Technical Knockout

Boxer, scrapper, parry—Archie Moore’s work moves through the tropes assigned to him, resisting, reworking, refusing.

By Tristen Harwood

Issue 1, Summer 2023/24

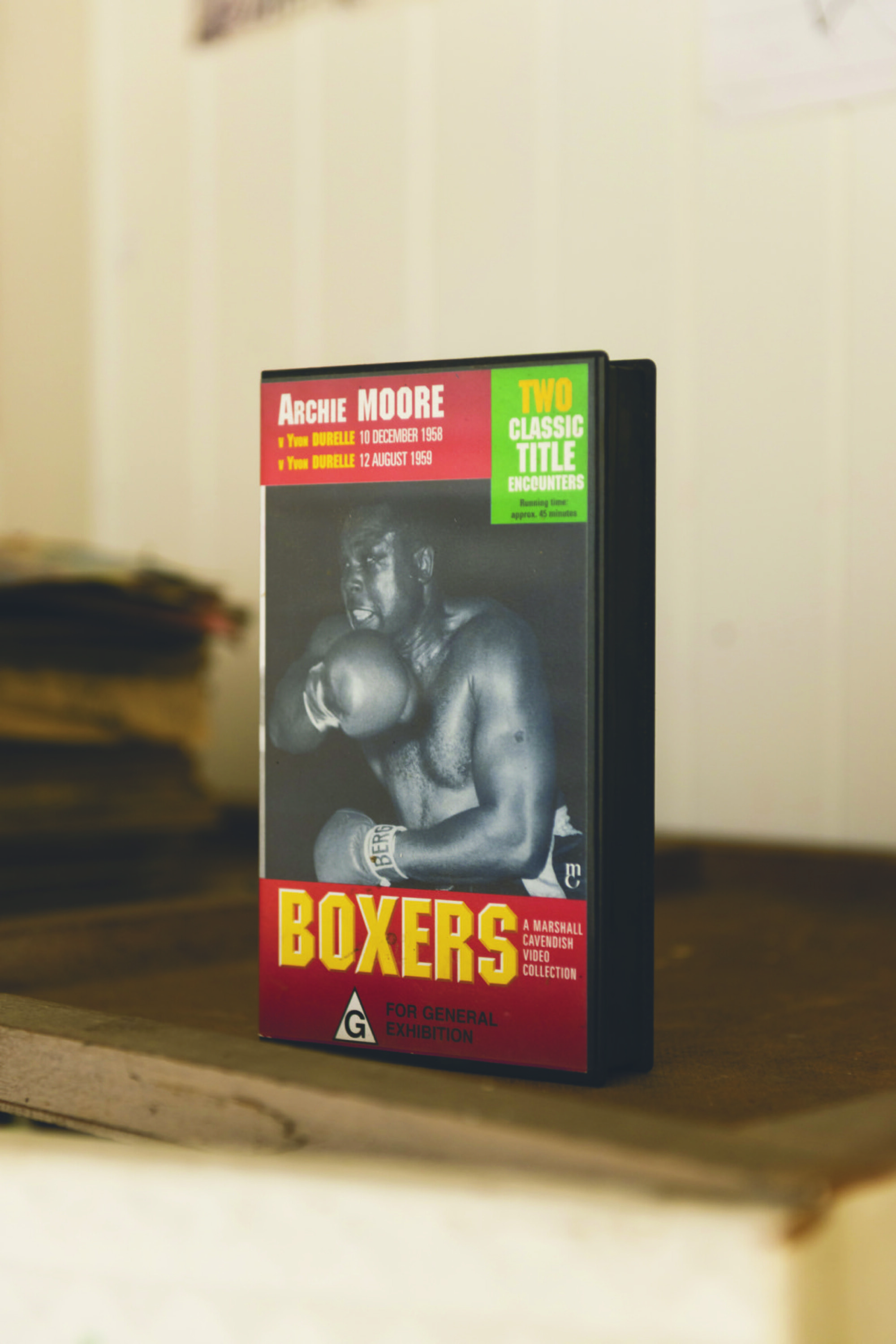

Boxer. All lives have their tropes. You could be the boy from the bush or the city Blak. Maybe cynicism is your thing. The artist or a mechanic with the calloused hands. You’re always the wittiest one at the party or the drunk or a ghost. You can choose, but sometimes you have little control. If you are the artist, curators and art historians and critics will assign tropes for you: now music is your thing. You’re the movie lover. The one with the boxer’s name. No. The boxer. Or it’s that you’re plagued by memory like the empty hole that’s been dug over the past couple-hundred years (Diane Seuss, Frank Sonnets, 2021). Consider this. Archie Moore’s father named him after the World Light Heavyweight Champion boxer Archie Moore. He is the third-best boxer of all time. At the level of the symbolic, boxing leaves no ambiguity.

Exclusive to the Magazine

Technical Knockout by Tristen Harwood is featured in full in Issue 1 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.

Buy this article as an ePaper (PDF)

Single-article PDF, not the whole issue. AUD $5.00.