Tertulia

Bianca Winataputri

The term “exchange” calls for active listening, engagement in a dialogue and, at some point, the establishment of a common ground. BLINDSIDE Gallery’s recent exhibition Tertulia speaks to this theme, bringing together moving image works from artists residing in Australia and Mexico: Julia Barco, Ximena Cuevas, Nasim Nasr, Yandell Walton, Dalia Huerta and Ivan Puig, as well as commissioned writers responding to the works, Alejandro Del Castillo, Gabriella Muñoz, Gonzalo Varela, Makayla-May Brinckley, Sara El Sayed, Scarlett Evans and Rebecca Perich.

Tertulia is co-curated by Claudia Hogan (Australia-born) and Carla Serrano (Mexico-born), who became friends when they both studied a masters of arts management at RMIT. In the exhibition catalogue, the curators state: “Throughout our many conversations, we have often shared views to consider the cultural and artistic climates of our two countries of origin. Within these exchanges, reflecting on pressing issues that are topical within a global perspective, we found that our cultural positionings helped frame and inform the nuanced understandings between us”. The exhibition is framed by this central theme of dialogue, which is also echoed in its title. ‘Tertulia’ is a Spanish literary salon/social gathering established in the 17th century, which was initially held in private homes. Over time the practice expanded to public spaces including bars, clubs and cafés. These gatherings typically consist of artists, writers and poets, who come together to present their works and share feedback. In this same vein, the exhibition catalogue features newly commissioned writings in response to the works of art displayed, written in either English and Spanish.

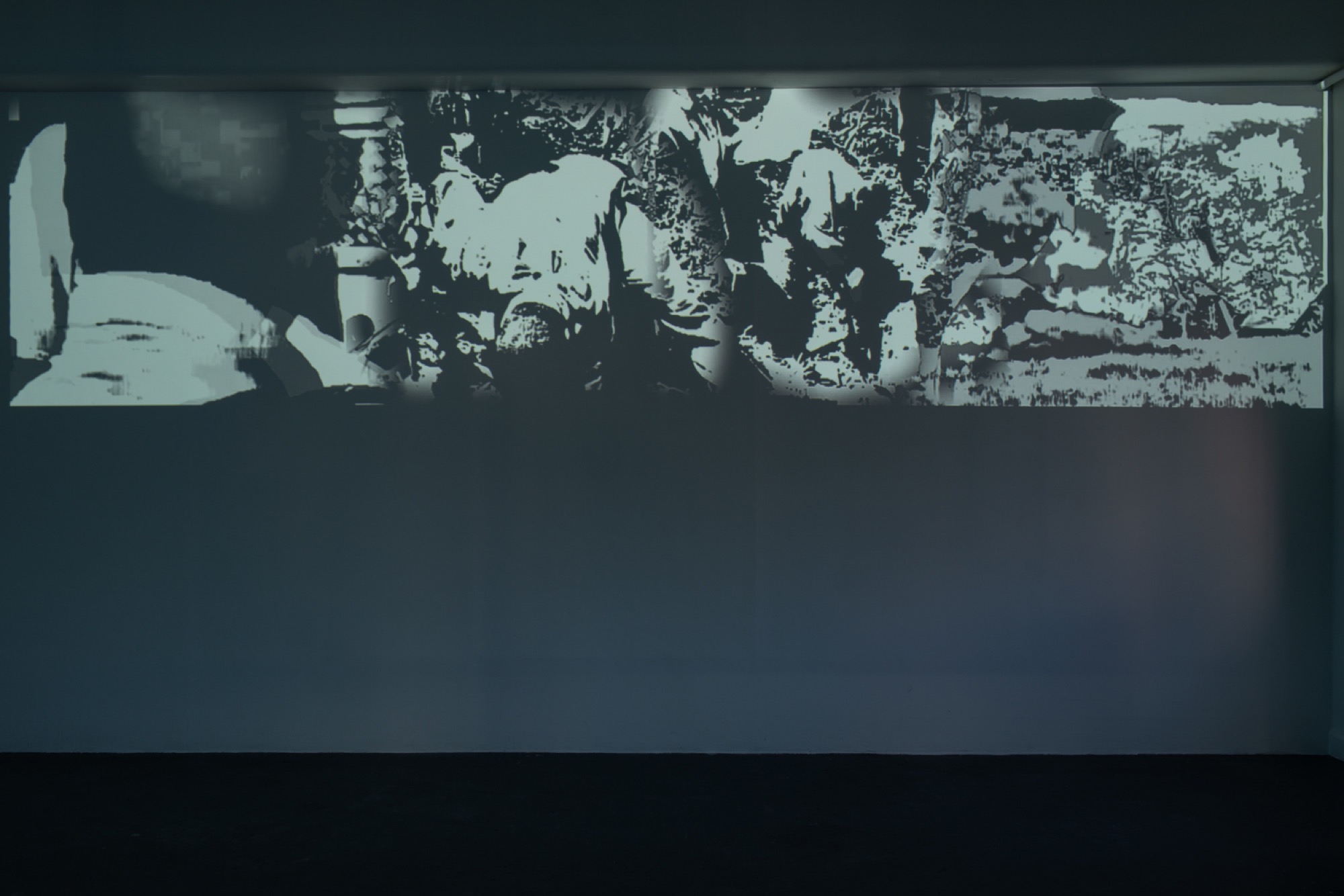

After opening at BLINDSIDE Gallery for two weeks, Tertulia shifted to the virtual space following returned lockdown measures in Melbourne. Entering the virtual gallery, we are greeted first by Julia Barco’s black and white video installation Duelo (2013), which was originally produced as a 12 x 3 metre mural, allowing viewers to be completely immersed in the work, but which has now been re-adapted to fit the gallery space. The moving mural stitches images and footage taken from acts of violence that occurred in Colombia, particularly during the first decade of this century, depicting scenes of explosions overlaid with images of local residents fleeing their homes and children finding shelter.

Barco’s stencil-like images are a deliberate nod to the aesthetics of urban murals. This technique blurs the identities of the people in the footage without erasing their expressions, inviting us to connect with the work from a more emotional and humane standpoint. The work’s location is not revealed. The abstract images, instead, allow for the possibility of this occurrence happening anywhere and everywhere—suggesting that violence is not specific to one place, race or culture. Rather the work invites us to contemplate and reflect, to find out more about where, when and how this happened in Colombia and elsewhere. As Barco states, “I wanted to produce a work which could serve, as Susan Sontag wrote, as a memento mori, to foster contemplation and meditation on violence, and, to use Doris Salcedo´s term, to serve as a place of memory, where mourning can be lived out.”

Adjacent to Barco’s moving mural are two of Ximena Cuevas’s video works: Bleeding Heart (1993) and Natural Instincts (1999). Paired together in the space, Cuevas’ renowned works explore themes of gender and national identity through music and elements of pop culture. The artist plays with truth and fiction, challenging the seemingly ‘impossible’ versions of reality found in everyday life. I was particularly interested in the writing produced by Wiradjuri writer and researcher Makayla-May Brinckley in response to Cuevas’s Natural Instincts, which offers a different lens for experiencing the work.

Cuevas has described Natural Instincts in the past as “a video of musical terror where I superficially look at one of the Mexican phenomena that horrifies me the most: internalized racism, being ashamed of one’s own roots, the fantasy of waking up white.” Brinckley, meanwhile, recalls the first time she learned of her heritage as a Wiradjuri woman:

I don’t remember when my mother first told me of our family heritage;

I know I was young and old at the same time.

Too young to question why I was born into this culture

But not taught it from my beginnings.

Too old to feel I had a right to be angry.

Surely she kept it with reason.

Let us think but not speak of this

Intergenerational trauma,

Colonisation,

Internalised racism.

Let us think of your blackness being ripped from your body.

Mind and body filled with silence

Of being ashamed of who you are.

When I knew

That this body is one from the Wiradjuri land:

Feelings of surprise

of joy

betrayal.

Brinckley’s response demonstrates that there is no one way to experience a work of art. Providing such opportunity for Brinckley to respond to Cuevas’ works returns again to the concept of exchange as active listening and response, which incorporates various standpoints. These written responses add another layer to approaching works of art that each of us as viewers also have the opportunity to add to and make our own connections with.

Listening is a central theme in Tertulia. Nassim Nasr’s Beshkan (Breakdown) (2013) examines the different and perplexing ways we comprehend and interpret. The work displays a row of hands doing the “Persian snap” (beshkan–بشكن), a traditional form of celebration in Middle Eastern countries, that involves the clicking of fingers. Viewing this for the first time, one can feel that the work is trying to communicate a sentence, a phrase or perhaps even a story. Evidently the work displays nothing more than a celebratory gesture, but it is the viewers’ varied reactions to this finger snapping that in a sense ‘completes’ the work. What is viewed as joyous in one culture can be perceived as sinister and rude in another (for example, snapping your fingers to get someone’s attention). Nasr inspects the complex and contradicting ways in which culture is viewed, experienced and understood, in which one simple action or gesture has multiple meanings that have developed over each distinct history. In the context of Tertulia, exhibited and displayed to a primarily Australian audience, the perceptions of the work and gesture will almost definitely vary. Similar to Barco’s moving mural, this work invites us again to learn and further investigate.

Shared human experiences is another common thread. The cultural exchange framework of Tertulia helps position our varied understanding of the world we live in, while also exposing the responsibilities we carry. Works in the exhibition expose such topical issues as climate change and extinction. The short film CÅSUCKA (2016), written and directed by Dalia Huerta and Ivan Puig, follows a man’s journey in a dystopian future where he is the last of his race. The vast landscape, complete with huge, overwhelming cactuses, highlights the triumph of nature against human existence. In his written response to the film, Alejandro del Castillo follows on this thread:

You just have to look up:

a flowerpot hangs from the beam.

It contains a floating universe, in which a little plant gives flowers whose fruit worms eat;

life goes by without much noise,

Life is a motionless silhouette.

Always silent

Will it not be dissected?

Someone coughs.

Deer eyes. Lemur eyes. Future eyes that look at you from their absence; are buried stories

on the white plates of a museum.

The struggle between human versus nature is also explored in Yandell Walton’s Submerged (2017). A site-responsive projection installation, Walton’s work depicts a young woman floating submissively in a body of water. The water’s luminescent blue glow can be seen from outside the gallery, as the work is tucked directly behind the entrance door and projected upright to the ceiling. This positioning creates an overall sense of being trapped. At once beautiful and tragic, Mexican-Australian writer Gabriella Muñoz likens the work to Ophelia and associates the body of water to mother nature and lullabies comforting the young child. Submerged expresses the tensions between our built environment and nature’s forces and the temporality of our present situation, with Muñoz’s response reminding us that there is still time to change and make amends.

One of the most compelling aspects of Tertulia is the relationship drawn and nurtured between works of art and commissioned texts. Each response adds another angle to the works displayed. A dialogue is produced. These texts could be read independently from the works of art and vice versa, but together they create a synergy that ultimately reveals the fluidity of arts and cultural practice across national borders. It is perhaps a missed opportunity to have the texts only accessible through the online catalogue as opposed to them having a more prominent presence within the gallery space. I found that there was almost an equal bearing between works of art and texts produced for this project that not only support the curatorial premise/historical reference to “Tertulia” but also further enhance the concept of exchange and listening that the exhibition seeks to point out. Regardless, I suggest viewing the works with the catalogue in hand.

It is also worth noting that Tertulia acknowledges the multiplicity of identities and identity-making in our global environment. The exhibition focuses on Australian/Mexican artistic and literary exchanges, but refuses the geographical boundaries or definitions of the two regions. Australian artists featured in the exhibition are selected not based on where they were born or what their heritage is, but simply by the fact that they reside here in Australia. If ‘exchange’ includes finding a common ground, it certainly isn’t dictated by biological or geographical definitions in this project.

At a time when we are more polarised, separated and divided from one another, particularly ideologically, Tertulia demonstrates the importance of cultural-exchange projects, which are otherwise lacking in the current arts scene. Hogan and Serrano have carefully selected works and corresponding writers that allow us to become active participants of exchange no matter who we are or where we come from. This approach of moving beyond common narratives surrounding race, heritage and geographies allows for much deeper, critical reflections to take place about our collective identity and responsibilities. Whether it be issues of violence, the climate crisis, racism, unconscious biases, we all have a part to play.

Tertulia is ongoing virtually.

Bianca Winataputri is a Melbourne-based independent curator, writer and PhD candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash Art, Design and Architecture (MADA). She is currently Public Programs coordinator at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) and was recently Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Australia, where she was part of a curatorium for the major exhibition Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia.