Interview with Catherine de Lorenzo, Alison Inglis, Joanna Mendelssohn and Catherine Speck

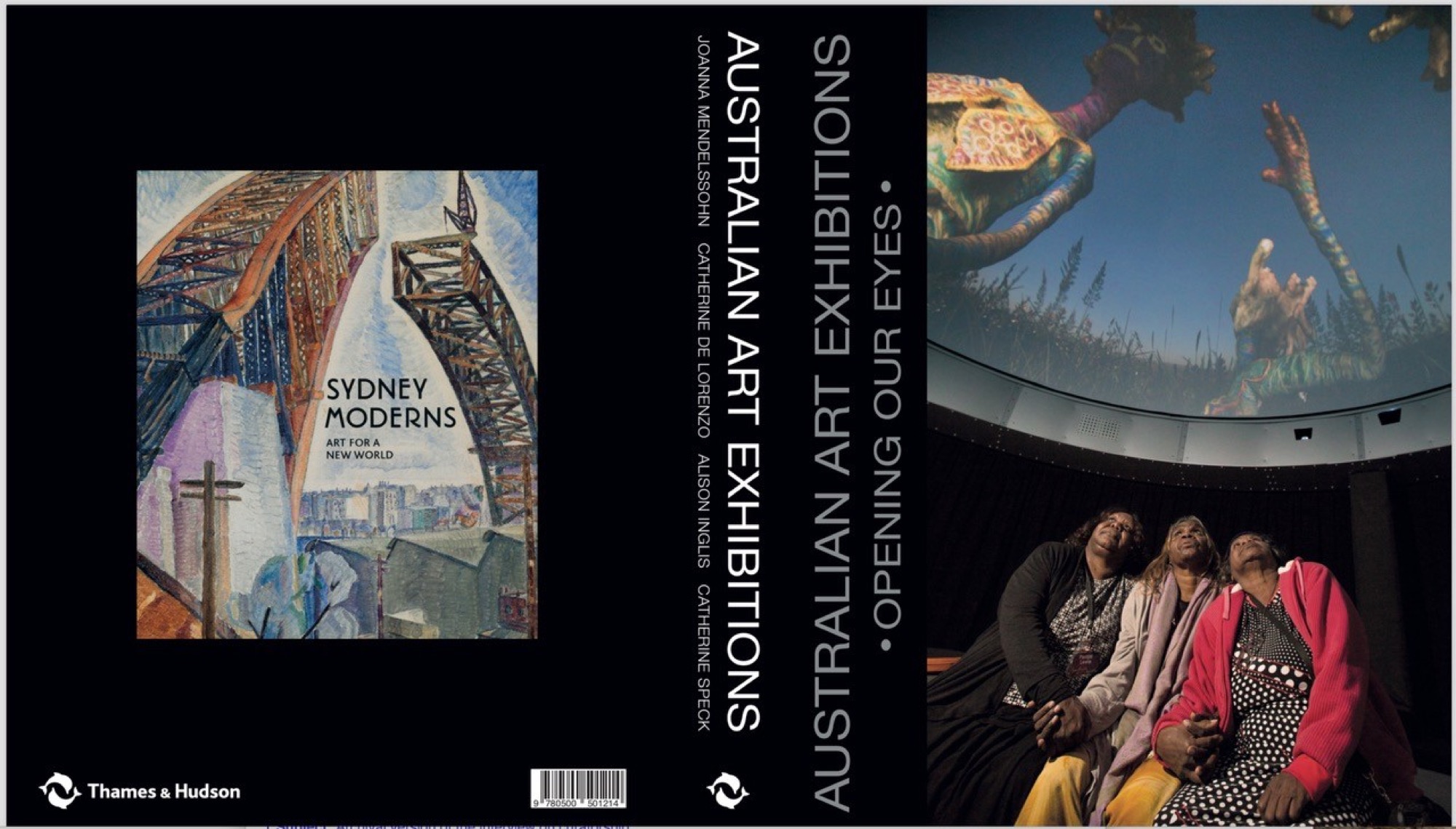

This week the Art Association of Australian and New Zealand held their annual conference at RMIT University in Melbourne. Given that nearly all of the writers for Memo Review are art historians, we thought that this week we would take up the subject of art history itself. But also, given that Memo Review reviews an art exhibition every week, we thought it would be interesting to take up the subject of art history and the art exhibition. Luckily, four Australian art historians—Catherine de Lorenzo, Alison Inglis, Joanna Mendelssohn and Catherine Speck—have recently published a book, Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes (Thames & Hudson, 2018), a history of the art exhibition in Australia since 1960, and Memo Review interviews them here.

Okay, everybody, could you please tell us readers what the book is about?

JM In a way, it's a love letter to the profession of museum curator. Actually, the subject of the book is something we were trying to explain to ourselves while we were writing it.

CS It is a history of Australian art told through its exhibitions. Conventional art history and even the new art histories are so much centred around the figure of the artist. This is a more Bourdieuian history in that it is institutional. It is, of course, still about art and artists. But it is also about institutions (gallery directors, the arts policies of the day). The shift to the Asia Pacific. We try to take account of many of the things that are usually overlooked in writing histories of Australian art.

When does your history start?

AI Well, we say it starts in 1960, but it actually starts in 1957 with a certain shift in attitude towards Aboriginal art.

CdL We try to put the flesh on our institutions. Recover the people who have been lost. We found a photograph of Nicky Draffin, curator of Prints and Drawings at the NGV and AGNSW, looking at a drawing by Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack and we were able to put that in the book. It is not a dry institutional history. Institutional histories can be exciting.

AI When we started this project eight years ago, we looked around at comparable books, both here and overseas. Of course, there are books on famous exhibitions in the 20th century. There is Degenerates and Perverts on the 1939 Herald exhibition at the NGV here. There is today the restaging of historical exhibitions. Curating is an emerging discipline in art history. I think we're trying to complement and expand on these efforts.

What ends up being different about a history told through exhibitions rather than artists?

CdL The relevance of government policies to art. This is not to say that artists don't ever respond to this kind of politics. They do. But it does show how arts institutions respond to opportunities. One of the upshots of our research is to see how arts policies both enable and take things away. For example, during the Whitlam era we had the first small catalogues done for regional galleries with scholarly essays. We find art historians at work there, not just doing things at universities.

AI We have the Australia Council for the Arts determination to fund only contemporary art. It will no longer fund historical exhibitions.

JM Another factor we look at is the credit squeeze of the mid to late '70s and the resulting mega inflation. Also, the deliberate strategy that led to the end of the Australian Gallery Directors' Council. This would resonate in the following decades. For example, we don't see historical exhibitions again until 1988.

CS Yes, we excavate the whole history around the Australian Gallery Directors. They first meet in 1948. By 1958 they wanted the general public to understand Aboriginal art. They commission Tony Tuckson to begin to work on some collaborative exhibitions. This kind of thing is completely absent from most accounts of Australian art.

AI Then we take up the different types of art exhibition. The blockbuster and the survey with their different formats. The travelling exhibition. And we don't just deal with Sydney and Melbourne, but also Adelaide, the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane.

CdL The regional galleries. Campbelltown and Casula.

JM Community arts, where the process is as important as the outcome.

Well you're four women art historians. Was looking at Australian art through exhibitions somehow a way of bringing women artists to attention in a way ordinary art history could not?

AI There is a chapter of our book called 'What about the Women?' And we also look at the women art historians and the women curators. And all of us are writing from our own experiences and memories.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

CdL The book isn't simply revisionist. But it does attempt to expand the usual notions of Australian art, which of course prioritise painting. We speak of photography, community art, printmaking. They are occasionally featured in special issues of journals, but that's about it. Here we try to show the continuities between the different modes of art-making.

The book is on the new topic of curation.

CS It is a recalibration of the history of Australian art. It so often goes directly from Australian Impressionism to Australian Modernism. But this is to elide what we call the centenary years, which feature sculpture, the beaux-arts. The centenary years here are treated fulsomely.

JM We note how ground-breaking Ted Gott's Don't Leave Me this Way: Art in the Age of AIDS at the NGA in 1994. It's still such an important exhibition. As we writes, the Brooklyn Museum made a fuss about putting on the first big American AIDS show. That was only a couple of years ago.

AI For the general public, we are expanding the idea of what art could be. There was a shift in the exhibition of Aboriginal art from ethnology to art and from colonial art from Australiana to art.

Yours is a historical study. But what do you think of art exhibitions in the age of the internet? And of the blockbuster as the dominant mode of exhibiting art? Are art exhibitions coming to an end or still going?

JM Art catalogues are definitely moving more online. No more heavy publications. The National Gallery is putting everything online. As for the blockbuster, the first was Golden Summers: Heidelberg and Beyond, NGV, 1985. When that happened, Patrick McCaughey wanted to borrow some works for the NGV. But the only way he could do that was to use the government art indemnity of Art Exhibitions Australia (formerly ICCA). It was the most profitable art exhibition ever in Australia. The catalogue sold 100,000 copies. It was done on shoestring.

CdL The huge problem is that tourist organisations will only fund overseas exhibitions.

JM That's why the APT is so important. That's why the early period of the 1970s when the money was available was so important. New galleries and universities got a new lease on life by bringing people in. But not a lot of catalogues from the time have people's names in them. They were slim modest things. There is just an emphasis on the work. But I think the model of the scholarly catalogue has a lot of merit. Major exhibitions do not have to a doorstopper of a catalogue. Creative and innovative things do not require money, but they do need support.

Is the future of exhibitions online?

CS I disagree with that. I don't think the future of the exhibition is in danger. The art exhibition's future is alive and strong because of the current drive by successful directors to bring the public through the door. But altogether we have been slow to grasp the importance of exhibitions because of the emphasis on the artworks and collections.

AI The flipside of the digital is an enhanced interest on the object. Read a lot online, then they want to go to the exhibition to see real objects in space. We fetishise the real in a way. At the moment, in art history publishing what is the most obvious way to get out to the public? It is the exhibition catalogue, which has produced exiting revisions of art history. Australian Impressionists in France; Hilda Rix Nicholas; Bauhaus on the Swan. There is a lot of great work in catalogues that we celebrate.

What have been your favourite exhibitions since writing the book?

AI Colony. There was Indigenous curatorial agency. There was the idea that Australian colonial art couldn't be discussed without the question of white settlement.

CS William Kentridge: that which we do not remember at the AGNSW. It featured multiple artforms. It was tremendously exciting.

AI We focussed in the book on Australian art exhibitions. But there are also fascinating exhibitions overseas. The next task is to look at them together.Title image: Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening Our Eyes (Thames and Hudson), Joanna Mendelssohn, Catherine De Lorenzo, Alison Inglis, and Catherine Speck.)