All reviewers seem to begin by telling us the circumstances in which they came to watch it: when they first came into the screening room, how long they stayed, what they were doing before they came in and what they did afterwards.

The novelist Zadie Smith—when she went to see it at the Hayward Gallery in 2011, in an essay originally published in The New York Review of Books and later used as the catalogue essay when it was shown at the MCA in Sydney in 2012—says she saw the work the first time around 2 in the afternoon, stayed 45 minutes (she wished she had stayed longer), was looking after her kids before and got back to work afterwards.

The author of a long profile for The New Yorker, Daniel Zalewski, came in around 4.30 in the afternoon during its screening for the Yokohama Triennale in 2012, stayed around three hours and left only reluctantly because the artist was with him and tapped him on the shoulder and said he wanted to go to dinner.

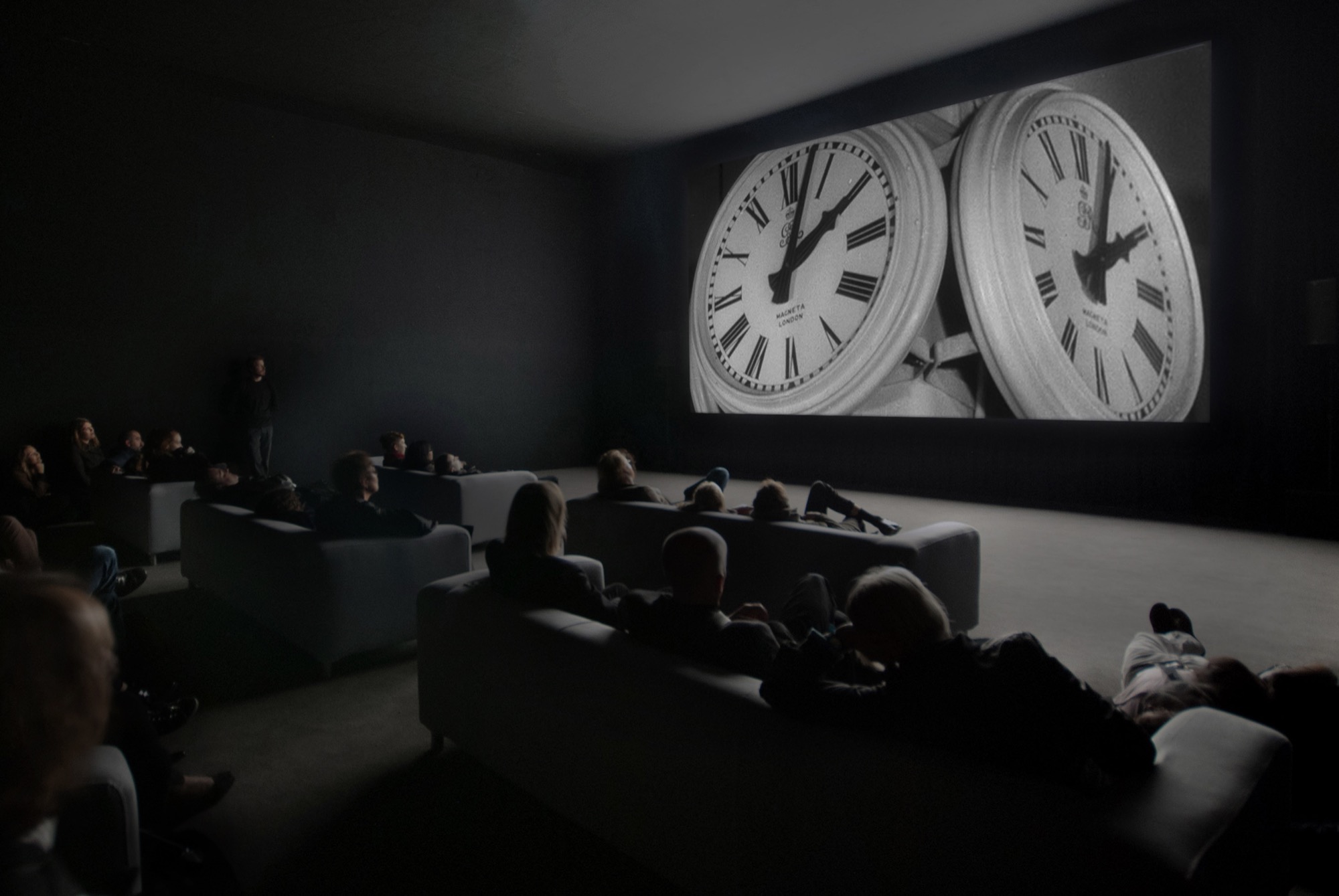

The piece they are talking about is Swiss-American artist Christian Marclay's The Clock (2010), a 24-hour long video installation that is undoubtedly one of the signature works of the early 21st century.

The brilliant conceit of the piece is that Marclay has assembled some 12,000 pieces of footage from the history of cinema that feature clocks, watches and people saying what time it is and edited them together so that the time depicted on the screen is the same as the time in which we are actually watching it. So that, for example, when Ray Milland despairingly looks at his watch as he stumbles out of a bar into the bright sunshine in The Lost Weekend (1945) and it says 12.30 pm, it's exactly 12.30 pm in the screening room. Or if you're still up at 3 am, you're going to see an excerpt from George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968) where the zombies walk past a clock in the deserted town square with that time on it.

12,000 pieces of film, with a few occasions where Marclay cuts back to the same sequence at short intervals to build up suspense or at longer intervals because widely spaced and signposted times feature throughout the plot—by my calculation, that's about one piece of film every seven and a half seconds throughout the 24-hour cycle.

Of course, the thing that leaves audiences and commentators flabbergasted is that Marclay has been able to find a clip (actually, about eight of them) for every single minute of the day. Who knew that in the history of cinema there'd be eight films that feature the same 3.41 in the morning (actually at that time the pace is a little more languorous, so somewhere around 4)? Who knew that 1.43 in the afternoon would be so worthy of note (characters checking their watches, looking up at clocks, speaking the time to themselves or listening to others)?

Marclay, after trying a single hour and deciding it could work, hired a team of some six assistants who took three years scavenging the world's audio-visual archive searching for the missing pieces. Then, having found all of the footage, he was even in the position of rejecting some to allow minor continuities between segments (the firing of guns; couples kissing; eating, sleeping and screwing at their appropriate times), and then hired a sound engineer to lay down a soundtrack that again subtly emphasised short-lived continuities between otherwise unrelated pieces of footage. (Marclay was, in fact, a scratch music DJ before he became an artist and had previously made a whole series of sound works.)

Fear not, all the big hours get their due. The Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly Western High Noon (1952) features at midday. At midnight, we get to hear the orotund voice of Orson Welles declaring the time in Chimes at Midnight (1965). That classic image of silent film comedian Harold Lloyd hanging onto the arms of a clock high up in the air features at 2.45 in the afternoon. We even get Christopher Walken talking about the watch up his arse in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994).

And of course the uncanny thing—it happens only on Thursdays at ACMI when the screening goes all night—is that at midnight the next day ticks over and the whole thing starts again. But perhaps the truly uncanny thing, if we think about it, is that every moment of The Clock is like this: at once an end and a new beginning. Like those lizards eating their own tails at the M.C. Escher show currently on at the NGV, if The Clock is about the relentless passing of time, it is also about its repetition, its recurrence, even its circularity.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

Needless to say, critics and commentators have found all kinds of precedents for Marclay's enterprise, which strikes us at once as immortal (it's from the Ancient Greeks that we get our words for hours, the passing of time and old people) and absolutely of our moment (the work now appears as much as anything like a Google search putting in the words “film” and “clock”). We could start with Marclay's own 1995 short Telephones, which is made up out of clips featuring one-sided telephone conversations in films, or Anne McGuire's The Strain Andromeda (1992), in which she re-edits the 1970s sci-fi classic The Andromeda Strain so that it now runs back to front. We could go further back to Bruce Connor's 1960's found footage assemblages or Andy Warhol's Empire (1964), an eight-hour uninterrupted take of the sun going down behind the Empire State Building. In the realm of great literature, we have James Joyce's Ulysses (1922), which seeks to capture a complete day in Dublin in 1904, or Virginia Woolf's Mrs Dalloway (1925), which similarly attempts to record a day in the life of an upper-class woman in pre-War England.

Tracey Moffatt has been making similar mashups for years—the nearby Screen Worlds space at ACMI is showing, for example, her 2007 Doomed, featuring images of global catastrophe in films from all around the world. Some might even remember the Kiefer Sutherland TV series from a few years ago, 24, in which counter-terrorism agent Jack Bauer fought the bad guys in real time with each season lasting a single day.

I personally would like to put in a plug for Soviet film-maker Dziga Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera (1929), which seeks to show a single day in a big city, with the film slowly waking up with long cuts, speeding up in the middle with shorter cuts and then slowing down again at night with longer cuts.

But I suppose the obvious contemporary comparison—the most revealing and important—is with Douglas Gordon's 24 Hour Psycho (1993), the almost equally celebrated conceit in which by a simple turn of a video screw he managed to slow down Alfred Hitchcock's horror classic so that it gradually unwound over a full 24-hour day.

The effect is a kind of curious suspension of time. Not only can you wander into this much-viewed film and not know exactly where you are, or at least are not immediately able to recognise a scene or sequence you have watched many times before, but as you watch it unspool in ultra-slow motion you seem held in a perpetual present. It is like the slow diminuendo of strings in a classical orchestra, and the film suddenly seems almost improvisational with no clear sense of what will happen next. (Gordon later made a video piece featuring two soloists and an orchestra playing Mozart's sublime Sinfonia Concertante that has something of this effect.)

By contrast, there is a kind of literalness to The Clock with its constant references to the march of time or at least, as soon as you become engrossed in some micro-segment that brings back memories—I was reminded watching Sean Connery handing a bikinied Ursula Andress a watch in Dr No (1962) how I had been inexplicably stirred by this sequence the last time I had watched it as a young teenage boy some 40 years ago—you are jolted back into reality.

Everything passes; art cannot slow anything down and mostly just exists in the same time and space as everything else. Sitting in the dark watching the endless unravelling of Marclay's film made me think of what it will be like going through the pictures of your life in an aged care facility when everyone who has known you has gone, or lying on your side in a hospital bed with your life flashing before you in your last moments. It all came down to this, the simple passing of time on planet Earth. The Clock is terrifyingly stupid, like life itself, most of the time.