Andrew Browne: Spill

Paris Lettau

In the final chapter of his 1931 book, An Account of French Painting, Clive Bell attempts to explain what he calls 19th century French painting's (i.e., modernism's) 'momentous lapse in taste'. Of course, he meant a lapse from the perspective of those trained in the 19th century Academy's tradition of taste, and all the standards of painting it sought to uphold. For Bell's generation, on the contrary, the late 19th century was seen as a new beginning for painting: whereas previous generations had followed tradition and imitated the masters of the Academy, Bell said, modernists sought an original genius, to break from institutional embeddedness, to present a pastiche of all that was on offer; a new synthesis of any style, genre and technique, symbolised by that eclectic tableau, The Luncheon on the Grass, by Édouard Manet, famously rejected by the jury of the 1863 Paris Salon.

But if the 19th century produced modern masters, Bell argued it also produced more bad art than any other century. For by imitating the masters of the Academy, an otherwise peripheral painter was at least capable of being acceptable. Only when the work of an original genius, having confused all the examples of the old masters, comes impure before the public is it recognised for what it is—something profoundly disquieting.

To call Andrew Browne's practice 'disquieting' would, of course, be to say nothing new. In fact, a scan of the literature on his work shows that this, in some register or another, is about the only consistent thing said about his gothic greyscale drawing, painting and photography: it is disquieting, filled with suspense, dream-like, humming with mystery, with a sense of desolation, an uneasy mood of chaos and unpredictability, an anthropomorphic and menacing romance.

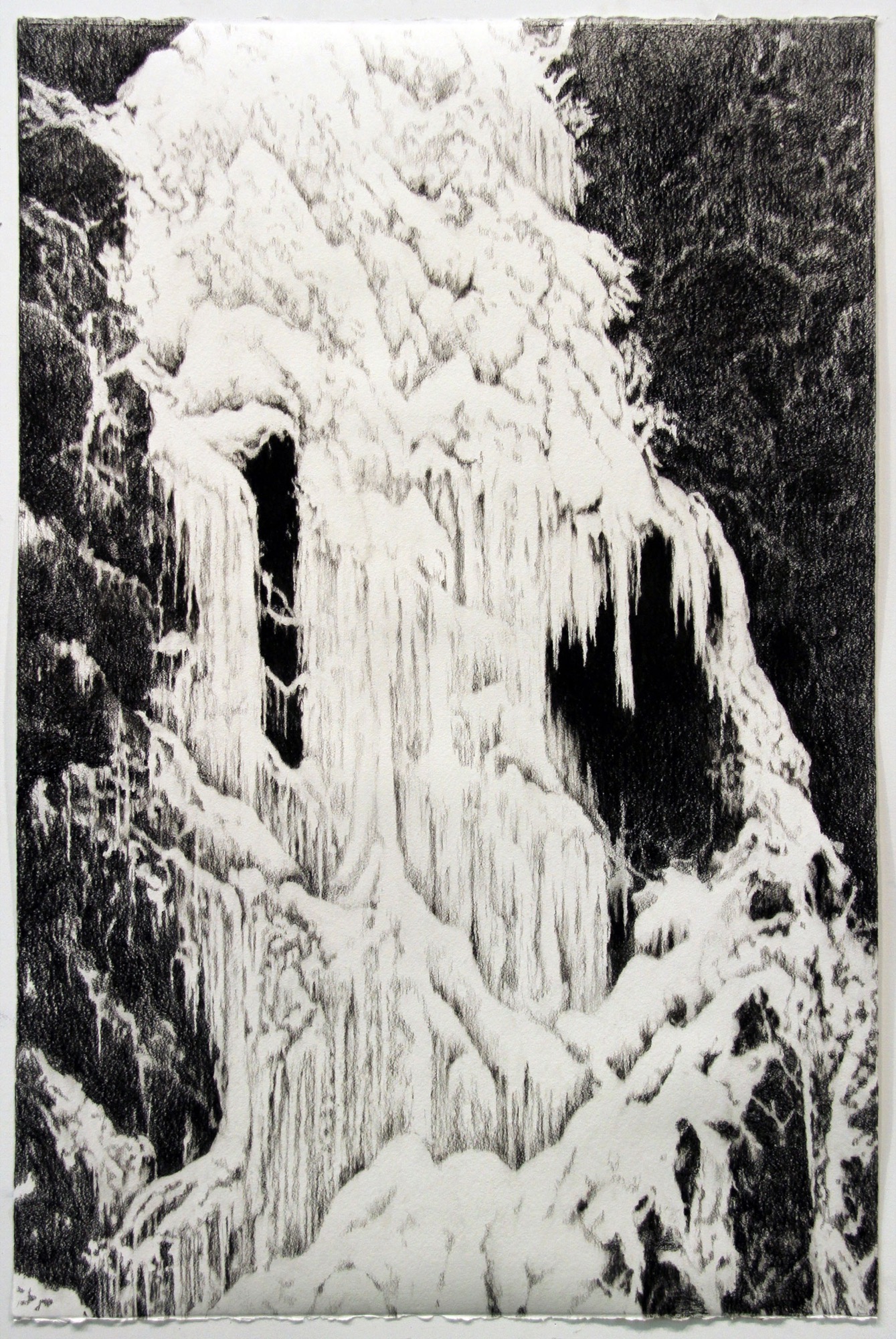

These could all be obvious claims of the works in Browne's current show, Spill. The first five framed charcoal on paper works, for instance, all display this sense of disquietude: a fawnish romanticism that's deliberately fantastical. Frozen, for example, shows a glacial flow of water arrested in charcoal, recalling in black and white the eerie and fantastical atmosphere of William Blake's 19th century illustrations to John Milton's Paradise Lost. At the same time, though, there's something altogether mundane about these works, as if their disquietude were just an afterthought or an after-effect, a result of Photoshop editing: in Drawing (above left), for example, it looks as if a black and white photograph has been digitally inverted to produce the effect of a photographic negative and a hand-drawn 'vibe'.

This is not to say the works are a gimmick, but that the uncanniness of the images seems somehow artificial, almost beside the point, in the same way that the subject matter of a post-impressionist painting—take for example the nude in Emmanuel Phillip Fox's Summer (circa 1912)—is a neutral foil for the artist's intended study of light, colour, texture and atmosphere; or if not a neutral foil, then a conflicted artistic intent in which a formal study fights a 'mysterious' effect, and vice-versa.

This doubling of half-intents reads almost as a confusion of style, as if Browne's work half accidently, half deliberately, acts against itself and undermines its own elements. It is in this rather roundabout sense that there is something disquieting about Browne's work; not disquieting in the sense of the uncanny, but in the sense meant by Bell: that it seems to escape the properties an academically trained taste is brought up to identify and admire, as if the works were judging taste itself. In a similar way, that is, that the jury of the Paris Salon was disquieted by, and so sought to ban from public view, Manet's Luncheon: a painting that combined elements of genres that were supposed to be hierarchically separated.

A similar point can be made about Descent, a large oil on linen in which the compositional logic of 'downwardness' is heightened by scale—as well as by artificiality. This downwardness forms part of the show's premise, and is derived from its title Spill, an abstraction from the idea of falling water, which is itself an abstraction from photographs of waterfalls taken by the artist. The work is partly reminiscent of Gerhard Richter's abstracts and photo paintings, such as the blurred Uncle Rudi, 1965, or his well-known overpainted photographs. But Descent lacks that naturalised Richter-esque synthetic tension between photograph and paint seen in the overpainted photographs, for example—that unified pressure of material paint against the ideality of the photograph; an ideality that, in turn, both holds onto the paint and renders it irreal and weightless. Unlike Richter's photographic surface, in Descent the black primed linen does not synthesise with its overlayed paint into a resolved compositional tension. Each layer floats passively up against the other. Even fateful splatters of paint abolish their sense of chance, in that each one feels half intended, artificial, placed. The surface is slippery like a perimeter fence, unwelcome to the paint that descends its surface.

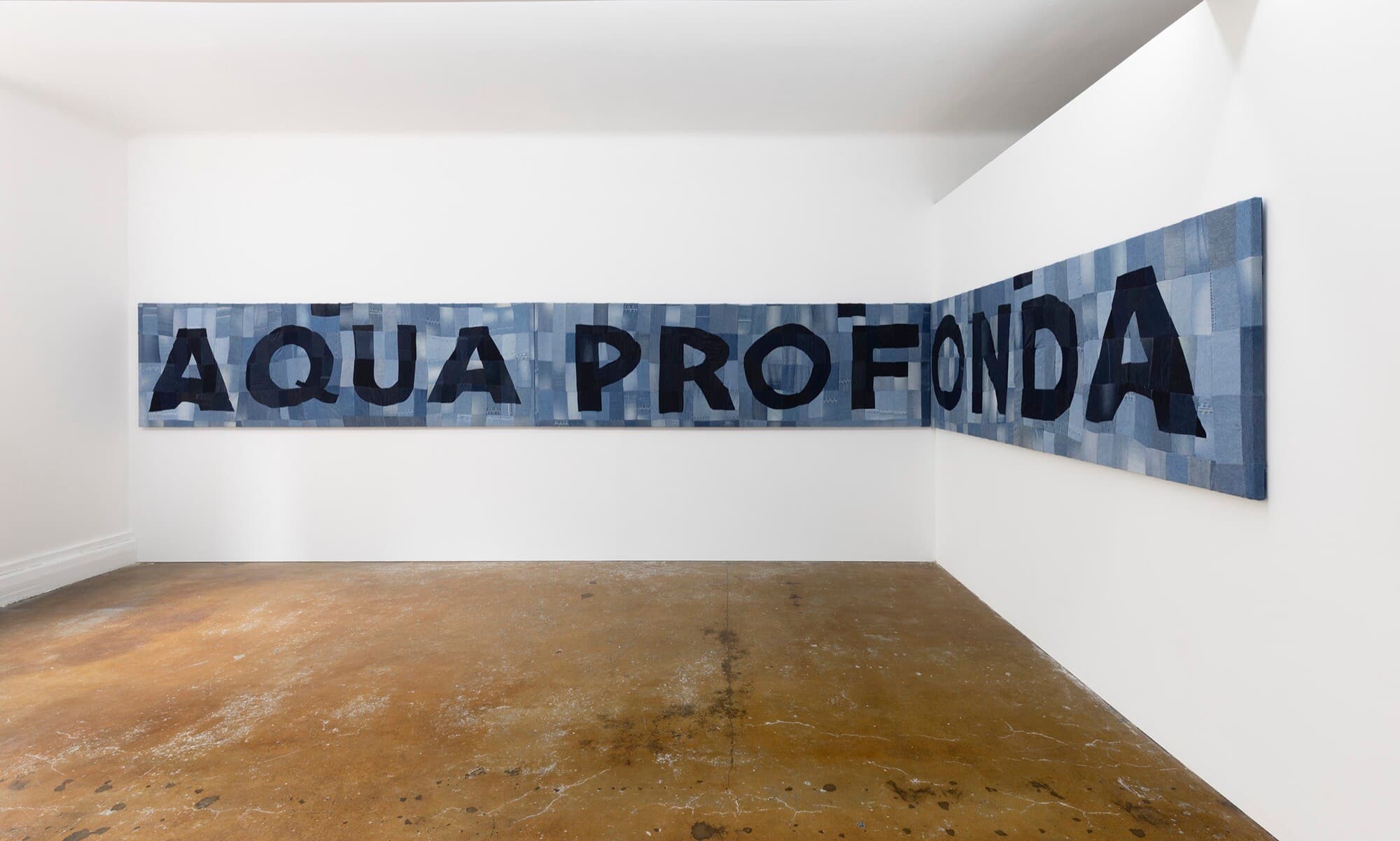

One work in Spill is offered by Tolarno as if it aspired to the virtual heights of the prized genres of 19th century Academic painting. According to Tolarno's website, Threshold measures an immense 150 x 605 cm, thus presenting itself in the grand tradition of history painting, like Benjamin Duterrau's enormous and now lost A National Picture, 1840, currently being projected onto the walls of the National Gallery of Australia, or Gustav Courbet's gigantic A Burial At Ornans, 1849-50 (that great metaphor for the burial of the Academy's hierarchy of genres). The huge scale of Threshold thus far eclipses the dimensions of the wall it hangs on, which must be less than 500 cm. If the dimensions are an obvious typo (one reproduced across the internet), it is a particularly interesting one. Not only does it suggest an extraordinary scale of ambition on the part of the artist, it also suggests an immense, if virtual, breadth of genres and styles across work presented in Spill.

In fact, Threshold also recalls Sydney Long's symbolist art nouveau (yet another 'style') arcadias, such as Pan, 1898 (close to Threshold's actual, rather than mistyped dimensions), populated as it is with nymphs and satyrs. If Browne, like Long, alienates the landscape of the picturesque, Long's transferal of the melancholic onto the Australian landscape is missing in Browne. In fact, Threshold lacks all signs of place to truly be described as Australian gothic abstraction; its utopic, cartoonish netherworld, is populated instead by a shadowy, ambiguous urban Pan standing on a horizontally aligned turnip-like earth.

The flattest of all the works—and smallest—Silver Spill, breaks with the idealised downward direction (i.e., the idea of the 'spill' of water) of the show to present a far more even, uniform modernist space. The layering of swathed brush strokes on black primed linen recalls Francis Bacon's 1953 Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X, except it lacks that sense of a frightful breakout into the abyssal nothing of the painterly ground. In Silver Spill, everything floats forward, once again, in a virtual rather than existential (or even ontological) space.

The verticality of the picture support, hung like a portrait, follows that of most the works in the show, only it doesn't use the downward movement of falling water to derive its compositional logic. In Silver Spill, the light silver-ish foreground 'spill' falls up as much as down. The middle-ground swathed brush strokes make the same double move up and down, from a stroke beginning in the lower right corner and lifted upward, to another beginning in the upper right corner and pulled down. Downwardness is also thwarted by the central 'opening' of the foreground silver spill, which anchors and centres the picture, but which is also unbalanced by a second opening slightly above it—and each framing a few splatters of paint as if, like the impressionists, the artist sought to capture a fleeting moment of chance, to harden and abolish accident.

Browne half-deliberately hovers in this virtual space between impure mixture and original synthesis in a way that makes his work especially, if obliquly, interesting, like Manet’s new proposition of what a successful tableau could be. This is what is so disquieting but also compelling about Browne's practice—even its paradox—that it ultimately appears, like Manet did in the 19th century, as an eclectic yet persuasive pastiche, in which each stylistic effect counter-poses against its other: melancholy symbolism with post-impressionist study of light, colour, texture and atmosphere; modernist space with romantic uncanniness; history painting with Baconian chaos and disintegration; Richter-esque synthesis of painting and photography, but without synthesis. A cogent practice of pastiche hidden beneath a thick veneer of gothic greyscale.

Paris Lettau is writer from Melbourne.

Title image: Andrew Browne, Silver spill 2018, Oil on linen, 61 x 41cm, courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries.)