Both times I visited Yhonnie Scarce’s survey exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), I entered the wrong way. I couldn’t make it past gallery one, that “massive hangar”, as the artist describes it, into which she has placed three ominous but insistently beckoning sheds, receding in a row into the vast space.

The zinc sheds are found objects—fossicked from a scrap yard—that have been painted with bitumen, lending their black and gold exteriors an oily stickiness. Slightly tacky, slightly oozing, they may well be diseased. And yet the compulsion to open the first shed’s door and go inside persists. That experience—of standing inside that small, dark, grievous, luminous space—powerfully resists language. It is so expressive, so affective as a sculptural statement, that attempting to put it into words for a review like this feels like a fool’s errand. But maybe that’s the point. That resistance to language matters and may be an ethical and political position, as well as an artistic one.

Missile Park, the title of both the exhibition and Scarce’s new commission for ACCA—those three sheds, as a collective installation—is also the name of the public plaza at the entrance to the now shuttered Woomera History Museum in South Australia, curator Lisa Waup notes in the exhibition catalogue. Woomera was an artificial town built after World War II for the British to test long-range missiles, including nuclear weapons. The result is a radioactive desert site the size of England.

The Woomera Prohibited Area (WPA) is riddled with Tarkovskian details, like trees that can only grow to a certain height. Before nuclear testing (which was really nuclear war), the WPA was the home of six Aboriginal groups displaced because of the tests. One of these groups is the Kokatha peoples, to which Scarce belongs (she is a descendant of the Kokatha and Nukunu peoples). She was born in the exclusion zone and “that simple fact”, Daniel Browning notes in his incisive catalogue essay, “still reverberates, casting a long shadow over her research-driven practice”. In two bracing, generous podcasts derived from public programs held in conjunction with the show, Scarce reflects on her home and country, the many depredations inflicted there by the British and Australian governments and the wilful amnesia that still surrounds these events and their aftermath.

The threat of nuclear catastrophe in the postwar era—that odd dual sense of being both after world catastrophe (post-atomic bomb) and before it, in the sense of the ever-present, ever-menacing possibility of nuclear annihilation—was hardly a mere threat for the world’s Indigenous peoples. During the so-called “Cold War” two thousand nuclear bombs were detonated on Indigenous lands and waters, nine in Aboriginal Australia, 814 in the Shoshone Nation in Western United States, to give just two examples. Exploding nuclear weapons on Aboriginal lands proved the tenacity of the logic of terra nullius extended well into the twentieth century. But the reality was far different: death, displacement, radiation sickness, miscarriage and intergenerational trauma.

Stepping inside the first shed (the only one of the three visitors are allowed to enter) and pulling the door closed, I found myself in a dark space, in stark contrast to the brightly lit gallery I had just left. As my eyes adjusted, the space changed drastically, revealing a grid of carefully placed black glass spheres on a table, hip-height, set at the back of the shed.

Light seeped in everywhere—the sheds were pockmarked with holes (pre-formed, surprisingly, not made) and, because of their provisional construction, empty spaces along all joints, through which streamed that bright gallery light. The effect was luminous and dynamic, as if I had entered a dark, sickly shed improbably containing the night sky. The glass spheres faced me, patient and mute, but always reflective of this prismatic play of light, especially a distorted, funhouse mirroring of the door behind me. Spherical, the size of a large melon, and each with a differently shaped wick or stem generated by the glass-blowing process, I first read them as bombs. Then as entities, though not quite bodies. “The truth is in those sheds”, Scarce explained to Browning, “and they’re waiting to be unearthed, to go off really”. The artist names these forms as several things in the ACCA podcasts: bush plums, bombs, the truth and the dead. Writing about her 1966 exhibition Eccentric Abstraction, the American critic Lucy R. Lippard suggested that, “In eccentric abstraction, evocative qualities or specific organic associations are kept at a subliminal level … Ideally a bag remains a bag and does not become a uterus, a tube is a tube and not a phallic symbol”. Scarce does something different: she offers a range of associations, often contradictory, in order to keep the meaning of these glass forms in flux. That flux, or multivalence, or indeterminacy, is crucial, I think, in providing this work with its power. Because the forms never settle into one meaning, a work like Missile Park resists becoming a memorial. Or only a memorial. An overabundance of naming (plum and bomb, military shed and reliquary) is not unlike that resistance to language I mentioned above.

Scarce’s work is now iconic. As the ACCA show demonstrates, though her sculptural work may differ in terms of scale, configuration, shape and connotation, she returns to the same forms again and again: bushfoods, such as yams or plums or bush bananas, hand-blown in glass. And usually a lot of them, such that they become a multitude, despite their fragility.

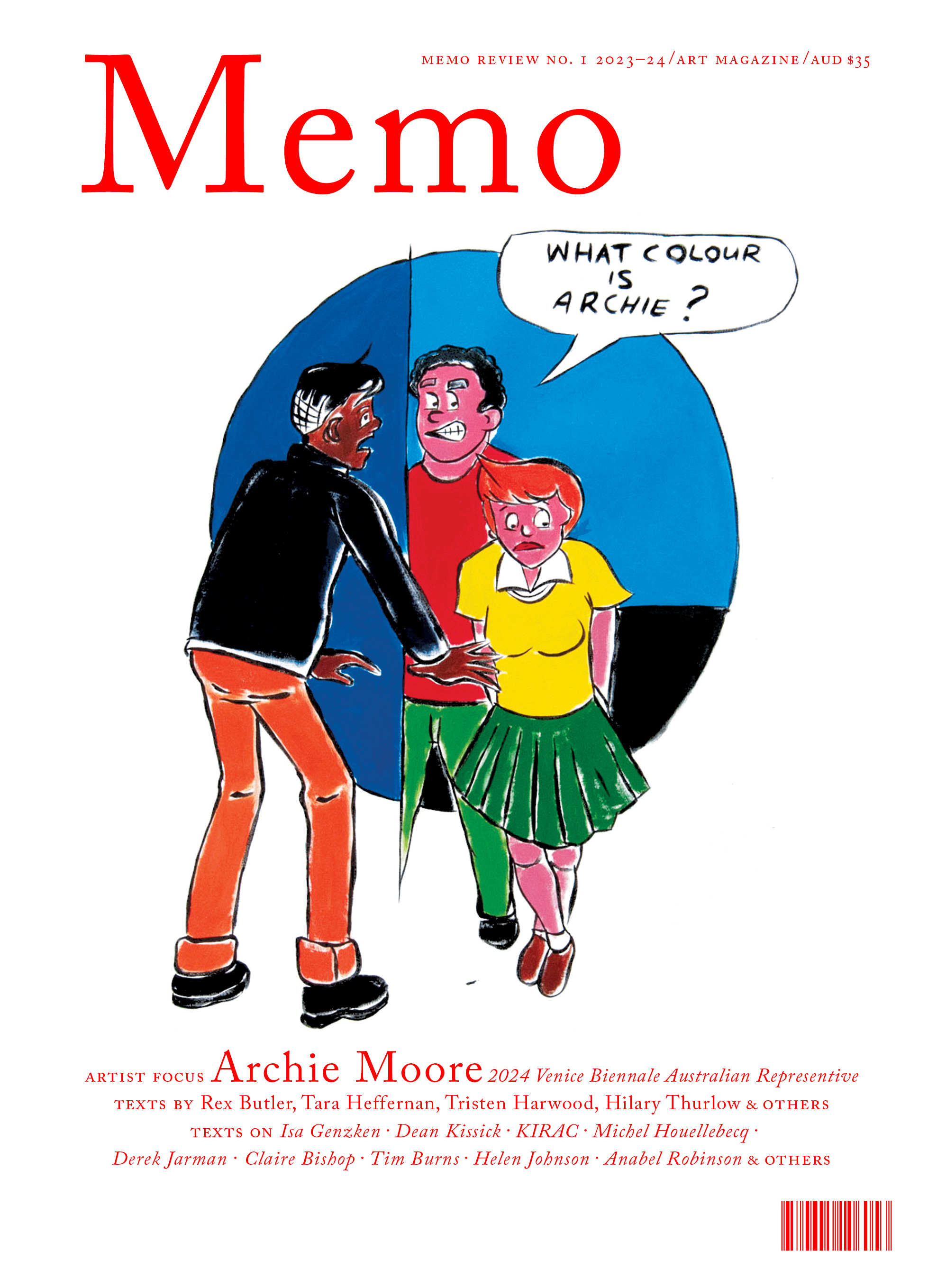

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

In the back gallery adjacent to Missile Park they are laid out in a grid on a low white plinth, almost forensically, in Burial Ground (2009). They appear, one by one, in a precise row along a long white shelf, each incised with a diamond saw and placed inside a laboratory beaker, in The cultivation of whiteness (2013).

They’re piled up into a larger mass and placed inside a Perspex coffin, in Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia, 1849) (2013). Like Missile Park, these last two works carry a specific referent, to books of the same name, further evidence that we are firmly on the terrain of allegory here.

The room-sized installation Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014) was almost unbearable, even though I had experienced the work before at its debut in the 2014 Biennale of Sydney. Three evenly spaced steel trolleys (an echo of Missile Park’s configuration) salvaged from the Ballarat hospital hold three different piles of blown glass sculptures. The trio are enclosed by a clear plastic medical curtain.

Along the two facing walls run white shelves onto which Scarce has placed more glass pieces, most sliced or pinched in the blowing process, the top row with scissors still attached. Standing in that gallery, ACCA’s even, cool, white gallery lighting seemed even brighter than usual. When I asked the invigilator if the lighting had been punched up for the exhibition, I was told that ACCA had upgraded to LED lighting not long ago. It was, indeed, brighter. Though accidental, it made Scarce’s installation appear even more clinical, even more exposed under those unyielding white lights. The relationship was symbiotic, of course: the clean, artificial space of the white cube intensified the environmental and sensorial conditions of this work just as ACCA’s rust-red steel bunker in the urban desert resonated with the sheds placed inside.

The exhibition’s first gallery—the one where I was meant to begin—differs from the remaining rooms in one vital way: it is the only room to contain pictures of people. These include Working class man (Andamooka opal fields) (2017), an enlarged family photograph of Scarce’s grandfather and his daughter taken on the opal fields near Woomera. And the extraordinary Dinah (2016), an enlarged photograph of Scarce’s great great grandmother Dinah Coleman, the reproduction of which is prohibited. The photographer is unknown, but the timing coincides with Norman Tindale’s visit to the Lutheran Mission at Koonibba. She is the matriarch presiding over the gallery and, indeed, the entire exhibition.

The nuclear testing zone, the laboratory, the burial ground, the coffin: these are the sites at which Scarce places her multitude of glass forms, and each encounter between the two is devastating as an allegorical tableau. That they refer to lived histories of Aboriginal Australians since colonisation makes that devastation all the more palpable, as well as incommensurable.