I Am a Serious Artist: Contemporary Artists in Contemporary Hollywood

Hollywood thinks it’s exposing the art world’s grift, but it’s just another con. From Velvet Buzzsaw to Picasso Baby, cinema keeps repackaging conceptual cringe as critique—while artists play along. If contemporary art is now just another film genre, it’s a bad one.

By Philip Brophy

Issue 1, Summer 2023/24

If Art Basel at Miami Beach (AB@MB) wanted to make a movie, they were relieved of the drudgery of doing so when Velvet Buzzsaw (2019) hit Netflix. Jake Gyllenhaal plays a pathetically cynical art critic, swanning around contemporary galleries in Los Angeles. He encounters the “undiscovered” paintings of a deceased artist named Vetril Dease. (They are all rote gothic narratives: think German artist Jörg Immendorf meets Iron Maiden’s Eddie the Head done à la Lucien Freud.) Dease has used human blood mixed with paint, so anyone who buys or trades in these paintings dies a gory death. The film’s marketing tags it a “camp horror” — and if you believe that, you must be Ken Russell. Velvet Buzzsaw is simultaneously a perfect snapshot of AB@MB’s Floridian hustle that suckers le dumb riche into buying “crapceptual art” (think Joseph Kosuth at a Costco stall at Coachella), and a film that performs the same hustle to a streaming audience who can be suckered into believing that this is how the “art world” operates.

Exclusive to the Magazine

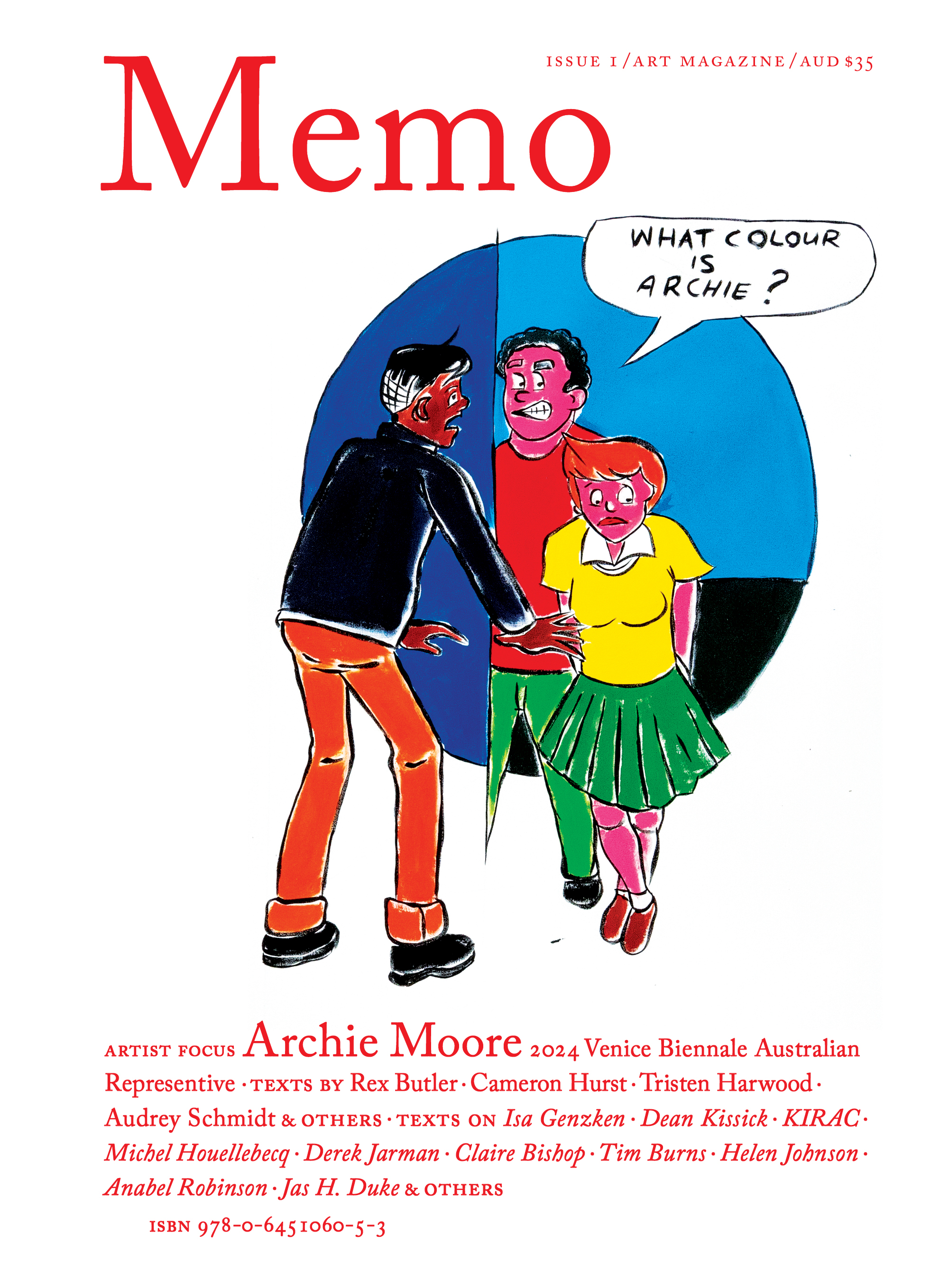

I Am a Serious Artist: Contemporary Artists in Contemporary Hollywood by Philip Brophy is featured in full in Issue 1 of Memo magazine.

Get your hands on the print edition through our online shop or save up to 20% and get free domestic shipping with a subscription.