Mike Parr: Sunset Claws, Part 3: Going Home

⬤ Anna Schwartz Gallery 5 Dec - 16 Dec 2023

The Work

Three weeks ago, on Saturday 2 December 2023, artist Mike Parr staged a live performance at Anna Schwartz Gallery. The third of a three-part exhibition titled Sunset Claws, the Going Home performance was open to all members of the public, with video documentation subsequently presented in the gallery.

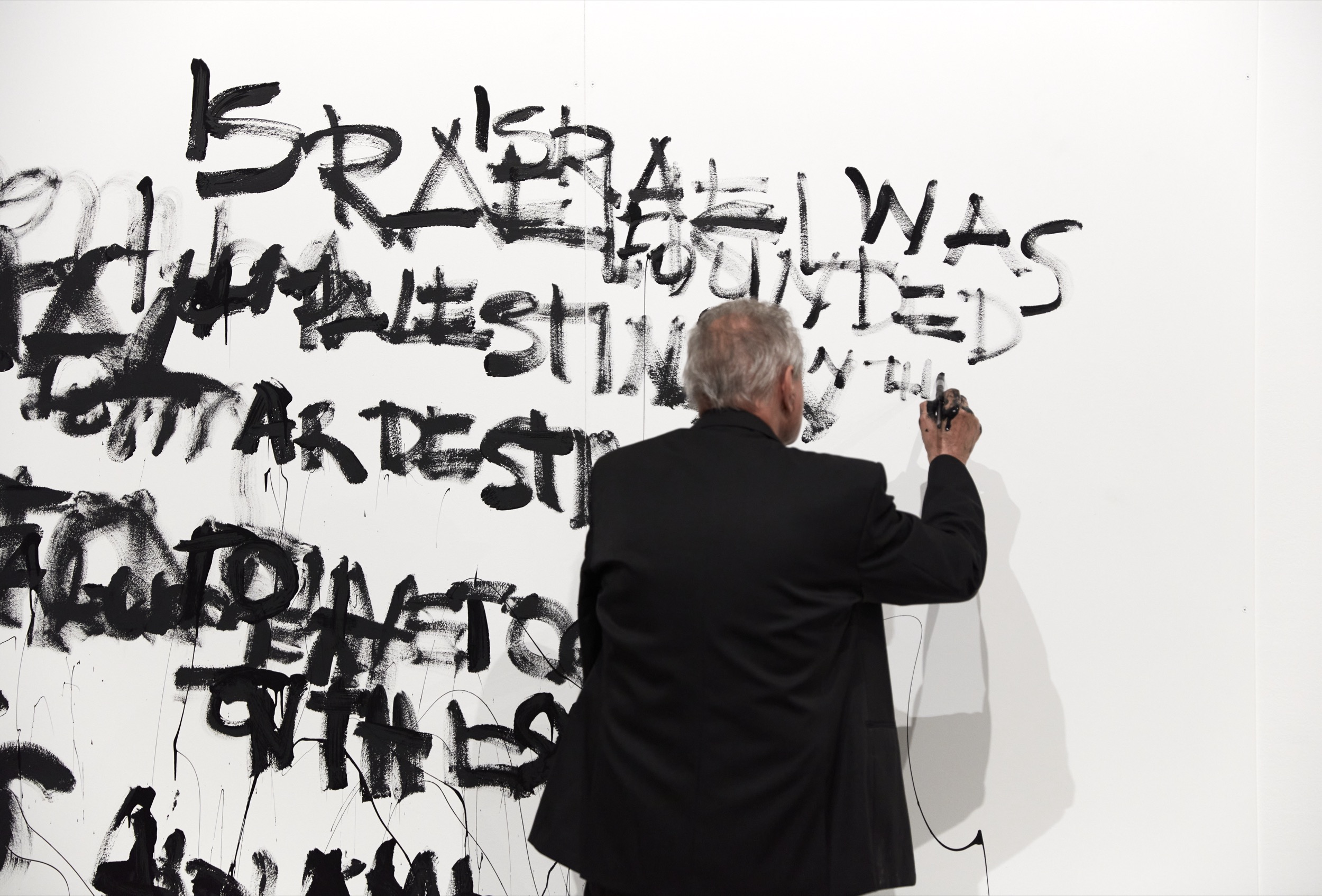

During the five-hour-long performance, Parr executed three distinct actions: painting words on the white walls, painting over the words in red with a sponge, and painting three upside-down horses in black, all with his eyes closed.

In the first action, Parr drew on thirty-one statements sourced for the most part from the London Review of Books (LRB) as well as his own record of two sentences said to be based on comments spoken to him by his gallerist Anna Schwartz, related to the Israel–Gaza conflict. He did not just copy each statement onto the wall. Instead, a co-performer (a gallery employee) read them out to Parr one by one. In the video documentation, the co-performer’s voice is deep and has an unvarying pitch, creating a hypnotic, almost meditative effect, punctuated by the artist climbing up and down a ladder and inscribing each statement on the wall.

The statements varied in length, complexity, and subject. “What is clear is a decoy,” read one. Clad in a black business suit, Parr would then proceed to paint the phrase on the wall with one of three paint brushes tucked under his missing left arm. “You cannot dream the unconscious away. Jacqueline Rose,” read another. Like the unconscious, Parr’s palimpsest-like technique of layering text made his writing inchoate, messy, and hard to read. Other statements were overtly political: “Israel was founded on the forced displacement of Palestinian people.” When longer statements were read out, Parr seemed to retain and paint only parts of what had been said.

Like many artists of his generation, Parr is as interested in meaning and language themselves as much as he is in any specific content. This interest stems from a deeper concern with psychoanalysis and the unconscious. In fact, Parr’s “cut up” approach to found statements goes back to his earliest output, like his “word situation” works and “found poems,” some shown at Inhibodress gallery, which he formed in the early 1970s with artists Peter Kennedy and Tim Johnson. In the Going Home performance, language decays and distorts as it passes through the performer. The work in this sense bears some relation to Parr’s work The Emetics (Primary Vomit); I Am Sick of Art (Red, Yellow and Blue) (1977), where he consumed acrylic paint and regurgitated the colours onto a canvas.

Parr ended the first stage of the performance by writing onto the wall, “the monochrome is a coverup.” He then proceeded to cover the text in red paint, producing three large red monochrome paintings down the length of the gallery’s long east-facing wall. For anyone familiar with Parr’s “Blind Paintings” series, this is a reference to the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich’s monochrome Black Square (1915)—or rather the Red Square variant of the same year—a painting that also had its origin in a performance of sorts as the stage curtain to the 1913 Futurist opera Victory over the Sun.

For Parr, the significance of the monochromatic black square is in its function as a stage curtain, which, like the psyche, covers up something else behind it. In his essay Becoming Revolutionary: On Kazimir Malevich, Boris Groys interprets Black Square as an acceptance of the revolutionary destruction of existing society (it was painted during World War I, in which forty million people died), marking the end of cultural nostalgia and sentimental attachment to past culture, which it covers over. Parr has described Black Square as “the null of the image.”

It would be too easy to read Parr’s monochrome cover-up as a statement merely about censorship or an allusion to Anna Schwartz Gallery, known for representing key Melbourne minimalist artists. It is after all Parr himself who covers over the statements he has drawn from his own readings and conversations about the current violence in Gaza and Israel.

Parr, with his eyes closed and an assistant reading the prepared list of statements to him, doubled his separation from his subject matter, as if he wrote in a self-imposed trance-like state. If he begins with a confrontation with his own subjectivity and identity, he develops it into a mystical language. By doing so Parr is as much turning into himself and away from the pervasive image culture that has defined the global reception of a regional Middle East conflict as he is also turning away from himself—and toward an unknown power, which he makes himself a medium of.

But by invoking the shaman, Parr also invoked the charlatan, as was the case for others in his line of performance art, like Joseph Beuys. Parr proselytises in self-seriousness about his practice as if to disciples: “I came in blind, and I left blind. I will never see the outcome of any aspect of that performance.” A poignant moment was captured in the video, showing him resting and seemingly squinting through his eyes to observe his work, the viewer briefly catching a glimpse of the artist as if “cheating” by peeking through his blindness, seeing for an instant the magician’s feint.

The Saturday Paper editor Erik Jensen, invited by Parr, played in this sense a unique role as a witness to the performance, even having a dedicated chair with his name. Jensen, who reported to Parr that he found himself in tears at the end of the performance, was Parr’s chosen believer, expected to give testimony to the deeds of the artist in his altered state. Parr’s decision to include Jensen as a co-performer also implicated Schwartz Media and by extension Morry Schwartz explicitly in the work, as though Parr, who is deliberately dressed in a business suit costume, made himself the shadow of both.

Parr’s journey to the interior is exemplified by his paintings of a falling horse. The upside-down horse motif drew inspiration from a childhood ceramic horse. It recalls other iconic falling horses, such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Turin Horse.” According to the well-known anecdote, in January 1889 Nietzsche witnessed a horse being whipped by its owner in the Piazza Carlo Alberto in Turin, Italy. Affected by this sight, Nietzsche reportedly ran to the horse, threw his arms around its neck to protect it, and then collapsed to the ground, entering his late phase of madness before his untimely death.

Parr’s upturned horse figures suggest both infantilisation and death, which together signal a return to a kind of primal or original state. After the performance, the panels with the horse figures were removed from the east-facing wall, flipped upside-down, and then reinstalled on the west-facing wall. This transformed the gallery space into a kind of fire-lit, cave-like installation. In fact, the inchoate horse motif itself was reminiscent of the famous horses and aurochs that adorn the walls of the Lascaux cave, the site of the so-called “dawn of art” according to its Surrealist mythographers. In the final installation, the red horse panels face three opposing “white squares” in the empty wall space they no longer occupy. And so, like Malevich’s black square, Parr frames the work as a new beginning as much as he does an end to what he has covered over.

A particular aspect of the show that puzzled many was a seemingly random print hung on the far wall of the gallery featuring a quote about being half Indian titled Who’s an Indian? (2003). The quote was perceived by some as a personal statement by Parr about divided identity and an idealised spiritual community of co-existence, in contrast to the “found text” of the political material. In this context, Parr’s horse perhaps more potently recalls the German painter Georg Baselitz’s Zwei Pferde auf der Wiesse (1987), which itself seems to reflect the inverted mirror image, an iconic trope of the split subject both in the work of Jacques Lacan and in post-colonial writings on the nature of the colonial subject.

Between the actions, Parr either left the gallery or rested. Rather than strident political activism, the overall feeling was of a remorseful and uncertain moral wandering. He appeared extremely fatigued after completing the red paint, feeling the walls to navigate to the next section. His demeanour was sombre, tinged with grief. At points, his face appeared to be streaked with tears.

The Response

The morning after, at 6:53 am, Anna Schwartz sent Parr a short email indicating that her gallery could no longer represent his work. Soon after, the gallery’s homepage simply declared, “Anna Schwartz Gallery no longer represents Mike Parr.” This triggered nearly two weeks of debate, alongside a public row between Schwartz and Parr, which only seems to have subsided with a final statement delivered by Parr on 15 December.

The work translated poorly to the declarative and didactic spaces of social and mainstream media, where it quickly kicked up a storm. Parr was celebrated across social media as a pro-Palestine activist artist. Shared prominently was a cropped photograph of one section of text work, in which the words “Israel” and “apartheid” were legible. Others were more sceptical, questioning Parr’s self-centred performativity or criticising what was called “tepid” content. These responses escalated to a staged pro-Palestine demonstration live-streamed from inside the gallery, as well as graffiti on the exterior walls of Schwartz’s gallery. A prominent Jewish collector of Parr’s work was also reported to be reconsidering whether to hold on to his collection.

Articles were published in the Guardian, the ABC, The Age, Sydney Morning Herald, and elsewhere, and interviews with both Schwartz and Parr were broadcast on Radio National. Schwartz was quoted in a Guardian article saying that she was “sickened by the hate graffiti” and that “this is the only time an artist has breached my principles of anti-racism.” (There were likely other reasons at play because it is improbable that Schwartz would allow true hate speech and racism to remain in her gallery.) Parr was quoted as saying that “Anna understands very well the political nature of my performances.” “All my performances are controversial,” he said elsewhere, “they divide the audience … but that is the point of performance art.”

Despite ending her relationship with Parr, Schwartz allowed the work to remain on display and open to the public, as if she felt it was to art itself and not the artist that she owed her paramount duty. By doing so, Schwartz remained true to a brand known for positioning itself at the cutting-edge of contemporary art. She also distinguished herself from institutions like MONA, which in 2021, following pushback from social media, cancelled their invitation of controversial Spanish artist Santiago Sierra to participate in Dark Mofo, in which he proposed to present a Union Jack flag soaked in the blood of First Nations peoples from colonised territories. At the time, Parr was publicly critical of MONA.

This is not to say that Parr hasn’t faced attempts at censorship before. He faced resistance from some members of the local Palawa community in response to his work Towards a Black Square (2019), in which he buried himself beneath the black tarmac of a Hobart street as a statement about the Black War. Heather Sculthorpe, chief executive of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, was reported in the New York Times calling his work an “insult.” In 2012, he was prevented from performing a work at the Kunsthalle Wien in which he would read passages from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf in a segment he titled Bedtime Stories. One could also point to another of Parr’s protest works, on display for the duration of Going Home in the upstairs gallery, Close the Concentration Camps (2002) in Montage in Space & Time (1971–2016), in which Parr excruciatingly self-censors by having his own lips sewed shut.

Issue No. 1

Grab a copy of Memo’s first glossy annual magazine issue, featuring an extended artist focus on Archie Moore, the 2024 Venice Biennale Australian Representative, with essays by Rex Butler, Tara Heffernan, Tristen Harwood, and Hilary Thurlow.

Issue 1 features articles by Audrey Schmidt, Philip Brophy, Helen Hughes, The Manhattan Art Review’s Sean Tatol, Cameron Hurst, Chelsea Hopper, among your favourite regular Memo contributors. There are reviews and articles, including on Melbourne design art, French literature’s ageing enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, Derek Jarman’s Blue (1993), the celebrated Spike magazine cultural critic, Dean Kissick, the local cult-favourite Jas H. Duke, and much, much more.

Memo Magazine, 256 pages, 16 x 25 cm

The discussion of censorship, however, misses a deeper point. Parr wrote of Schwartz’s decision to end the relationship as completing his “liberation from the role of artist.” And there are too many clues to ignore from Parr about old people and their retirement. The choice to present a thirty-seven-year retrospective presentation and the evolving nature of the series provoked curiosity and speculation about the intent behind the titles Going Home and Sunset Claws (a sunset clause is a provision in a contract that specifies an automatic expiration date), its timing, and whether it was a calculated move by Parr. At one point during the performance, the sound of Swedish rock band Europe’s hit “The Final Countdown” bled from the upstairs gallery into the performance downstairs.

If it is not easy to read Schwartz’s choice to continue displaying Parr’s work as censorship, the perception that she might be retaliating against his politically charged actions could discourage other artists from exploring similar topics. Such chilling effects have been widely discussed in recent months, especially in relation to the situation in Germany, whose memory culture has deep sensitivity to discussion concerning Israel. The artist Candice Breitz, for example, who is represented by Schwartz (and remains so) recently had a show cancelled in Germany due to statements she made in relation to Gaza. “The climate in Germany at present is such that many Germans feel absolutely justified in violently condemning Jewish positions that are not consistent with their own in their zeal to confirm their own dedication to antisemitic principles,” Breitz, who is Jewish, is reported as saying. One could also reference last year’s documenta fifteen or Masha Gessen, whose prestigious Hannah Arendt prize ceremony was cancelled following publication of an essay for The New Yorker that drew controversial parallels between Gaza and the Warsaw ghetto. (Arendt for that matter would also be a soft target for cancellation in today’s climate.)

One observes in this dynamic a weird cultural mirroring of the patterns of the conflict itself, as if all connect—social media, art, performance, protest, culture wars, and real wars—in the same hyperreal space psychoanalysis calls the “imaginary.”

The Iron Wall of Culture War

Avi Shlaim, a British-Israeli of Iraqi Jewish descent, argues in The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World that Israel’s strategy of building an unassailable military force that he calls the “Iron Wall” (after Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s 1923 essay) to secure its state amidst Arab opposition was originally conceived as a temporary strategic means to an advantageous peace settlement. However, in the following decades, Shlaim argues the iron wall became a self-perpetuating policy reinforcing permanent hostilities, serving the interests of those who advocate for a Greater Israel. Recently, Slavoj Žižek suggested in a widely criticised talk at the Frankfurt Book Fair that a political goal of Hamas’s October 7 terrorist attack was to undermine the recent Arab–Israeli normalisation of relations by promoting the continuation of permanent hostilities with a greater goal of eliminating the state of Israel.

The iron wall in the cultural setting implies the solidification of permanent hostilities within the sphere of culture. Voices in support of Palestine are silenced or marginalised by those possessing a cultural power that could be seen as analogous to the military strength and deterrence strategy Shlaim describes. On the flip side, a cultural resistance movement finds its own targets, legitimate or illegitimate, and sustains an environment of permanent hostilities.

In such an environment, every action to silence or counter-silence is not just a reflection of ideological stances perceived to advance specific political goals, but, losing sight of the real conflict, creates its own intractable alias conflicts, sustaining cultural warfare within local communities. An acute shadow psychosis triggers everything from aggressive suppression of any content even remotely platforming Palestinian perspectives, displays of ignorance or insensitivity, targeting of Jewish individuals and communities, to outright anti-Semitism. The cultural sphere becomes a battleground divided by friend–enemy distinctions among cultural practitioners who share almost everything in common. The art world, which often claims to challenge, critique, and propose alternative narratives, instead becomes a mirror of the conflict and its official polarised narratives, replicating its dynamics and divisions in the form of culture war.

Parr no doubt sought in Going Home a passageway out of this dynamic of the iron wall and its “deadly binaries,” to borrow from Jacqueline Rose, who also refers to what Edward Said called “detached and uncommunicating separate suffering.” One could even say that for all the ambiguity and apparent open-endedness, Parr’s work was an effort to both expose and simultaneously veil the isolated and non-communicative aspects of this suffering.

It would be a mistake, however, to consider Going Home as activist art. This much was demonstrated in the work’s jarring contrast with a small group of activists protesting in the gallery, who held up a “free Palestine” banner and read out a statement before switching on a tinny UE Boom and briefly chanting “free free Palestine.” In fact, we could perhaps extend this point to all Parr’s work, in which his activism is only a layer of a deeper, introspective and intersubjective psycho-narcissism.

This accounts for the work’s doubly subjective nature, at once an outward display of symbolic self-staging by Parr and an apparently direct subjective address: it was as if the work was made specifically for Anna—as though it was to her that the work was ultimately addressed. Parr said that he chose to include two statements from Schwartz alongside the LRB statements to “poison the balance of everything else.” It is unlikely he underestimated the significance of this mode of direct address.

Schwartz for her part, citing an unidentified artist she represents, said quite poignantly in her Radio National interview that it was as though Parr wrote the words on her body. She is from a Holocaust family and referred to being triggered by the incoherent conjunction of the words “Israel” and “Nazi” on the walls of her gallery, and her perception that Hamas violence was placed into the framework of conjecture. She cites an article in The New Yorker that documents sexual and gender violence committed by Hamas terrorists, reported in graphic detail by the BBC. “I can’t work with an artist who has chosen to hurt me,” she said.

Normally, one would not dismiss the reported trauma of others. Parr replied in his RN interview that Schwartz’s oversensitivity was “hysterical” and “overwhelmed by her subjectivity.” “Anna has seen those words ‘Nazi’ and ‘Israel’ and authored her own response,” he said. “The stridency of her narcissism effectively disappeared my performance.”

Performance artists have often integrated the traumatic experiences of war into their art, placing themselves at the narcissistic centre of their work. This can be seen in the work of artists like Marina Abramović, Joseph Beuys, and the Vienna Actionist Arnulf Rainer, who influenced Parr. The strength of these performance artists is precisely this expansive narcissism which gives them the uninhibited self-confidence to go where no other is prepared to, even as they seem blinded to the pain of others. They subject their bodies and others’ social psyches to intense pressures, breaking taboos, engaging in myth making, connecting with spirits, or inducing altered states of consciousness. Performance art is in this way as much masochistic as it is sadistic.

Performance art’s acts of self and social harm are usually presented as a form of catharsis and ultimately as a pathway to liberation. In her book, Which as You Know Means Violence, Philippa Snow relates the harming and healing features of performance art to the turn-of-the-millennium American reality TV series Jackass. This series, known for its wild stunts and pranks, was described by Uncas Blythe as “a shamanic displacement of 9/11 war trauma onto what looked to the untrained rationalist eye like idiot clowns, but who in fact were voodoo medics for the whole of American culture.”

But if Parr accused Schwartz of obliterating the complexity of his work, he too descended into such obliteration as he sought to publicly defend it, declaring himself a supporter of the right of the state of Israel to exist and equally concerned with the question of co-existence. The “intergenerational trauma” of Palestinians, he said, “is storing up ongoing hostility on their part towards Israel.” Parr also objected to what he described as Schwartz’s idealised infantilisation of protesters as “just young people virtue signalling.” But in doing so he reproduced his own counter-idealisation of young artists at Gertrude Contemporary feeling threatened by Schwartz’s role on its board (the gallerist recently stepped down from the advisory role), as if he imagines they needed the defensive performativity of an established late-career artist.

Parr and Schwartz thus collapsed back into the mediatisation and useless bothsidesism that Going Home otherwise declaimed against, transfiguring the work’s public reception into a quarrel between two titans of Australian art. The two act like belligerents across the cultural iron wall, together steamrolling questions of inter-subjectivity, suffering, and co-existence in the public collapse of their long and fruitful relationship, seemingly ending, like performance art, in self-harm.

This perspective highlights the broader implications of geopolitical conflicts on cultural expression and personal relationships. It shows how atrocities perpetrated overseas impact human relationships among diasporas. None of this should be news in a settler-colonial state like ours. We live in a post-conflict society whose traditions of art have always had a complex and unresolved relationship to war and reconciliation, as if these are its lifeblood.

Part of this tradition, Mike Parr’s Going Home at Anna Schwartz Gallery did not exist in the shadow of the prevailing culture war so much as it cast its own shadow over it. We might even say that in the end it is the work that passes judgement on both Parr and Schwartz—just as it might pass judgement on all of us.