Alex Hobba, A Gun Went Off in Human Resources; Alex Cuffe, Love is the Length of Her Hair

Chelsea Hopper

The attention-seeking coronavirus, having made it physically impossible to see art exhibitions, has also emphasised a distanced way of seeing. I can look at an exhibition without having to touch anything or talk to anyone or go anywhere. I can just sit here, somewhat isolated and alone (I live Southside), staring at my computer screen, tapping my keyboard, clicking my mouse. Both exhibitions by Alex Hobba and Alex Cuffe at TCB have been on display since March, suspended in time like a pregnant pause. Although the exhibitions were open to visit for a brief moment, around two or three days in July, the second wave of Melbourne’s lockdown forced the gallery to suddenly close until further notice. The installation shots of each exhibition space, collated into online catalogues, have come as their own versions of the shows, complicating what we can devote our attention to.

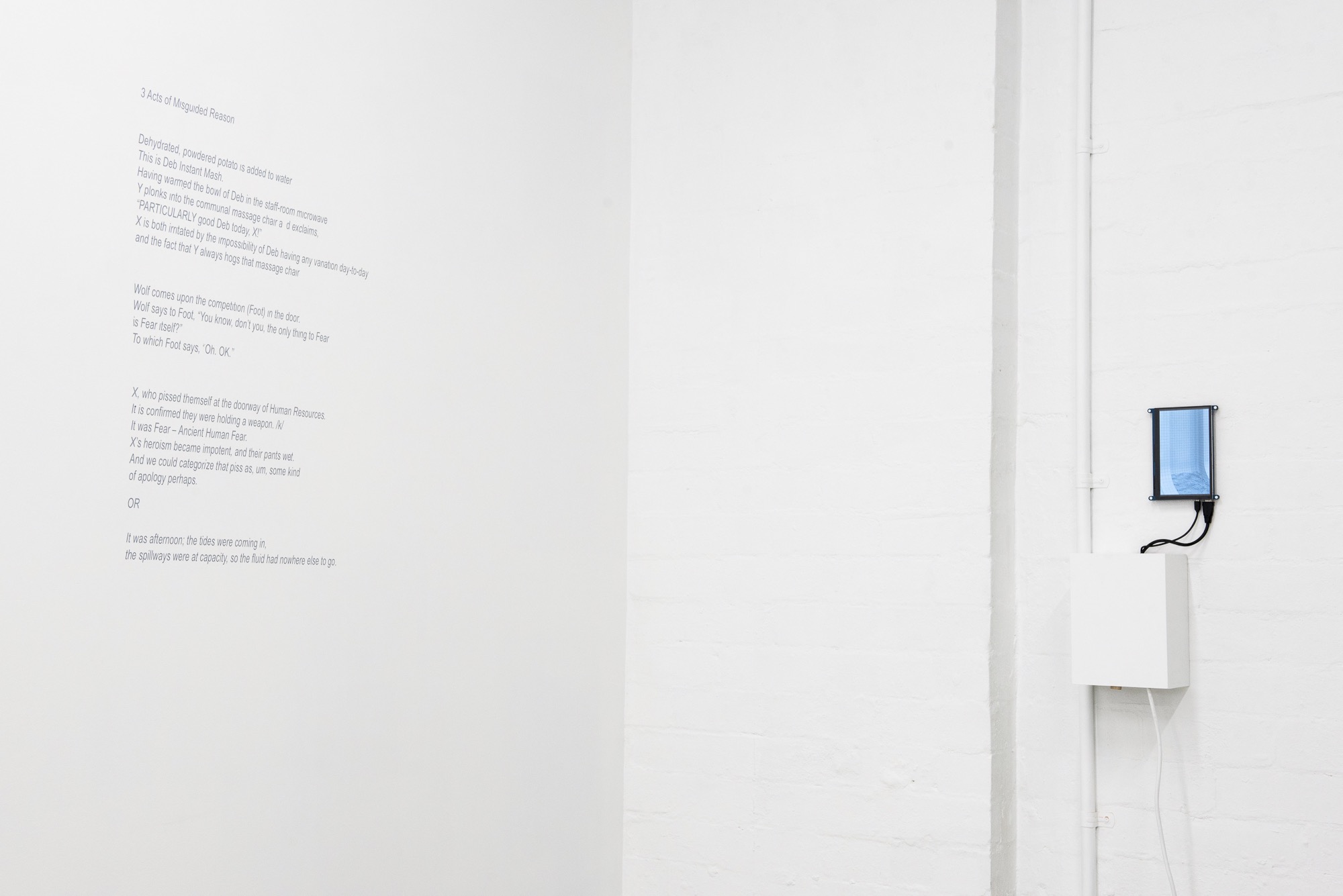

In Alex Hobba’s exhibition, titled A Gun Went Off In Human Resources, attention pivots around a central narrative, a linguistic framework detailed in the vinyl decal printed on the gallery wall, subtitled “3 Acts of Misguided Reason”. The narrative described in these three “acts” becomes the glue binding together the somewhat uninviting, slick and sterile looking forms that are scattered across the gallery space. At first glance at the exhibition’s documentation, it is not explicitly apparent how the “3 Acts” are illustrated. These visual prompts—a large cartoonish drawing, plaster casts, 3D computer rendered images and looped videos playing on tiny screens—aren’t set out as cryptic. Instead, they act as small invitations to read into a humorous tale.

The first “act” detailed in the black vinyl wall text is an imagined office situation, the prelude (or fuel) for a fictional character, known as “X”, to rationalise their own endgame of committing homicide in the workplace for trivial reasons. We’ve all been X. Haven’t we? We repress our deep disdain and irascibility watching the daily horror of the many abject-looking microwaved lunches waft over and into every surface of an office space (including your own body, psyche and lunch). Or we witness the lack of spatial awareness co-workers are more than capable of, as they colonise parts of the staff room with bake sales no one asked for or loudly clang their spoons like childish musical instruments during morning tea, while scraping the remnants of their homemade yogurt from the corners of a large glass Tupperware container. For Hobba, the two culprits are a character called Deb and another named “Y”. As Deb prepares her instant mash in the microwave for lunch, Y hogs the communal massage chair. Near one of the doorways at TCB, fixed beneath a large pane of glass, Y Hogs the Massage Chair (2020), a 3D computer rendered drawing of the leg cushions from a white expensive looking electronic massage chair acts as an abstracted visual cue for this fictionalised narrative. Although we never see a depiction of Deb or smell her lunch, Hobba gives us more than enough substance through our own introspective associations to sympathise and ally with X’s circumstances behind “going postal”.

Hobba’s fictional situation continues to play out in the wall text describing the third “act” wherein the character X pisses themselves at the doorway of Human Resources while holding a weapon. Although the title of Hobba’s exhibition indicates that the weapon (a gun) “went off”, in this imagined narrative X is unsuccessful. As X is struck by fear (“Ancient Human Fear”, as Hobba emphasises), the fight or flight mechanism “triggers” X’s bladder to relax and expel urine. X pisses themself and fails to kill anyone. Assuming, of course, that X has a penis, perhaps the “gun” is not the mechanical device but a metaphor for something more corporeal that manages to create a memorable event but one of embarrassment—warm, wet and powerless. Or was it simply an accident? Hobba describes the piss as “some kind of apology perhaps”. I’d like to think it was an accident.

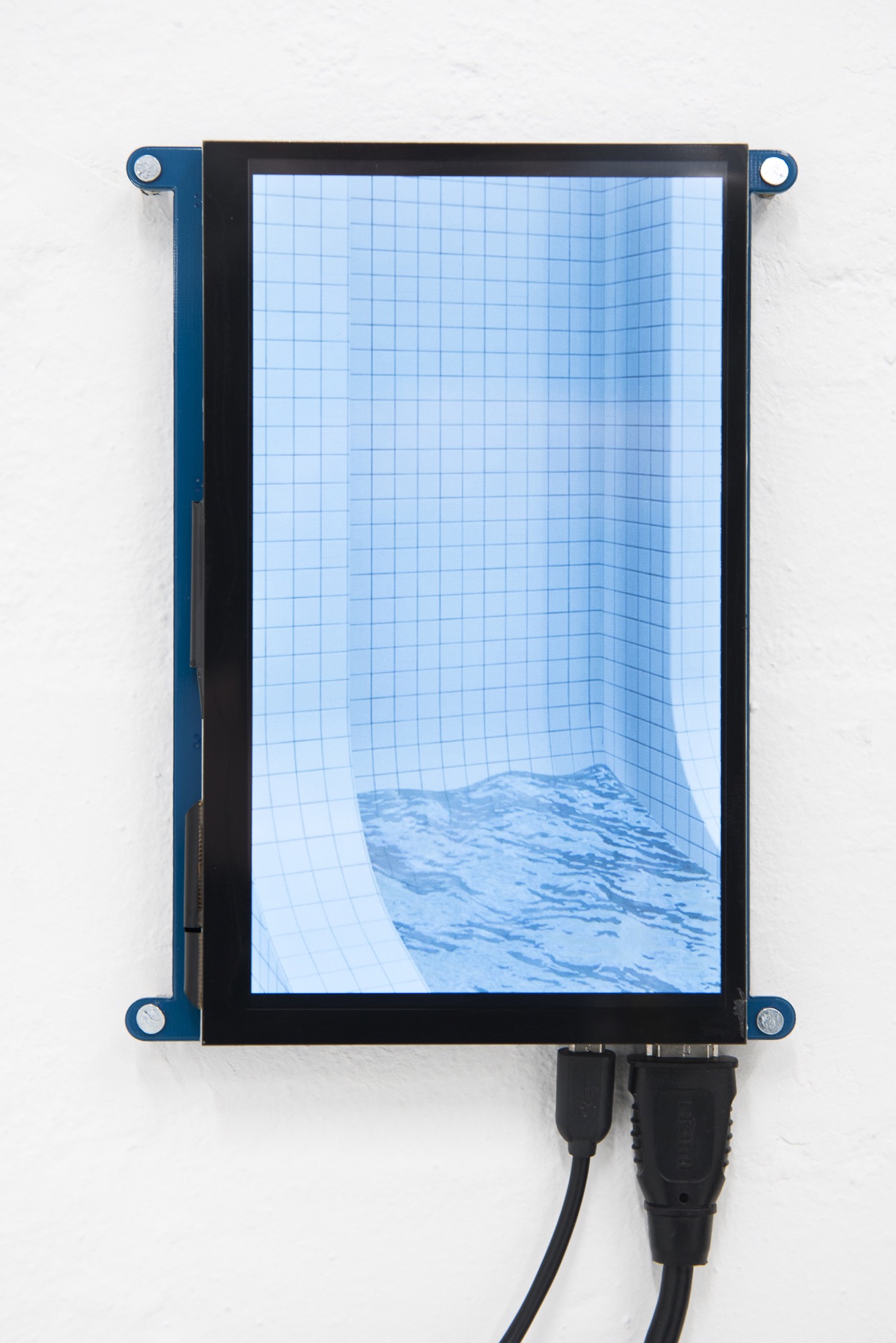

The alternative to this act, which is also manifested in further visual abstractions, is modelled and designed in looped videos of X’s failure to kill. The urine is lyrically animating as “spillways” that have “nowhere else to go”. These “spillways” of piss (although colourless, clear “healthy” pee) act as a kind of liquid failure both appearing (or alluded to) in two 3D computer rendered simulations arbitrarily playing on repeat: Piss Trough Spillway (2020), a urinal filled with piss constantly in motion, and Exit wound (escalator) (2020), in which two escalators hypnotically operate and are never quite engulfed by a thick white mass surrounding them. Maybe these escalators lead up to Human Resources and the cloud-like mass doesn’t even signify piss at all but suggests or symbolises how precarious one can perpetually feel in a workplace—silent, unappreciated, overwhelmed.

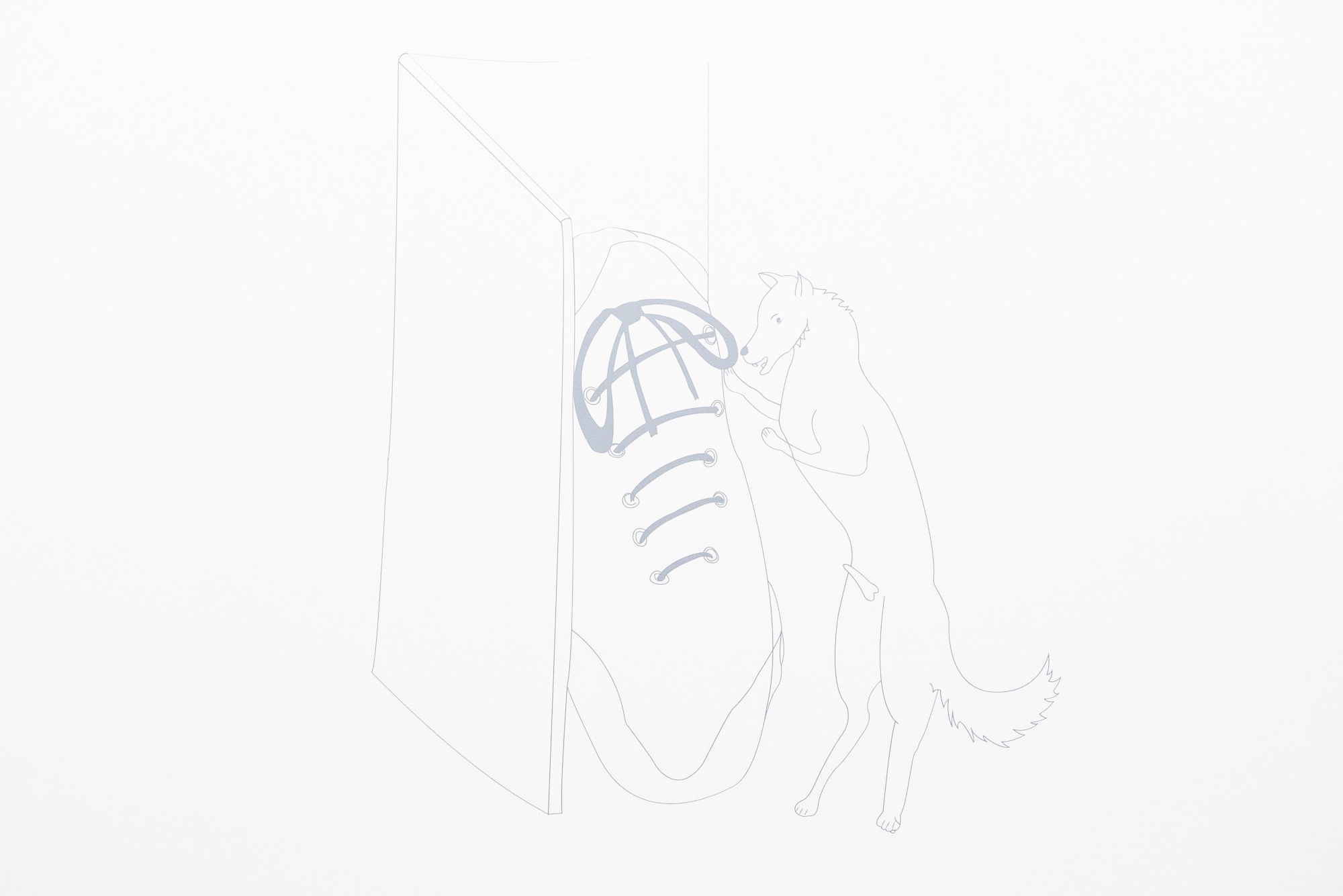

Casual job prospects during Melbourne’s lockdown have been a warped, stilted and disorienting process. Casuals have borne the brunt of job losses arising from the global pandemic. There are harsh realities in abruptly being “laid off”, job hiring freezes by major universities, “voluntary” redundancies, being stood down or having hours reduced. It puts pressure on those forced to undertake the inevitably time-consuming and often punitive tasks of applying for the Australian Government’s JobSeeker or JobKeeper payments. Beyond these recent structural setbacks, there is also a level of absurdity present in the precarious casual job market with respect to the notion of “climbing” the ladder of job opportunity. Reflecting on her previous employment as an usher at a renowned performing arts centre, Hobba plays on this farcical reality in Wolf at the Door Tells Shoe in the Door That the Only Thing to Fear is Fear Itself (2020). The work is a drawing of a comically large foot with long floppy shoelaces sitting in the foot of a door greeted by a depiction of a wolf-like creature standing on its hind legs with a tiny erect penis. Two visual idioms collide: foot in the door, signifying the initial first step to further employment; and wolf at the door, signifying someone or something facing imminent financial ruin or difficulty. To add to the mix, the platitude “the only thing to fear is fear itself” is the advice or response to the giant foot in the door, given by the wolf. The shoe calmly replies, “Oh, okay”.

Once again, an encounter is manifested, dispersed and reimagined into other facets of the exhibition. Plaster casts of the word “OK” are stacked up into piles on the floor, as if the reply has been appropriated, marketed, manufactured and mass produced into its own motivational signs soon to be propped up on the office desks of fellow colleagues. Or consider the precariously balanced iPhone playing Reminiscent OK Screen (2020), a rendered video of the same “OK” logo jumping around a white cube. Like the celebrated bouncing DVD logo failing to ever hit the corner of your TV screen, it is not too far-fetched to imagine this video playing in the hallways outside an office meeting room or turned into default screensavers on work computer monitors.

The final line of this absurd narrative, which seems to have been edited out of the wall text but is included in the exhibition’s catalogue, is not to be left neglected or unexamined. “That was the year (something) happened”. For Hobba, “going postal” or the failure to “go” is the something that happened. But in the wider context of the exhibition, this line speaks volumes. It is both timely and a freaky coincidence that Hobba’s work has been on display in a year we’ve all, in some sense of the phrase, gone postal.

Going postal, of course, is an expression originating from a series of incidents from the 1980s to 1990s, when a number of United States Postal Service (USPS) workers went on murderous rampages shooting and killing their managers, fellow co-workers, police and members of the general public. Since then, the phrase “going postal” has come to refer to a state of extreme and uncontrollable anger, and often violence, usually exercised in a workplace environment. It is a timely reference in the context of last month’s attack on the USPS by the Trump administration in an attempt to intentionally slow down and delay mail-in ballots for the United States presidential election in November 2020. Coronavirus is also putting pressure on Australia Post, which is literally going crazy redirecting Victoria’s mail thousands of kilometres to Sydney processing centres in order to ease pressure on the State’s understaffed parcel delivery systems. Beyond these coincidental circumstances of 2020, the fantasy of going postal that unravels in Hobba’s exhibition (co-conspired by our hero X) speaks to and of a deep unrest within our own collective unconsciousness towards our employment or lack of it.

The second gallery space is slightly smaller and lined with frosted windows tagged with random graffiti. Natural light shines through these windows into Alex Cuffe’s exhibition Love is the Length of Her Hair. It includes a borrowed black steel clothes rack as the support structure holding a row of forty-three white t-shirts on plastic hangers, all ranging in size, each with a digitally printed photo of the artist crying. These crying selfies represent “every time the artist has cried” over the span of five years, a period spanning Cuffe’s gender transition. Although the majority of the selfies are concealed or obscured in the exhibition’s documentation, the exhibition’s promotional image, Uncanny Selfie (2020)—a portrait of Cuffe standing outside on a breezy street in North Fitzroy wearing one of her own crying selfie t-shirts, oversized and comfy-looking—gives us a small glimpse as to what lies ahead in thumbing through the rest of the clothes circulating on the rack.

The act of crying can be easily forgotten or hidden (by those who are doing the crying). When a record is kept, a visual one in the case of Cuffe, it becomes easier to pin-point and recall the time and circumstances of these moments that enabled such a manifestation of unidentifiable emotion—too many to list here. In the late 1990s, poet Mary Ruefle kept a “cryalog” while she was going through the side effects of menopause. Ruefle’s analogue record keeping used shorthand notation: C denoted crying, the number of Cs representing the number of times she cried, and NC indicating that she did not cry on that day. The brevity of these records amplifies these private emotional acts. I wonder what Cuffe looks like on days when she doesn’t cry or if any of her crying selfies were taken on more than one day.

Crying selfies are inherently performative. Tears need to be shed to be documented. The motivations for producing these acts of self-representation are of course, wide-ranging, personal and circumstantial. Often selfies are just taken simply for oneself—there is no rationale needed. But what happens when these private moments, intensely personal ones that carry a certain level of vulnerability (crying), are publicly shared? A couple of precedents to Cuffe’s crying come to mind. In Bas Jan Ader’s I'm Too Sad to Tell You (1970), a photograph of the artist crying, Ader gives no reason for his tears; crying is only performed and recorded. There is a look of sadness, but it is not explicitly shared with us. In Hayley Newman’s Crying Glasses (An Aid to Melancholia) (1995), the artist does not initially reveal to us a motivation for her actions. In both works, manufactured tears are forgotten; the image stands in place for the performance.

What can be sensed in Newman, as it can be in Cuffe’s crying selfies, is the separation between the decisive moment the photograph was taken and the artist’s own recollection of crying in that moment. Shedding tears and shedding selfies go hand-in-hand—both are acts of externalising, documenting and discarding. Like tears, selfies dry up. Both physical and emotional distance from these images allows a space to open up for reflection, including for remembering how one looked when experiencing such internal emotions. As Cuffe aptly tells me over the phone, “To make something vulnerable visible is a way to disarm it but also be with it.” Her crying selfies are meant to be remembered, looked at, literally worn, held up by bodies, breathed into and loved.

The t-shirts were intended to be available to purchase with profits to be donated to Indigenous families affected by deaths in custody. The economy of crying, as a transactional stand-off between viewer/buyer and maker, was frustrated by the COVID lockdown preventing opportunity for the t-shirts to be sold. However, prior to the exhibition Cuffe had gifted misprints of the t-shirts to people she saw. The initial intention—to put identity up for sale—collapsed into the artist’s own kind of care economy that preceded the exhibition; acts of love and kindness survived even when the chance to be confronted with delving into the complexities of a monetary transaction/purchase of the work was voided.

Idly sitting alone on the floor opposite the rack of t-shirts, a white plastic diffuser emits synthetic oxytocin mixed with a saline solution. Oxytocin, the hormone sometimes referred to as the love hormone, is produced naturally by our bodies. Closely related to dopamine and serotonin, oxytocin is also responsible for emotional bonding. But as the diffuser doesn’t produce a scent and its effusion isn’t clearly visible to the naked eye, being physically in the gallery space is the only way to inhale in the work (even if you feel incapable of love). The threshold as to where this work “sits” is decided by Cuffe, as part of the work’s title implies, “… the name of this work is somewhere inside you while you inhale”. As a consequence, oxytocin allows the viewer to give the work its own title. I’m going to call it love.

The exhibition also includes a white washcloth stained with peachy coloured hair dye delicately pinned to the gallery wall. It sits alongside a silver engagement ring held in place by a plaster cast of Cuffe’s own ring finger, protruding out of the opposing gallery wall. Both objects hold great emotional weight for Cuffe, who is unable discard or throw them away. The number of tears cannot be counted on the washcloth, taken from the hospital where Cuffe underwent gender affirming surgery last year. Nor can we see the amount of heartbreak on the wedding ring, which physically had to be cut off Cuffe’s finger before her surgery, which signified a time her wedding was cancelled two days before it was due to occur. Yet each of the titles add to this emotional weight, as they are tenderly written in a loose narrative diaristic form, crucially detailing an account of such life changing moments.

In early September, I managed to watch via Zoom (thanks to the luck of living in the AEST time zone) American poets Henri Cole and Forrest Gander discussing Cole’s new book of collected poems, Blizzard. During question time, Cole was asked what it’s like to promote a book that was conceived in a separate paradigm from the COVID-directed one we exist in today. Cole replied, “We live in this moment in which we feel the voice of the radio, the voice of the TV, the voice of the politicians, the voice of the dictator. All these loud voices. I think confinement has made me feel a desire to hear one voice, a kind of inner voice.” Mid-sentence, he leant over to his windowsill and grabbed a giant shell, propped it up to his ear, and spoke of the yearning in these times of solitude to hear just the one voice of the shell, a kind of inner voice which he described as akin to the voice of poetry, where just one voice speaks to another. Weirdly, the weekend before, I also managed catch the first online launch of Blizzard (also via Zoom) where Cole was asked about loneliness and solitude as a generative or subversive state. Cole again reached for a shell, this time a smaller one, and placed it at his ear, and spoke of poetry being like one “voice speaking and connecting to another voice.” What is it about Cole’s repetition of his performance? Is it that Cole’s solitude becomes authentic only through its performance?

To shake the loneliness, I speak to both Alexes over the phone, much like Cole might talk to his shells in private. During these strange times, what both these exhibitions have become without the intentions of either Cuffe or Hobba (they also both conceived of these shows pre-COVID) is that they are their own versions of themselves, speaking and connecting to me in this moment of confinement. Floating about on the computer screen, instantly accessible with a few clicks, tapping into my own inner voice.

You can view documentation of Alex Hobba’s exhibition here and Alex Cuffe’s exhibition here.

Chelsea Hopper is a writer and curator based in Narrm/Melbourne.