Mithu Sen, mOTHERTONGUE

⬤ Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) 22 Apr - 18 Jun 2023

Mithu Sen is a New Dehli-based conceptual artist. She works in painting, drawing, and text, but also video and various forms of new technology. She has had solo exhibitions at the Chemould Prescott Road gallery in Mumbai in 2010 and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2016 and has been included in the Dhaka Art Summit in Bangladesh in 2014 and the Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane in 2018. At the moment she has a huge solo exhibition at the Australian Centre of Contemporary Art, which entirely fills its vast hangar-like spaces, showing a wide range of her practice from the late 1990s until earlier this year.

But you will probably have to scrap all that and start again because one of Sen’s characteristic artistic devices, almost an obsession, is the putting of the prefix “un” in front of things. The show opens with an “unacknowledgement” of country and closes in almost something of an artist’s signature with a suite of drawings called unMYthU: unkind(s) (2018), and in between there is a work called, of all things, How to Unmake a Paper Boat (2019).

If the artist could, one suspects, she’d cross herself out, disappear, vanish—and, indeed, lots of the work in the show, like the performance piece How to be a SUCKcessful Artist (2019), in which she lets forth a stream of gibberish, or Museum Piece—(un)drawing (2018), in which she frames twenty drawings from 1997 to 2017 and sticks them like books on a broken shelf so that they can’t be seen, make themselves as incomprehensible and inaccessible as possible.

But in crossing herself out, Sen also wants to do away with or subject to critique all the forces that made her. In the opening room of the show, she has a piece entitled Be Beyond Being (2021), which is a recorded Zoom meeting of eight hopefully not unwitting post-colonial scholars, in which she at once challenges the idea of a “post-colonial” India—”post-colonialism is a by-product of colonialism”—and mocks the academic discipline of post-colonial studies, which we can be sure shaped her in various ways—“post-colonialism never happened.”

Equally, in the first room of the second half of the show, Sen, after the largely video- and text-based work of the first half, exhibits beautiful hand-made metal castings of a series of body parts—arms, legs, breasts, torsos—suspended by a string from the ceiling and casting a shadow against the wall bathed in bright light. But, in the didactic for another work in the same room—in a nice piece of curating—Sen is quoted speaking of the way her work represents a kind of “unlynching” with regard to the violence that plagued the newly independent and religiously divided India, and those previously benign and seemingly weightless objects take on a whole new gravity: the leg has perhaps been severed, likewise the arm, and God forbid the breast.

A lot of Sen’s work is like this. For all of its nonsensical babble and parodic academese, it’s didactic and polemical. She’s engaged in many of the usual art-world discussion points: personal identity, the ongoing effects of colonialism, and even the future of the human race. (One of the hashtags she signs the show off on is #unhuman, and presciently she even has a proto-chatbot called Alexa to answer stupidly such questions as “What is the meaning of xenophobia?” and “What is the meaning of right-wing?”)

But then, in a kind of turning upon itself or another one of the “uns,” in the second half of the show Sen changes tack or tone and her work is much more recognisably “art”-like. Sure, in the first of its rooms we have those small metal sculptures, “unlynchings,” but they are still rather beautiful. However, in the next, we have what Sen calls—of course—a Museum of unBelongings (2023), a huge revolving Wunderkammer containing hundreds of found and collected objects. They appear to be the archetypes or even clichés of various non-European cultures. We have Javanese masks, Japanese Noh dolls, blackface statues, even kangaroos and boomerangs, along with watchbands eyeglasses, squeezed-out tubes of paint and plastic skeletons.

Yes, there’s a kind of “critique” going on here, an attempt to liberate these objects from their cultural origins or at least to unsettle the stereotyping effect they have upon the cultures from which they are said to derive. The new Museum of Unbelonging in this sense might be seeking to break with the inevitable “nationalism” of most museum collections, with their artefacts or works of art made to testify to the inherent character of the people who created them. But for all of this, many of the objects, as they slowly move towards us, evoke intimate personal memories. They are the kinds of things that we have grown up with and helped give us an identity: snowglobes from our family holidays, chatter teeth from our childhood pranks and Kodak film to record our fugitive memories. We feel like reaching out and touching them, or putting coins in a slot so that we might grab one with a crane, like those plastic boxes full of furry animals that used to be found in amusement arcades.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

Coming after this, it’s in the last room of the show where we see most fully the artist’s “hand” in a series of large watercolours on paper, and on the final wall an extraordinarily frank—and extraordinarily sensitive—depiction of two men making love, which asks in its caption “Are they conjoined twins?”, only to answer “No, they are gay lovers.”

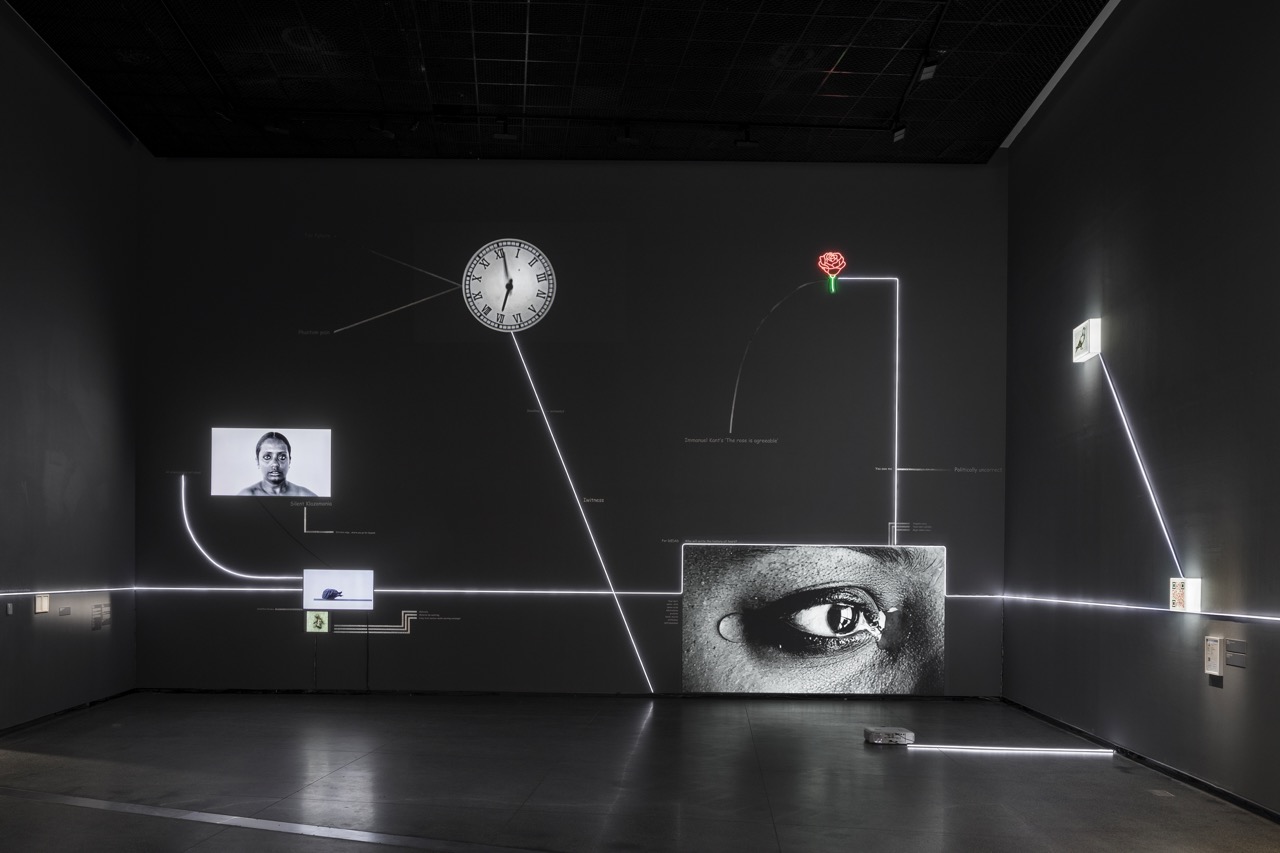

It is a dramatic shift from the negation and emptying-out of the first half of the show — installed in just one enormous anonymous space — to the succession of progressively more intimate rooms of the second half. Perhaps the turning point comes at the end of that first space where facing us on the far wall as we walk into the exhibition — and next to a series of graffiti-like text works saying such things as “I AM POLITCALLY INCORRECT,” “I/RONIC/U,” “IS NOT AN ABORIGINAL LAND” and, excuse us, “I CUNT IMAGINE”—there is a beautiful fluorescent light work of a red rose along with the text “Immanuel Kant’s ‘The rose is agreeable,’” a slowed-down video of the artist’s eye emitting a tear and a just-born bird seemingly coming alive as it is eaten by ants in a sped-up video.

“The rose is agreeable” is, of course, Kant’s ruling out of simple bodily pleasure as a valid aesthetic emotion: it is not “critical” enough, not “self-reflexive” enough, and thus we go down the whole disillusioning thrust of first modernism and then post-modernism and all of those “uns” Sen throws at us. But what is the matter with the “agreeability” of the rose, we might ask, in the new era of “feeling” in art? It’s another “un” maybe, but it’s the negation of the “un” of Kantian aesthetics and its aftermath.

Sen’s art is divided, torn, confused, unresolved—and that’s what makes it interesting. How well ACCA sees this or grapples with it in its opening art-world gibberish introductory panel is another question. “The exhibition is presented as an illuminated mind map,” we read before we enter the gallery: “In the visual, linguistic and performative multiverse of Mithu Sen’s practice, her artistic gestures are offered with the promise of radical hospitality in ‘an attempt to bring in the complex, the marginalised and the invisible across quantum spaces and multiple realities.’” In some ways, that’s exactly the kind of thing Sen parodies as soon as you step inside in her lectures and videos. (Watch her deliver an artist’s talk on her work for Contemporary Art Week at the Guggenheim in 2016: it almost makes as little sense as the average art-history lecture at university.)

Sen’s work absolutely captures the dilemma of the contemporary artist and everybody involved in the art world today: you have to play the game while knowing it’s nonsense, and the more you say it’s nonsense the more the artworld will love you for it. Is Sen playing the game or saying it’s nonsense? Does she belong or does she stand outside? Both maybe. mOTHERTONGUE.