Brook Andrew: The Language of Skulls

Paris Lettau

It’s quite rare to encounter the work of an artist and feel like you have to re-ask yourself such basic questions as “What is an image?” and “What does an image do?” But these questions are addressed to us in Brook Andrew’s current show The Langauge of Skulls.

Located in Glen Iris, Ten Cubed takes its name from the mandated logic of the gallery’s collection: ten artists from Australia and New Zealand are being collected over ten years with a minimum of ten works per artist. Andrew enters as part of an extension—called Ten Cubed 2—of the original collecting project which aims to extend the collection to international artists. Just nine works are on display in this show, however, a number of which have been selected not from the collection, but from Tolarno Galleries, who represents Andrew in Melbourne.

The curation of the works—all screen-prints on canvas, with some collage elements—is striking. This is unsurprising given Andrew’s strongly self-curated survey show at the National Gallery of Victoria last year titled The Right to Offend is Sacred, which saw the artist take the ‘archival impulse’ that has been evident in his practice to new heights (and surely gave him the strong standing he needed to be selected as the curator of the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, taking place in 2020).

The gallery itself is long and narrow, and the section of the walls on which works are hung is distinctively painted as two horizontal bars of white and black, immediately framing the work in a symbolic space of difference, contiguity and exchange. This recalls the plural presences and imaginative alliances constitutive of Andrew’s practice.

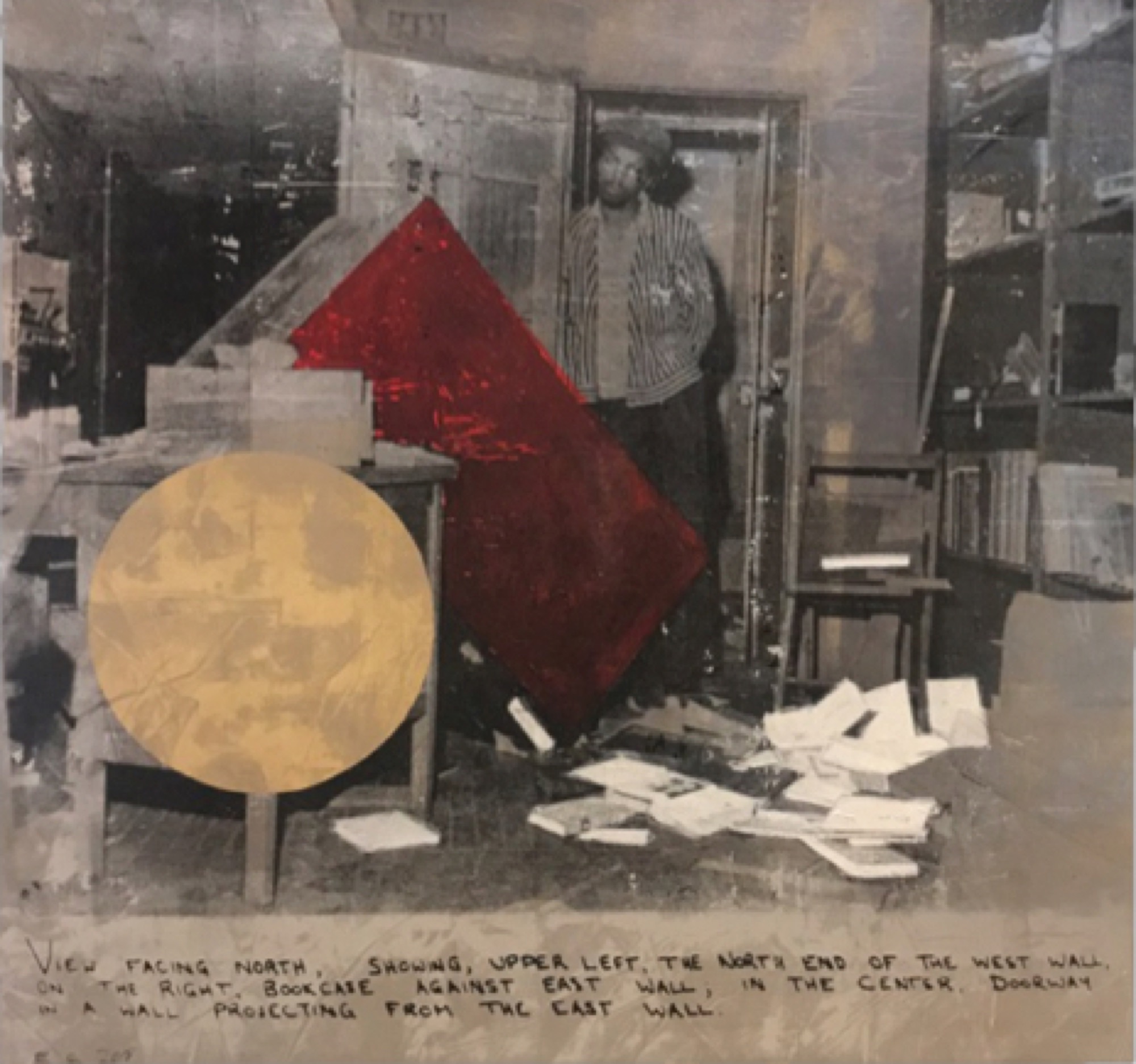

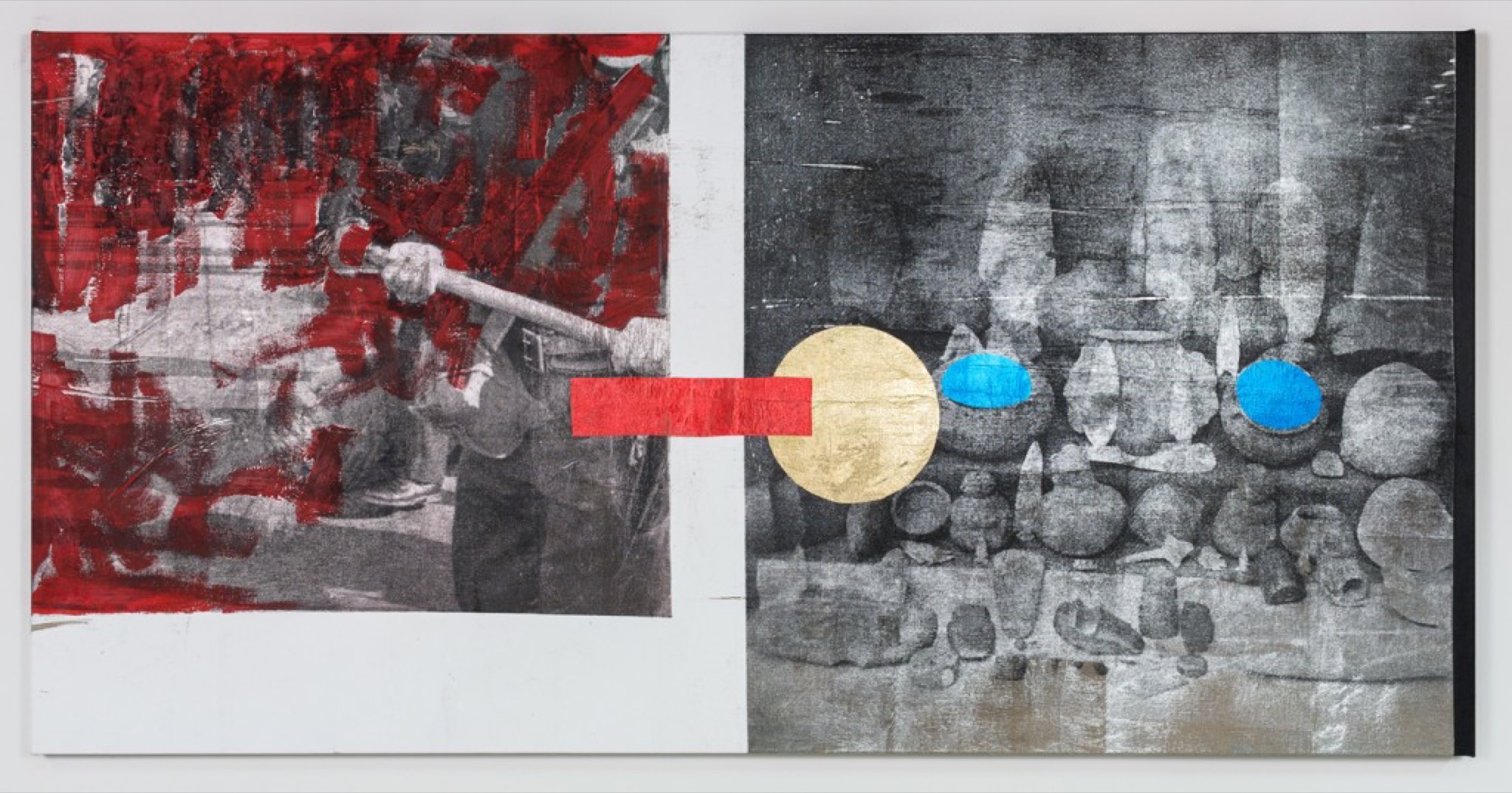

The exhibition displays many of the distinctive qualities of Andrew’s practice, in which elements of advertising, Pop, Minimalism and Russian Constructivism are combined with largely ready-made imagery sourced from photography, news media, archival collections and postcards. Office I, 2018, for example, combines archival material with a Pop-like sense of composition and minimalist use of primary colours (it somehow even recalls Richard Hamilton’s 1956 collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?). Unlike Hamilton’s Pop, however, Andrew draws on layers of cultural and historical “archaeology” of the colonial and postcolonial world, as seen in most works on display in the show. Thus the show demonstrates Andrew’s ongoing commitment to creating compositions that present transcultural histories and postcolonial constellations in open, dialogical and non-didactic ways.

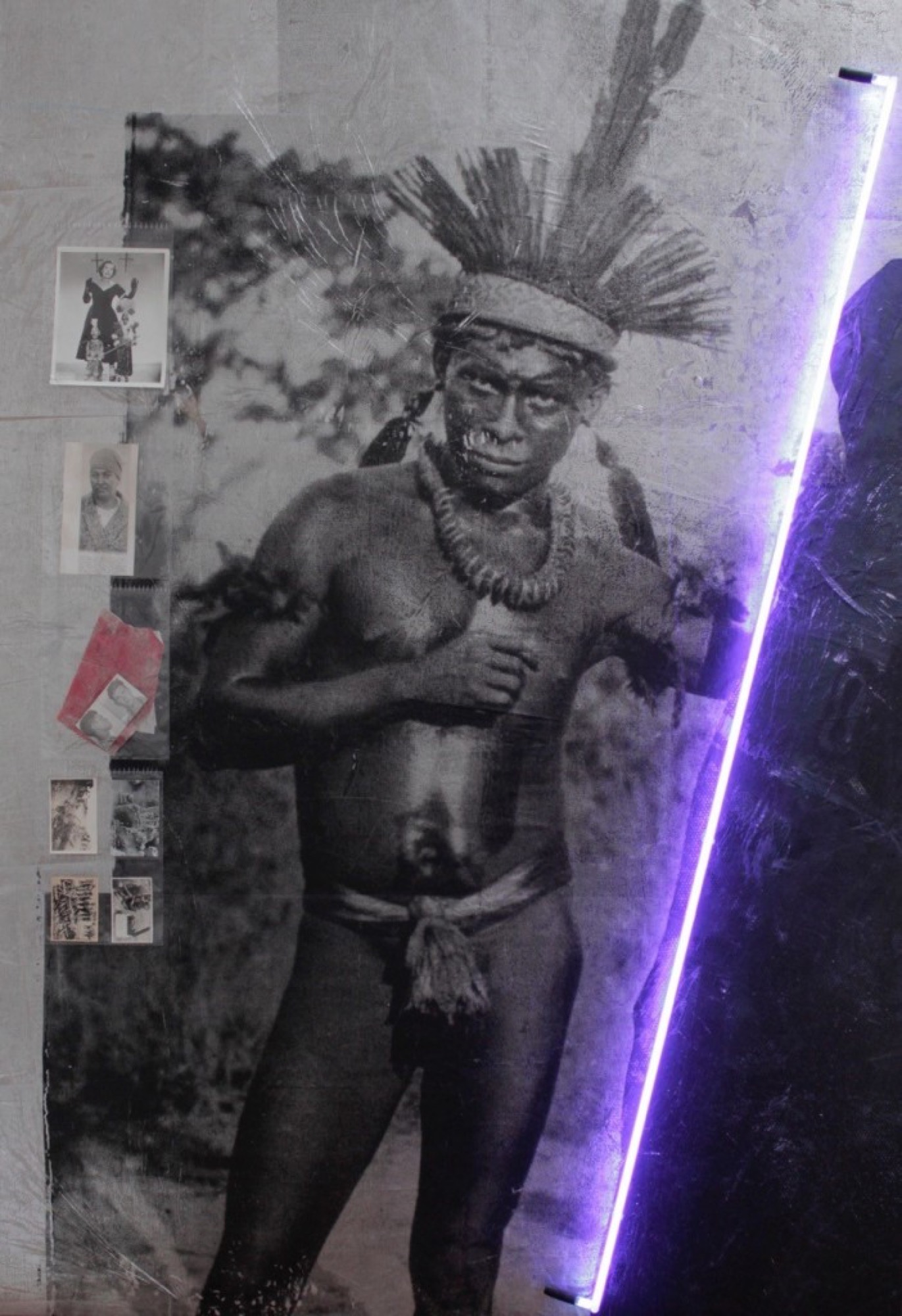

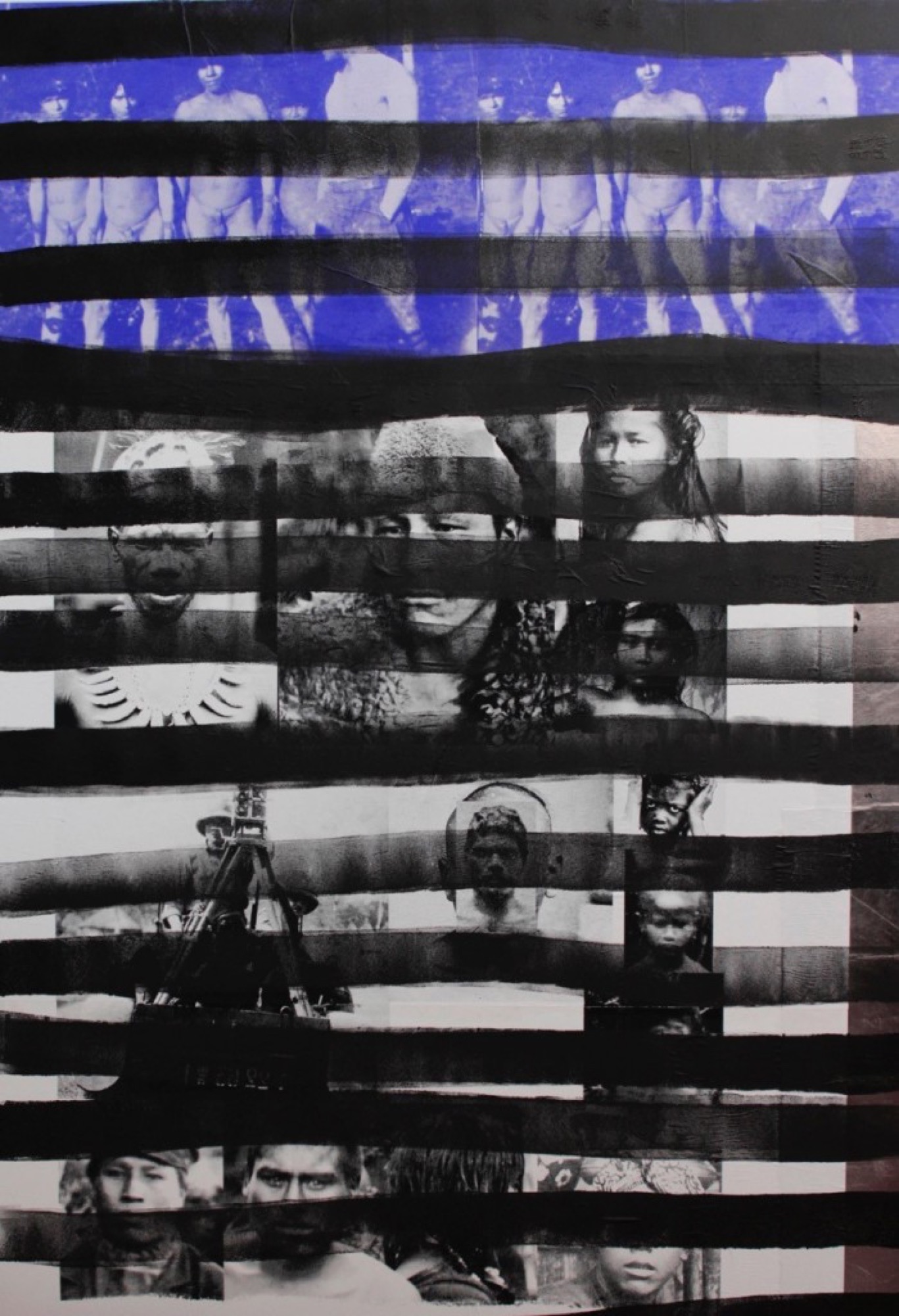

Also evident in the exhibition is Andrew’s strong sense of design and the poetics of materials and form, which come together in his collages and assemblages. This is seen in the sensitivity to materiality that is manifest in Horizon (2017), for instance, which broadly recalls Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings. In Systems II 2016, too, which stands on the floor like a gallery-goer calmly leaning against the wall, Andrew’s use of archival material is compelling not only in its overall design (its central anonymous archival figure standing before the spectator with a parallel purple neon emitting light that touches work and viewer as if enlightening both their auras), but also in the gentle suggestions of historical cohabitation of work, viewer and various archival material held in plastic sleeves that are hand-stitched onto the canvas.

If Andrew’s work looks like a number of leading international artists (such as the perhaps more famous Kader Attia, whose room size archival installation was a standout at Documenta 13), he can also clearly claim the mantle of a previous generation of leading Australian post-colonial ‘appropriation’ artists like Gordon Bennett and Tracey Moffatt. Unlike that generation, however, Andrew generally draws on his personal collection of historical postcards, textiles, photographs, cultural objects, newspaper cuttings, and books—all of which can be seen in works exhibited in The Language of Skulls—which document very localised (though still global) histories not immediately recognisable by the viewer (perhaps partly owing to the subjective nature of Andrew’s personal collection).

These are images that have hitherto been preserved by various systems of exchange, or by physical archives and their curators. This makes the images that materialise in Andrew’s practice what theorist Boris Groys calls ‘weak images’, not because they are visually uninteresting, but because they have been dependent on the specific spatial and temporal systems of their preservation and protection. ‘Strong images’, on the other hand, maintain their identity in space and time due to unthought frames of collective consciousness and memory. Unlike Queen Elizabeth, Eddie Mabo and Trucanini, for example—whose image will flash spontaneously before the mind of most readers—the weak archival image sits silently awaiting its retrieval and presentation or exhibition before the senses of the viewer. This ‘weakness’ is exemplified by the anonymity and obscurity of Andrew’s various archival personages and events (whose unknown significance the viewer is perpetually alienated from), presented either as pasted cut-outs or stitched (via plastic sleeves) onto the canvas surface in works like Systems II 2016, Horizon 2017 and Another Day 2018.

At the level of form too, the references are weak. If Andrew draws on hints of pop, constructivism and minimalism, these hints (like the archival sources) have an anonymity because they are inferred and conjectured rather than immediately recognised. There are none of the strong, iconographic art historical references to Mondrian or Stella (Bennett), no moody atmospherics of Namatjira landscapes (Moffatt), no terse irony of Lichtenstein Pop comics (Bennett, Bell), nor even the faux-gothic decorative screen-prints of David Noonan.

Andrew thus gives these weak images a new ground (often a blank monochrome silver canvas seen in works like The Language of Skulls, 2018, Another Day, 2018, and Horizon 2017) that feels at once mythic and positively historical. These blank canvas grounds even recall Warhol’s monochrome (also often silver) canvases onto which he screen-printed Elvises, Liz Taylors or Jackie Kennedys in the 1960s. Yet Warhol presents strong icons of celebrities drawn from the mass media, whereas Andrew shows secret communions between marginal places and times. In Andrew’s work, archival images thus point to absent historical content, forms of domination and scientific shapes of consciousness: in short, to the systems of power and knowledge that produced them, be it phrenology (The Language of Skulls 2018), ethnology (Systems I 2016), militarism (Another Day, 2018), or the fanatic religious missions of Mission de l’Esprit Saint (Clown, 2018), to name just a few.

It is tempting to argue that because Andrew presents this archival content in works of art, he therefore transforms it into the form of strong images, giving it a new voice and agency, endowing it with presence and aura. The art context transforms things into powerful images because it imposes on the spectator a wholly new attitude to the object before them. But perhaps most interesting in The Language of Skulls is that at the level of the exhibition as a whole, even Andrew’s works seem partly emptied of their aura due to having a similar status—as components of the exhibition—that archival images have as components of the works of art. Individual works of art are in a certain way ‘reduced’ to elements of a larger curatorial design.

This could just be a testament to good curation. In Andrew’s work, however, it also reads as meaningful because it focusses attention not so much on the individual works of art, but on a greater scheme of mythic connections in which, like archival images, the work of art is itself a kind of memory-trace living in an after-life. The works become like halfway images standing on both sides of a boundary of identity: as autonomous works of art and at the same time elements of a grander, as yet unknown, composition. In The Language of Skulls, this tinges Andrew’s works with a similar sense of the dialectics of frailty and strength that archival material has in its after-life, as if Andrew is beginning a process of entering his own work into the immense web of interconnected histories and times from which he sources his imagery.

Paris is a writer from Melbourne.