Luke Sands

Helen O'Toole

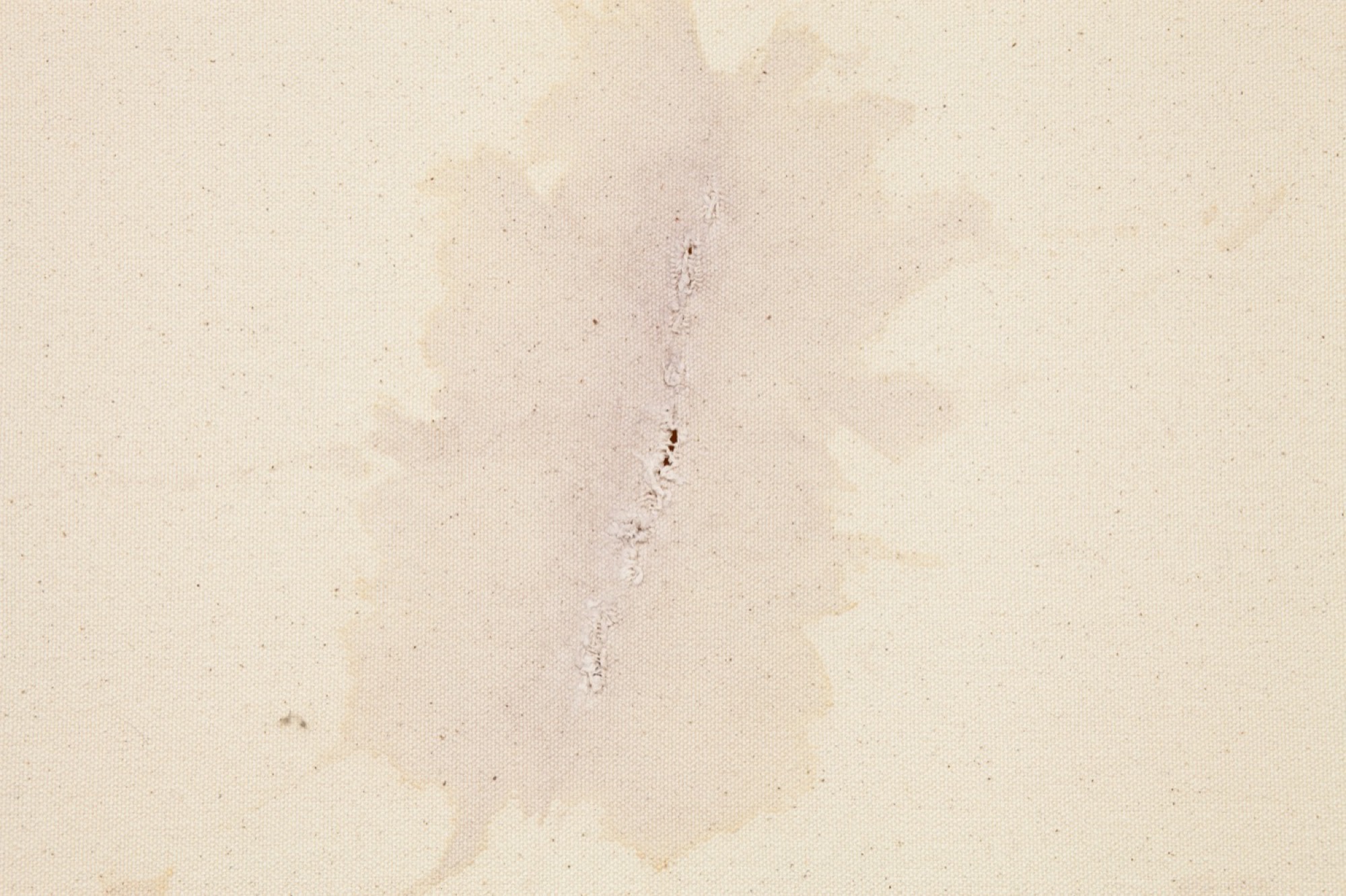

Luke Sands has long been interested in the mouth as a technical support for the production of art. His Mouthal sculptures (2014–15), for instance, were made from chewing a range of materials (like books, receipts, metal keyring parts, electrical wire and toy clothing), using saliva and the pressure of his tongue and teeth to bond them together into small, compact forms. Sands' singular 1.84 x 3.13-metre-long Untitled “chewed canvas” at Guzzler—a white-cube art gallery with a dirt floor in a garage out the back of a Rosanna share house (a suburb in Melbourne's north-east)—represents his most recent undertaking in this vein. The unprimed cotton duck canvas is pocked by a number of linear holes, which the artist produced by chewing on sections of the unstretched canvas for roughly one hour a day, every second day, over a period of one month.

The canvas is only sparsely populated by these holes—indicative of the physical limitations imposed on the artist by his process (namely, stress to his teeth, which prohibited lengthy chewing sprees and demanded downtime between sessions). To lubricate the process of chewing raw canvas, Sands ingested various liquids: a $4.50 bottle of shiraz he favours, called The Accomplice, produced the range of purple-hued stains; black tea with cow's milk produced the off-yellow stains; instant coffee with cow's milk, a colour almost indistinguishable from the tea stains; and water. From a distance, the traces of this chewing only subtly altere the viewer's eye by floaters in the vitreous humour. the otherwise completely white expanse of canvas. The faint, biomorphic-shaped stains appear to hover over its surface like an apparition, one perhaps even caused inside the viewer’s eye by floaters in the vitreous humour.

Like self-questioning one's eyesight, Sands' chewed painting forces a retreat inward. It engenders a multisensory and corporeal viewing paradigm that draws awareness across—and ultimately inside—the viewer's body. Close inspection of the canvas unveils its visceral and sculptural qualities. One hole reveals the picture hanging wire behind it, while the raised and frayed weave of the ten holes that wrap around the edges of the canvas disrupt the otherwise clean vertical and horizontal lines produced by its stretcher. Looking at the painting up close immediately enlivens aspects of the body, at first bringing one's attention to one's mouth, teeth and tongue via awareness of the protracted, non-nutritive chewing technique that has worn down the fibres of the canvas completely in some twenty-three places. This internalised, corporeal attention then travels from one's mouth to one's stomach. As is well known, the act of chewing prompts cells in the stomach lining to release digestive hydrochloric acid, which helps to break down food. Prolonged chewing in the absence of swallowing any food causes this acid to pool, where it begins to damage the lining of the digestive tract (the same health issue associated with chewing gum). Sands' chewed canvas registers here, in the pit of our stomach—the site of “strong emotions” and “visceral responses”.

In the sense that it draws on the digestive process in both the production and experience of the work, Sands' Untitled chewed canvas also extends a theme explored in an earlier untitled 2012–14 series of paintings. Sands made this suite of highly textured monochromes by mixing domestic rat poison with PVA glue and acrylic paint, then applying this pigment to a series of pictorial supports made of metal, wood and glass. If the digestive process of the Untitled chewed canvas is non-nutritive, that invoked by the Untitled rat-poison worksis specifically illness-inducing (or, indeed, fatal—if you are a rodent). Not entirely unrelated to Mike Parr's 1977 performative paintings The Emetics: Primary Vomit (I am Sick of Art), where the artist vomited up red, yellow and blue monochromes, Sands' rat-poison monochromes pivot on the imagined ingestion of a substance intended to destroy the body from the inside out. The ocular activity of appreciating a painting is again quickly displaced to the stomach.

As the Mouthal sculptures, rat-poison monochromes and Untitled chewed canvas all indicate, Sands' work draws clear parallels between the act of looking and consuming—but it refrains from celebrating this consumption as inherently healthy or life-affirming (in the sense that we all need to consume food regularly, like we need to breathe and sleep, in order to stay alive). Indeed, the spectral “body” that is conjured by Untitled chewed canvas is distinctly not in good shape. Texturally, it's pure body horror: its holes more like bumpy scars from badly healed stab wounds than the clean and clinical slashes of Fontana; its various pigments—oozing bodily fluids, infinitely more abject than Frankenthaler's soak-stains.

'”Looking” is & is not “eating” and also “being eaten”'—Sands' chewing process resonates with this oblique but nonetheless oft-cited quote from one of Jasper Johns' 1964 notebooks, which puts the ocular and the oral on a certain par. Sands worked on the canvas unstretched in his bedroom, chewing one bunched-up section at a time. While he could see parts of the canvas from this perspective, the area he was working on necessarily remained invisible to him—present instead through sensations of taste and touch, thereby deprivileging the eye as the master compositional tool of the painter.

The Johns quote applies to Sands' process to a degree, but falls short at the site of ingestion. For Sands does not “eat”-look, but rather “chew”-looks. To eat is to incorporate, absorb energy, or digest food matter in the stomach; to chew is to disaggregate, or break something down in the mouth. Innately entwined with the “existential condition of hunger”, the bite craves whereas the chew desires or savours, even while it de- and recomposes—and risks destroying—the object of its delectation. Metaphorically speaking, to chew is to mull a thought over, to resist making a snap decision, to spend time contemplating an event—or prolong its acceptance. The chew can be a kind of deferral strategy, as the opening paragraphs of Javier Marías' A Heart So White brutally remind us.

To return to the mouth as a technical support. The mouth is the uniquely privileged site of verbal communication, but it is also responsible, as Brandon LaBelle has argued, for a range of non-verbal communicative acts too: yawning, sighing, laughing, biting—the latter often associated with frustration over an incapacity to verbally communicate in the first place (hence its prevalence amongst pre-verbal toddlers). For LaBelle, the mouth—and its actions of biting, chewing, eating—”deliver the expressiveness of the body” (his emphasis); the mouth contributes to our “individuated embodiment” and registers “the extreme breadth of our vitality”. In calibrating what the body takes in and what it rejects, the mouth establishes the very boundaries of one's self—it is the most primal site of encounter with the world outside. Moreover—and this is where the thinking around Parr's Primary Vomit emanates from—the mouth and its actions of biting, chewing and eating are intimately connected to the site of the stomach, the innermost “core” of our being. For Parr, painting directly from the stomach via the mouth is a means of expelling everything that is peripheral and secondary in art to reach this pure, unmediated centre.

Sands' Untitled chewed canvas is forged in this highly charged and expressive cavity of the mouth, but it enacts both a refusal to speak and to ingest. Instead, the painting is the residue of a prolonged and ultimately non-transactional encounter. One that, both because and in spite of its negative expressivity, harbours acute affective dimensions—consuming the spectator.