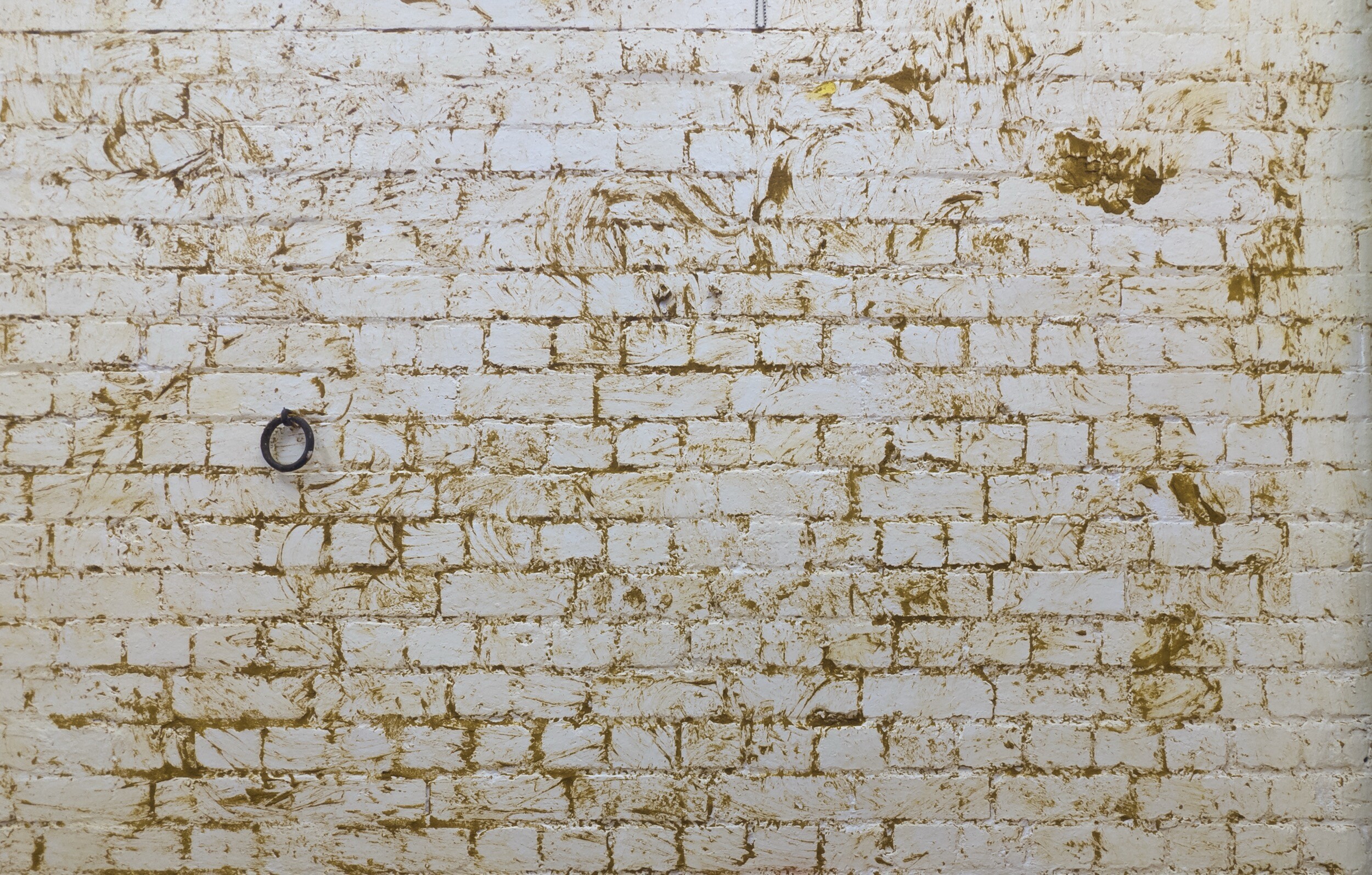

Stolen Wages Common Life: Mervyn Street Paintings

We walk off after song’s eclipse, walkabout’s extensity, a season been said goodbye to and hello the cattle who’s all lined in a row and whose tails become the whip. How could you get past the bad smell of it all, when the very territory that makes flight possible is itself the zone of enclosure and relegation from which you must become outlaw? In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, cattle and sheep stations in the north of the country displaced Aboriginal populations, gutted homelands, and were precipitated by massacres and summary killings. Spearing a cow for something to eat, or as strategy to combat pastoral settlement, could result in the punishment of death. Yet, some of these stations are spoken of with fondness by mob who worked on them, and as “enclave[s] of stability within their landscape of terror.”

Exclusive to the Magazine

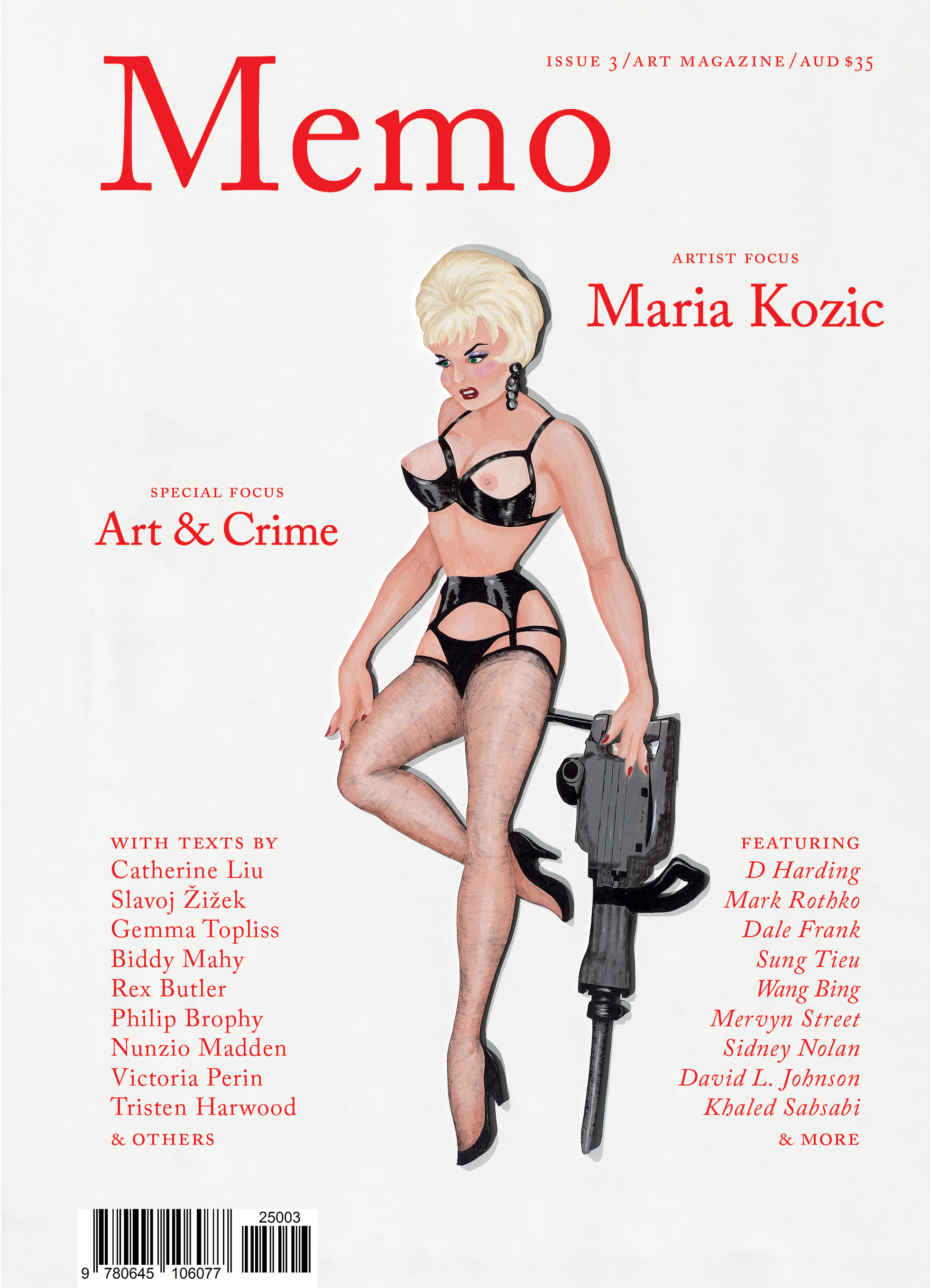

Stolen Wages Common Life: Mervyn Street Paintings by Tristen Harwood is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

Isa Genzken’s 75/75 retrospective at Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie lands her sculptures in a glass-walled “lobby,” a space between utopian modernism and corporate sterility. From her precise Ellipsoids to chaotic assemblages, the show clarifies her art’s ongoing friction with architecture, history, and sculptural convention.

From borrowing Tarkovsky at the UQ library to representing Australia at the Venice Biennale, Archie Moore’s art interrogates memory, history, and place. But what role does cinema play in his practice?