Biennale of Australian Art

David Wlazlo

Lately I have been thinking about the growth and sizes of urban environments, the infrastructure required to sustain them as well as the potential limits on their growth. Can a city keep growing indefinitely and remain ‘liveable,’ whatever that means? Or is there some kind of limit—environmental, infrastructural, political—to the amount of people a city can sustain? What is the size of a city best suited to fulfilling the needs of its residents—water, food, air, etc? This broad line of thinking fits into questions of culture as well. To what point can the city’s myriad cultural events and festivals continue to grow? Is there a point where these officiated cultural events cease to enrich and serve only to distract? It is with these rather cynical thoughts in the back of my mind that I approached a recent addition to that most globalised of cultural categories, the inaugural Biennale of Australian Art (BOAA).

With over 150 artists spread out across Ballarat, BOAA certainly compares in scale to the large cultural festivals in Melbourne, but when placed in the context of a small regional city (albeit Victoria’s third largest), the effect is amplified and contrasts quite sharply with the day to day of a non-capital Australian city. Missing the usual and often over-stretched curatorial justifications for such Biennales, Artistic Director Julie Collins’ aim was simply to present a wide array of Australian art within the village-like environment of Ballarat. This environment, she observed, would provide a perfect place for a large exhibition that reflects the diversity of Australian art, as well as the complexity and intersectionality that a term like ‘Australian’ can mean today. Collins’ skill, I think, was in realising that this layering and complexity is already active within Ballarat the city: the continuing strength of the Wathaurung, the history of immigration and globalisation from the gold rush in the mid-nineteenth century, the environmental destruction enacted in the search for capital; all of these factors are present and drawn on within the Biennale. Ballarat as a location also speaks to the links between national pride and nationalism through the Eureka Stockade museum—part of BOAA—and a nearby disused Bacon factory provides a very dilapidated and half-condemned corrective to the standard white cube of contemporary art. Other sites across the city are St Andrews Church and over thirty outdoor sculptures presented around Lake Wendouree.

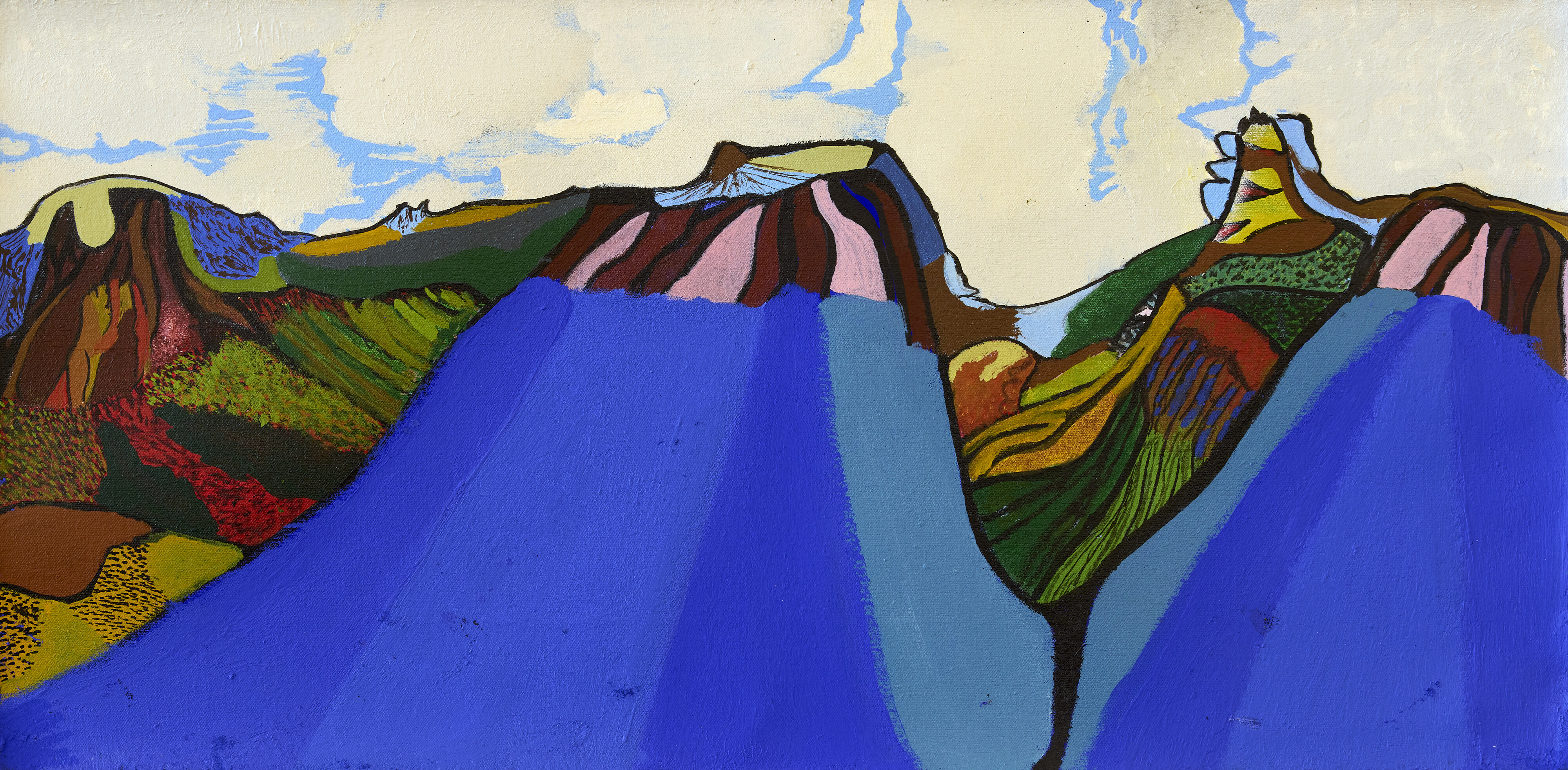

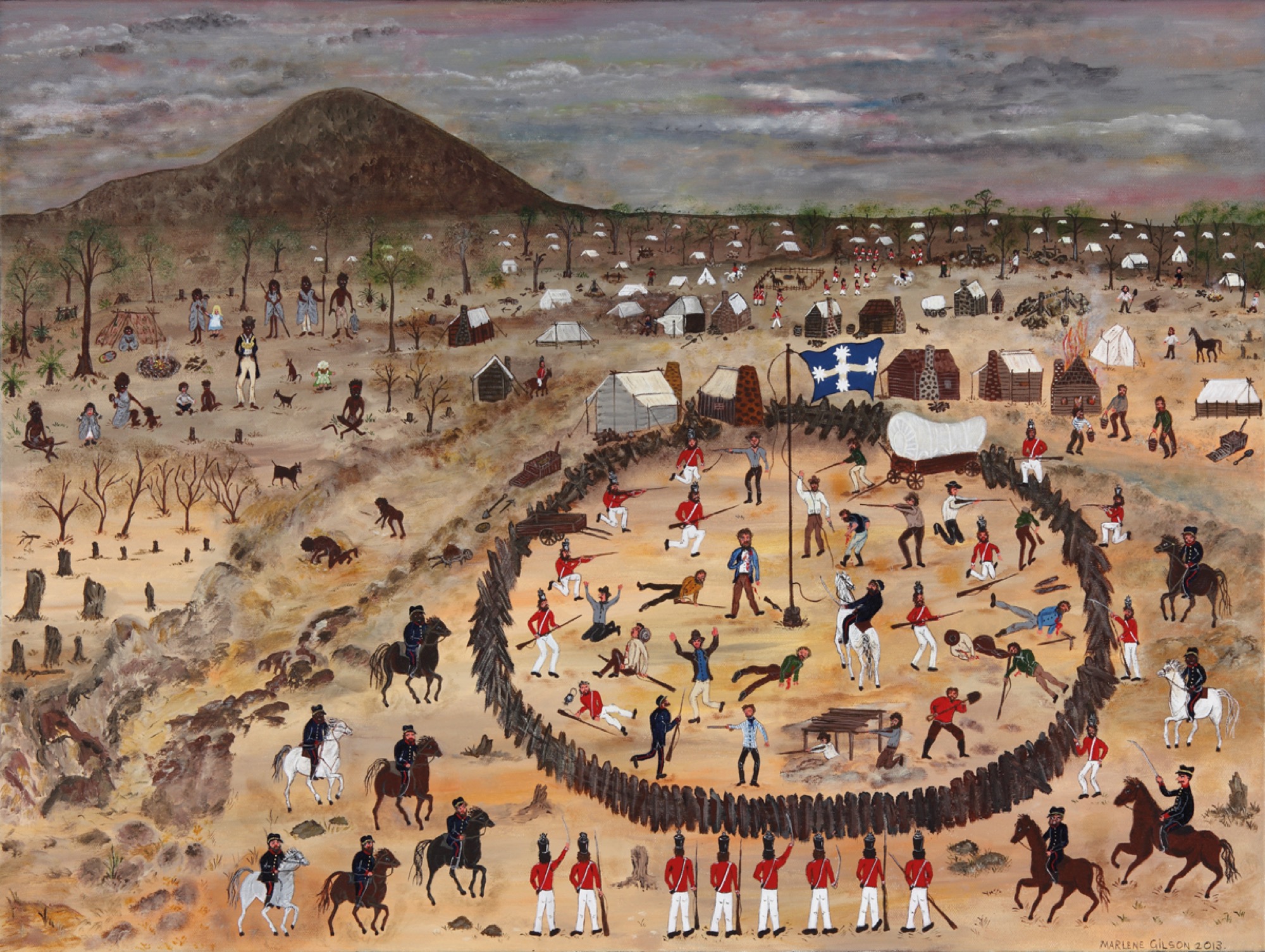

Centred around and within the Art Gallery of Ballarat, a cluster of exhibitions and works vary between more traditional media and contemporary installation. Within the gallery, Marlene Gilson’s historical paintings of early Wathaurung/settler interactions recast local history and history-painting, while downstairs the sherbet rainbow installation of Pip & Pop sits joyfully hyperactive next to the atmospheric and evocative installations of Asher Bilu. Close by, Lisa Anderson’s large installation of allegorical polar bears in the Trades Hall sets off a series of mechanised chittering teddy bears in a frenzied reflection on climate change. Around the corner, Heidi Wood’s hand-painted wall graphics are like condensed icons, drawn from zones of architectural detritus in the former Soviet bloc.

Sometimes I get the feeling that an exhibition organiser is trying to lead me somewhere, to suggest and influence at a distance, through the artworks. It’s often an uncomfortable experience, and BOAA seems to avoid it. The relaxed curatorial framework enables these works to speak for themselves in a way not often seen in such large exhibitions. Artists and works retain diverse material approaches and genres across BOAA’s many disparate locations and buildings.There is the decommissioned church of St Andrews housing a collection of eight-metre landscapes in various media, while the church hall contains quite a mix of installations and more traditional media, such as Karyn Fearnside’s ethereal muslin masks illuminated under ultra-violet light and the Burlesque invitation to dance of Erin McCuskey’s City of Luxville. The church location seems to be downplayed, as though it is just another venue on the transition to development and gentrification—it was recently sold pending planning permits—but I can’t help thinking of the more controversial St Patrick’s cathedral opposite, where a silent protest against child sexual abuse in the Catholic church has been going on for some years in the form of colourful ribbons tied to the iron fence. St Andrews provides an interesting and rich temporary gallery, but it is certainly not simply another building. I can’t help feeling that here a little more curatorial direction might have explored this sadness more vividly, but then again perhaps some things are too raw to be submitted to the rather public and often performative explorations of trauma enacted in art exhibitions. These things are still going through the judicial system.

Another site with the potential for politicisation is the Eureka Stockade museum, which hosts some five works in BOAA. Alongside the ideological reassurances of the museum’s main attraction—the original southern cross flag from the Eureka rebellion of 1854 is presented as a relic within—a number of works explore the valuation of gold, value and working-class labour. Ken and Julia Yonetani’s The Golden Pyramid threads 24 carat gold thread into a pyramid within a darkened room, a reflection on the fascination with the precious metal across cultural boundaries. It is a seemingly formal exploration of material and shape, but in the context of the Eureka Stockade, the political and social power of form and matter is palpable. Jane Skeer’s True Blue is a hanging group of trucker’s ratchet straps in varying blue hues, presenting a curtain of webbing in a small room again testifying to the way that form can be political or even ideological.

The George Farmer building, an old meat curing factory, is perhaps the most consistently engaging venue. The dilapidated building smells of mildew in the dark and low-ceilinged basement, where Ryan F. Kennedy’s performance and installation SAPIENS explores ideas of human technology and myth. It is a visceral, bloody and rather disturbing work that often gets close to a kind of sublime ridiculousness through the tropes of horror available in the smelly, dark basement of a disused bacon factory. Jason Waterhouse’s Automotive Geologies is in a nearby room, with its glossy forms emerging out of the floor like gelatinous growths, and Gordon Monro’s frenetic video installation Bubble Chamber is like the server room of the internet hive mind’s unconscious. Upstairs, the dual-channel video projection by Abdul-Rahman Abdullah boxing his brother is projected on a flaking wall, and nearby are the performance and photographs of Jill Orr’s Detritus Springs, wherein the artist portrays a kind of post-apocalyptic medicine woman ushering in the new growth of weeds and plant life through the cracks of the building. In this familiar setting for contemporary art (the post-industrial condemned building is a kind of trope of site-specificity), there are many many works, too many to account for and describe.

The Ballarat Welcome Centre is a cross-over between the disused and sacred, housed in an old convent. Upstairs the paintings of Matjangka (Nyukana) Norris are a highlight, and downstairs Louise Paramor’s Divine Assembly, a series of free-standing sculptural forms, is amazing in its occupation of the former chapel. The plastic constructions occupy the theatrical space of the church very much like ritual human figures or some kind of liturgical Tupperware. Paramor’s work is so effective in this space that in comparison the other works—which for the most part do not really engage with the rich institutional history of the site—seem to become inward looking.

For the most part, I went to BOAA already convinced that a large recurring exhibition in a more regional city of Australia was a necessary corrective to the spectacular ‘bread and circuses’ of White Night, Melbourne Now, the NGV Triennial et al. BOAA delivers on this through its ambition and scope, its capacity to change the experience of the smaller city, and the relatively relaxed curation. In future iterations, it would be good to see more balance between this light touch of the curatorial team and more in-depth and critical reflections on the sites that Ballarat offers. However, far from the stage-managed and well-funded festivals presented in larger cities, BOAA feels more real, a bit rough round the edges, and—as a festival—seems more likely to have a lasting effect through its broad emphasis on art, music, children’s activities, lectures and screenings. I can only hope that unlike the single-use Melbourne Biennial of 1999 (never heard from again), that BOAA secures ongoing support and continues the sequence it promises.

David Wlazlo is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.