Works from the Okatsuka Collection; Ragnar Thomas, c. 1988: A Selection of Drawings by the Rosebud Group

⬤ Works from the Okatsuka Collection, TCB art inc. 3 Feb - 3 Mar 2024 ⬤ Ragnar Thomas, c. 1988: A Selection of Drawings by the Rosebud Group, TCB art inc. 3 Feb - 3 Mar 2024

A Munch in Brunswick. This might suggest an invitation for brunch at Walrus, lunch at Tochi Deli, or dinner followed by drinks at The Alderman, Flippy’s or wherever else. Though presently it could refer to either of two small, rather languid, paintings allegedly by Edvard Munch currently on show at TCB. In fact, I almost missed them; when I visited on a Saturday afternoon the volunteers were themselves locking up and leaving early for a late lunch. They form part of a small group of works, supposedly on loan from the Okatsuka Collection and the Hiroshima Museum of Art in Japan, put together by Miki Okatsuka and Amy Stuart. Not only are there two Munchs, but two Kazimir Malevichs (a painting and a small drawing, both from his Suprematist period), a delicate, dreamy pen portrait by Tsuguharu Foujita (the Japanese member of the School of Paris), as well as a gouache still life study from Sydney modernist, Grace Cossington Smith.

Exhibitions featuring even minor works by artists of this stature are uncommon sights in Brunswick. Is this a strange exercise in bamboozling the Japanese Embassy out of funds under the guise of soft power? It certainly would be a coup to convince the Japan Foundation to cover the costs of shipping to and installation in this tiny gallery, nestled down the end of a hallway, past the kitchen and artist studios… But where are the attendants? The video cameras? Where is the room sheet with sponsor logos loitering in the margins? Miki Okatsuka and the Okatsuka family are also missing; googling them produces nothing. Perhaps their reputation remains hidden in Kanji, beyond English language search results?

The only person involved in this show who does seem to exist is Amy Stuart. While a painter, Stuart nominally works under the guise of organiser and researcher. Her earlier exhibitions revolve around recovering the supposed forgeries of Frederick McCubbin paintings by a mysterious Japanese artist. It seems that with Works from the Okatsuka Collection, Stuart has moved from faking fakes to making outright forgeries. While the two Malevichs look like obvious copies (the small drawing looks like it was done in biro), the figurative works are quite good, if not convincing. The Foujita is uncannily precise and, in a nod towards material realism, one of the Munch’s Stuart has artificially aged the surface of so that the reclining figures are riddled by cracked, flaking paint.

Yet the fakery only seems half the point. The Cossington Smith includes a glazed Japanese vase as part of the mise en scène; the Munch portrait depicts a Japanese woman in traditional garb. Stuart’s clues point to the long-acknowledged influence of Japan on European modern art since at least the 1880s. Though this also seems to a degree incidental. Instead, the crux of the show seems to revolve around the inclusion of Cossington Smith, sticking out oddly amongst the other works that would otherwise raise little comment if presented together overseas as a collection. Cossington Smith, whose oeuvre was largely confined to depicting her home and the surrounding suburb of Turramurra, functions here as something of a proxy for the long Euro-centrism and lack of interest that marked much of the institutional engagement in Australia with Japanese art (although there is a longer and more tangled history of connections between artists and individuals).

Though in Works from the Okatsuka Collection Stuart presents this art history truism in reverse: the disengagement not represented through any admonition of Australian lack, but via the forged occidental curiosity of the Okatsukas (one might also note that both Okatsuka and Turramurra, a Gamargal word, translate roughly into English as “hill”). While Australian collections are largely absent of works by Japanese modernists, it poses the question of whether a Cossington Smith painting lives somewhere in Japan? Is there even any reason why one should? There is a playfulness to Stuart’s approach that could be stodgy if undertaken with more didactic intent. The combination of both mischievousness and painterliness puts her approach at odds with the desiccated, Vitsoe-core sit-down-and-read-these-print-outs style of archival research art recently critiqued by Claire Bishop. Indeed, the show feels like an act of historical fantasy, a daydream on the non-history of Australian and Japanese entanglement.

The historical bent continues in the other half of the gallery, with the exhibition C. 1988: a selection of drawings by the Rosebud group. Here fake works by well-known artists are swapped for real works by complete unknowns. This is a retrospective exhibition, organised by artist and writer Ragnar Thomas, of drawings produced by the amateur art group Rosebud. Active from 1983 to 1995 in Melbourne, their workshops combined Surrealist derived exercises and primarily drawing, followed by exhaustive communal psychotherapeutic discussion.

Rosebud was an initiative by therapist Sid Forsey and painter Geoff Lowe (who now resides in Paris, working collaboratively with Jaqueline Riva as A Constructed World). They conducted regular private workshops and occasional performances with a group of amateur non-artists, employing a “wide range of experimental psychotherapeutic methods to work-through their interpersonal, emotional, and professional concerns.” Rosebud did have a somewhat public presence during their existence, but this was largely through Lowe’s incorporation of motifs and images from these workshops into his widescreen, tableaux-like paintings in the 1980s. This quasi-collaboration extended to collaborative paintings directed by Lowe, most notably a series of monochromatic works (for example, the 1995 painting Minimalist Republic (with Rosebud), which appears as a rectangular block of monochromatic red reveals itself upon closer inspection as a patchwork of painted rectangles, each with its own differing brushstrokes, one per contributor).

The Rosebud drawings are an equal mix of the fantastical and grotesque, providing a stark contrast to the tasteful, measured bourgeois tone of Stuart’s modernist re-workings. They are hasty, simple drawings of banana republic generals, GI strong men, skeleton-like Japanese soldiers, plane engines, and ghostly spirits. Verging on caricature, there is a slightly vulgar, comic book-like quality bringing to mind Hergé doodles or a teenager’s scribbles . Their hasty energy provides a strange window into the on-going impact of Vietnam and the Second World War on the Australian psyche vis-à-vis the conflict in the Asia-Pacific in the 1980s.

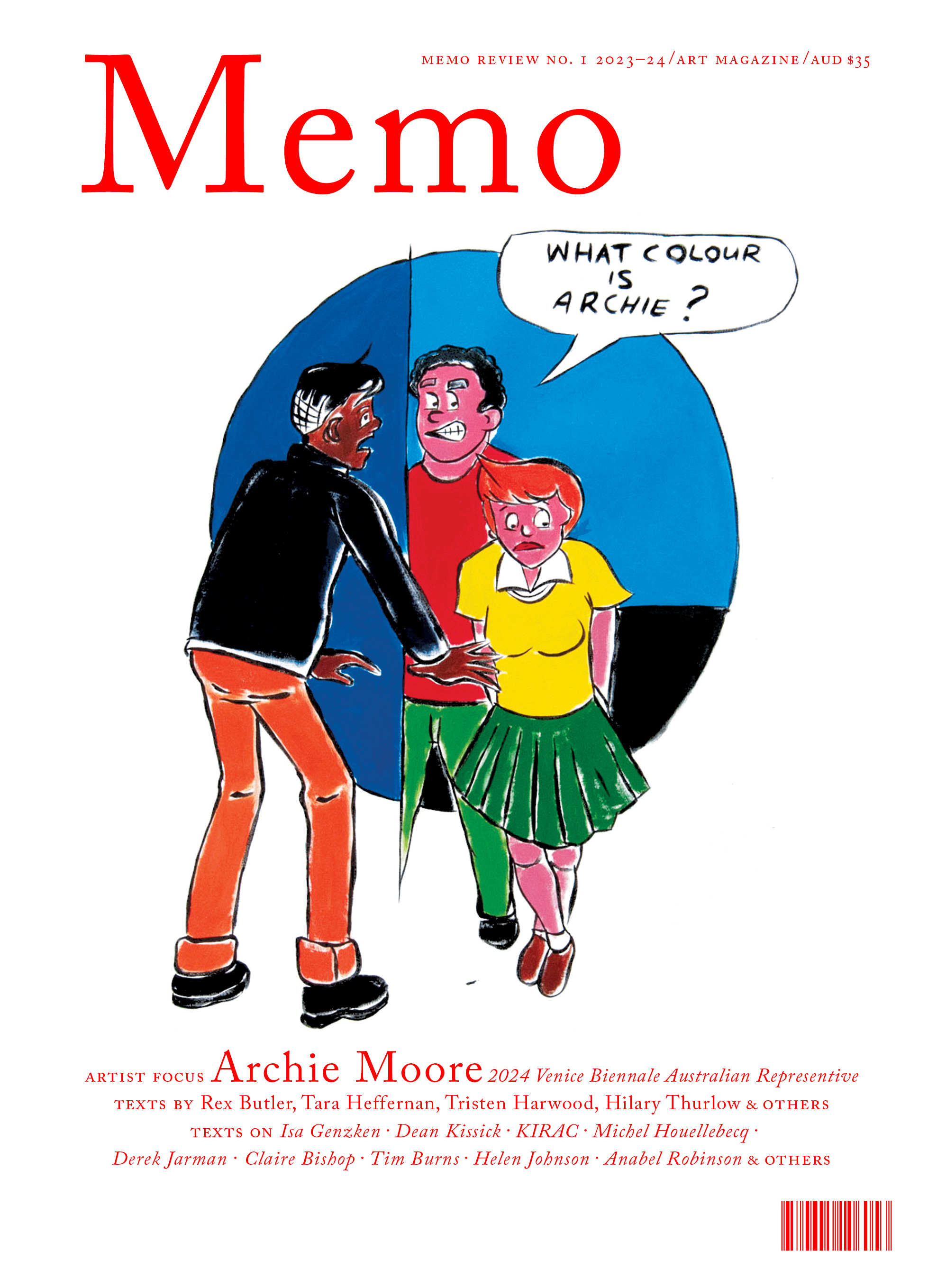

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

The most arresting work is the largest, a group re-working of André Masson’s contorted surreal-cubist Massacre works from 1930s.Masson’s maimed bodies of war are refigured into a group self-portrait of rape and murder, each participant’s individual voice disfigured and re-assembled into a nondescript mass. A group portrait of the Rosebud participants reveal a fairly harmless bunch, like primary school teachers, so the suggestion of violence in the works selected by Ragnar is surprising.

While Rosebud can be seen as part of the long hangover from the 1960s hippie moment, ultimately the mood of these particular drawings here owe something more to the lingering after-life of punk. Confrontation is hinted at in the eight rules of participation they had agreed upon, with their final rule being “no physical violence without consent.”

That this small, but highly engaging retrospective is being held at TCB is unusual. The function of a small artist-run gallery like TCB is to provide a space for non-commercial, contemporary art. Looking through their online archive spanning the last fifteen-odd years, there have been very few exhibitions with any retrospective angle. Indeed, there is no reason for DIY independent galleries to provide historically minded shows: there are simply too many contemporary artists (young and old) with limited opportunities for exhibition. There are notable exceptions; the curatorial vision of the now defunct Guzzler, contra other house galleries, digressed into historicism. Similarly, the programming at Conners Conners also has a backwards-looking inflection. Their 2023 group-show The Abduction of Ganymede was both compact and elegant in tracing the post-painterly object in Australia since the 1960s.

The inadvertent consequence though is that art-historical exploration—whether consolidation or revisionism—remains largely outsourced to major collecting institutions. If not TCB, where else could the minor history of a group like Rosebud be chronicled? Maybe in the commercial galleries, or even the hodgepodge of auction houses and high-end antique dealers that constitute our sluggish secondary market? Unlikely. Australia has very hard limits as far as the question of art history is concerned. One outlier, the Brisbane gallerist David Pestorius, recently lamented on Instagram that gallerists and art-dealers have a tendency to be conflated here. Art dealers are “essentially shop keepers selling mostly uninteresting figurative and landscape paintings”, whereas gallerists “take a position on culture.” Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of the latter and an overabundance of the former, again leaving stewardship in the hands of the institutions.

This issue similarly hovers in the background of Stuart’s show. While her project of similitude might appear as an exercise against intellectual property, some rehash of the “appropriation art” era, the re-purposing of such iconic names seems more concerned with the public domain of which the museums are the primary custodians. The Munchs and Malevichs are long past being mere property. Stuart’s borrowing of both artists’ names and styles is an art equivalent of pharmaceutical generics whose patents have long ago expired.