Zac Segbedzi and Friends (enemies) Early Career Group Show

Giles Fielke

A black and white image of the contemporary pianist Javier Perianes, a photograph of a cute miniature donkey on Instagram, and a punctuation mark are the promotional material given for a retrospective hybrid solo/group show of work by Zac Segbedzi, titled Early Career Group Show. This is all that appeared before the exhibition opened at West Space, at which time a real miniature pony (apparently toy donkeys don't live around here) arrived with the artist in the gallery, accompanied by hired piano muzak. A digital flyer for the show was also circulated online, made up of parodies of conversations adapted from local commentary on the contemporary art scene in Melbourne: the police, arts administration, theory of exhausted narratives, etc. This is Segbedzi's artistic gambit, one could call it a self-conscious performance of the online troll—usually encountered as a 4chan Incel/Cuck, a confused and/or sick teenaged boy—assimilated to a particular subjectivity as the model of the contemporary artist. The works by Segbedzi, and his friends (enemies), conspicuously installed and mostly wall-mounted paintings, are not uninteresting to encounter in this space, however. Seeing past the defensively “Punk” façade, they become the grotesque results of modernism's forcible mashing together of art and life, a negative Frankenstein. Alt-art that feels very 2018—not just painting and installation, a performance.

The idea of a systematic program for the atrophied breeding of an animal-slave, to the status of lap-dog pet (the small donkey/pony) actualises the sentiment that Segbedzi seems to hold towards the contemporary arts in Australia and in particular Melbourne's inner-west. Stranded on islands in the Mediterranean basin, the animals became tiny. This gesture towards isolated purity is mirrored, perhaps, by the gridded paintings he made and first showed in series at Monash University's MADA studios last year. The (literally) hidden centre of the show, large and calmly offensive swastikas painted on cotton duck within the grid format are included in the retrospective under paper wrapping (censored by the gallery, not the artist; the text makes sure to make the point), suggest a niche scene that takes its references from the bad boys of contemporary painting: some older—Michael Krebber or Merlin Carpenter—or current “stars” like Mathieu Malouf and Jordan Wolfson, or even Chief Keef's Glo Gang enterprising from Chicago drill music to the LA gallery scene. (I also think of Dean Blunt's contemporary art debut, featuring only freshly delivered McDonalds while a siren played on loop in the downtown LA art space.)

Other than the glut of large and cumbersome works by Segbedzi in the show, works by artists (in no particular order) Katherine Botton, Liam Osborne, Grace Anderson, Natasha Havir Smith, Calum Lockey, Hana Earles, as well as a wall-text biography of far-right German AfD politician Alice Weidel, which seems to credit her as an artist in the show, serve to create a sense of coherence and aesthetic style identifiable as specific to a select community of artists working in dialogue as contemporaries.

In Chris Kraus' description of the figurative painter R.B. Kitaj, she seeks to plot out an alternative reality where his work is key to the arts discourse of the 20th century, rather than peripheral to its central, modernist narrative—an interesting idea occurs that seems both to negate the canon as well as attempt to lionise Kitaj's brilliance: 'Curatorial excitement mixed with apprehension: how to make this “difficult” work accessible? By introducing us to the artist as an admirable freak.' Segbedzi and co.'s works are so deliberately freakish in that they all require their own 'spray-painted' didactics—engineered as an exercise in art-jargon by the artist and written by students. Often entire canvasses of painted text are stapled to, or feature alongside, the variously painted works to further 'explain' them to a presumably perplexed public.

West Space director Patrice Sharkey has been bold in offering Segbedzi the show given the current climate of misogyny in Melbourne and the #MeToo moment more generally. Segbedzi's attempt to cut the success of artist Minna Gilligan down to size through the unauthorized exhibition of some of her student drawings, which he showed at White Cuberd, a portable gallery he ran through 2017, was mostly met with consternation. In all, the show seemed designed purely to injure the artist emotionally, but was masked as a critique of the commercial art world and in particular Gilligan's gallerist Daine Singer. At West Space the results of six years of post art-school work still teeters on appearing only as a massive “art-world” in-joke, albeit in miniature. A storm in a teacup. West Space's public galleries allow us to glimpse the private lives of a tiny scene of art-school graduates, as competitive and brutish as they come. The work, therefore, falls by the wayside: this is about the lives of the artists.

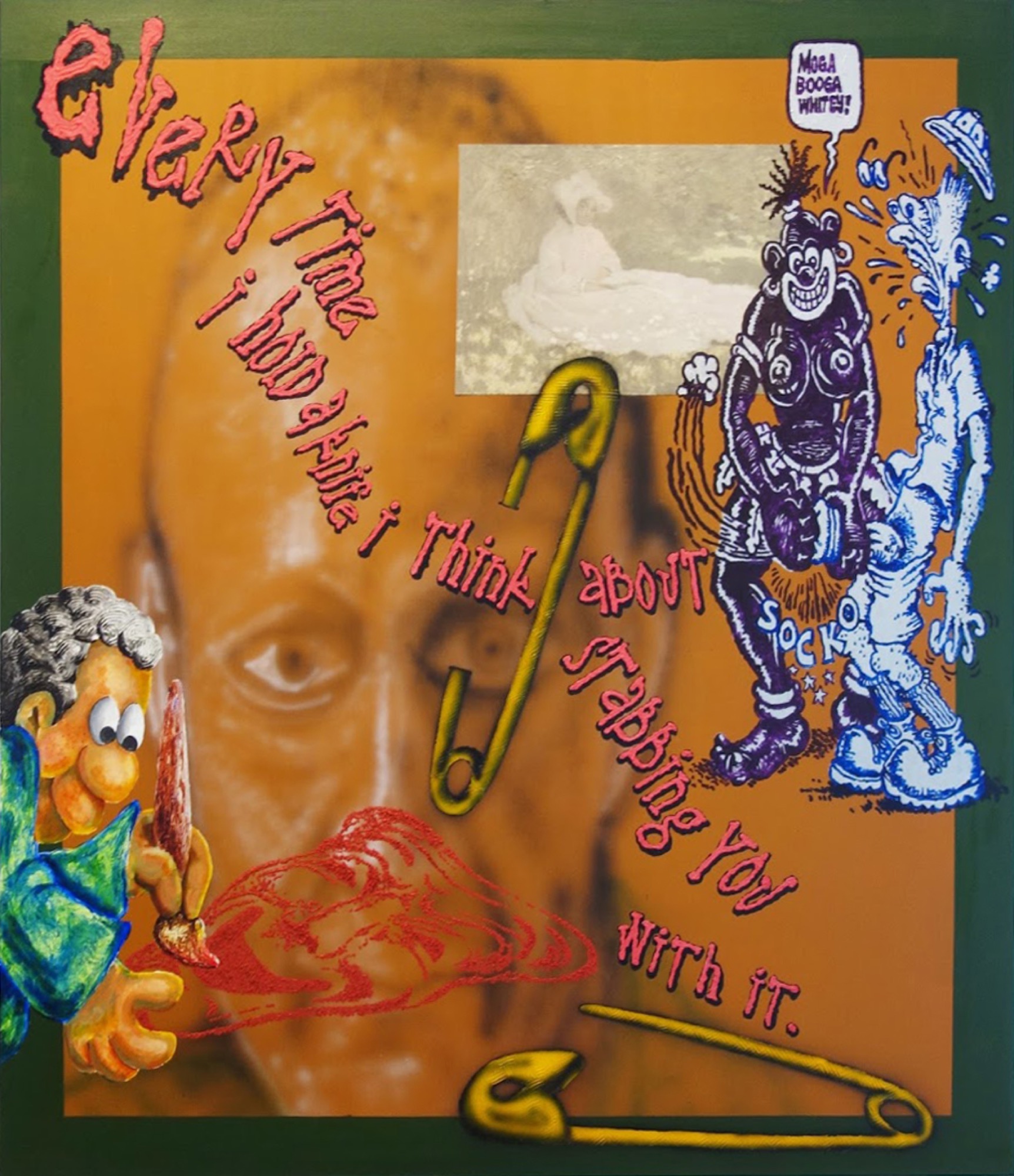

There is no doubt that there is something compelling about a painter whose work could convince Scarlett Johansson's boyfriend to fly in to Melbourne for an afternoon while hanging out on set in New Zealand, just to buy a Segbedzi painting spotted on Instagram to take back home to LA. Is it this fetishisation of the bad boy lifestyle's seemingly limitless resilience that makes Segbedzi an interesting artist, however? Or is it his personal demons, incessantly mined for public content, or is it simply his unmistakable skill as a painter and conceptualist? “Grandpa died in the Holocaust and Daddy abandoned me at birth” is one phrase in the text-heavy show, painted and just visible over a monotone representation of Adolf Hitler. It turns out his father is a billionaire property developer. In another painting his father's portrait appears menacingly, juxtaposed behind a melange of violent yet comical imagery.

Segbedzi is leaving Australia to study in the US. Instead of seeking infamy, it appears he’d rather just be an artist. The artist as a troll (is Shrek the reference here?) is a position that Segbedzi occupies all too easily, but not without the difficulty of knowing that self-deprecation is ultimately limiting. Aim small, miss small. “The failure to prize the chance to spend time in a cosmopolitan city highly enough to refrain from giving it up in favour of an upstart one-horse town,” wrote Robert Walser, before his face-down collapse in the snow, into obscurity, belies the fact that in the provinces the one-trick pony evolves over time, becoming something altogether different from what it once was in the big-smoke of history. The toy “donkey” (i.e., the Shetland pony) may be a freak of biological determinism, but it is a beautiful one.

Giles is a writer and musician working at Monash University and the University of Melbourne. He is the Business Manager of the AAANZ.