Sidney Nolan and Narjis Mirza

Rex Butler

Sidney Nolan: Search for Paradise, currently on at Heide, begins with a magnificent suite of paintings. Towards the left corner of the long opening wall are Nolan’s Woman and Tree and Garden of Eden, both from 1941. They’re clumsy, heavy-handed, said to be influenced by Nolan seeing the work of Georges Rouault reproduced in Art in Australia earlier that year and look like works the great New Zealand painter Colin McCahon was making around the same time.

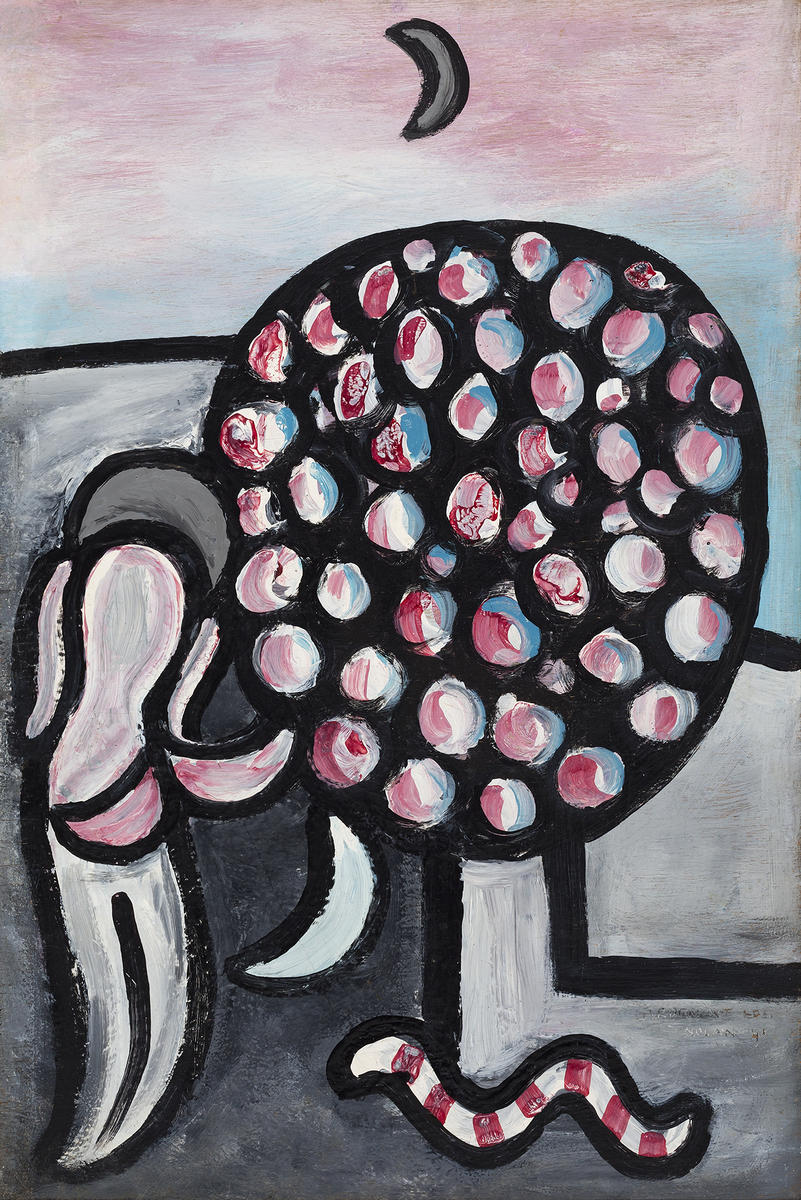

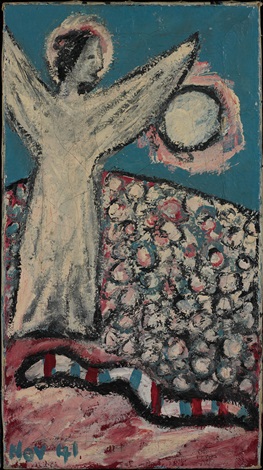

In Woman and Tree, we see Eve go towards an apple tree, with thick banded snake at the bottom, the horizon a squared-off Cézannian thing and a crescent moon high above echoed in its pale reflection down below and the smooth curves of Eve’s hair, hips and legs. In Garden of Eden, an angel stands arms raised in a field of flowers, this time against a burning sun, casting Adam and Eve out after Adam succumbed to the sweet apple that Eve offered, and he was unable to resist.

Nolan was painting a lot of similar works around this time. He was living in a menage à trois at Heide, having started an affair with his patron’s wife, Sunday Reed, while his own wife was pregnant with their daughter Amelda and their marriage was in the process of breaking down.

Jane Clarke in the catalogue for her 1987 NGV Nolan retrospective Landscapes and Legends suggests that Woman and Tree was inspired by the German poet Rainer Marian Rilke’s ‘Annunciation (Words of the Angel)’, which begins with the angel Gabriel confusedly saying such things to Mary as “I am the day, I am the dawn,/You, Lady, are the tree”, as though somehow he’s growing or cultivating her or what is inside her—and it can be supposed that Nolan is hubristically suggesting this of Sunday Reed, even though it was the Reeds who were in fact Nolan’s patrons and benefactors.

There is a whole run of these angel figures who are also lovers in Nolan’s work from around this time—Angel and Tree, Lovers, Tree and Moon, Round Tree and Figure and Tree, all from 1941—and we even have Lovers, Luna Park from the same year, in which it is hard to tell whether the two figures are young lovers lying on the grass under the arch of the Big Dipper or wingless angels waiting to be born. (And it’s certainly interesting to note—in a connection the exhibition is intelligent enough to make—that the stretched-out angels of Figure and Tree become just two years later the swimmers taking in the sun of Bathers.)

I think maybe Search for Paradise might have paused a little longer on this early period of Nolan: after all, if you’re going to argue for a fundamentally religious conception of his work or that he was haunted by the idea of a paradise lost, either personally or in terms of Australia, you need to see how this is manifested in his work. Later in the show, we return to this early moment with Nolan’s series Paradise Garden (1971), consisting of some 1320 individual studies of real and imagined wildflowers and tropical bush ferns intended to be put together in one gigantic mural, inspired by a trip he made to Australia in 1967. And many of these eventually found their way into a deluxe book of the same title funded by his then patron Lord McAlpine, which featured, opposite plates of the plants, poems of bitter recrimination directed against his lover of thirty years before Sunday Reed, graffitied over with crudely dismembered limbs in strange echo of those elegant moon-like crescents of the original Garden of Eden. “Loving in threes/Denies death’s bruise” goes one of the opened pages of the book at Heide. “Walking the great planet/Seeking original sin/Finding the right domicile/To have it in” goes another, before concluding with the extraordinarily cruel lines—Nolan was twenty-three and Reed thirty-five when they started their affair—“Steeled by a noon whisky/I enter her old plumbing”.

Maybe the big opportunity lost was to include Nolan’s Cemetery (1943) from his extraordinary Wimmera Landscape series—the one he made on the run after deserting his military post—which features an angel on a gravestone with arms stretched up towards the sky. It’s a brilliant gesture that echoes the forward-tilting horizon that at once reveals the distance usually hidden in conventional landscape painting and is a profound expression of the fantasy of the Australian landscape as an empty terra nullius.

There would undoubtedly be highlights in Nolan’s later career—the Ned Kellys, of course, the daring of the blacking-out of Eliza Fraser’s face in the Francis Bacon-like Mrs Fraser (1947)—but really the story is of him slowly losing his mojo: the polyvinyl acetate scrapings of the Leda and the Swan series (1957–), the thinly washed or glazed surfaces and high perspectives of such things as Pretty Polly Mine (1948) and Central Australia (1950), which are really just vulgarisations of the astonishing Wimmera series paintings.

Altogether the show is perhaps just a tiny bit self-referential, casting Heide as a Paradise that Nolan, having once experienced, could never get over. It was a compelling idea to divide his life up under such headings as “Heide: Garden of Eden”, “Paradise Lost”, “Wanderings”, “Search for Self” and “Paradise Garden”, but ultimately a bit reductive. There is seemingly a new Nolan retrospective on every five years—one ended just this March at TarraWarra Museum of Art dedicated to Leda and the Swan—and it’s obviously becoming harder to find new angles. Two suggestions: wouldn’t it have been good to have put him in the NGV’s Queer show, for indeed it’s quite possible that that famous menage à trois also involved a relationship between Nolan and John Reed. Second: a show about Nolan’s slow decline from the early 1950s. Undoubtedly, between the years 1939 with Moonboy and 1947 and the last of the first Kelly series, Nolan is Australia’s Picasso—the greatest Australian artist of the twentieth century—but afterwards, like Picasso, there are re-runs, self-parodies, reckless over-production. And, like Picasso—here’s the show—Nolan was aware of this: his America’s Cup paintings, his Dreaming series, the spraypainted abstracts, the endless Kellys… It’s all a self-commodification of his early genius that also makes him something like Australia’s Warhol.

There is another attempt to find Paradise currently underway in Melbourne, one that arguably is a little more generalisable and a little more consequential. It’s Narjis Mirza’s Hayakal al Noor or Bodies of Light at the Islamic Museum of Australia in Thornbury, in which letters fall like angels from the sky.

Anderson Road, Thornbury, to put it mildly, is not the leafy and landscaped Heide at Heidelberg. Just off the thunderous Moreland Road, it is home to Fire Rescue Victoria, Mark Tuckey Furniture and the rundown Merri Business Park, although to be fair just over on the other side of the road there is something called CoParadiso Mycelium Studios, which is a New-Age co-working space.

The Museum is largely a social history museum, covering such topics as Australian Muslim History, the History of Islam, a list of the great literary works inspired by Islam, a list of the Six Core Beliefs of Islam and worshippers from around the world performing Adhan or the Call to Prayer in their respective accents (in Australia it is the AFL footballer Bachar Houli, in England it is the ex-folk singer Cat Stevens). The Museum also reminds us of the Muslim contributions to mathematics, science and the fact above all that the game of chess was invented in Ancient Persia. There are works by contemporary Australian artists Zeina Iaali and Anisa Sharif and a portrait by Abdul Abdullah of journalist and broadcaster Waleed Aly, maybe the smartest guy in Australian public life, not that that would be hard.

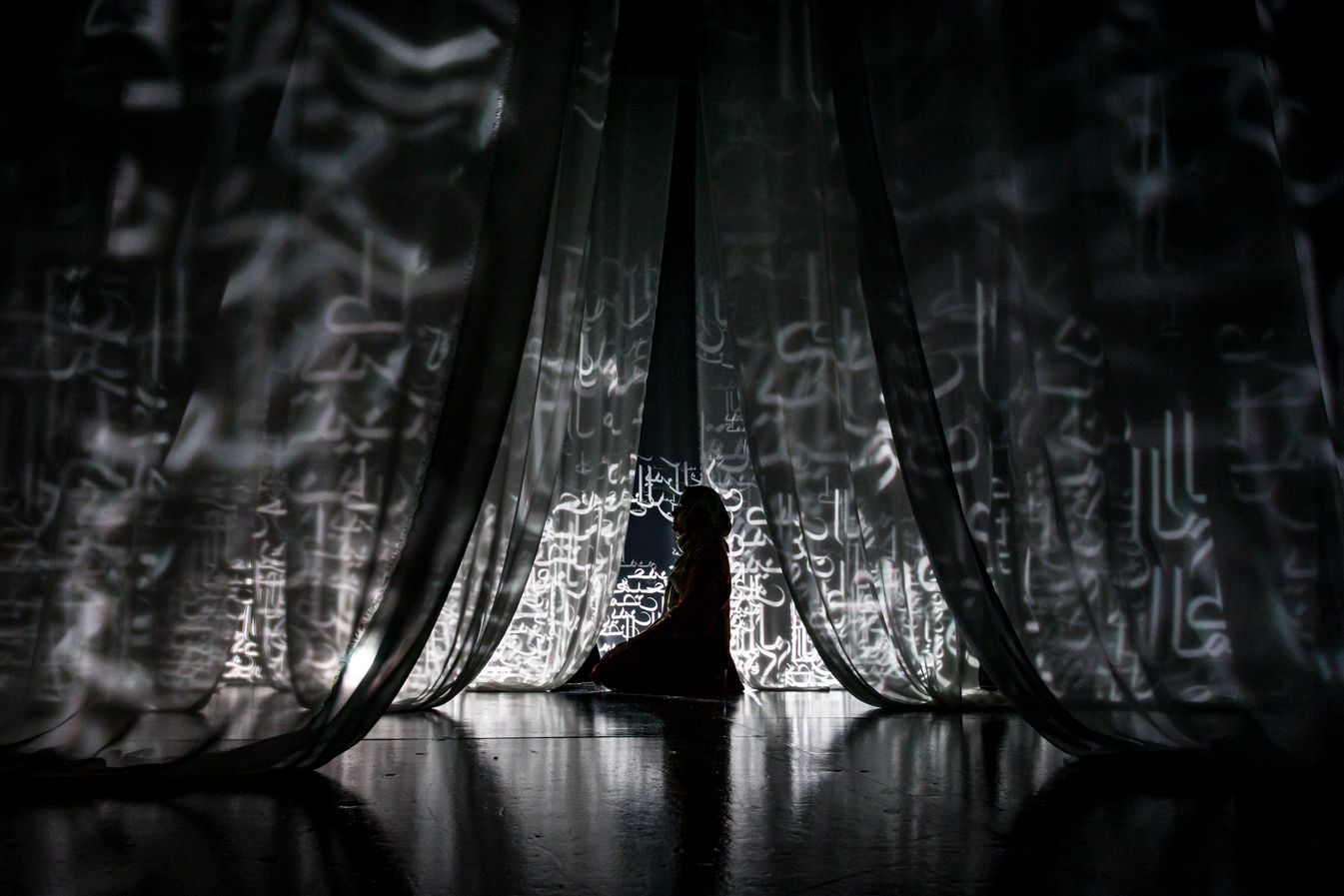

Downstairs in two smaller rooms is where the Museum has its temporary exhibitions or shows the works of art it commissions. It’s where Mirza’s Bodies of Light is playing. You walk into a dark space and a beautiful voice is singing. On a series of white chiffon curtains, hanging one behind the other, letters from the Arabic alphabet are shown floating slowly down, gathering at the bottom, cast by a projector mounted up high on the wall.

Or, actually, not simply letters. As was explained to me by my kindly tour guide, they’re properly called Muqatta’at or mysterious letters, and they’re a combination of between one and five letters that are found at the beginning of 29 out of the 114 chapters of the Koran, just after the Bismillāh or introductory phrase “In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful”, that begins each one.

The Koran was originally revealed to the prophet Muhammed by the archangel Gabriel over a period of some twenty-three years and then subsequently written down by his companions after his death (Muhammed himself was actually illiterate). But the meaning of those strange, seemingly extraneous letters at the top of a number of the chapters of the Koran has led to any number of theories about their meaning and significance, from the seventh-century Islamic scholar Abd Allah ibn Abbas thinking that they stand in for God and his attributes to the twelfth-century Fakhr al-Din al-Razi believing that they refer to the particular Surahs or chapters in the Koran they are attached to, to the nineteenth-century German Orientalist Theodor Nöldeke suggesting first that they record the names of the owners of the first Koranic copies in seventh-century Saudi Arabia and then that they gesture towards the archetypal copy of the Koran that exists only in heaven. (One of my favourite authors, Jorge Luis Borges, inspired by the material power accorded to language in Islam, named two of his stories, ‘The Aleph’ and ‘The Zahir’, after letters in the Arabic alphabet, and his great parable ‘The Library of Babel’ is about the way that through the sheer permutation of letters we could ultimately say and predict everything about our universe.)

In Mirza’s piece, only slightly less modestly, we witness the Muqatta’at or mysterious letters floating slowly down to earth, sharply focussed on the front curtain and mystically amorphous at the back. Accompanying this is the artist’s sister singing each of them as they fall through two slightly out-of-synch speakers, as though in call and response. Islam is, of course, a religion of recitation, with an emphasis on the Koran’s memorisation and correct pronunciation and its followers praying five times a day, during which time they repeat the words or verses appropriate to that particular Salat.

On a screen in the next room, the artist sits crouched as the letters are projected onto her, which turn the otherwise white letters red and yellow when they strike what she is wearing. And the same thing happens back in the main room when, after half an hour alone with the work, a group of schoolchildren enters and the projected letters fall on their uniforms. Their bodies are lit up in the darkness as they run excitedly across and behind the various layers of curtains. The previously unmoored words find their earthly reference and the spectator becomes part of the work. The work calls out to us and we answer.

On the far wall of the gallery, there is a poem by twelfth-century Spanish poet and mystic Ibn Arabi, ‘Listen O Dearly Beloved’, which is definitely more pleasant in tone than the one Nolan wrote about Sunday Reed. It is plaintive and imploring in its mode of address, supposedly spoken by an angel lamenting the fact that humans have never properly comprehended them: “Listen O deeply beloved!/I have called you so often and you have not heard Me./I have shown myself to you so often and you have not seen Me”.

But, of course, all this is written by a human adopting the persona of an angel looking down upon themselves. And maybe that’s what all our various religions are: a way of imagining what we appear like when seen from somewhere else. How small we seem, how insignificant our worries, how the only way we are visible is as a collective. It’s a bit like all of those apples in the tree or flowers in the field in Nolan, with the differences between us shrinking when seen from the perspective of an angel. Or it’s like that song we hear in Mirza in which we no longer hear the individual letters but just the beautiful melody that runs between them.

(I recently made a second visit to the Queer show, this time with some students, and noticed high up on the wall in one of the slightly more distant rooms Nolan’s Bathers (1942). The didactic even spoke of the way that Nolan “had relations with both men and women during the 1930s and 1940s”. I too must have ignored the angel above me the first time I wandered through the show. 13/4/2022)

Rex Butler teaches Art History in the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture at Monash University.