That the Mornington Peninsula now boasts three privately endowed sculpture parks is a remarkable fact given the relatively small geographic area. Joining the long-standing McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park (founded and chiefly supported – up until recently – by the late Dame Elisabeth Murdoch) are two new additions, both attached to wineries: Montalto in Red Hill South and Point Leo Estate at Merricks. However, where Montalto remains something of a commercial enterprise, with many of the works for sale and few senior artists included, Point Leo Estate bears many of the hallmarks of Pauline and John Gandel’s philanthropic benevolence. This is a sculpture park that combines the personal predilections of collectors, and the private collector’s preference for works by established artists, with public largesse – albeit at the price of a $10 entry ticket.

Having heard whispered tales for some years now of breath-taking real estate and extravagant sculpture commissions (a couple of which I had the fortune to preview in the fabrication stage at Fasham’s), I entered Point Leo Estate with high expectations. These were confirmed – at least initially – at the entrance by the iconic presence of the late Inge King’s Grand Arch, a black-painted steel work first conceived in 1983 and enlarged three times previously at a scale of 1:3 (in 1983), 1:2 (in 1988) and 1:15 (in 2001) – this last version sitting permanently outside the Art Gallery of Ballarat. This most recent – and, in all probability, final – enlargement, commissioned by the Gandels in 2011 at a scale of nearly 1:20, is perfectly positioned on a stone round-a-about, allowing visitors to admire the sculpture’s undulating flanks while they circle in their cars. The entry walls of the estate’s flagship restaurant and cellar door seem to cradle King’s work, echoing and accentuating its formal curves. While the decision to enlarge a work that was already in the public domain may have disappointed the artist, it is clear that Point Leo’s architects responded positively to the work, mitigating the Tarrawarra-like concrete bunker effect of the main building.

Like Tarrawarra, one side of the Point Leo sculpture park borders vineyards, which lends a European sense of order and agricultural bounty. But the mainstay attraction here is the ocean view to the south, looking over Bass Straight. Point Leo Estate opened in October 2017, so is still very much in its infancy. The landscape retains much of the feeling of recently converted paddocks, with groves of eucalypt saplings sitting at odds with the longer established spruce windbreaks. Beds of low-growing natives are struggling to gain a foothold in this exposed and somewhat arid site, and only a strip of lawn circling the main building has been irrigated – resulting in a green circle surrounded by the inevitable brown swathes of desiccated grass that are the curse of Australian sculpture parks.

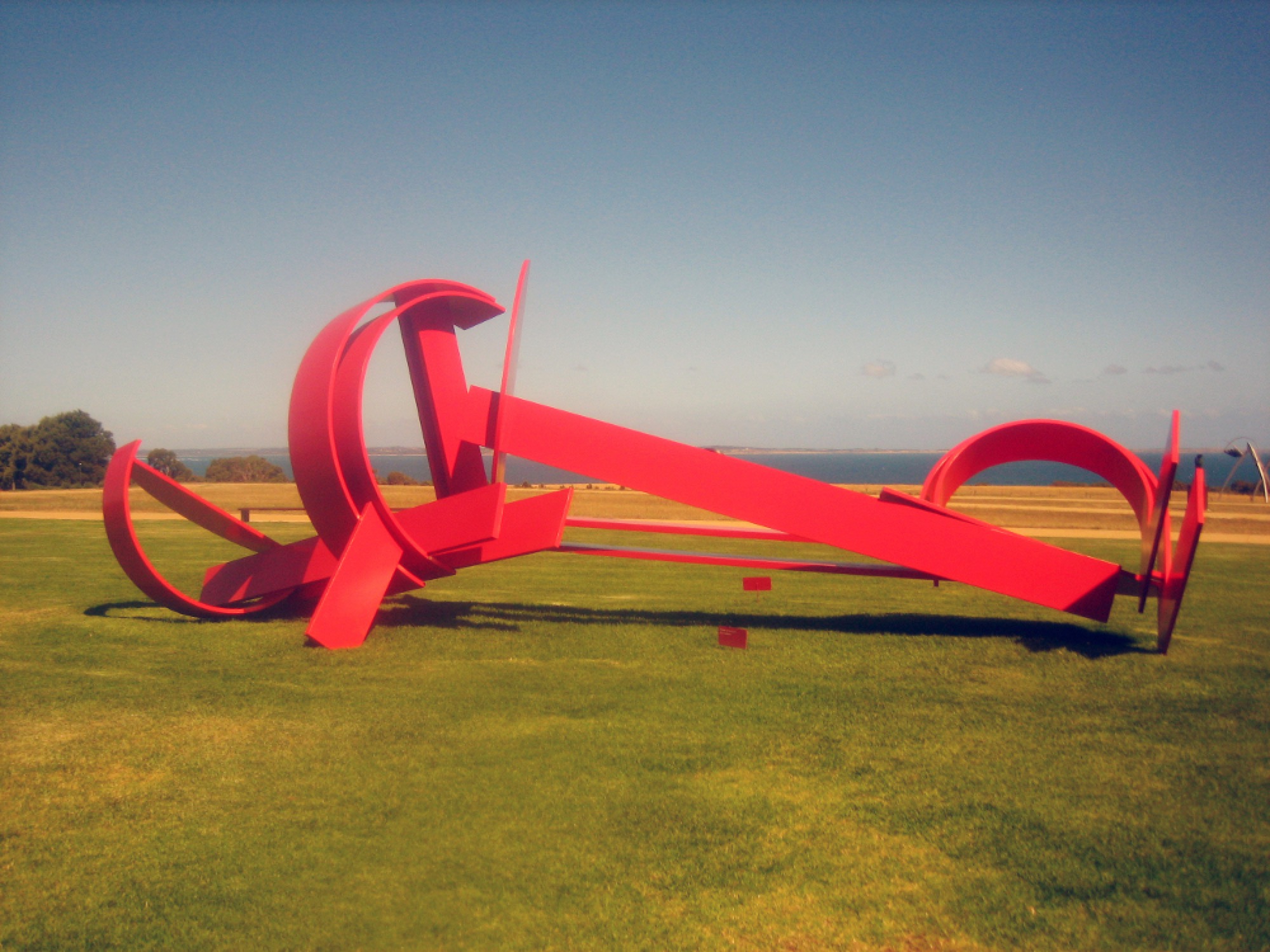

Allowing for early teething problems, there are a number of discordant notes. Why the excessive signage? Surely the instructions at the entrance to not touch the sculptures were sufficient? The additional red plaques instructing us not to touch, placed mere centimetres from the more valuable works, were superfluous. They intruded, for instance, on Clement Meadmore’s Riff, 1996, seen from the gravelled path with unbroken views of Western Port in the distance. Other signage seemed arbitrary. A large black and white sign beside the purpose-built lake that houses Adrian Mauriks’ Impulse, 2011, forbidding swimming in the lake or the throwing of stones, might just as well have censored naked cavorting in the grass.

A more serious issue is the installation of certain works. Anthony Pryor’s

Horizons is crippled with concrete boots – its foundations protruding above ground, cancelling the effect of airy expanse that the work’s prime position near the sea should have augmented. Lenton Parr’s Plant Forms, 1960, which many may recall in its earlier location outside Myer at Chadstone Shopping Centre, is cramped for space, surrounded by a number of smaller works that intrude fussily in a way that the parked cars and shop windows of Chadstone strangely never did. One of these works was – when I visited some months ago – a pair of Akio Makigawa stainless steel seedpod-like objects, which, a sign informed, were on temporary loan from the artist’s estate and would soon be replaced by the Gandel’s work that was then on loan to the NGV. While this had the pleasing effect of underscoring the significance of the work in the Gandel’s collection and quietly pointed to the Gandel’s philanthropic connections with the gallery, and overlooking the unfortunate typographic error that puts Makigawa’s death at 1974 rather than 1999, it seems incredible that the pair of works should be sited barely a metre from Parr’s Plant Forms. The crowding did a disservice to both works.

Scale is also occasionally an issue. Greg Johns’ To the Centre, 2000, is perfectly scaled up to a size just large enough to accommodate a view of sea and sky. I suspect the artist had a large part to play in choosing the appropriate scale. Conversely, Lenton’s Parr’s Vega seems overblown. First made in 1969 (a fact unmentioned on the plaque), this was originally 84 cm long. It is now over ten times that size, fabricated in 2012 – eleven years after the artist’s death. While Parr realised a number of similarly scaled works in his lifetime, these were designed with such a scale in mind. His 1960s works almost never exceeded 3 metres at their longest dimension. Vega would have been just as effective at a scale of 1:3, similar to the impressive Rigel, 1968, in the Queensland Art Gallery collection. Other works, such as Andrew Rogers’ Rise 1, 2010, are dwarfed in the open setting and seem unnecessarily decorative.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

As the above list of names suggests, the Point Leo Estate collection is strong on dead white male artists (Meadmore, Parr, Pryor, Peter Blizzard, Herbert Flugelman, Robert Klippel and Oliffe Richmond, to name a handful) and their living contemporaries (Geoffrey Bartlett, Gus Dall’Ava, Ron Robertson-Swann and so on). I noted the inclusion of only three women: Inge King, Jane Valentine and Deborah Halpern, whose whimsical Portal To Another Time, 2005, in her trademark medium of ceramic mosaic strikes an appositely carnival note on the restaurant terrace. The international selection seemed a little random, if interesting, though perhaps Matt Calvert’s comically brutal Night Imp, 2010, amused me more than Dean Bowen’s Lady with Flowers, 2011, simply owing to its novelty.. Sympathy towards artists who have lived or studied in Israel is evident. Engagement with artists from Southeast Asia, South America or Africa is equally absent. However, this is a private collection made public; it has no obligation to aspire to universal representation. Suffice to note the collection’s characteristics.

Aside from the demographics of the sculptors represented, it should be noted that most works might best be described as monumental late modernism. Preference is given to works in the durable mediums of steel and bronze; there is nothing of wood, and only one work incorporating stone (Blizzard’s Ancient Range Floating, 2003) to any significant degree. Those seeking something more ecologically attuned, such as the ephemeral and site-specific work that characterised advanced sculpture in the 1970s, or the more process-oriented work of recent times, should look elsewhere.

With all of the aforesaid misgivings, please make no mistake: a visit to the Point Leo Estate sculpture park is well worth the drive down from Melbourne. One hopes that the issues regarding signage will be rectified in time, that those works which are currently over-crowded will be granted greater breathing room, and that those others which are currently marooned on concrete footings will be permitted to sink a little and settle into their new surroundings. Perhaps they might do away with signage altogether as the excellent free Point Leo Estate App makes it largely redundant. Just as the landscape will surely soften given time, the sculpture park as a whole will doubtless gain with maturity. It is certainly a valuable addition to the peninsula and a noteworthy venture in the annals of art philanthropy in Australia.

Jane Eckett is a sessional lecturer in art history at Melbourne University.