Sweeney Reed and Strines Gallery

⬤ Heide Museum of Modern Art 25 Aug - 24 Feb 2019

Melbourne’s favourite outta-town gallery hits peak-Heide for its summer shows. Heide’s dedicated purpose, a laser-like focus on the circle around patrons John and Sunday Reed, has been disarmingly effective. The propaganda research on the couple is now unparalleled in Australian art history. Controversially, I have no problem with this. I know many do—Sidney Nolan for one would puke in his grave upon learning how he has been absorbed into the institutions’ mythology. Dedicated art museums, in which small institutions are devoted to one artist (or one group) are common outside of Australia. I might be exhausted by those same two-dozen Albert Tucker photographs showing the young Reeds and their kept-artists, but I’m not about to blame Heide for flogging them.

Sweeney Reed and Strines Gallery is devoted to the circle around the Reeds’ son, Sweeney, via the two galleries he directed: Strines (say it in your ocker voice; the 1960s version of ‘Strayans’), on the corner of Faraday and Rathdowne Street, Carlton, run from 1966-70; and the eponymous Sweeney Reed Galleries, on Brunswick Street, Fitzroy from 1972-75. This is not Heide’s first exhibition on Sweeney, his own artwork was shown in a retrospective curated by Max Delany. But that was over twenty years ago, so the present exhibition is more than due.

I say we’re hitting peak-Heide because the several exhibitions on offer beside Strines include: a heartfelt display of drawings and wonderful dolls by the late Mirka Mora (in which the curators’ affection for the artist has allowed the inclusion of a slideshow room exclusively screening images of Mora, inadvertently giving visitors the impression that they ran out of art); a rickety ‘collection highlights’ show (including a mini Danila Vassilieff display in the very room in which Vassilieff died—the Heide I library); a collection hijack by curator/artist Glenn Barkley; a feature on Danica Chappell’s beautiful contemporary camera-less photographic abstracts, and a large display of the Tucker oil-paint portraits, most in his deluded late-style. I came for Strines but, as always, was distracted by everything else.

When you walk into Strines there is an enormously exciting selection leading into the ‘bedroom’ space, beginning with Sandra Leveson massive and angelic screenprint-painting Empryean I (1975), tucked behind the greeter’s desk. Turn around to find a haunting Jean Langley painting of a face stretched within a daisy chain from circa 1960. Enter the ‘bedroom’ and find a crisp square Margaret Worth, a full display case of visual poems by underappreciated concrete poets such as Thalia, Ruth Cowen, A.C.R. and Karen Cherry, and a surprising painting by Leonora Howlett, an artist I did not know but was grateful to meet.

I was thrilled. These are the kind of under-exhibited works you discover when curators go in-depth, specific, specialist, rather than parading the usual over-exposed highlights. Homing in on Sweeney’s galleries uncovered ignored artworks that now look fresh and intriguing. Or so I thought. My enthusiasm was knocked down a peg upon reading the label for Lesley Dumbrell’s Red Shift (1968): “In 1970, Lesley Dumbrell held the only solo exhibition by a female artist at Strines or Sweeney Reed Galleries in almost ten years of operations.” So where, if not Strines, did all these works come from? Another label helpfully explains: “Of the approximately 120 artists Sweeney Reed exhibited, only six women working in a then-contemporary style were included in either space.” It goes on to say that this small ‘bedroom’ display is stretching the exhibition premise, intending to show women who were working at the time alongside the few that did exhibit with Sweeney.

I give credit to curator Brooke Babington for this tactic that highlights, rather than shies away from, the reality of these two galleries. This ‘stretch’ is why the bedroom space also reads quite haphazardly: it mixes Dumbrell’s 1968 work with a 2010 screenprint by Bridget Riley. It’s also the rationale for hanging a local insider figure like Langley opposite Virginia Cuppaidge, who in 1975 (the date of her work) was exhibiting as a lyrical abstract painter in New York (Cuppaidge moved back to Australia only last year).

Moving through the rest of the exhibition, I start to see this delightful beginning as a compromise—but a compromise of what? The remaining work is strictly devoted to artists exhibited in Sweeney’s two galleries, and what this historical purity turns up is unequivocally less interesting. Some artists who are admittedly less saturated, such as Les Kossatz, John Krzywokulski and Ken Reinhard, get a prominent showing that is befitting Sweeney’s ardent support of them. Two Mike Brown pieces show him at his most chaotically fun. These are supported by works that aim to give context to—lord have mercy—The damned Field exhibition. Strines showed a lot of the artists who ended up in John Stringer and Royston Harpur’s 1968 Field show (which is at the blessed end of its golden jubilee year). Yet this achievement is not singular, with Sydney’s Central Street Gallery hosting most of these artists in their stable first. I suppose a handful of the more impressive ‘Field-adjacent’ artworks would have been more striking had they not recent been aired at Charles Nodrum Gallery’s thoughtful show, Abstraction 17: A Field of Interest, c. 1968.

These three themes: tangential women artists, Sweeney’s pet artists, The Field curation, then must contend with a fourth theme—the four publishing presses that Sweeney began, and his own career as a printmaker and concrete poet. Conceivably, I can imagine all this fitting into one exhibition, but here it appears lumpy and bracketed. I was most excited to see these poems and prints, hoping to get a sense of the active visual poetry community in which Sweeney was a huge part. This last section, tucked into the kitchen/laundry space against a large and poorly positioned Allan Mitelman painting, is a letdown. I did not feel I could appreciate this aspect of the show in relation to what proceeds it.

So let’s circle back to my initial thoughts on the Heide spin-machine, and examine the purpose of this exhibition. Clearly, as the title suggests, it is to introduce Sweeney Reed’s professional and artistic achievements to the current generation of Heide visitors. Especially apt, since those achievements were heavily subsidised by his wealthy parents, who also acted as his patrons. Sweeney’s galleries were barely solvent without the Reed’s financial backing.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

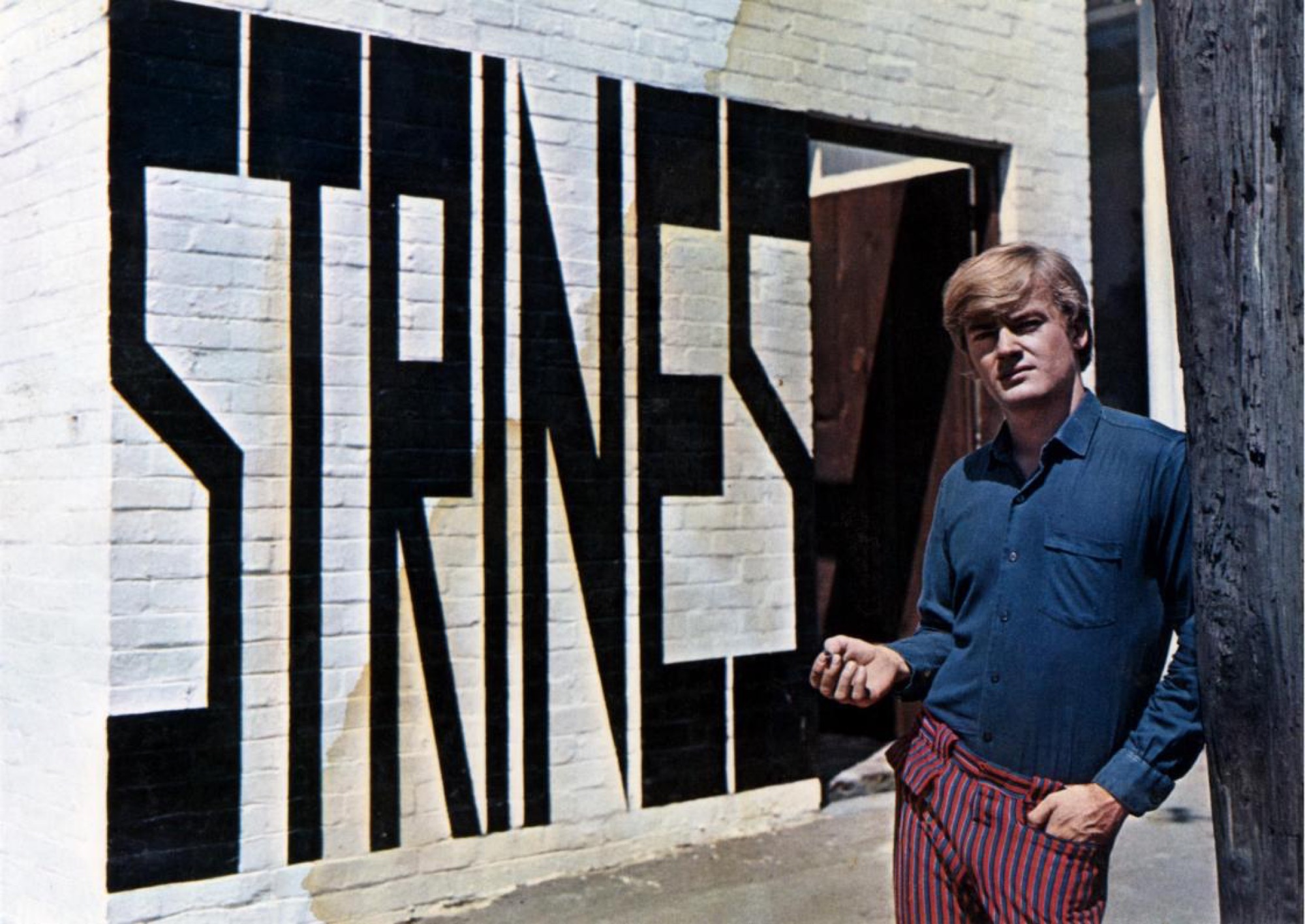

Sweeney (as a baby and toddler) is present in many of those Tucker photographs I decried earlier (Tucker was, of course, understood to be Sweeney’s biological father, although perhaps that was not the case). Heide visitors are used to him as a child, sweetly dressed with a plethora of beautiful parents; but here he is reintroduced as an adult. I do not think it is a coincidence that the exhibition features more than a few publicity images of grownup Sweeney, posing and handsome and blond. Looking at these I hear Janine Burke’s incredible (and devastating) sizing up of the troubled man: “Sweeney was neat, small and blond with a dramatic jaw … and very large, beautiful blue eyes marked by dark lashes and brows … If he had been taller, he would have been dazzlingly handsome. As it was he seemed out of kilter, as if he had stopped growing when he was fourteen or fifteen.” Staged press photography can be deceiving.

In the catalogue—available online here—Babington explicitly expresses the desire to move Sweeney Reed and Strines Gallery away from Sweeney’s tragic biography. This is a request that doesn’t really fly in context. Heide is an institutional success-story built atop a series of sad truths; both Sweeney’s parents killed themselves at Heide (John by self-administered euthanasia, and Sunday, days later, in grief). I too believe that Sweeney’s own suicide should be placed at a distance from an exhibition on his professional career(s). However, I do not believe Heide can both encourage an extensively personal, intimate, all-pervasive mythology of their artists and founders, while at the same time reject the aspects of their biography that they contend “overshadow” their curatorial projects. Here, in his parents’ house, least of all. Biographical discourse is the art-historical strategy that Heide excels in, yet they are quickly shutting the same door that they seductively beckoned from only moments before.

I’ll tell you why this strategy bothered me: I’ve never been able to forget the awful phrasing of the aside in Modern Love (a Heide published biography on John and Sunday), that an unnamed “number of people believe that, tragically, by this time (10 years of age), (Sweeney) had been ‘interfered with’ by (poet and family friend, Barrett (Barrie) Reid), which could explain (Sweeney’s) sexually precocious behaviour.” A rumour powerful enough to (momentarily) breach art history’s notoriously tight-lipped gag on the topic of paedophilia is a powerful rumour indeed. Barrett Reid was one of the Reed’s closest friends and he has a presence in this exhibition. His bequest also made him a fellow of the museum.

In this, a biographically driven institution, to sequester such conversations to asides in large publications (all but absent from the walls) appears cheap. When we pick and choose the biography from which we wish to avert our gaze the result is a lavender-laced history intended to sell magnets and cookbooks.

‘In the father’s house’, there should be a proper place for Sweeney. As Burke also writes of visiting Delaney’s 1996 exhibition: “I’ve been dreading … that the show will look poor, weak and unconvincing. A failure. But Sweeney’s work looks sumptuous. A fully realised vision. Consistent, clear, soft and strong.” I wish I had seen that 1996 Sweeney Reed retrospective. Perhaps then I would understand his contribution and his galleries better. Do I admire Sweeney? Do I think he was a good curator? Artist? Public figure? Walking out of Strines I’m left only with the sense that this wheeling-dealing, free-spending, “art-demon”, blond-Adonis is just another Heide myth, waiting to receive its due complexity and depth.

Victoria Perin is commencing her PhD at the University of Melbourne. Her research concerns printmaking in Melbourne during the 1960s, 70s and 80s. In 2013, she was the Gordon Darling Intern in the Australian Prints and Drawings Department at the National Gallery of Australia.

Title image: Sweeney at Strines, Carlton c.1967, Photographer unknown. Heide Museum of Modern Art Archive. © Lansdowne Press.)