O’Keeffe, Preston, Cossington-Smith: Making Modernism

⬤ Heide Museum of Modern Art 12 Mar - 19 Feb 2017

Two things are glaringly obvious in just the title of Heide’s Summer exhibition O’Keeffe, Preston, Cossington Smith: Making Modernism. The first, of course, is the apparent refusal of the hegemonic history of modernism: that the pivotal period in art history was shaped by a bunch of dudes. The second is that the curators have attempted to render redundant the cultural cringe of the so-called provincialism that Australian art has long been said to suffer from. Georgia O’Keeffe—the “mother” of American modernism—placed on equal playing ground as two not-as-internationally-recognised Australian artists, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith.

In the context of Heide—a place made famous by its stable of male artists: Vassilieff, Tucker, Nolan, Perceval, Boyd—it is salutary to see an emphasis upon a female modernism. Indeed, some of Heide’s most successful female focuses have been contemporary—Louise Bourgeois in 2012, Fiona Hall in 2013, Esther Stewart in 2016. With the historical narratives of Blackman, Nolan and Tucker continuing to be the biggest draw cards for the institution (while female Heide original Joy Hester tends to be ignored), it is not surprising that the museum continues to rely upon this white patriarchal model to propel it into the 21st century—cue current exhibitions of Nolan’s slates and a Charles Blackman survey, Making History (an even greater claim than Making Modernism).

Shifting focus to the show itself, there was a similar model at play. A large dose of the familiar paved the way for small quantities of surprising, lesser known works. Entering the first gallery space, a single O’Keeffe was hung dramatically on a central partition wall. This wall almost neatly separated the works of Preston on one side of the gallery from those of Cossington Smith on the other. Even if, in theory, the exhibition was to be a survey of the three women on equal ground, the hang indicated otherwise. One would have been forgiven for reading this arrangement as setting up a hierarchy where the hero was flanked by her minions.

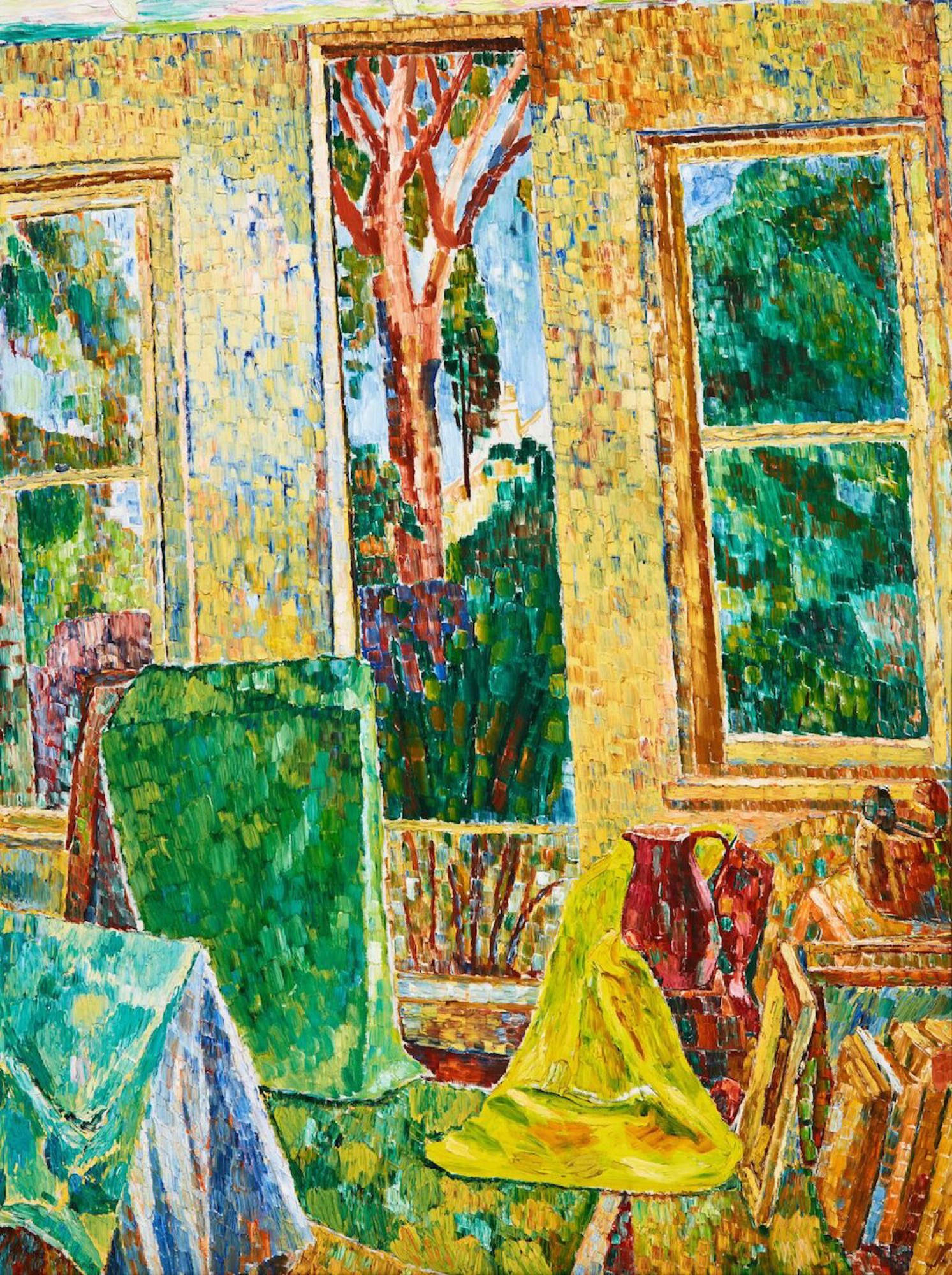

On a more formal level, selected Cossington Smiths were impressive. The pseudo-Neo-Impressionist style that has become synonymous with the painter was even more spectacular in the flesh. Classics such as The Bridge in Building (1929) were featured as a crowd pleaser but were, nonetheless, the more successful of her works displayed. Reminiscent of the utopian and technology-driven content of the Russian Constructivists, this work has maintained its bizarre otherworldliness into the present. Certainly, The Bridge in Building along with Yarralumla (1932) and The Lacquer Room (1936) demonstrated an eerie quality by virtue of Cossington Smith’s strategic placement of orange and red hues, as well as her rendering of flat planes. They were also stronger than later works such as Bush at Evening (1947), which features typical “Australiana” motifs painted in the rougher form of her classic stippling. Having studied in Europe for so many years, it is tempting to say that her style was greatly influenced by her training abroad. However, the danger of such a narrative is a diminution of the capacity of Australian artists to produce non-Eurocentric works of quality.

The bridge in building, 1929

oil on pulpboard

75 x 53 cm

National Gallery of Australia

Gift of Ellen Waugh 2005

© Estate of Grace Cossington Smith

In contrast, the selection of Margaret Preston works was fine but demonstrated an exploration of form that was either simply pretty or (in retrospect) ethically questionable. Indeed, Preston’s works demonstrated the awkward early twentieth-century desire for an ‘Australian’ aesthetic nonetheless steeped in a post-colonial European aesthetic. For instance, Implement Blue (1927)—an arrangement of cups and a jug on a tray—was typical of the artist’s exploration of still lifes in combination with modern techniques, especially the thick black line. The Brown Pot (1940) was a typical example of Preston’s “engagement” with Aboriginal art. In the media release for the exhibition, the curators stated that Preston produced a number of landscapes “influenced by the colours and motifs of Aboriginal art,” and that she “promoted the study and conservation of Indigenous rock art.” Indeed, this statement felt facile: a very neutral take on a topic that many would today label cultural appropriation. It also begs the question, why have three white women been chosen to represent the “untold” story of modernism?

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

oil

on canvas

53.6 x 45.8 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia

Gift of the Art Gallery of South Australia

Foundation, 1981

© Margaret Rose Preston Estate

In the large, rear gallery, O’Keeffe was given centre stage. Amongst the crowd-pleasing enlarged blossom paintings were some surprisingly atypical works, including Church Steeple (1930), featuring a palette of heavier, shadowed block colours—think de Chirico—that stood in contrast to the lighter and more diffuse aesthetic of the better-known flower paintings. Indeed, Petunia No. 2 (1924) seemed useful only insofar as it acted as a yardstick for the intriguing aesthetic developments that appeared in her work after she began spending time in New Mexico in 1929. The chronological hang of the exhibition was most successful in the O’Keeffe section, where an obvious stylistic progression over a number of decades could be seen and, certainly, appreciated.

Modernism

Installation view, 2016

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

Photograph: Christian Capurro

A colleague of mine noted that a connection between the three artists—aside from the fact that they were all women—was difficult to observe at first sight. Indeed, Making Modernism could have been three discrete shows. However, while such obvious and dramatic refusals of the hegemonic historical narrative are all too often deemed tokenistic, discounting them is simply irresponsible in the current political environment. In any case, it is difficult to measure the success of such methods: damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Amelia Winata is a writer from Melbourne