MK Matrix

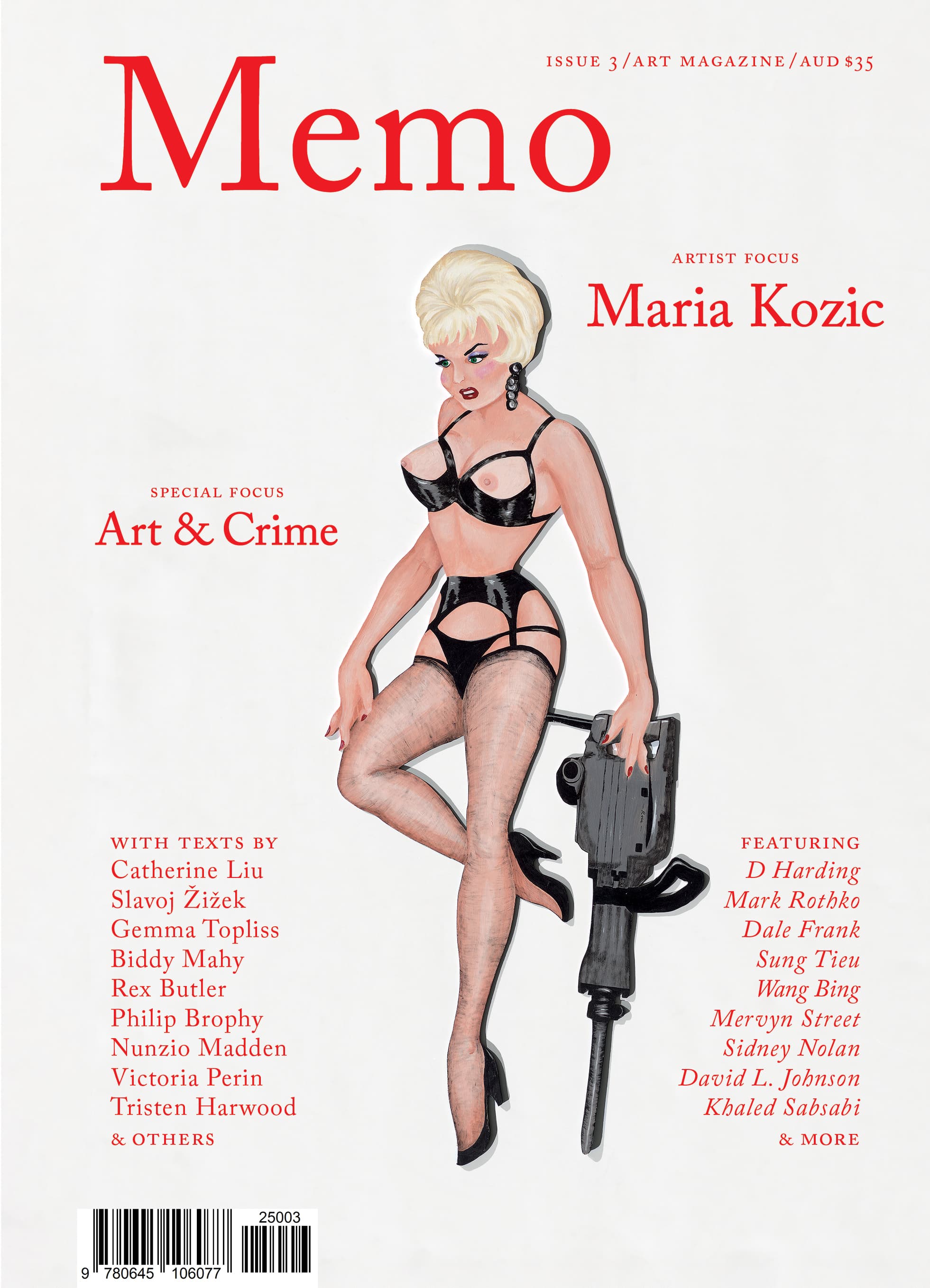

Seriality animates Maria Kozic’s art in 1990s Melbourne. Her fleshly weapons and pin-up girls mutate across media, trace the tangled circuitry of sex, violence, and mass culture’s compulsive pulse.

In his essay “The Desire of Maria Kozic,” published in Art & Text’s Winter 1981 issue, critic Adrian Martin highlighted the significance of repetition in Kozic’s work—a repetition not in the tradition of pop art, but one intrinsically linked to desire, as “manifested through … multiplication, flow, (and) intensity.” Repetition has remained central in discussions of Kozic’s work, but here, I want to introduce a related yet distinct concept: the serial. Repetition can be seen in the industrially reproduced blocks of Minimalist art or in two different prints from the same Warhol screen. It operates through sameness—by reproducing a singular thing over and over, it either intensifies or numbs its essence. The serial, by contrast, implies multiplicity. Rather than a single entity repeated, it consists of a group of individual works that share a common origin—like a series of panels in a comic. The serial is defined by progression, unfolding as a sequence, whereas repetition is a meditation on a single form. If repetition is the clone, then the serial is the mutant. The serial is closer to the concept of siblings—distinct yet connected, evolving rather than merely recurring.2

Exclusive to the Magazine

MK Matrix by Gemma Topliss is featured in full in Issue 3 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

The APY Art Centre Collective scandal, ignited by Murdoch’s The Australian, exposed more than allegations of interference—it revealed power struggles in the Aboriginal art industry and became a flashpoint for culture wars. As institutions, dealers, and politicians jockeyed for position, the artists were caught in a battle over authenticity, control, and the future of Aboriginal contemporary art.

By recasting Black-Eyed Sue and Sweet Poll in shackles, Sayer’s 1792 engraving subverts the sailor’s farewell to reveal convict and naval cruelty as mirror images.