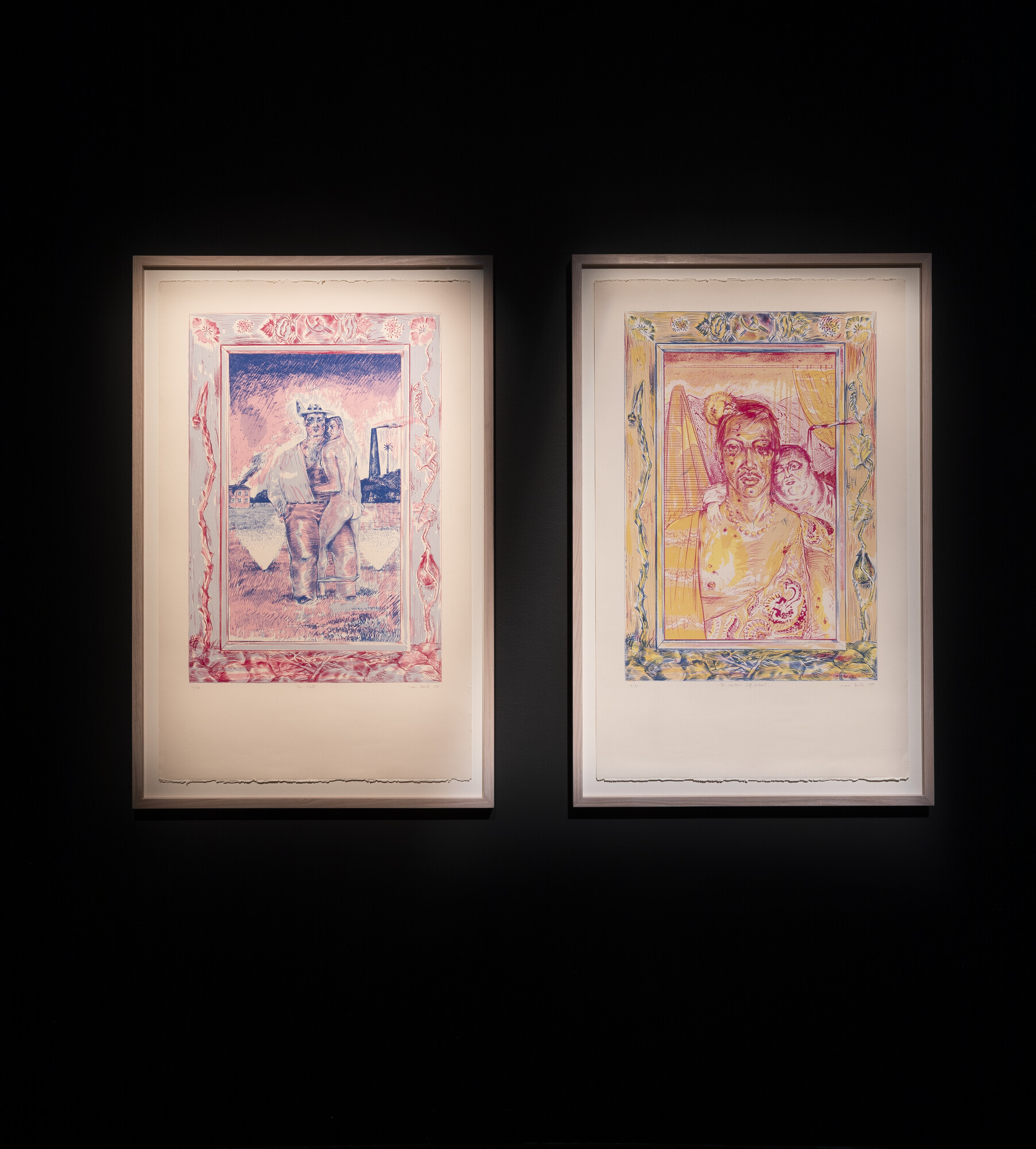

Bowery died of AIDS a mere year after his Wigstock performance was filmed. Filling the floorspace by Bowery’s video work are large display cases containing Bowery’s costumes and props including corsets, merkins and a bra. It’s strange to see this archival material used to sum up a person. It echoes another work in Agent Bodies produced by an anonymous artist. The work, entitled J. Doe (2022), is a collation of evidence (including a mock crime scene investigation video) and forensic samples (nails, clothing and personal effects) taken from the anonymous artist’s body. The work raises similar questions about bodily traces and their symbolic significance. Does it matter, or is it just stuff? In another, more traditional form of documentation and symbolic preservation, a framed etching by Lucian Freud, Portrait of Leigh Bowery (ca. 1992), hangs on the wall to the left of the Wigstock video. Freud’s etching maps the ripples of flabby, excessive flesh on Bowery’s face and its expressive potential. He’s naked, but he’s all there. This portrait seems more compelling than deflated garments and fake pubes. Two lithographs by Juan Davila, The Field (1988) and Pre-Modern Self Portrait (1988), further testify to the power of portraiture. Creating during the height of the HIV/AIDS crisis, Davila weaves art historical and political reference points together in these poignant self-portraits which acknowledge the nexus of symbolism and corporeality in illness’s metaphorical potency.

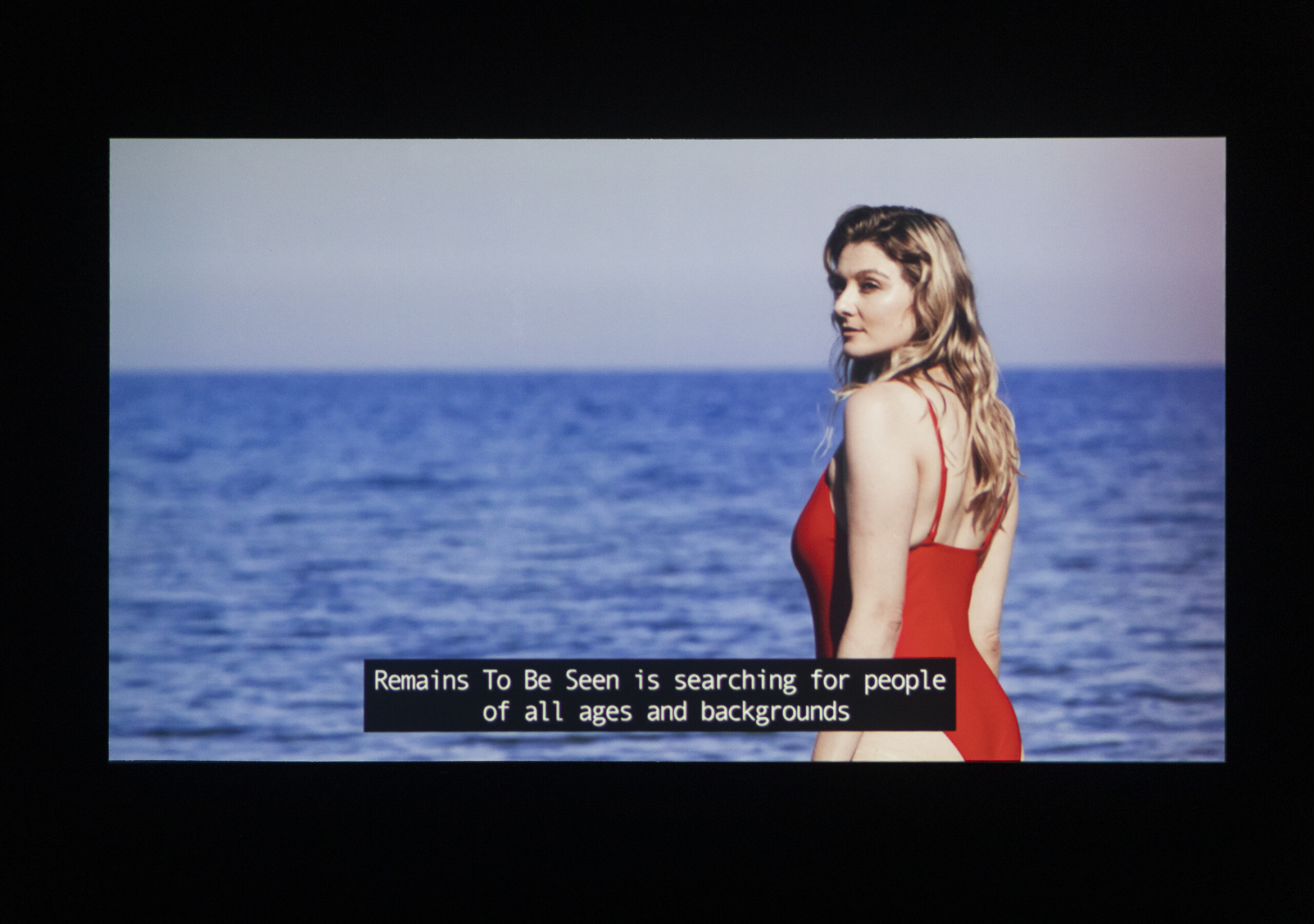

Further obsession with the body’s physical leavings manifests in Georgia Banks mock reality TV show, Remains to be Seen. Taking cues from The Bachelorette (2003–) and Married at First Sight (2015–). Remains to be Seen isn’t about the search for a romantic partner. “I’m not looking for my happily ever after”, Bank’s explains in the squeaky affectation of an underripe Australian soap opera starlet. “I’m looking for my happily ever after life”. She seeks a lucky winner to manage her funeral arrangements. Though Bank’s does hint at producers’ appetite for humiliation and cultivated cruelty, I suspect that, like Donald Trump, reality TV is beyond parody. It flaunts its exploitative nature and revels in the cruelty and antagonism of its participants. This is precisely the point. As iconic director and connoisseur of bad taste, John Waters, highlights, much of the pleasure taken from viewing reality TV is directly related to this antagonism. One of the first reality TV programs took its name from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), after all. Big Brother is watching, as are we.

Death isn’t unique in the history of media spectacles: Wallace Souza, a Brazilian politician and host of the series Canal Livre (2007–2009) allegedly hired hitmen to create more crime content. In the early 1990s, former darling of the Austrian liberal elite, Jack Unterweger, interviewed the friends of sex workers he had himself murdered. If anything, Banks’s proposal is more ethical than real reality TV. Though death seems spooky and sensational, somebody you meet via a game show will likely do less harm to you dead than alive.

Returning to the question proposed at the beginning of the review: How intertwined is the body with our identity? Agent Bodies seems testament to the contemporary overemphasis on their interaction. Accompanied by the declining emphasis on structural politics, self-care (and other thoroughly normalised wellness practices focused on the individual) emerged in the past few decades as a method of maintaining both the symbolic body and the physical body, in tension due to the demands of contemporary life. Inevitably, this has inspired the misconception that they are one and the same. It’s crucial to acknowledge that the timeframe represented in Agent Bodies captures a period bracketed by the later years of the HIV/AIDS crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Discourse concerning health, identity and sexuality, and the ideological framing of body politics, has been incontrovertibly shaped by this culmination of events.

In a provocative article published in December 2021, Blake Smith ponders ‘Are conservatives the new queers?’ His argument stems from the moralism of the Covid-19 pandemic, in which the left thoroughly embraced biopolitical control and happily propagated the punishing dramaturgy of illness. As Smith argues, today we might contend that conservatives are the heirs to Foucault, flouting state-mandated health protocols and the cult of wellness:

Calling for churches and synagogues to stay open last year, they insisted on the importance of chosen ties, even biologically risky ones, against scientific protocols that imagined the good life only in terms of bodily health.

Politics aside, what is fascinating here is the framing of the body as a contingent feature of life that transcends corporeal experience—a belief system that might be decried as religious but, as Smith points out, isn’t that removed from the experience of gay communities that persevered through the 1980s.

Almost concurrent with the Covid-19 pandemic, queerness has become an ideal neoliberal category, embraced by the market and by liberal cultural institutions eager to wring out the last beads of subversive clout while signalling their alignment with progressive politics. In this turn, the Pride Flag has become virtually synonymous with corporate aesthetics. “It seems to say”, Nina Power has reflected, “there is no nature left, no natural rainbows”. No nature and little deviation from market and state-sanctioned belief systems. Counter to these homogenising gestures, Agent Bodies appears to offer a subtle nod to the covert influence of illness and otherness in the coding and cultural articulations of corporeal experience. The latent and perhaps inadvertent queer associations of the polka-dot motif reflect this undercurrent. But while it eschews the overt didacticism of the culture wars, the impetus guiding Agent Bodies does seem to follow the dubious and very contemporary microfoundationalist view that society is reducible to individuals and individuals are defined by their bodily experience. If we can only see ourselves as bodies, then our sense of self relies on our vitality, our autonomy and our corporeal relation to the world around us. We are our bodies, but we’re also more than that—we are our communities, our commitments and our acts beyond the physical, corporeal mess of life. I look forward to seeing more art that reflects this.

Tara Heffernan is a blind art historian currently completing a PhD (Art History) at the University of Melbourne on the work of post war Italian artist Piero Manzoni. Her academic work focuses on global modernism and the avant-gardes with an interest in their ongoing aesthetic and political relevance to contemporary debate