A Biography of Daphne

Paris Lettau

“Wherever the might of Rome extends in the lands she has conquered, the people shall read and recite my words”. So says Ovid in the penultimate sentence of his Metamorphoses, the first-century, fifteen-book epic poem that gives Ovid’s Roman account of the creation of the universe and the history of the world up to the coronation of Julius Caesar. Today, Rome has conquered the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in A Biography of Daphne, an exhibition by Romanian curator Mihnea Mircan. The exhibition takes the eighth story of Ovid’s poem, Daphne, which tells of the young god Apollo’s forceful pursuit of his first love Daphne, daughter of the river Peneus, to provide a complex, open, and deeply ambivalent investigation of trauma and transformation in contemporary art.

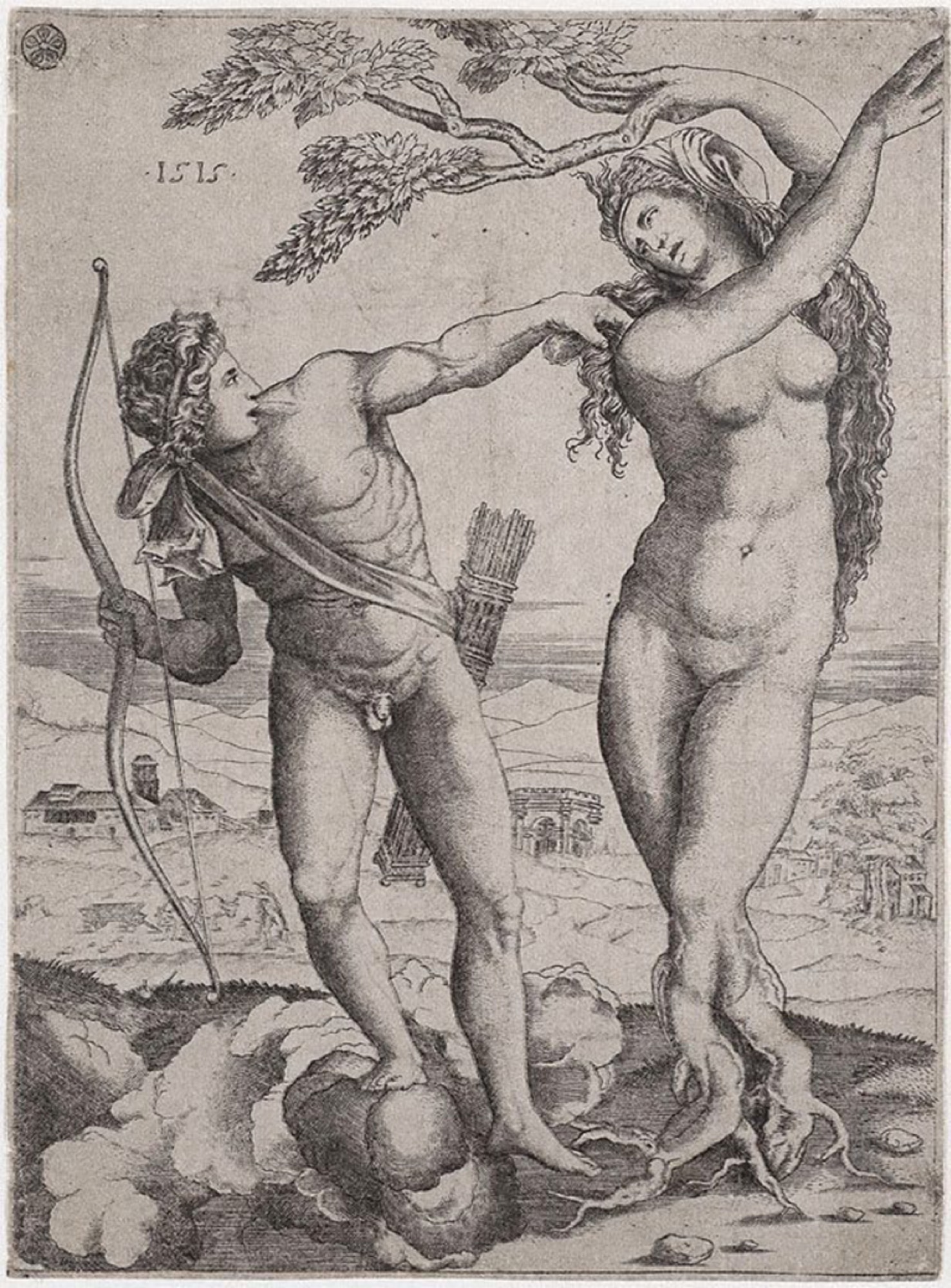

In Ovid’s story, blind chance is not blamed for Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne—nor Daphne’s flight from Apollo—but Eros’s resentment. Flush from his first military victory over a monstrous serpent, Apollo spots Cupid drawing his bow and arrow and teases the little cherub for playing with adult weapons. Spiteful, Cupid shoots Apollo with an arrow that rouses in him uncontrollable passion, and into Daphne he implants an arrow that repels it. Wounded by Eros, Apollo catches sight of Daphne and falls instantly in love and longs to have her. Daphne wishes to remain a virgin, and when Apollo dotes over her, she flees. Pictured as a menacing greyhound, Apollo takes frenzied pursuit until, catching up to her, and with his breath on her neck, Daphne pleads with her father Peneus to disfigure the beauty Apollo lusts after. With that, Daphne metamorphoses into the world’s first laurel tree.

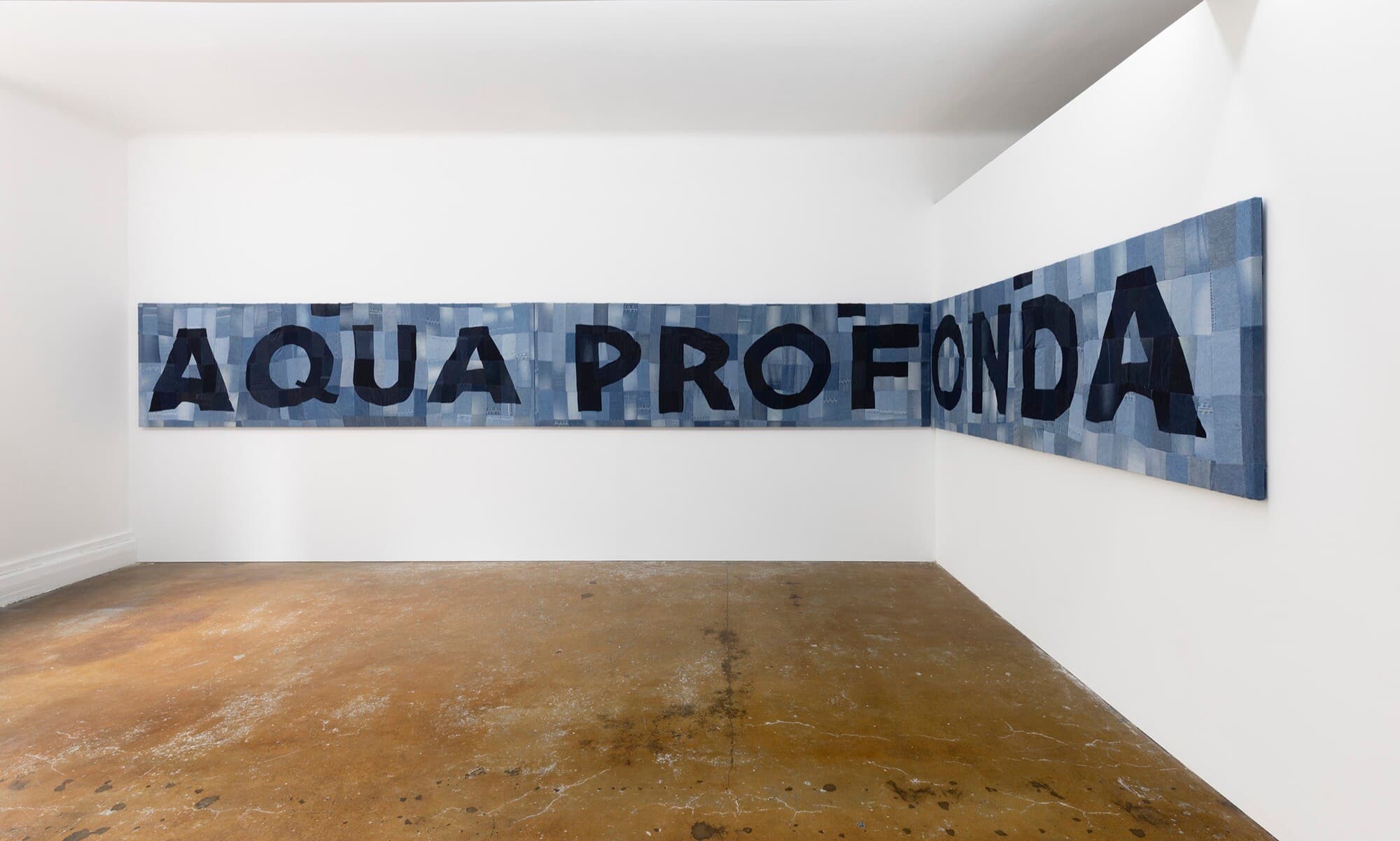

Mircan takes this interval between the chase and the moment of capture as the central motif for A Biography of Daphne, bookending the exhibition with two works hanging exactly behind one another on either side of the northern wall, which separates the first and the last room of ACCA’s galleries. The first, Anthonie Waterloo’s intriguing little etching Apollo and Daphne (1650s), opens the exhibition with the scene of Daphne in mid-flight from Apollo; the last, Agostino de Musi’s (a humorously poor draughtsman) engraving Apollo and Daphne (1515) shows the moment of capture and the beginnings of Daphne’s metamorphoses.

The exhibition spaces at ACCA initially mimic the dactylic poetic metre of Ovid’s Metamorphoses: one long room followed by two short ones. The first long foot presents about a dozen works that pivot around a central sculpture, Fixed Fountain (2021) by Jean-Luc Moulène, itself pivoting and doubled on the axis of the figure’s centre of gravity, suggesting a transition from an upright portrait format to a sideways landscape one. This shift along the axis of two European pictorial genres is cast by Mircan as yet another motif of transformation. It is suggested as well in Becky Beasley’s P.A.N.O.R.A.M.A. (2010), postcards depicting segments of Eadweard Muybridge’s fenced Victorian garden, taking the portrait format of the postcard and turning it into an unending panorama of pictures spinning on a carousel.

To learn what this exhibition is about, however, one does well to simply canvas a conversation with Mircan and attend to the words appearing in his everyday vocabulary: catastrophe, danger, nightmare, disaster, crisis, trauma, rupture. If Mircan casts Daphne as an allegorical figure through which we can consider questions concerning climate emergency (e.g., Nicholas Mangan, Erik Bünger) or the relationship between human life and plant life (e.g., Jean-Luc Moulène, Erik Bünger, Mathew Jones) he also foregrounds the explicit patriarchal sexual violence of Ovid’s Daphne story in several works, including Gabrielle Goliath’s Elegy (2015), an ongoing performance where each piece is presented with a eulogy to victims of gendered violence.

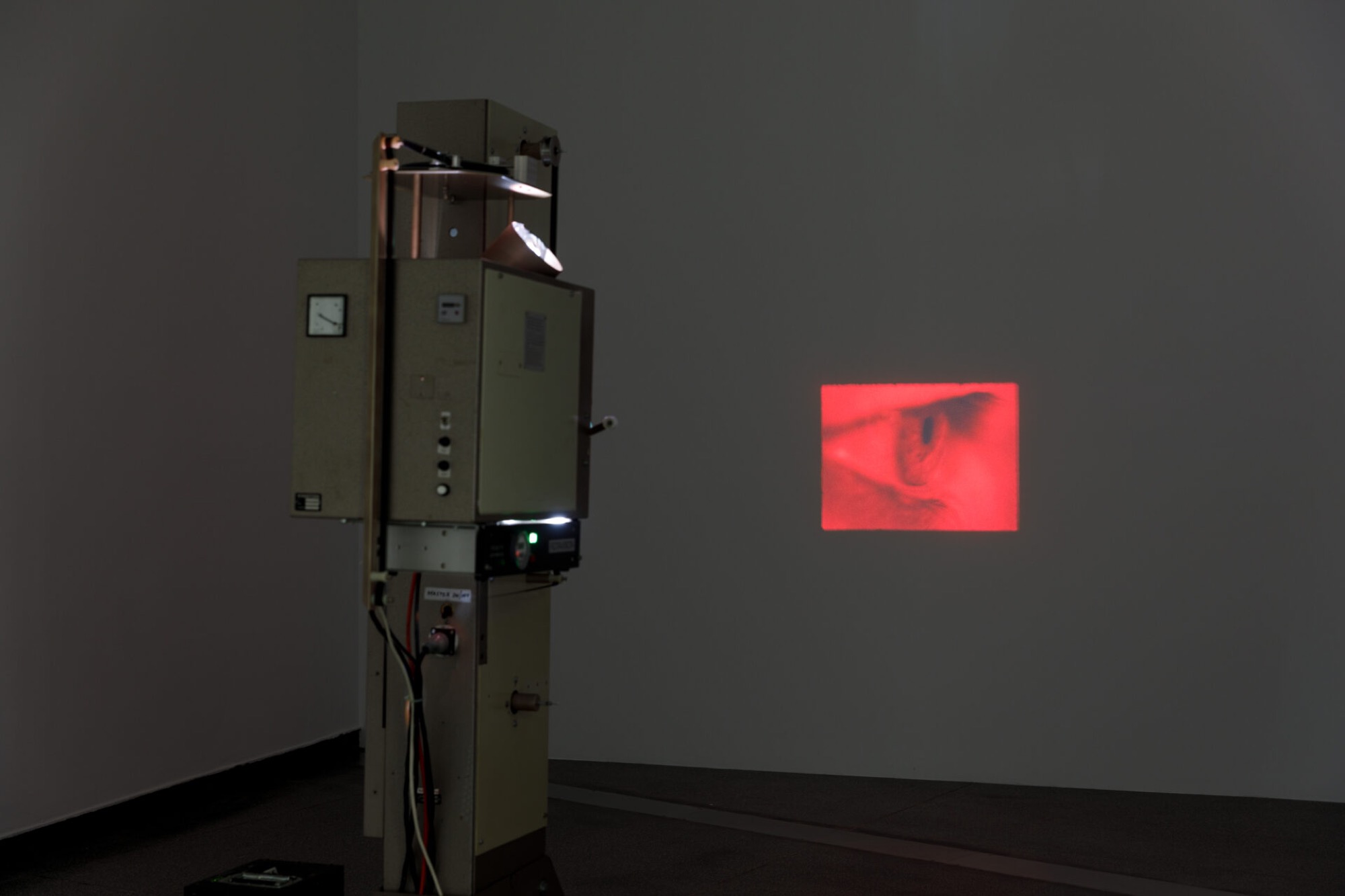

Other works deal with the violence of transformation and the transformation of violence. Lauren Burrow’s A stick developing eyes (2021) presents the incredible story of the philosopher Val Routley who underwent a personal and intellectual metanoia after being death-rolled by a crocodile at Kakadu in the 1980s. Burrow captures that moment when the beholder is beheld in a petri-dish of bright crocodile eyes, which burn and twinkle like stars.

Ciprian Mureșan attends to the iconography of Daphne to address questions concerning the reproduction and reception of icons of western art history in Drawing after ‘Apollo and Daphne’ by Bernini photographed from different angles (2021) and Drawing after a selection of representations of Daphne from the archive of the Warburg Institute (2021). The works make use of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne project by remixing and redoubling a palimpsest of reproductions. Like Warburg, Mureșan, who grew up in post-communist Romania, is as much concerned with the image as with its civilisational support.

Warburg was captivated by antiquity’s survival in images inscribed into cultural memory as forms giving shape to timeless human affects. Daphne is in this sense an icon of Rome’s survival in the civilisations “conquered” by its European progeny. Remarkably, A Biography of Daphne presents works from twenty-one mostly European artists hailing from places like Paris, Amsterdam, Cluj, London, Geneva, Bucharest and Zagreb, with just five Australian artists featured. The same Eurocentrism is glimpsed when some of the central protagonists of the exhibition show their faces: Aby Warburg, Alan Turing, Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (i.e., Ovid), the Surrealists, Charlotte Rampling, the Stedelijk Museum, Piet Mondrian, Rosa Luxemburg. The list goes on.

The European experience of historical violence and trauma also takes centre stage in the exhibition, in which one feels most acutely, both directly and indirectly, the traumas of World War I and II and their many aftermaths. And Mircan likewise captures a European fascination with dualities like history and prehistory, landscape and portraiture, being and becoming, figure and ground, nature and culture.

Are we, then, to make the provincialist accusation of Eurocentrism? Surely not. In fact, surprisingly, at the exhibition opening’s Welcome to Country, N’arweet Carolyn Briggs congratulated ACCA and the curator for successfully staging an exhibition with so few Australian artists. Sentiments like this would be unheard of during the Eurocentric-reign of ACCA’s previous director, just five years ago. Since then, ACCA has reterritorialised with a focus on the local, and especially Victorian First Nations artists.

The exhibition’s seeming Eurocentrism strikes a particular note when one considers that five years ago Mircan curated Allegory of the Cave Painting at the Extra City Kunsthal, Belgium, which took its premise from the ice-age Gwion Gwion rock paintings from north-western Australia. Not resting on his laurels, Mircan shows a belief in the equalising power of mythology, as if connecting us to that original muck where all exists in conflict inside one primordial body called chaos.

Rather than Moulène’s Fixed Fountain (2021), the true pivot of ACCA’s main gallery is the brightly painted Kawun (2005) by Wingu Tingima. Remarkably, the Seven Sisters dreaming, which Tingima was a senior custodian of, tells also of eros’s lechery and treachery, this time through the figure of Nyiru who, wanting to snatch one of the fleeing sisters, tries to trick them by transforming himself into a quandong tree.

Unlikely correspondences continue in A Biography of Daphne. Consider the following from Ovid’s second story in Metamorphoses, ‘The Four Ages’, which tells a version of humanity’s fall from a golden age of harmony with nature to one of the exploitation and expropriation of the earth:

The Land which had been as common to all as the air or the sunlight was now marked out with boundary lines of the wary surveyor. The affluent earth was not only pressed for the crops and the food that it owed; men also found their way to its very bowels, and the wealth which the god had hidden away in the home of the ghosts by the Styx was mined and dug out, as a further incitement to wickedness.

Now consider West, a Yindjibarndi woman from Western Australia, who offers the following reflections on her series warna (ground) (2018) of hand-dyed textile works hanging on the back wall in A Biography of Daphne:

I have been thinking about how the one metre square unit of measurement shapes our relationship with the Earth. How this concept feeds notions that the Earth is rendered blank and called property to be divided up owned and consumed.

In A Biography of Daphne, Mircan wishes to constrain us to a state of flight. His point is not to supply us with a platform on which we can take a position, assess, comment on and judge. That is the job of post-myth academia. Instead, he enters us into the flow of time and history, with all its violence, ambivalence, and indistinction. This being “in the flow” is metamorphosis, or rather it is myth itself. That’s where Mircan leaves us and where he wants us to remain. We are the flowing river gods Ovid writes of in Io, the story immediately following Daphne. They bear witness to Daphne’s traumatic transformation. Yet reputedly, perplexingly, the rivers came together at a gathering place after the incident uncertain whether they ought to congratulate Daphne’s father or offer condolences.

Paris Lettau is a contributing editor of Memo Review.