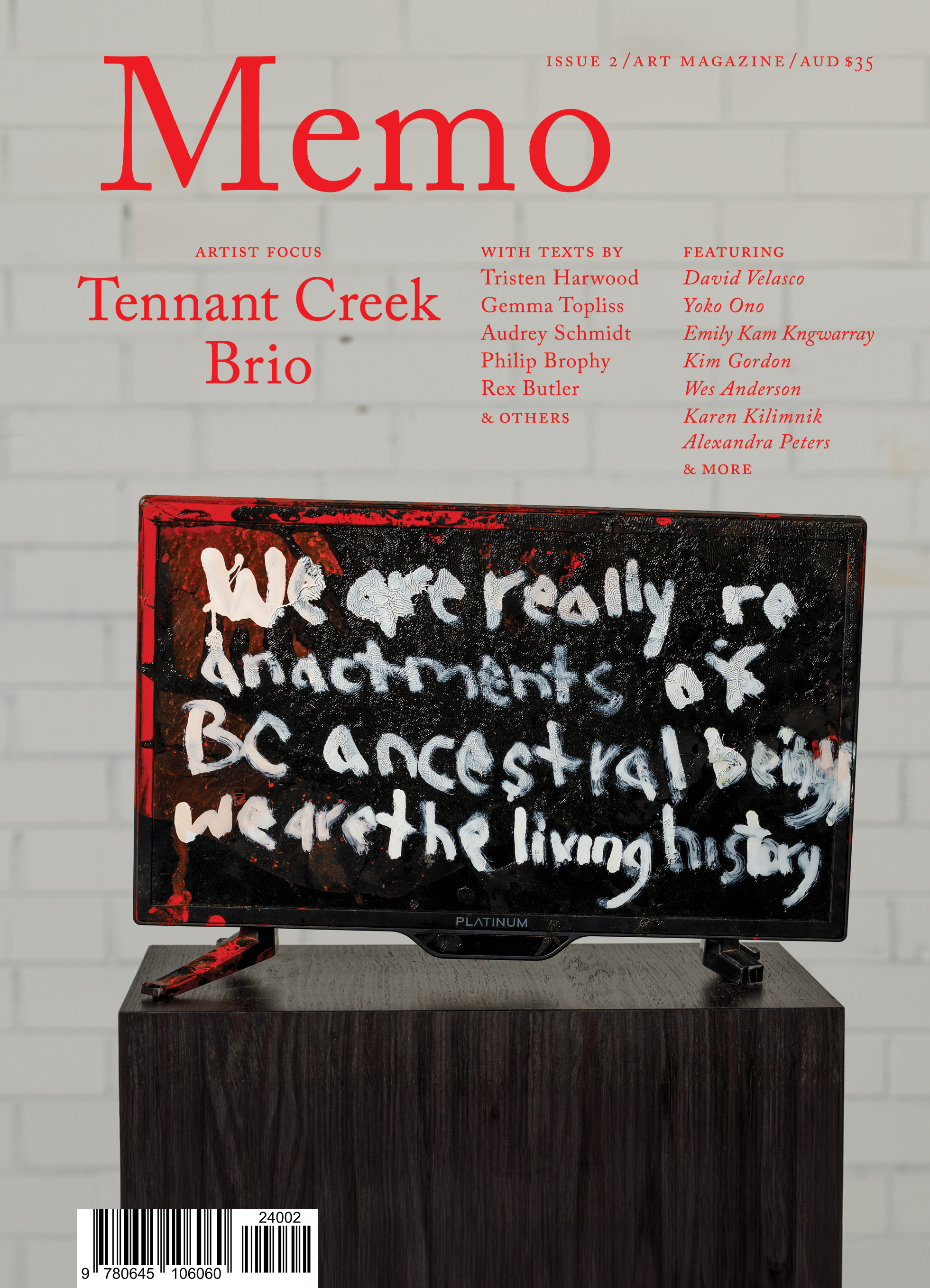

Monsters of Energy

The Tennant Creek Brio’s art isn’t a legible script, a tidy lineage, or an easy metaphor—it’s a rupture, a refusal, a site of resurgence. This story sends us somewhere else, reaching for something that came before or after, looking for what’s out back, round the back of the house, the shed, the art centre, the “outback.”

Everything about him was red. His red snout, the morning red, he dreams red, the red wind, and the land is scraped stiff red by the hooves of his cattle. At dawn red. In this part of Country, the dried-out beauty is red dirt and when its heart beats — our hearts, which are mostly water, beat, because they too are coloured red. For millions of years there were no hooves, no dynamite, no excavators to scrape this land stiff. But they came and there was a red wire that splintered across the sky casting its shadow on the dirt. The world was split in two — our hearts permanently cloven.

Exclusive to the Magazine

Monsters of Energy by Tristen Harwood is featured in full in Issue 2 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Related

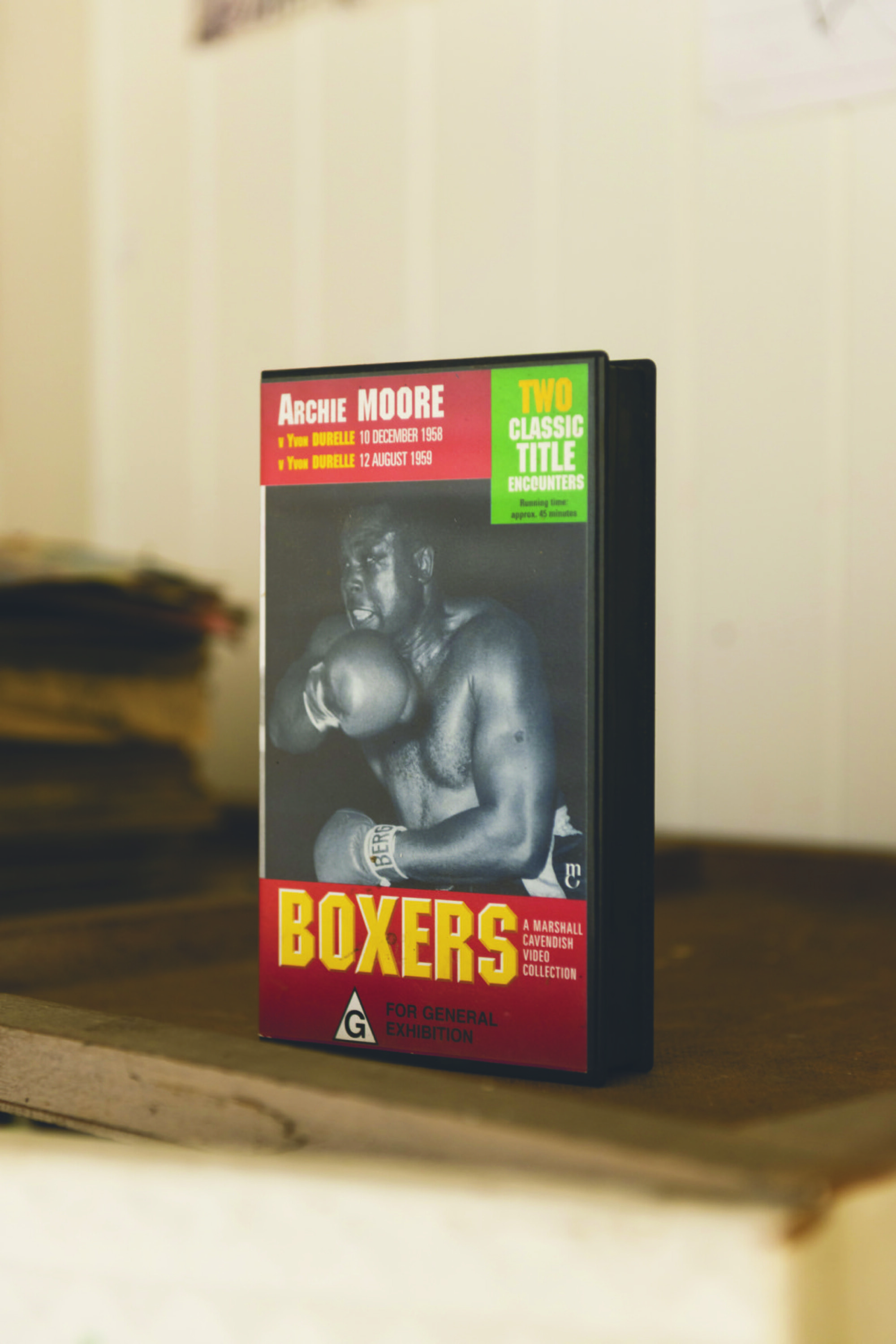

Boxer, scrapper, parry—Archie Moore’s work moves through the tropes assigned to him, resisting, reworking, refusing.

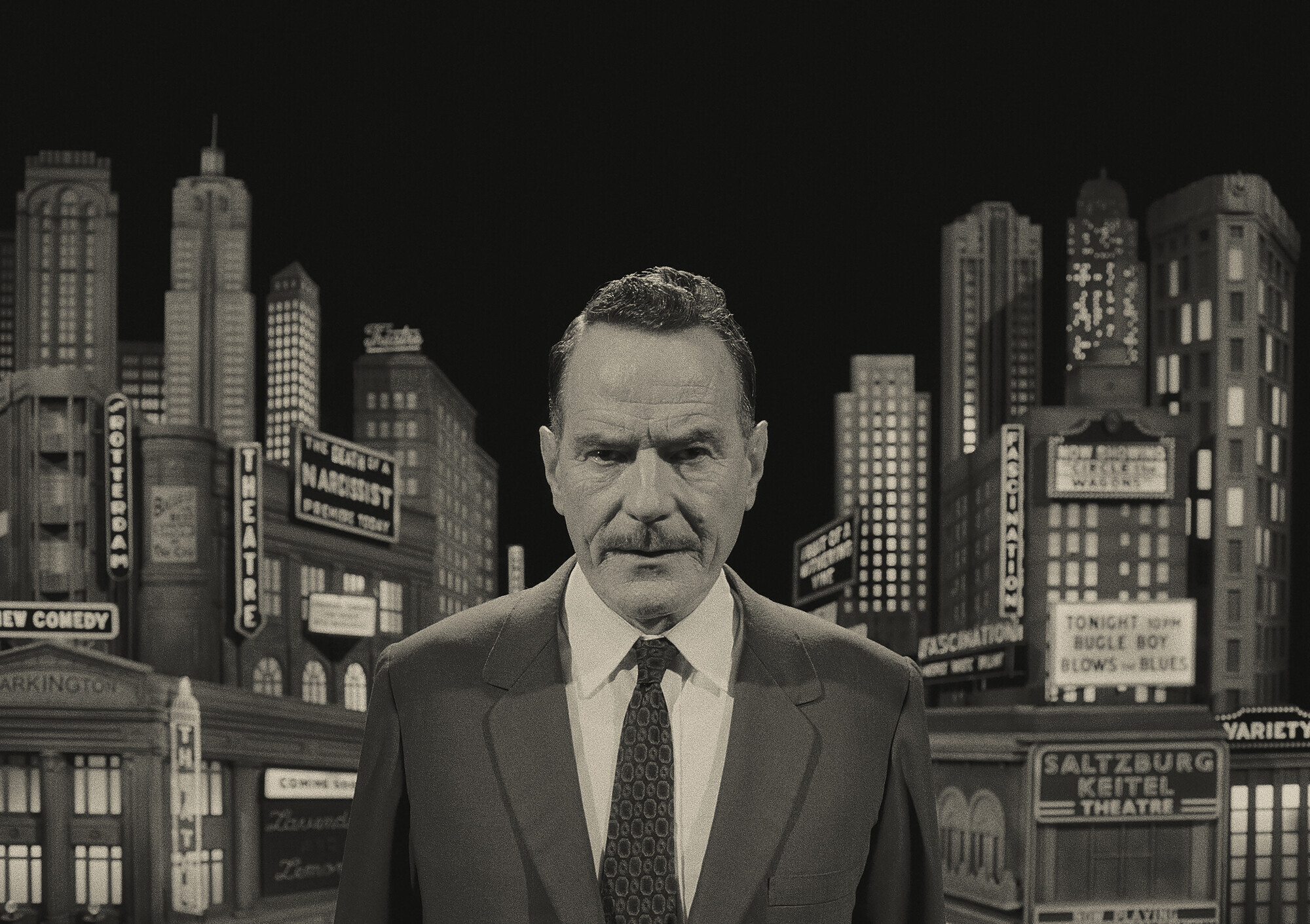

At a time when all these elements are easily replicated by AI and memed on social media, what is often called Anderson’s “twee” aesthetic continues to be derided as all style and no substance.

The APY Art Centre Collective scandal, ignited by Murdoch’s The Australian, exposed more than allegations of interference—it revealed power struggles in the Aboriginal art industry and became a flashpoint for culture wars. As institutions, dealers, and politicians jockeyed for position, the artists were caught in a battle over authenticity, control, and the future of Aboriginal contemporary art.