In Kieren Seymour’s previous shows the focus was primarily on human and human-like figures—sometimes friendly and cartoonish, sometimes reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s violently fragmented dolls. In Blue Blindness these figures re-appear, but Seymour turns away from their personalities to explore questions about the nature of perception and the relationship between a brain and a world.

The phrase “blue blindness” comes from a fact told to Seymour by a friend: when you are depressed or “blue,” you actually have less capability of seeing blue. Depressed people see less blue in two ways: clinical depression hampers one’s abilities to see bright colours—including blue—and contrast so that everything appears greyish; and, a lack of exposure to blue light, not the white light of the sun as one might think, is the cause of seasonal depression. While we may think that the source of happiness in summer is simply the sun, it is actually the rays of the sun as they scatter hitting the Earth’s atmosphere, turning blue in the process. Blue Blindness has lots of blue, bright colours, and contrast, which even through a grey haze of depression might be legible.

If the answer to the naïve question “why is the sky blue?” is “to make us happy,” what about its grown-up version: “what is the relationship between self and world?” and the subsequent Marxist and Freudian inflections, respectively, “how much is the broken self a result of the broken world?” and “how much is the broken world a result of the broken self?” In Blue Blindness I find all three registers.

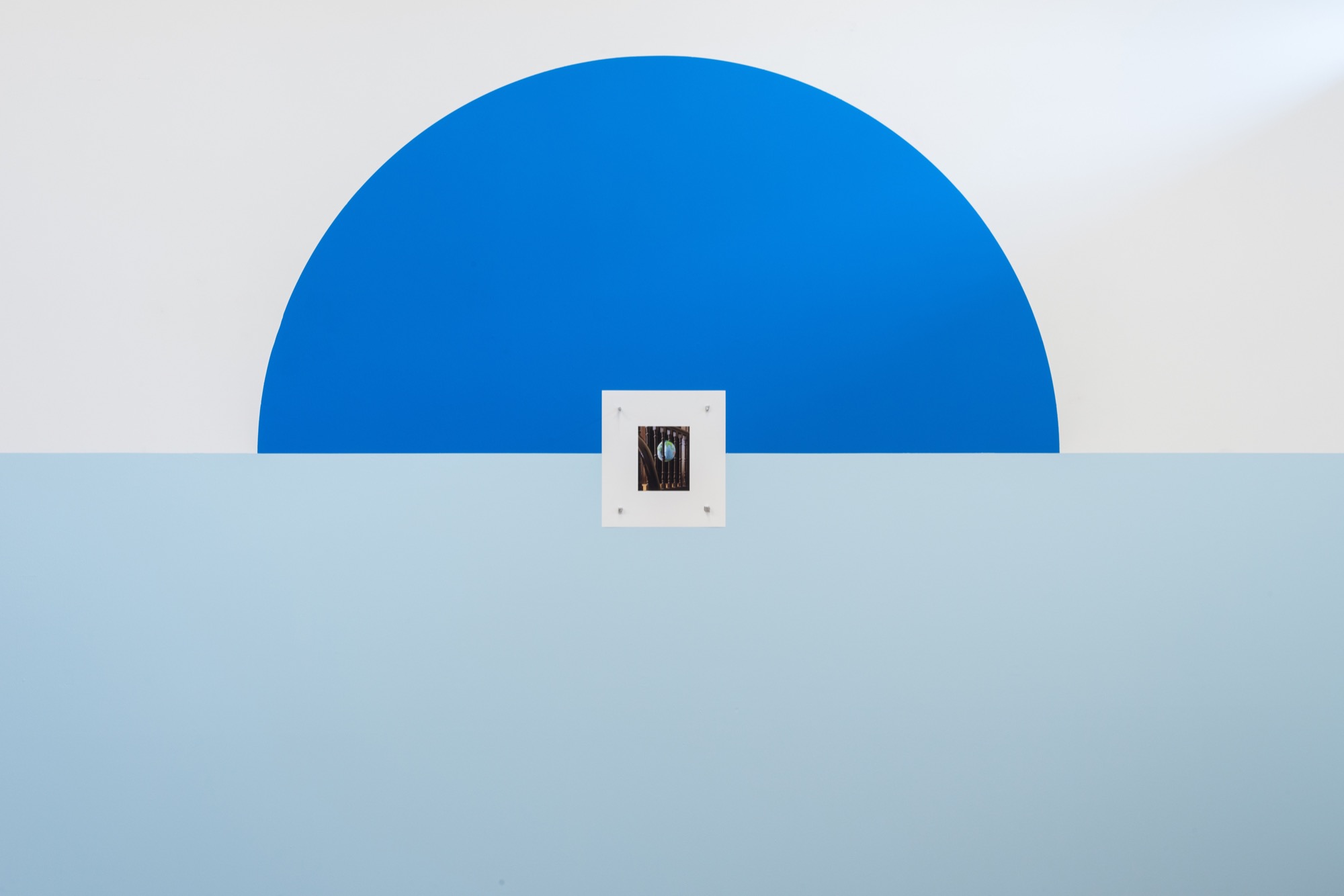

The works in Blue Blindness are mounted on blue walls with cast aluminium shards attached to nails. One wall features a pale blue horizon and a cobalt blue rising sun. At the centre of the horizon and the sun is a photograph of an inflatable globe squashed between glossy brown bannisters. This globe appears again in another work draped on top of a pole, taped to the point of a knife, standing in a foam mattress.

Maps are often inaccurate, and strange failures at representation. The standard world map, for example, is the Mercator projection map, which distorts the sizes and shapes of each continent for the purpose of nautical navigation. A spherical, blow-up map is at least accurate in terms of the sizes and shapes of land and water on planet Earth, yet… it is still full of hot air. Who’s to say a squashed world or a deflated world—especially a deflated world re-purposed to shade you from the happy refracted rays of the sun—is not a more accurate depiction of “the world,” than a blow-up world blown up?

In three works translucent maps are curled into cone shapes and lit up in red, blue and green, respectively. These works reference the cones at the back of the retina that allow us to see colours. The coloured cones are like night lights, dimly lighting interiors that are otherwise pitch black. Many of the works in Blue Blindness feature colourful plastic backlit or illuminated: a green bucket is lit from inside with a skeleton draped over it as a man on a truck looks on; a green man pulling open his head reveals a pink light coming from inside; and subtly illuminated yellow and pinkie-red plastic bottles form the shape of a double helix.

A double helix is referenced again in “Meat in Plant DNA,” featuring a red spiral with toy animals affixed to it, and “Looking Inside,’’ where a polystyrene figure looks down at a phallic green DNA spiral as he cuts a large vagina-shaped hole in his stomach. The double helix is one among many references in Blue Blindness to the current paradigm of scientific knowledge. “New Rind,” the title of the photograph of the world squashed between the bannisters, references the half-peeled mandarin of another work in the show, and is the literal translation of the Latin word “neocortex.” Seymour created the works in Blue Blindness after experiencing the effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), which is administered globally to the brain for the treatment of major depressive disorders. In this context, the green man pulling apart his head in “Inside a Head” seems to be revealing a change within his brain, which allows him to perceive the world differently. The pink light emanating from within also mirrors similar palettes within the show: the backlit plastic I mention above, but also the leaves of a tree in “King Parrot” and the almost florescent greenery emerging from a mound of volcanic grey rock in “Pile.”

Seymour’s work is interesting in that it captures sculpture and installation via photography. In contrast to the illumination and backlighting I have described, which brings dimension to the photographs, the standard lighting on the studio assemblages flattens the images, creating interplay between stasis and movement within each image and across the show. A king parrot takes flight through the branches above the small man side-eyeing a skeleton. A sun, but blue? A stagnant brain, stimulated? This dynamic at times recalls an advertising aesthetic. In one image an excavator shovels dirt amongst the debris of a partly demolished house, but it is “Case,” the lettering on the excavator that Seymour focuses the lens on, capturing it in bright daytime light, similar in effect to flat studio lighting. In another work, the brand of a nail gun, “Paslode Impulse,” is similarly rendered. These images, which depict the building and demolishing of houses, provide contrast and movement to the interior scenes.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

The clean suburban interiors that house Seymour’s messy-but-not-dirty assemblages act as a framing device in a similar way to the scientific references throughout “Blue Blindness.” They work to create a solipsistic, uncontestable place from which to explore the violent and sad dimensions of the human psyche. From here, however, new colours in the brain begin to match up with new colours in the world.

Eva Birch is a writer, PhD student at The University of Melbourne, and Editorial Assistant for Parrhesia: A Journal of Critical Philosophy.

Title image: Kieren Seymour, Blue Blindness, 2018. Image courtesy the artist and Block Projects.)