Arlo Mountford: Deep Revolt

Sophie Knezic

One hundred years ago, in a mood of revolutionary zeal, Kasimir Malevich proclaimed Russia the centre of political life, “the breast against which the entire power of the old-established states smashes itself”. The sentiment appeared in his polemic, 'On the Museum' (1919), a paean to the transformation of contemporary life, offset by a denouncement of the museum as a retrograde cultural institution filled with “dead baggage – the depraved cupids of the former debauched houses of Rubens and the Greeks”. Notwithstanding the summoning of an improbable mammary metaphor, an association between museums and their historically necessary annihilation was set.

In terms only marginally more restrained, the repugnantly bourgeois nature of the museum had already been professed by the 19th-century Russian Cosmism philosopher Nikolai Fedorov when he wrote, “The only thing higher than the old tatters preserved in museums is the very dust itself, the very remains of the dead; just as the only thing that would be higher than a museum would be a grave…”

Arlo Mountford's suite of digital animations, made between 2005 and 2018 and currently on show at Shepparton Art Museum in the survey exhibition, Arlo Mountford: Deep Revolt, appears to align itself with this revolutionary appraisal of the museum as a sepulchral place tinged with the malodorous fumes of death. Collectively, Mountford's works reveal an obsession with museums as subject matter – four of the seven animations featured in the survey are set within a museum environment – but figured as accursed locations, best wantonly destroyed.

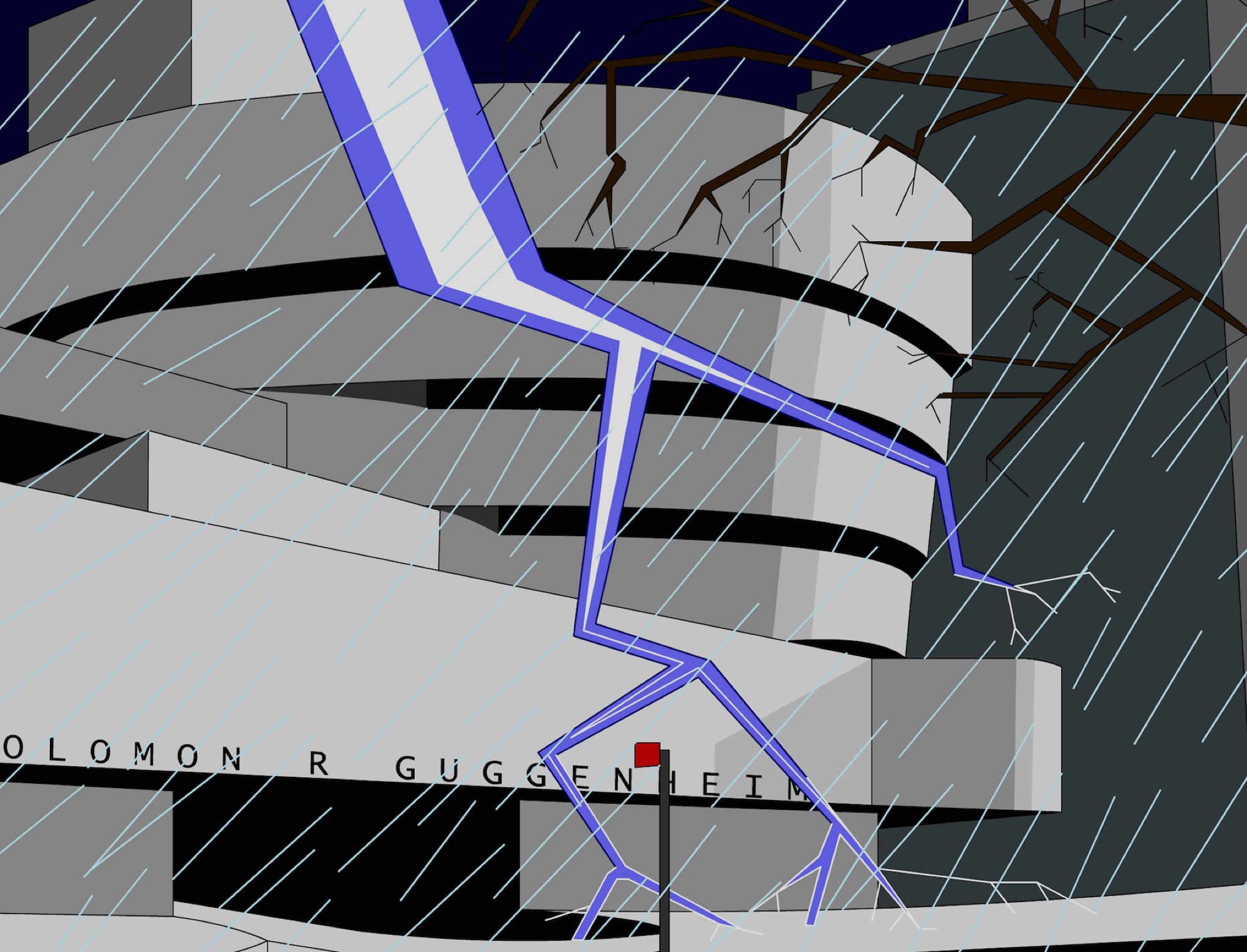

An early work, Murder in the Museum (2005), positions the museum as a locus of sadistic terror. Opening with an ominous shot of the façade of the New York Guggenheim illuminated by flashes of thunder and lightning, the 4-minute animation reworks the genre of the slasher film (specifically Friday the 13th Part Two), by re-siting it in a collaged mash-up of archetypal art museums such as the Tate Modern and MoMA. One by one, the characters are picked off by a merciless killer – including an unfortunate couple slaughtered mid-coitus – in a spoof of genre cinema that gleefully straddles horror and humour.

While Murder in the Museum casts the museum as the sinister backdrop for diabolical acts, Galaxy Express NMWA (2014) glorifies in its hyperbolic annihilation. The work similarly mashes actual museums with cinematic prototypes, taking its title and narrative arc from Rintaro's anime film Galaxy Express 999 (1979) – based on Leiji Matsumoto's manga of the same name – re-edited and re-released by Roger Corman the following year. Mountford's adaptation takes place in a 3D rendering of the New Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, commencing with photographic stills that gradually morph into anime-style animation. Ignited by a firebomb, the combusting museum shudders and splinters in almost orgiastic heavings of disintegration.

The building's spectacular collapse conjures experimental film and contemporary art antecedents: Michael Snow's structuralist film Presents (1981) with its memorable sundering of cinematic realism through the auto-destruction of the film set and props, the camera itself becoming a battering ram; and Jeff Wall's The Destroyed Room (1978), whose scene of wreckage in turn remakes an iconic art-historical precedent – Eugène Delacroix's The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), with its own extravagantly frenzied imaging of ruination.

Galaxy Express NMWA seems to corroborate the observation made in the heyday of '80s appropriationism by Postmodernism's quintessential theorist, Douglas Crimp, that “we are not in search of sources or origins, but of structures of signification: underneath each picture there is always another picture”.

The axiom, however, is histrionically literalised in the exhibition's centrepiece, The Triumph (2010) – a mise-en-abyme of art-historical quotation. In a tone more sombre and elegiac than any other work, this animation overflows with a relentless cascade of modernist art references. The setting of the museum is eschewed in favour of a rustic landscape scene that replicates the composition of Peter Bruegel's The Triumph of Death (1562). Mountford takes the painting's desolate envisioning of massacre into even more nightmarish territory. The dusky rust-coloured land and sky convey a sense of portent, overlaid with a plaintive rendition of Ol' Man River that accentuates the air of lament. Mountford turns Bruegel's scene into a vision of hell overrun with the kinds of famous artworks usually housed in prestigious museum collections. Perhaps the museum is present after all; the broken tower in Bruegel's original composition is now a Brutalist building façade, looking suspiciously like Roy Grounds' NGV.

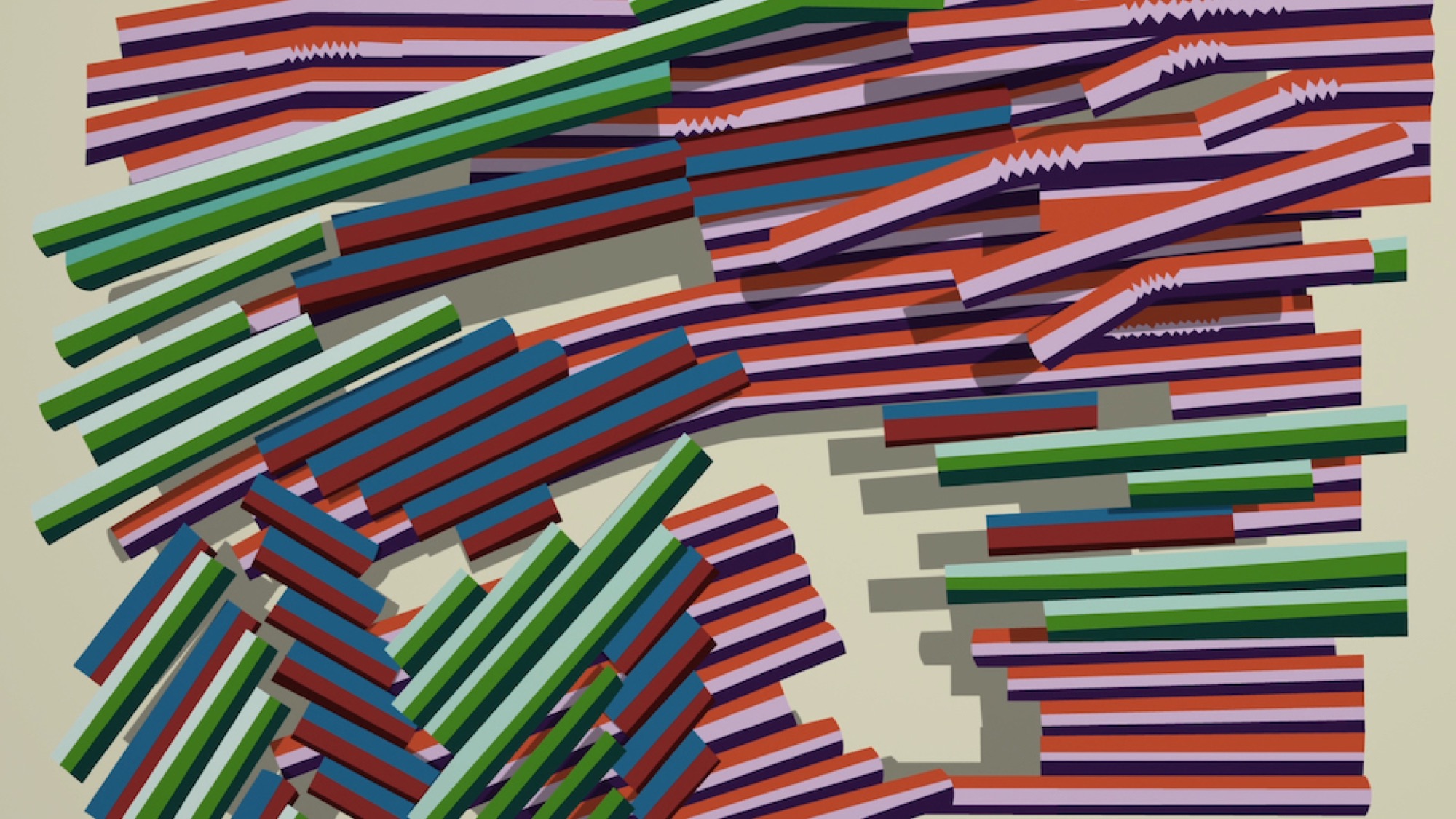

A cavalry of horsemen race across the landscape holding banners aloft, emblazoned with iconic works – Edvard Munch's The Scream (1893), Meret Oppenheim's Le déjeuner en fourrure, (1936), Kasimir Malevich's Suprematist Composition (1916). I can barely keep up – the barrage continues with Magritte's Ceci n'est pas une pipe (1928-29) and Picasso's Desmoiselles d'Avignon, (1907). Elsewhere in the sequence, a figure traces Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty (1970), another cycles into a lake in cartoon replication of Bas Jan Ader's The Fall II (1970) and the Guerrilla Girls pop up and disappear off-screen. An inverted corpse is dragged unceremoniously across the landscape, trailing a line of blood coloured in Yves Klein Blue. Soon after, death marchers traipse across the hilly landscape carrying placards studded with more canonical 20th-century works: Warhol's Brillo Boxes (1964), Bridget Riley's Blaze Study (1962) and Barbara Kruger's I Shop Therefore I Am (1990).

Both Breugel and Mountford's tableaux stage battle between the living and the dead in the form of fleeing humans and skeletal grim reapers, but the mounting carnage – corpses strewn across the ground like the All Deaths scene in Westworld (2016) or a zoom into the Chapman Brothers' Fucking Hell (2008) – testifies to death as the ultimate conqueror. What distinguishes Mountford's version is the transformation of the landscape into a terminus for world museums' epochal artworks, funnelled into the apocalyptic scene.

In the early 1970s, Daniel Buren would continue the censure of the museum, disparaging its embalming operations of collection and preservation, its craven function of refuge. The Triumph perversely inverts Buren's critique through envisioning art's refuge as not within the pristine walls of a museum but in open terrain, exposed to gruesome, carnal scenes of disaster. But where, we might ask, is the refuge in images of such calamity?

In her analysis of sci-fi disaster films, Susan Sontag viewed their aesthetics of destruction as masking the deepest anxieties about contemporary existence. Such films gloried in the spectre of apocalypse as an emblem of humans' incapacity to properly assimilate terror. Images of disaster displaced into filmic fantasy served the function of immunising the individual from that which is psychically unbearable. So when Mountford speaks of the necessary slaughter of his plotlines and characters, stating “I'm often killing off older artists”, we might initially interpret this as baring an Oedipal death drive towards the unendurable weight of art-historical precedent.

But is it not significant that most of Mountford's works are framed by reference to museums above and beyond artworks per se? Rather than a somewhat predictable imperative to despatch artistic precursors, what remains foregrounded in Mountford's animated world is the implacable presence of the museum. Even his trademark figure, a unisex cipher, based on the early 20th- century isotype – a graphic system for translating statistical information into comprehensible data pioneered by the science philosopher Otto Neurath – was developed in a museum setting: the Gesellschafts und Wirtschaftsmuseum (Museum of Society and Economy) in Vienna in the 1920s.

In Mountford's universe, visions of museological disaster might then be understood as immunising against a cultural fear, not of the museum's annihilation but of its indestructibility. Deep Revolt would not then be a revolt against the museum itself, an affiliation with the lineage of institutional critique, but an insurrection against its very inability to be extirpated: the museum as the horror of a Nietzschean eternal return of ineradicability.

In his re-reading of Malevich’s revolutionary pronouncements, Boris Groys viewed the Russian artist as framing the history of modern art up to the moment of Suprematism as the progressive destruction of art's figurative traditions: the by now familiar refrain of successive obliteration. But in asking what could survive this permanent work of destruction, Groys attributed Malevich with the answer – “the image that survives the work of destruction is the image of destruction”. In other words, the seemingly endless cycles of annihilation only underscore the fact that revolutionary fervour and willful iconoclasm cannot destroy its own image. Arlo Mountford gives us that image.

Sophie Knezic is a Melbourne-based writer, academic and visual artist who works between practice and theory. She currently lectures in Critical and Theoretical Studies at the Victorian College of the Arts, The University of Melbourne and in History + Theory + Cultures at the School of Art, RMIT University.