Paintings, like people, change over time, so it is always a fascinating exercise to unfurl canvases kept safely in storage for more than four decades and show them in a fresh light and in a different country to that in which they were conceived. Virginia Cuppaidge’s Skyspace series, from the late 1970s and early 1980s, embodies the opalescent Manhattan sky but is infused with memories of the bleached colours of the Australian landscape. Now, against the cool white of a Collingwood gallery’s walls, they acquire a retrospective aura that permits a new view, across time and place, allowing us to reflect on this short but pivotal phase of Cuppaidge’s work.

The earliest work in the exhibition, Sapphire, 1977, represents a transition from Cuppaidge’s first series painted in New York: the Geometrics. Begun in 1970, and inspired initially by Manhattan’s “looming skyscrapers on the dark avenues”, the Geometrics are large horizontal abstract compositions framed along the top and bottom with two rectangles of contrasting or unexpected colours (turquoise and yellow, maroon and blue, or—in the case of Sapphire—pale salmon and candy pink). The rectangles are tautly separated by an in-between zone, often loosely brushed in, akin to a breath or to the air between two hands held one above the other without touching. Both the large slabs of colour and the careful attention to painterly process reflect the sort of work Cuppaidge responded to at the time: Brice Marden’s minimalist canvases, Mark Rothko’s soft-edged forms and Hans Hofmann’s rigorously structured blocks of intense colour.

The Geometrics also reflect an unexpected sculptural sensibility. Colour has not only an emotional character but also a certain weight in these works; forms are balanced or juxtaposed like so many horizontal steel girders. Of course, given that Cuppaidge was living with Clement Meadmore at the time, the subject of sculpture was ever-present. She also befriended many other contemporary sculptors while working at Max Hutchinson’s gallery, Sculpture Now, at 127 Greene Street, SoHo. In such a fertile creative atmosphere it is understandable that this sculptural feeling should manifest in Cuppaidge’s painting.

Three events in 1975–76 sparked the second New York series that came to be known as the Skyspace paintings. The first was a month-long MacDowell Colony Fellowship, in the woods of New Hampshire, during which Cuppaidge produced five paintings as well as some crayon drawings of wild grass stems. In the process, she realised the importance of the space in between the grass stems—so much so that “the background surface came forward and became the sky”. This in turn prompted the desire to explore “an expanse of light opening the surface”. A Guggenheim Foundation Grant, in 1976, enabled her to follow this new direction and focus entirely on her painting for a year without the distractions of gallery work or teaching. And in the same year she purchased a SoHo loft, on the top floor of 66 Grand Street—“a narrow but entirely busy street conducting traffic from the Holland Tunnel on the west side of Manhattan to the Williamsburg Bridge”. Living in an area she describes as “grimy and noisy”, she “decided quiet and tranquil where I lived was essential”.

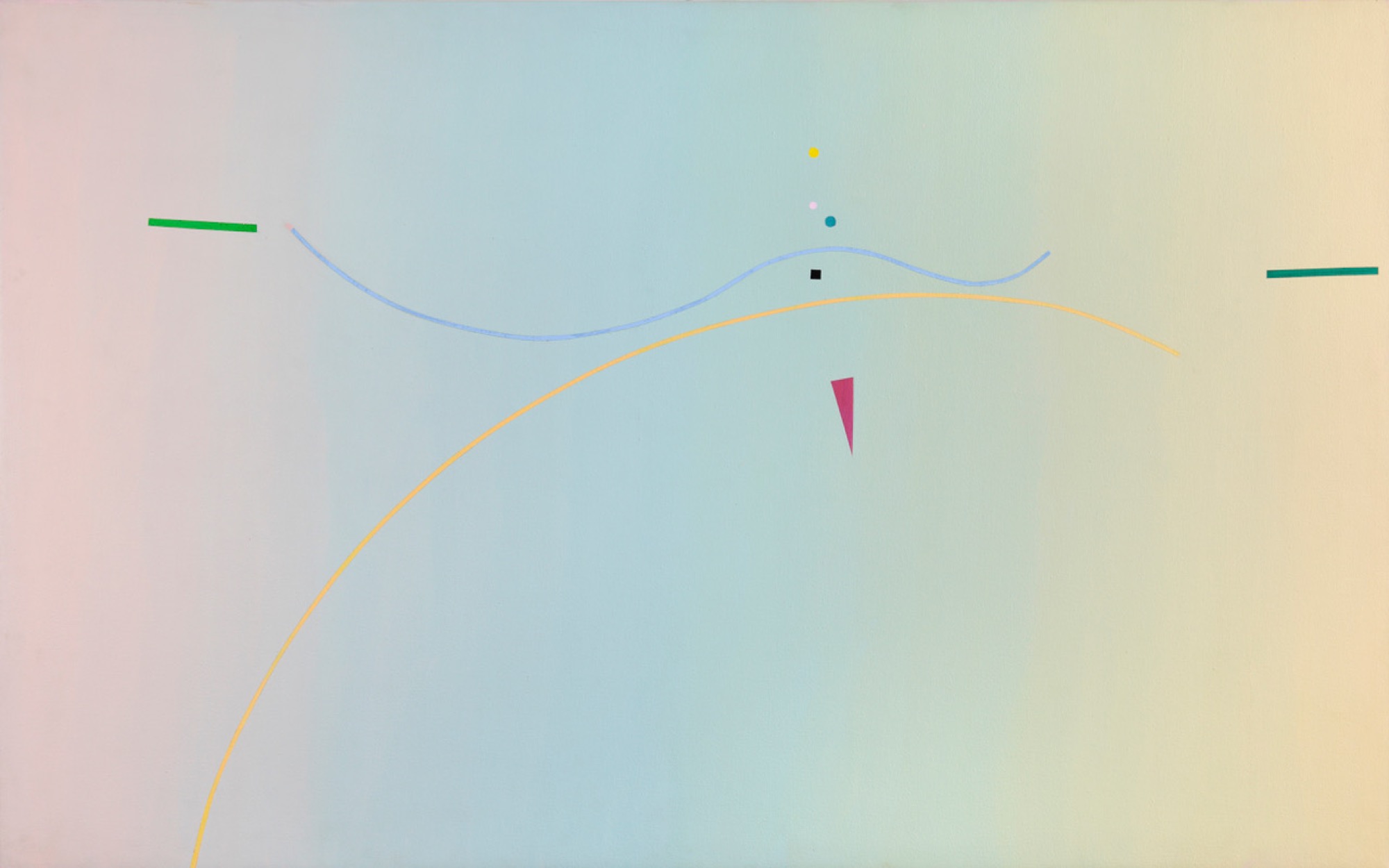

The Skyspace paintings embody these qualities of quietness and tranquility. The central zone of the Geometrics paintings has expanded to occlude the heavy rectangular bars so that the entire canvas is now airy and suffused with light. Gone too are the areas of loose brushwork; in their place are layers of smooth paint applied slowly and laboriously with a sponge, each layer allowed to fully dry before another layer of a different colour is laid over it, with anywhere up to forty layers contributing to the luminous surface. Tonally close colours are blended to create an undulating field of colour, evocative of the sky at different times of the day: whether “the dawn sky over Manhattan, with the quiet before the noise of the morning traffic on Canal Street”, as in Grand Street Dawn, or the fleeting glow of dusk, as in Darkon (Cuppaidge’s personal childhood term for sunset).

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

Juxtaposed against these fields of blended colour are delicate arcs, rods, triangles and dots of colour, painted by hand or drawn or collaged onto the canvas in black, acidic greens and vivid primaries. There is a playful, acrobatic sense in the way Cuppaidge conjures these forms with precision and calculated risk. They too evince a sculptural awareness of balance. Their painterly antecedents may lie with Miro but they also respond to the airiness of an Alexander Calder mobile or a Kenneth Snelson tensile construction, hovering and extending in space.

Their titles are personal, eclectic and sometimes romantic. Lilika is a Hawaiian word meaning “going softly”, which seems to describe the all-over softness of the undulating pastel background, punctuated by an intense small black dot. Vrinda, a feminine name, was chosen from a baby name book and means “cluster of flowers; virtue and strength”; the choice reflecting Cuppaidge’s involvement in the feminist movement in New York in the early seventies. Black, White and Beige is her riff on jazz great Duke Ellington’s three-part Black, Brown and Beige, 1943, which charted the history of African Americans (Cuppaidge saw Ellington perform on a number of occasions). It also draws attention to the notoriously difficult neutral and achromatic palette, which Cuppaidge usually advises novice painters to avoid.

Cuppaidge’s Skyspace paintings are at once emotionally charged and romantic yet as tautly balanced as steel constructions. Conceived and created in New York, and now repatriated to Australia, they represent a visionary experiment in minimalism infused with romanticism and painting steeped in sculpture.