This week marks fifty years since the 1967 referendum and last week at Uluru a meeting of Indigenous leaders met to discuss a united strategy on constitutional recognition. Fifty years is a long time in anyone’s book, and with little material progress toward reconciliation, recognition, and ‘bridging the gap’, there is a widespread consensus that a symbolic mention is not enough to decolonise Australia’s founding document. The ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’, released last week by the Referendum Council, called for meaningful constitutional reform to enable First Australians to “take a rightful place in (their) own country.” The ‘Statement’ called for First Nations people to be heard through the governing idea of Makarrata, a Yolngu concept for a coming together and healing after a struggle.

At least until Makarrata is brought about, the struggle continues. Restless, currently showing at the VCA Margaret Lawrence Gallery, presents a dense and uncomfortable examination of the struggle of symbols dealing with the naturalisation of the modern Australian state. These symbols are often both literal objects as well as potent metaphors, pointing to a sense of duality within symbolic activity. In fact, like the Uluru Statement last week, there is a real tension in this show between the necessity of symbolic engagement with the past and the urgent need to act toward the future and the present.

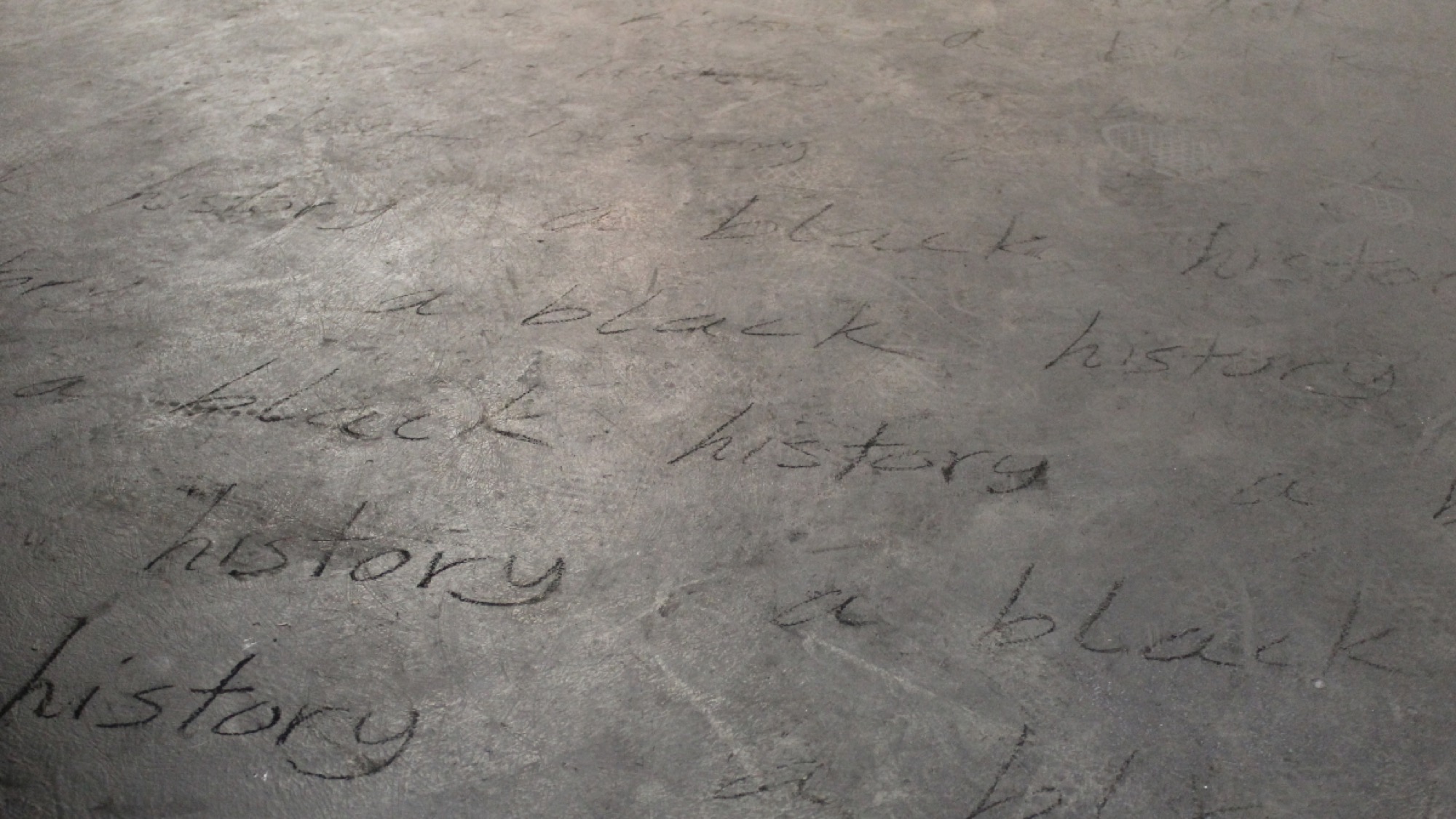

The work in Restless speaks to both these conditions. Representing or referring to an Australia both past and present, urban and rural, there is a strong examination of how Australia’s past filters through into the present, especially through its objects. The density of these explorations is palpable, as is their entanglement with the socio-economic counterparts in daily Australian life. The materials and symbols of the work seem to refer to an Australia both clearly past and eerily present: the work of Megan Evans and Karla Dickens uses objects sourced from antique stores in their assemblages, while Nick Devlin incorporates a multitude of flattened Australian two cent pieces, a now redundant currency. Jordan Marani’s work centralises an iconic Australian horror film from the 70s, a reflection on normalised frontier violence. On some walls hang Gordon Bennett’s welt paintings, while across the entirety of the black painted gallery floor Bennett’s work A Black History (1993) repeats those three words in black charcoal. The past also features in director David Sequeira’s thinking for the show, as he remembers Bennett’s 1993 show at Sutton Gallery (‘A Black History’) as a wakeup call for curatorial practice in Australia.

Karla Dickens presents a series of assemblages around the role of Indigenous women in rural settler Australia. Sexualised bull horns burst through dusty Akubra hats in Bush Cocky I, II and III (2015) alongside wire dressmaker’s dolls stripped topless down to their petticoats both feathered and cotton in The Help, and Brand – The Help (2015). These figures of ghostly women have tool belts and apron pockets full of equipment for cultural survival: spoons, branding irons, feathers and clapsticks. As if the imagery of sexual violence was not clear, Workhorse II features a worn, burnished and vulval horse’s collar or yoke into which are forcefully thrust so many cricket stumps. What makes these works so powerful is that this sexual violence is enacted through the tarnished patina of the antique store, those tan-hued archives of the last two hundred years where colonial identity is bought and sold in deceased estates. Middleclass Sundays spent in country towns evoke the urban Australian myth of the country life, and it is chilling to reflect on the Indigenous women who had to endure the subaltern position of both womanhood and Indigeneity.

The floor-based assemblages of Megan Evans also draw from the material colonial archive. Two antique upholstered chairs drip with red-beaded blood flow, while the jaws of a taxidermied fox drip with the same flow of red in Fox (2015). Alongside, Hero (2015) features a glass-encased model ship sailing through the same red glass beads. Evans’ stark and direct imagery underlies the problem of trying to account for violent dispossession and genocide in anything but the most direct symbolism: the long drip of blood falling through the Fox’s teeth seems a tad operatic as a metaphor, until you realise that it isn’t a metaphor at all but a kind of re-enactment or illustration.

Likewise, Nick Devlin’s work speaks a language alternating between metaphoric and literal. His black-soaked Australian flags in Black Flag (2013) suggest the modernist monochrome, or at least Rauschenberg’s flags, but at the same time they are literally Australian flags. Sovereign (2017) also adorns the blackened flag with flattened two-cent pieces, in a quite beautiful defacement of retired currency. What was once literal ‘value’ becomes decorative and formal. Along with We Are Golden (2017), a seemingly unaltered golden space blanket, Devlin’s work speaks to the growing inadequacy of the symbols of value we use to account for Australian identity.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

In the second room, Jordan Marani’s work is a single horse trailer, or float, central on the floor. Painted white, it has the blue chequered pattern from a police van under the blue word ‘policy’. Walking up into the trailer, a small screen waits at the top playing the 1970s classic Australian horror film Wake in Fright (1971). It’s a scary film, the violence under the mask of mateship and ‘buying each other a round at the pub’ also strongly recalls characters from the past (or perhaps this is just me: having grown up in rural Tasmania, this film gives me a shudder of recognition). With all the appearance of an official, although slightly battered, police horse trailer, White Horse Trailer Policy (2017) makes a connection between the mounted police and the drover mentality, where we climb into the back of the horse’s paddy wagon, our paddy wagon, and the horse is trained to recognise its masters in the film. On the wall are a collection of small decorative abstract paintings featuring the word ‘NO’. While Marani’s work often features geometric investigations into various four-letter words, the ‘no’ in this work is strong and firm rather than flippant: the paintings are as so many voices standing together in protest against the ‘white horse ‘of policy set against it.

The works of Gordon Bennett unite the show, mainly through the power of the floor text. ‘A black history’ is erased as contemporary art is consumed, remarks Sequeira, and Restless beautifully displays this. It is an aporia or bind that haunts so forcefully any time colonial Australia—and those who benefit from it—tries to naturalise its privilege. Bennett’s ‘welt’ paintings are so described because the artist fused a thick vinyl paint with a slash of red, producing the effect of a cut to the skin before it heals. Symbolic and literal, the welt seems to mark a passage of time from wounded to healed. A passage through memory, where to be healed is to be unable to forget the truth. For too long has this country been able to forget. Does this mean Australia needs to render Bennett’s text permanent, on all floors and stages, symbolically as well as literally, as Makarrata suggests? Restless is a reminder that until this is at the very least legislated, any sense of calm is an act of forgetting.

David is a PhD Candidate in Art History and Theory at Monash University.

Title image: Gordon Bennett, A Black History, 1993 (recreated 2017), photo: D.Wlazlo.)